All of Federico da Montefeltro in one exhibition. Gubbio's exhibition for the 600th anniversary

When one thinks of Federico da Montefeltro, it comes naturally to associate the figure of this condottiere and patron with the great palace that stands out against the skyline of the capital of his duchy, Urbino, the main center of his power, the seat of his court, and the pole of attraction for many of the greatest artists and men of letters of the time. Never, however, did Federico neglect Gubbio, the second city of his state and the place of his birth: as soon as he was appointed duke, in August 1444, Frederick immediately visited Gubbio to sign an agreement with the municipality, on the basis of which the people of Gubbio obtained the right to continue to keep the seats of their magistracies in the palaces of the Consuls and the Podestà, while the young sovereign would continue to use, at the community’s expense, as his official residence, the palace in which his family used to stay during his sojourns in the city. What was at the time the “Palatium Vetus,” an ancient building near the Cathedral, was evidently to suffice the needs of a young lord, whose power was nonetheless constantly and steadily expanding. Then, in 1461, when his very young and beloved wife Battista Sforza visited Gubbio with him for the first time, perhaps Federico began to manifest the idea of endowing himself with a more suitable residence: a need that was deemed imperative when, in the early 1470s, visits to Rome at the court of Pope Sixtus IV became more frequent and the importance of Gubbio grew considerably. It was probably in this turn of the year that Federico decided to rearrange that complex near the cathedral to transform it into the only Renaissance palace present in a city with a totally medieval urban fabric: the task was entrusted to Francesco di Giorgio Martini, and the work, which had probably already begun in the late 1460s, experienced a decisive acceleration from the summer of 1474, but would not be completed until shortly after Federico’s death in 1482, when the duchy passed to his son Guidobaldo.

Thus was born the Ducal Palace of Gubbio, which on the six-hundredth anniversary of Federico’s birth becomes the centerpiece of the major exhibition that his hometown dedicates to him: Federico da Montefeltro and Gubbio. Lì è tucto el core nostro et tucta l’anima nostra. The phrase that the curators of the exhibition (Francesco Paolo Di Teodoro with Lucia Bertolini, Patrizia Castelli and Fulvio Cervini) chose to construct the title of the exhibition, and which is taken from a letter sent by Federico to the gonfalonier and consuls of Gubbio in 1446, is therefore not a formula of circumstance dictated by diplomatic duties. Federico da Montefeltro really cared about Gubbio, so much so that it took on the appearance of a second capital: quieter than Urbino, it was nonetheless a vital center, endowed with its own artistic culture that the duke knew how to keep alive, a meeting place that Federico chose with some frequency (and where the Urbino court, the curators of the exhibition write in their introduction, could “move to and stay enjoying the same privileges and ’comforts’ as Urbino, but far from the political and cultural turmoil”). The Ducal Palace in Gubbio itself was built almost in the image and likeness of the one in Urbino, complete with a Studiolo decorated with wooden inlays.

The secentenary exhibition is divided into three venues. The center of the exhibition is at the Ducal Palace: here, the biography of Federico da Montefeltro is explored in depth, his relationship with Gubbio is evoked, the building events of the palace are retraced in broad strokes, the Renaissance painting of Gubbio is familiarized with, and there are also two surprising sections devoted to applied arts and music. At the Palazzo dei Consoli, on the other hand, one enters into the merits of the duke’s vast culture, which gives one a way to understand his choices and better appreciate the extent of his patronage, and also touches on the figure of Frederick the condottiere, set in the context of the wars of the 15th century: the two themes are closely related, because for the mentality of the time an excellent condottiere could not fail to have an adequate literary education. Finally, at the Diocesan Museum the focus is on Federico da Montefeltro’s spirituality declined, however, according to his astrological interests. Dozens of works are on display, including paintings, books, documents, armor, furnishings, coins and more.

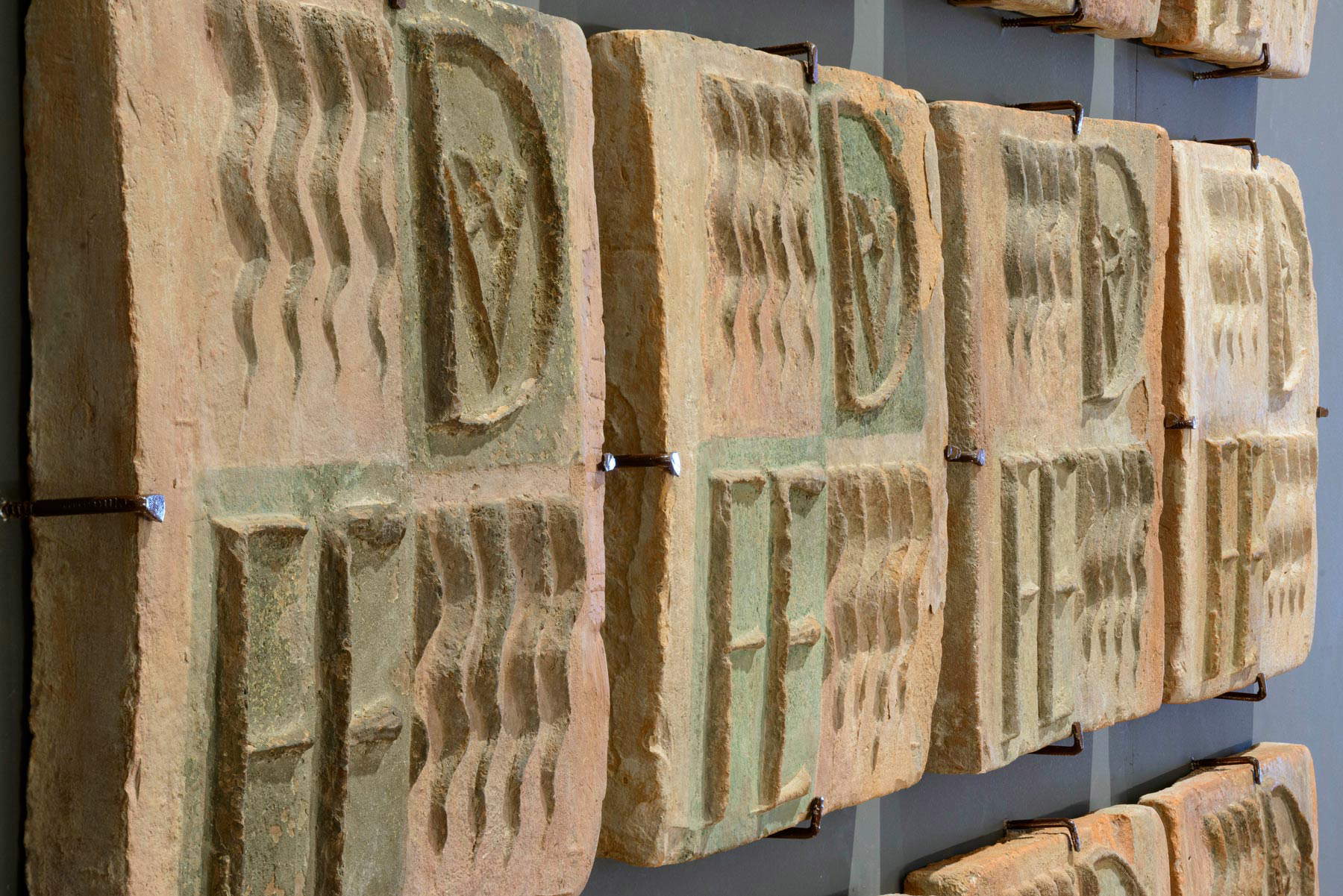

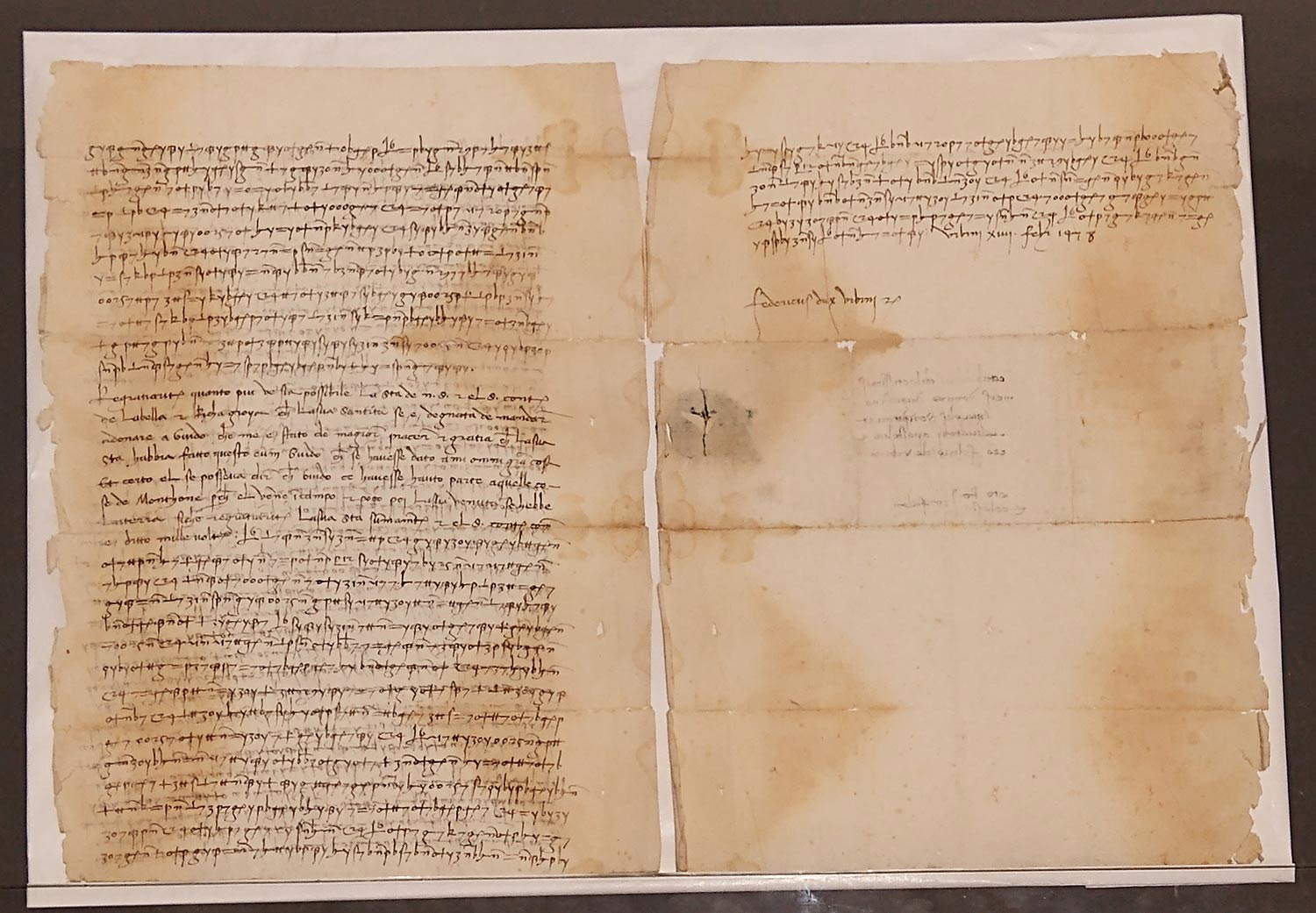

However, welcoming the public to the Ducal Palace, where the tour itinerary ideally begins, is a contemporary work, a reinterpretation of the diptych of the dukes of Montefeltro created by Fabio Galeotti: the work, titled Witnesses of Time, a 4K video projected on two LCD screens framed like the Uffizi’s double portrait, places Federico and Battista facing each other, caught in the passage of a day from dawn to night, as they look at each other and admire the landscape of their lands. È the enthralling welcome that the Ducal Palace of Gubbio offers its visitors, a mixture of ancient and contemporary that works and that gives us back the image of a duke at once distant and close, towards whom one disposes oneself with a certain deference, with the awareness that the rooms now open to the entire public were once places of power accessible to a few, and where the presence of the duke hovered everywhere, as we are reminded, at the opening of the itinerary, by the wall filled with tiles with the Frederician insignia, decorated with the famous relief “FE.DUX” traceable to the inspiration of Francesco di Girogio Martini, fired in the kilns of the Floris family in Gubbio, and originally colored. The first section of the Ducal Palace itinerary is exquisitely biographical: a showcase filled with medals, executed by the greatest medallists of the time (count, to name but a few, the great Pisanello, Matteo de’ Pasti, Pietro Torrigiani, Gianfrancesco Enzola, Sperandio di Bartolomeo Savelli da Mantova, and the more obscure Clemente da Urbino, Pietro da Fano, and Adriano di Giovanni de’ Maestri) and arriving from a vast plethora of museums, plunge the visitor into Quattrocento Italy: portraits of sovereigns and leading members of the great ruling families, from the Gonzagas to the Sforzas, the popes to the Malatestas, the Bentivoglios to the Medicis, and the Montefeltros themselves, follow one another, all to compose a kind of grand fresco of the context in which Federico da Montefeltro lived, amid power relationships and alliances, friendships and enmities (among the various documents, an encrypted letter proving Federico da Montefeltro’s involvement in the Pazzi conspiracy is also on display). Gubbio itself was an important center of goldsmith production and for a long time was also the seat of the main mint of the duchy of Urbino: one of the most relevant aspects of the exhibition is the continuous network of references to the Feltresque Gubbio.

One room is entirely devoted to the sculpted portraits of Federico da Montefeltro: Standing out in particular are the sculpted portraits of Federico and Battista (the former in marble, the latter in Cesana stone) that came on loan from the Civic Museums of Pesaro, where the dukes are depicted in profile and facing each other as in the Uffizi diptych that is thus ideally recalled, and then again the medallions with the official portraits of Federico and his natural brother Ottaviano Ubaldini della Carda, in ancient times in the church of San Francesco in Mercatello sul Metauro, another important center of the duchy of Urbino, and the lunette in which the duke is portrayed together with Ottaviano. The exhibition focuses little on the figure of Octavian, a prominent figure of the Feltresque court although resigned and therefore little known to most, and on whom, even in recent years, several studies have flourished: A humanist, lover of the arts and letters (in the lunette he is in fact depicted with a book and an olive branch to indicate his passions, as opposed to his brother who is instead accompanied by a helmet and standard), he was primarily responsible for setting up the library of the Ducal Palace of Urbino (where the lunette was probably originally placed), and as such he chose codices and manuscripts, took care of the layout, and maintained contacts with humanists and men of letters. To evoke this cultural climate, a number of codices are displayed not far away, including one of the only three vernacular manuscripts that have passed down to us Piero della Francesca’sDe prospectiva pingendi: it is the one preserved in the Panizzi Library in Reggio Emilia, which contains some corrections and annotations by the artist but is not entirely autograph. The next two rooms delve into the interests and ideas of Francesco di Giorgio Martini, the architect who designed the Palazzo Ducale in Gubbio: treatises and architectural elements, the latter largely from Gubbio, follow one another to restore the image of an intellectual who took as his model the building art of the Romans, who looked to antiquity and who took an interest in architecture from a very young age, as attested by a youthful Annunciation on loan from the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Siena, circa 1470, in which a significant role is attributed by the artist to the architectural wings that serve as a backdrop to the encounter between the Virgin and the angel.

The great ballroom of the Ducal Palace houses the section on the arts in Gubbio in the mid-15th century, a period dominated by the figure of Ottaviano Nelli, to whom the city has moreover dedicated a major monographic exhibition between late 2021 and early 2022: An important sample of his art, of which several examples can be admired in the city’s museums, churches and palaces, are the monochrome frescoes from Palazzo Beni, works from the 1520s that testify to the late Gothic culture of an artist who was particularly appreciated by local patrons, to the point of becoming one of the most prominent figures in the city (he was also among the consuls of Gubbio when, on August 7, 1444, Federico da Montefeltro, who had just become lord of Urbino, visited the city for the first time as a sovereign). The blossoming of the arts and the considerable influence exerted by Ottaviano Nelli are testified by a succession of important works that show how, on the one hand, the court of the Feltresca court had attracted artists to the city, even from distant regions, who concurred, in certain spheres, to give life to a true “Montefeltro style,” as the curators suggest, and on the other hand how the fate of Gubbio painting was linked, in terms of stylistic tangencies and cultural provenance of its main exponents, to that of nearby Perugia. Among the main results of the cultural influence that the court exerted on the tastes of Eugubine families are the painted cassoni, which abound in Feltresque Gubbio and of which a number of notable examples are on display in the exhibition, such as the panels arriving from the Musée National de la Renaissance in Écouen, elegantly decorated with scenes in which episodes from the Iliad are painted as if they were dreamy courtly fables, and of course with an abundance of gold to respond to the patrons’ desire to furnish their homes with a luxurious object. Gubbio painting, on the other hand, is investigated with some works that give the visitor an account of the transition from an essentially late Gothic culture, persisting in the city even after the disappearance of Ottaviano Nelli around 1450, to a new Renaissance language also promoted by the construction site of the Ducal Palace, the “first, intentional and very strong act of negation of the medieval architectural heritage and more generally of the late Gothic culture persisting beyond the mid-fifteenth century,” scholar Ettore Sannipoli has written.

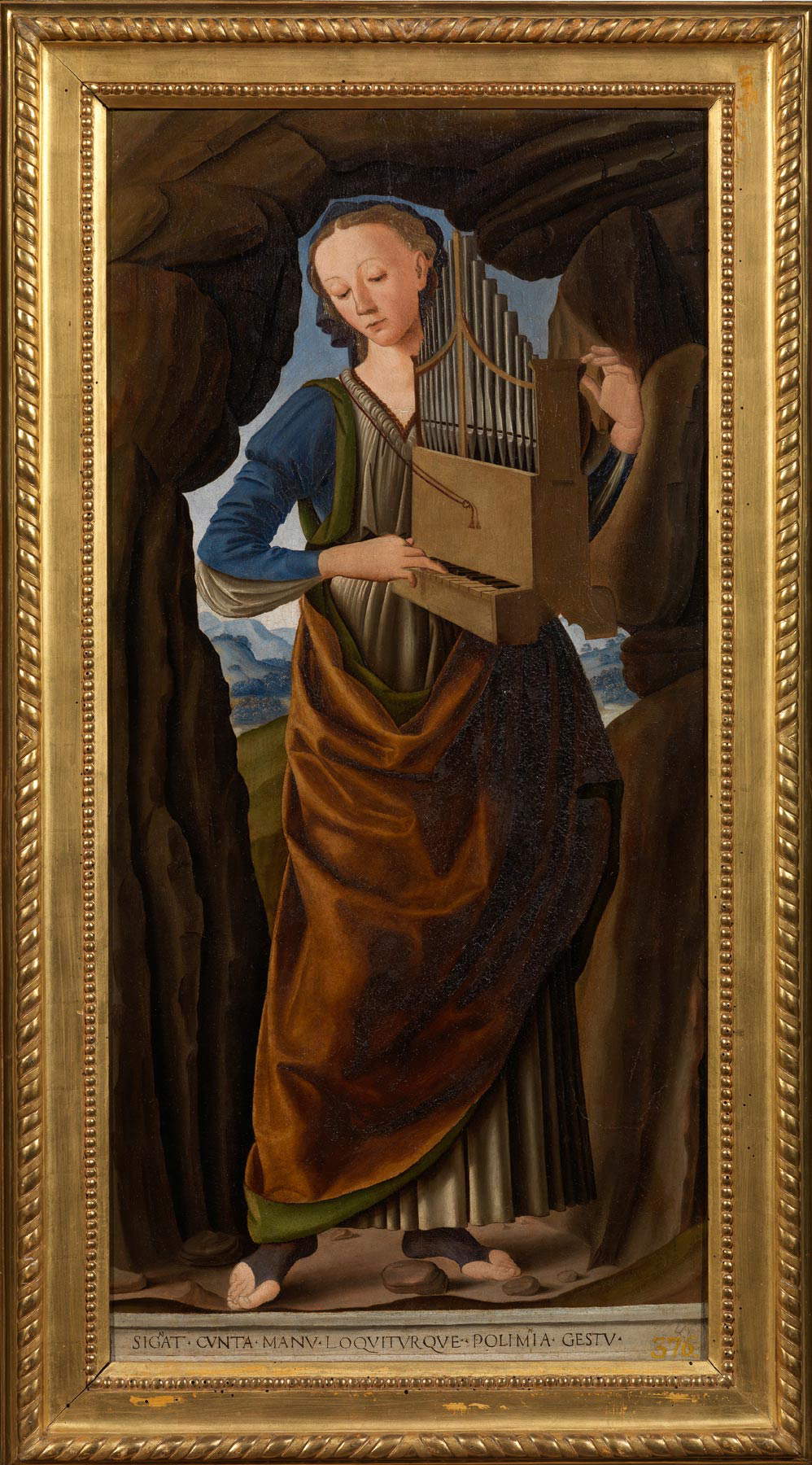

There follow two panels by Iacopo Bedi, works still inscribed in late Gothic culture but not insensitive to the new grammar, a Madonna and Child Enthroned between St. Augustine and St. Francis by Orlando Merlini, an artist already fully Renaissance who came from the Perugia of Bartolomeo Caporali and Benedetto Bonfigli, to arrive at the most up-to-date artist, Sinibaldo Ibi, who in 1503 signed the gonfalon of St. Ubaldo, a work of Perugian culture, believed to be miraculous and for this reason the object of particular devotion by the people of Gubbio. In the section on applied arts, a spectacular badalone stands out; it comes from the church of San Domenico and is decorated to the enterprise of Federico da Montefeltro’s studiolo mentioned at the beginning: it is the work of an artist who shows skillful mastery of perspective marquetry and thus restores two convincing images of loggias within which books are piled. The first part of the exhibition closes with a section on music: here we find the Muses of Giovanni Santi, Raphael’s father, depicted as musicians, each with her own instrument, offering an effective visual representation of the duke’s musical interests (as well as of the instruments he himself owned and would have depicted in the decorations of the studiolo).

Giovanni Santi,

Giovanni Santi,

The section of the exhibition hosted at the Palazzo dei Consoli welcomes the visitor with a life-size, realistic, seated, tired, sleeping armiger carved by Austrian Hans Klocker: in ancient times he was part of a group staging the Resurrection of Christ, and the uniqueness of the soldier lies in the fact that he is dressed in contemporary armor. “To actualize the Passion,” Fulvio Cervini writes in the catalog, “is to meditate on the fact that our violence continues to kill Christ, but through the virtuous use of military force we can move on to his luminous side. Perhaps this is also why Klocker’s soldier is defined in the smallest detail: a wooden warrior, just as a fighter is an iron sculpture.” Federico da Montefeltro embarked on his military career at a time in history when warfare underwent a transformation, and the exhibition intervenes to demonstrate this not only with the military treatise books and weapons lined up in the room (which testify to the modern evolution of weapons, in a transitional age in which firearms did not yet appear systematically, although they began to enter the collective imagination, and in which crossbows, large Pavia shields, bulky steel armor, often true masterpieces of craftsmanship, dominated, since even war, for the mentality of the time, was an opportunity to show off one’s taste), but also the numerous books that offer a summary of the culture and studies with which the future Duke of Urbino was formed: in the 15th century, the idea that there cannot be a good commander without a good culture was affirmed, since culture was considered the basis for conducting a war in a reasonable manner, and at the same time for transmitting its memory in the most fitting manner when hostilities were over. “A war,” Cervini further points out, “was worth most of all if a memory of it remained,” and this awareness “is revived in the Italian Renaissance courts and finds in Federico da Montefeltro an interpreter of original intelligence, who genuflects at the feet of the Virgin or opens books in the studiolo wearing the same armor with which he fights.”

The arts thus concur in recounting the war to celebrate the power of those who had fought it, and at the same time the battlefield becomes one of the places where the tastes and ideas of those who went to fight were expressed. It is therefore not surprising to find, even in the works of the time, numerous examples of ancient scenes in which combatants wear modern armor: in the exhibition, the public will therefore encounter works such as the Battle of Pidna, a complex painting that the curators of the Gubbio exhibition display with attribution to Verrocchio and workshop, where an episode from ancient Roman antiquity, the battle that pitted the Romans against the Macedonians in the last clash of the Third Macedonian War, is transposed into the contemporary, or like Girolamo Genga’s Martyrdom of St. Sebastian, which dresses the martyr’s tormentors in garish Renaissance garb, intent on piercing him with crossbow blows.

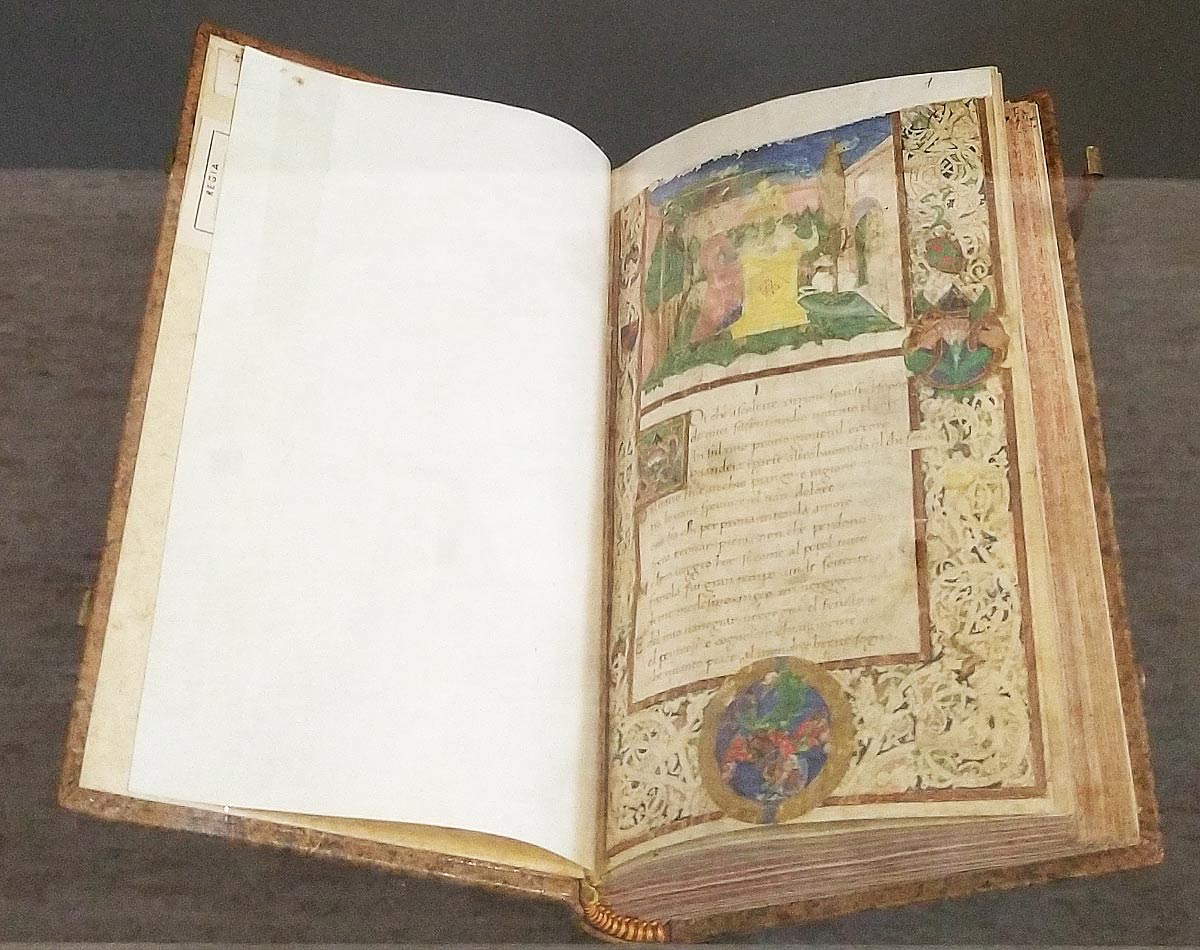

As for Federico da Montefeltro’s education and culture, a subject that as we have seen is deeply related to his military activity, we can imagine that he received his basic education in Gubbio, after which we know he spent a two-year period, between 1434 and 1436, at Vittorino da Feltre’s Ca’ Zoiosa, perhaps the most important school for future members of the ruling class of the time. It was here that Frederick began to cultivate his interests in ancient culture while learning his first military rudiments. On the literary side, his education took place mainly on books in the vernacular (though of course there is no shortage of fundamental classical texts), and a few essays from the volumes that must have inspired him are on display in the exhibition: there is Dante’s Commedia (with an important illuminated copy now in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana but made for Frederick’s personal library), there is no shortage of Petrarch’s Canzoniere and Trionfi (with a copy that belonged to Alessandro Sforza, lord of Pesaro and Frederick’s father-in-law), there are books by Dante’s commentators.

The third and last chapter of the exhibition is set up in the Museo Diocesano, in a room where Federico da Montefeltro’s astrological interests are summarized through texts that attest to the knowledge of the time about stars, stars and planets, and then more astronomical and astrological instruments that moreover find correspondence in the inlays of the studioli in Urbino and Gubbio, paintings and even amulets and talismans, similar to those painted in the works of the time (the most best known is the coral around the Child’s neck in Piero della Francesca’s Madonna di Senigallia preserved at the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche in Urbino: are recalled in the exhibition by sprigs and necklaces on loan from the National Archaeological Museum in Perugia, objects to which a significant apotropaic value was attributed). The visitor is introduced to the room by a fragmentary Urania from the early 16th century, a fresco torn and transferred to canvas, attributed to Amico Aspertini: Urania was the muse of astronomy and astrology, and she is depicted holding a globe, similar to the one, on loan from the National Archaeological Museum in Ancona, which is displayed next to her, and which dates back to the 1st-2nd century AD, an instrument with which the ancients tried to interpret, read and understand the sky. On display next to the globe are instruments for measuring the distances of the sky and the earth: an armillary sphere, a compass and a quadrant, which are punctually reflected in the wooden inlays of the studioli, and which do not contradict Federico da Montefeltro’s well-known religiosity.

On the contrary: his astrological interests could almost be considered a reflection of his pious sentiments. “This harmony of harmonic consonances,” Patrizia Castelli explains in the catalog, “must be [...] understood in a profoundly religious way insofar as it constitutes itself as an essential means of reaching the divine sphere, in accordance with what Marsilio Ficino theorized.” The Duke of Urbino’s curiosity is reflected in the treatises of the time: the exhibition presents for the first time the prognostications of Paolo di Middelburg, who was court astrologer in Urbino from 1481 until 1508, and who in his writings examined horoscopes, birth dates, and astral motions in an attempt to make predictions about what would happen (interestingly, in the prognostications of 1481 and 1482, Paolo di Middelburg “justifies the accuracy of his calculations on the basis of the use of the armillary sphere,” Castelli notes). A prominent place in the exhibition belongs to Marsilio Ficino’s Disputatio contra iudicium astrologorum, a critique of the discipline of judicial astrology, i.e., the branch of astrology that purported to foretell the future (in particular, Ficino showed skepticism toward some predictions): the Tuscan humanist was, moreover, a figure particularly appreciated by the duke, and this esteem we know for certain was mutual.

The secentenary exhibition that Gubbio dedicates to its illustrious son is strictly tripartite, as we have seen, but the sections together create an itinerary that, apart from a few moments of weakness (the section on Frederick’s culture could have been more incisive and expanded more on the context, would not have been weighed down: a visitor unfamiliar with the history of the Renaissance might, for example, not fully grasp the importance of Federico da Montefeltro’s education at Ca’ Zoiosa), gives rise to a harmonious and unified discourse that does not suffer from being divided over three different museums (moreover, all very close and reachable from each other with a few minutes’ walk). Federico da Montefeltro and Gubbio. Lì è tucto el core nostro et tucta l’anima nostra is a high-level project, well-orchestrated in its arrangement along the three venues, and brilliantly nourished by its relationship with the territory: at the Diocesan Museum the works in the exhibition dialogue excellently with the permanent collection (the chapter set up here, after all, also touches on religious themes), at the Palazzo dei Consoli the theme of Feltresque culture is also central to framing the temperament of the time (dating back to 1456 one of the founding moments of the community of Gubbio, the Municipality’s purchase of the Tavole Iguvine, perhaps, the curators suggest, at the urging of Frederick himself “as evidence of the ’antiquity’ of the territory under his jurisdiction”), while at the Ducal Palace, on the piano nobile, the public can further explore the theme of the arts in Gubbio in the period of reference with other works by artists on display. Without calculating that, as is natural, the beauty of this exhibition lies precisely in its ability to implicitly invite the public to discover, throughout the city, further traces of Renaissance Gubbio.

Federico da Montefeltro emerges from the exhibition as a complex figure, presented to the visitor in his singularities between public image and private dimension, in an itinerary that also manages to be free of that celebratory rhetoric that has sometimes been seen accompanying exhibitions organized for anniversaries and recurrences: the strength of Federico da Montefeltro and Gubbio. Lì è tucto el core nostro et tucta l’anima nostra lies in being, first and foremost, an exhibition of history and art, strong in its solid structure, which required careful preparation, which is well developed through the three venues, and which succeeds in making the exhibition go beyond the dimension of “homage” to the duke. At the time of this writing, the complete catalog of the exhibition has not yet been published: however, the curators’ essays have been made available, which nonetheless suggest that the supporting publication to the exhibition will be a volume that will not lack those qualities befitting a review such as the one the public can see in the three Eugubine museums.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.