The novel of Lorenzo Lotto's life, narrated by Stefano Zuffi

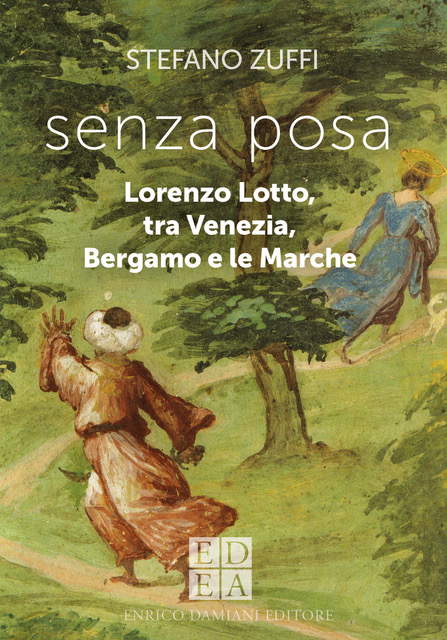

Art historian Stefano Zuffi ’s third book for Enrico Damiani Editore: after comparing, in parallel, the lives of Raphael and Mozart and those of Giotto and Dante, this time Zuffi is publishing with the Brescian publishing house a fictionalized biography of one of the most eccentric artists in art history: Lorenzo Lotto (Venice, 1480 - Loreto, 1556). The book, entitled Senza posa. Lorenzo Lotto between Venice, Bergamo, and the Marches(160 pages, 16 euros, ISBN 9791254560150, also in ebook format at 6.99 euros), is dedicated to the artistic and biographical story of the Venetian painter, assuming that Lotto did not have an easy life. Far from it: his destiny, says the author, would have been to “struggle” throughout his existence, as his surname ironically suggests, and as Lorenzo Lotto himself will have the opportunity to recount within the pages of the book.

The book retraces the artist’s vicissitudes in a fictionalized form, following Lorenzo Lotto as he wandered through the Veneto region where he was born, from which he would later move away only to return and find himself in competition with Titian, Lombardy, the Marches, Bergamo until he reached the final destination of his journey, the sanctuary of Loreto. The story starts right here, from the Sanctuary of the Holy House, where the elderly painter, by now at the end of his days, meets the prelate Gaspare Dotti, his last patron, and to him he entrusts the story of his entire life, as in a sort of long confession through which Zuffi traces the threads of the human and artistic story of an artist whom Pietro Aretino, in a letter capable of arousing mixed feelings,had called “more than goodness good and more than virtue virtuous.”

The story begins on an afternoon in September 1554: Lorenzo Lotto is seventy-four years old, a very advanced age for the time, but he is still at work, and we see him at the beginning of the essay-romance as he strides in his smock, in slippers, moving among the ground earthenware and some drawings, waiting to prepare to receive the visit of Dotti, protonotary apostolic, former commissioner of the Holy Office, and for a few years governor of the sanctuary of Loreto. Dotti, a Venetian like Lorenzo Lotto, is eager to know the painter’s life story, and his curiosity is satisfied: in fact, Lotto starts with a long account from his youth to his decision to move to Loreto, where he will take his vows as an oblate and spend the last days of his existence.

In between, a life spent in the shadow of the greatest, told by a passionate painter still frustrated by failures and proud of the few happy years. The novel follows the tale of Lorenzo Lotto first in Treviso where the artist works for his first major patron, Bishop Bernardo de’ Rossi, then in Rome, when the painter is eager to show off but is overwhelmed by the success of Raphael, and then again in the first interlude in the Marche and the golden years of the Bergamasque period, then again in Venice in an attempt, which will prove fruitless, to compete with Titian. Disappointment at seeing his rival at the head of a thriving workshop, organized almost as a sort of arsenal, with a host of collaborators preparing paintings and his brother beating the drum with wealthy patrons, and the realization that he would be reduced to working for invariably less prestigious clientele than Titian’s and for paltry fees, would lead Lotto to mature in his decision to retire to the Marche region that had given him so much satisfaction in his earlier years, but not before making a will in favor of the children of the hospital. Until, in the finale, Lotto will make an important revelation to Monsignor Dotti.

There is no lack of narration of the individual works, which Zuffi imagines coming directly from the mouth of Lorenzo Lotto himself, who in the first person comments on his best and least successful works together with his illustrious patron: from the celebrated portrait of Bernardo de’ Rossi to the wooden inlays in Santa Maria Maggiore in Bergamo, from the polyptych in Recanati to the frescoes in the Suardi Oratory in Trescore, from the Rosario altarpiece in Cingoli to the last works executed in Loreto, Lorenzo Lotto’s masterpieces are condensed into a narrative that becomes increasingly pressing, despite the fact that the painter, due to age-related fatigue, has to take long breaks between stories.

With a novel in a dry, light, fresh and almost colloquial style, and with a historical reconstruction based on artworks and documents (such as letters, the artist’s personal notes, and his will), Stefano Zuffi engages the difficult challenge of reconstructing the character of Lorenzo Lotto, seen as a good-hearted man and as an artist who saw work as his main reason for living, and who relives his torments and passions, his few joys and his many disappointments. All this by setting the narrative in the context of early 16th-century Italy: in the background the great artistic construction sites of the time, the wars of Italy, the changes in a society that was undergoing a radical transformation, and in the foreground the deeply human story of one of the most talented artists of his time, who came to the end of his days almost destitute, inadequately recognized in life, in whom, however, we can today identify one of the most imaginative and nonconformist geniuses of all time.

|

| The novel of Lorenzo Lotto's life, narrated by Stefano Zuffi |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.