by Redazione , published on 12/03/2020

Categories: Art and artists

/ Disclaimer

Third installment of the focus on the restoration of the Polyptych of the Mystic Lamb. The first and second phases of the restoration are discussed.

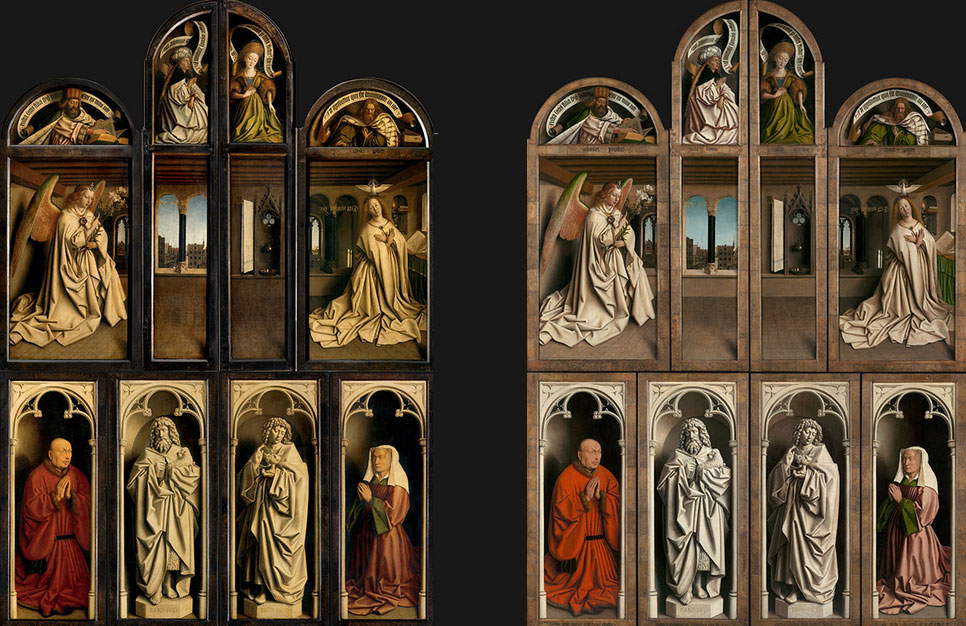

A long and complex work, started in October 2012, divided into three phases, with the first two finished and the third one still being worked on: this is, in a nutshell, the restoration of the Polyptych of the Mystic Lamb, the masterpiece created by Jan van Eyck (Maaseik, c. 1390 - Bruges, 1441) and his older brother, Hubert van Eyck (? - Ghent, 1426), and preserved in the Cathedral of St. Bavon in Ghent, Flanders. In this third installment of our focus devoted precisely to restoration (in the first we talked about the history of previous interventions and materials, in the second about the survey campaign), we delve precisely into the first two phases of the intervention, carried out by technicians from the KIK-IRPA (Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage) in Brussels, under the direction of Hélène Dubois, costing 2.1 million euros and financed 80% by the government of Flanders (equally divided between the Flanders Heritage Agency and the Department of Culture, Youth and Media, which supported the restoration with 40% each) and the remaining 20% by the Baillet Latour Fund (a nonprofit foundation that, since 1974, has been supporting arts and culture). The first phase, which lasted exactly four years (October 2012 to October el 2016), focused on the exterior panels, the ones that can be seen when the van Eyck brothers’ complex machine is closed: the four panels with theAnnunciation, the two sibyls and the two prophets in the cymatium, and the four panels in the lower register (on the sides the depictions of the patron, the nobleman Joos Vijd, and his wife Lysbette Borluut, and in the center the two saints in grisaille, namely John the Baptist and John the Evangelist).

The first evidence, which also emerged from the survey campaign carried out over a two-year period before the restoration, was that a large part of the panels had been covered with repainting, dating from different dates (but mostly concentrated between the 16th and 17th centuries: in any case far removed from the date of the polyptych’s completion, which the van Eyck date 1432 with an inscription), and extended over about 70 percent of the pictorial surface. In the case of the frames, the repainting had instead affected the entire surface, so much so that, before the restoration, the frames were completely altered, with a significantly darker and radically altered color than the original. In short, from the seventeenth century until today no one had been able to see the Polyptych of the Mystic Lamb as it originally appeared. Not only that: the repainting itself was obscured by yellowed paint that covered much of the work. And as is the case with all restorations that present similar situations, this time as well the technicians and internazonal experts called upon to express their opinion on what to do wondered about the advisability of removing the repainting: this was also the case with the previous restoration of 1950-1951 (carried out by Albert Philippot), when it was decided to carry out only a conservative intervention without altering the appearance of the work. This time, however, the opposite was decided upon: in fact, the restorers realized that it was possible to remove the repainting without causing damage to the painting, given that (as we also saw in the second installment of this special), the polyptych was in substantially good health, and that the most susceptible areas (i.e., those at risk of losing portions of the painting) had already been secured with an urgent intervention directed by Anne van Grevenstein in 2010.

|

| The restoration workshop at the Museum voor Schone Kunsten in Ghent. |

|

| The closed polyptych, before and after restoration |

The first step was the transfer of the panels from the Cathedral of St. Bavon to the Museum voor Schone Kunsten in Ghent (where, moreover, the major exhibition on Jan van Eyck, the largest ever monograph on the Flemish painter, is being held until April 30, 2020), which was identified as the most suitable place to conduct the operations, partly because of the fact that the public would be able to follow it in real time. As indeed it was: visitors to the museum passed in front of a room-laboratory with large windows (eleven meters long and one meter and seventy meters high) that allowed them to see what the restorers were doing at the moment. The climatic conditions necessary for the proper conduct of all the work had obviously been created in the room, with humidity kept constant at a level of 60 percent, and neutral light specially designed to reduce glare. Once the laboratory was set up and the transfer completed, it was therefore first possible to thoroughly evaluate the support (which had undergone a minor treatment, given its good condition: only the most obvious fractures, which were in any case a minor problem, were healed), and then to proceed with the work on the frames of the compartments, the first element of the polyptych to receive the care of the restorers. As mentioned, they had been completely repainted: six of them had been covered with a bronze-colored patina, while the frames of the two central panels of theAnnunciation (the one with the city view and the one with the interior view), even, had been covered in black. It was not possible to fully recover the original appearance of the frames, because the repainting had altered mainly the enamels that Van Eyck had applied to them, but it was still possible to observe how the artist had envisioned an elegant structure worked in silver leaf with small, colored, punctiform inserts, with the intention of imitating stone arches-an impression that had been lost due to the overlays.

Next, the restorers dealt with the removal of the varnish, which yielded two important results: on the one hand, an aesthetic result, since it was possible to remove the most superficial yellow patina, and on the other hand, it was possible to understand what the real extent of the repainting was. With the paint removed, each individual portion of the surface was analyzed in order to understand when the overlays dated back to. We do not know much about the varnishes that were in use in the fifteenth century, since they were often removed during restoration operations (and, as seen in the first installment of this focus, from this point of view the Polyptych of the Mystic Lamb has had a rather troubled history). The varnish, which serves to protect the painting from the action of external agents, when applied is transparent and does not alter the perception of the colors, but depending on the compounds with which it was manufactured here, it can undergo oxidation processes that, on the contrary, change the appearance of the work, making it appear yellow, and going to impact very strongly on the legibility of the painting. One example is the ketone-based varnishes used after the 1950-1951 restoration: these are materials that not only tend to yellow over time, but also become more difficult to remove. The very presence of these paints was one of the main reasons why the decision was made to begin the lengthy restoration. The removal was conducted with the use of special solvents, also chosen because of the type of varnish the restorers were facing in the various portions of the painting’s surface.

|

| One of the frames after restoration |

|

| Removal of varnish on the figure of St. John the Baptist during the restoration (already removed on part of the robe, the lamb and the right half of the arch) |

|

| Removal of paints on the right sibyl during different stages of operations |

|

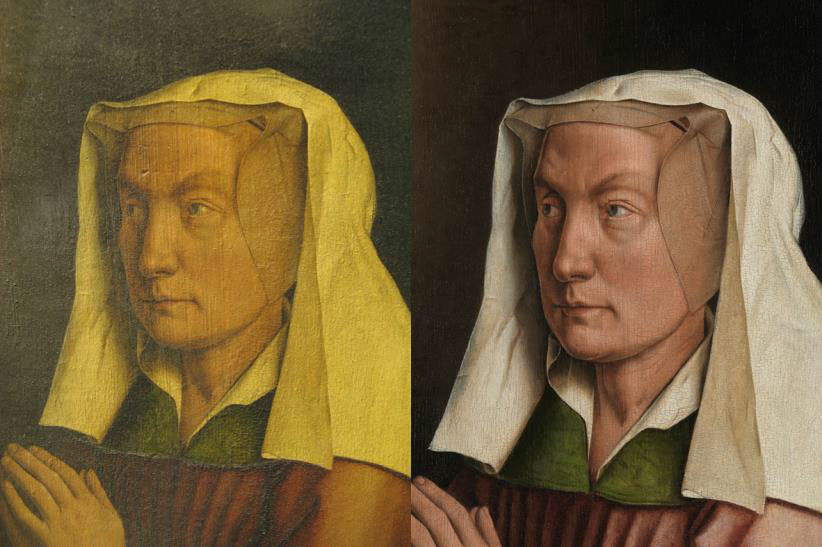

| Removal of paints from the figure of Lysbette Borluut, before and after treatment |

The restorers, having reached this point, continued with the removal of the repainting. In ancient times, there were mainly two reasons why new layers of paint were spread over the surface of a painting after time (even centuries): on the one hand, because the painting was getting ruined and repainting was the only known way to repair the damage, and on the other hand (less frequent, but the case also occurs for the Polyptych of the Mystic Lamb), to update the work as the aesthetic canons of an era had changed (it occurred, as we have also explained on these pages, for the snout of the lamb protagonist of the van Eyck brothers’ painting). And it is not always easy to remove repainting, because in ancient times painters used the same materials used by their predecessors. In the case of the Polyptych of the Mystic Lamb, as discussed in the episode on the investigation campaign, various techniques (radiography, X-ray fluorescence, infrared reflectography) were used to examine the individual repainted portions and to figure out how to proceed with their removal. This operation is perhaps the most delicate of the procedure, because it must be conducted on millimeter-sized areas of the painted surface, with the use of a special chisel, to be maneuvered with the aid of a binocular microscope, and sometimes through the use of solvents or other tools. Once this operation has been completed, there are two next steps to be taken: the first is to secure what has come back to light, in order to ensure solidity and stability of the original materials. Consolidation is especially important in those areas where there is lifting of the pictorial film: in this case, the few portions that had this problem were secured with the use of isinglass, applied with the help of Japanese paper and very thin brushes, to make the raised parts adhere to the surface (the Japanese paper is removed when the glue dries).

The second is to compensate for gaps: indeed, it may be the case that significant portions of the painting have been lost, and in this case restorers use techniques as identical as possible to those used by the author of the work in order to supplement it in the most appropriate way (or, in the case where it is not possible to resort to fifteenth-century techniques, modern colors are used that nevertheless imitate ancient ones: this was done for the Polyptych of the Mystic Lamb). Restoration, in this sense, aims to restore the painting to its integrity. It is done, however, in such a way that the additions do not go to cover the surviving original parts, and are reversible, so that they can be easily removed in the future in case a new intervention is needed (this, at least, modern restoration practice prescribes in cases like these). To ensure that original and “retouching” remain separate, KIK-IRPA restorers covered the painting with a thin layer of dammar resin-based varnish, over which they then applied a first layer of base color, which then received a new layer of varnish, over which in turn pigments were applied in progressive layers. This was completed with a new layer of varnish that received special Gamblin colors (these are colors specifically designed for restorations, which are easy to remove), and then a final layer of Damar resin-based varnish to even everything out.

|

| Removal of repainting |

|

| The repainting on the figure of Lysbette Borluut |

|

| St. John the Baptist before and after repairing the gaps |

|

| Restorer performs the restoration of the gaps |

|

| Restorer operates the repair of the gaps |

|

| The KIK-IRPA team at the end of the second phase of restoration |

The first phase of the restoration thus yielded several important results: the discovery of the original colors of the prophets, the sibyls, and the figures of the patrons; the acquisition of a great deal of information about Jan van Eyck’s painting technique (it is to him that critics tend to assign the figures of the closed panels, while the three central figures of the open polyptych are usually traced back to Hubert, although scholars are not certain), the full recovery of the figures of St. John the Baptist and St. John the Evangelist, which Jan had painted in imitation of two statues, the recovery, again full, of the frames, the achievement of a better legibility of the painting, the possibility of admiring again the amazing perspective illusionism of theAnnunciation scene.

The same operations were repeated during the second phase of the restoration (which lasted from November 2016 to December 2019), which involved the lower register of the open polyptych (including the panel with the modern copy of the intact Judges panel, which as is known was stolen in 1934 and then replaced: it too needed restoration) and was the one that had the greatest media resonance, given the results achieved with the Lamb. Before getting the panels to the Museum voor Schone Kunsten in Ghent, those that had already been restored were returned to St. Bavon Cathedral: the public that visited the cathedral during all phases of the intervention was never left completely without the polyptych. In the case of the lower register of the open polyptych, it was discovered that the repainting affected 50 percent of the surface in the central compartment (the one with the scene of theAdoration of the Mystic Lamb) and about 10 to 15 percent of the side panels, and here, too, the restorers followed the same procedure as in the first phase: removal of the paint and repainting, consolidation, and repair of the gaps. The original painting was in an excellent state of preservation: only 5% of what the van Eyck brothers painted is estimated to have been lost.

The restoration is not yet finished: 2020 is the year of the third phase, that of completion with the restoration of the upper register of the open polyptych. In the meantime, the public can see the panels that have already been restored: those from the second phase in St. Bavon Cathedral, where they returned on January 24, and those restored during the first phase are instead featured in the exhibition Van Eyck. An optical revolution, the major exhibition at the Museum voor Schone Kunsten in Ghent: they will return to the house of worship in May. The public will be able to return to see the entire assembled polyptych starting Oct. 8, in St. Bavon Cathedral in Ghent.

|

| Focus restoration of the Polyptych of the Mystic Lamb. Third installment: phases 1 and 2 of the restoration |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.