Futurism: origins, development and main exponents of the avant-garde movement

Futurism was an artistic movement born in Milan in the early 20th century, and is considered the most important, if not the only, Italian avant-garde movement of the early 20th century. It was conceived and founded by writer and poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (Alexandria, Egypt, 1876 - Bellagio, 1944), who identified in a series of dictates to be followed in culture, art and even life a way to achieve renewal in people and society, avoiding and often repudiating all that had taken place in the past (hence the name of a movement inevitably projected into the future, according to its proponents). Futurism started from literature and spread to a variety of fields, namely art, music, architecture, theater, dance, cinema, and even fashion and gastronomy.

The context in which it was born was characterized by major changes that were taking place in Italian society. Technological modernization, with the advent of cars, radio, the first airplanes and movie cameras, had indeed brought a wave of novelty, which fascinated the public and generated the myth of speed and dynamism. The movement succeeded in intercepting these changes and making them its own, leveraging precisely the break with the past and the search for unprecedented modes of expression. The ’impetuosity, both in words and in the way of relating as well as in painting and sculpture, is one of the main characteristics of the works and statements of the exponents of the current, to get the message of modernity across directly and clearly.

Futurism contributed, moreover, to the affirmation of Italian culture in the world, becoming one of the most widespread and well-known Italian art movements abroad. Crucial in this was Marinetti’s commitment to making the artists known throughout the world through exhibitions, conferences and distribution of posters.

Origins and Development of Futurism

The date that marks the beginning of the movement is February 5, 1909, the day the Manifesto of Futurism, written by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, was published in the Gazzetta dell’Emilia. The manifesto would later also be published in French, in Le Figaro, fifteen days later, on February 20, 1909. The writer is believed to have drawn his inspiration following an accident with his automobile in 1908. Trying to avoid two bicyclists, he swerved sharply and due to the high speed fell into a ditch, managed to get out of it, and after being pulled out he felt like a different, new man, eager to bring about a revolution in culture by eliminating all unnecessary trappings.

All the founding principles of the movement, based on the ’exaltation of boldness, courage and modernity, and the clear refusal to look to the past, to focus rather on the present and the future, defined as “absolute,” were given in the writing. The manifesto’s points also include a boycott of the places entrusted with the custody of works of art and literature, namely museums and libraries, and the exaltation of “war as the only hygiene of the world.” Indeed, for the Futurists, war was also synonymous with modernity, and almost all exponents voluntarily enlisted to fight in World War I. Futurism always received criticism for this aspect.

About a year after the publication of the Manifesto of Futurism, a group of artists consisting of Umberto Boccioni (Reggio Calabria, 1882 - Verona, 1916), Carlo Carrà (Quargnento, 1881 - Milan, 1966), Luigi Russolo (Portogruaro, 1885 - Laveno-Mombello, 1947), Romolo Romani (Milan, 1884 - Brescia, 1916) and Aroldo Bonzagni (Cento, 1887 - Milan, 1918) signed the Manifesto of Futurist Painters. From this episode the artistic current was born. The text of the manifesto was drafted concretely by Boccioni, Carrà and Russolo, while Romani and Bonzagni only signed it and soon after left the movement, replaced by Gino Severini (Cortona, 1883 - Paris, 1966) and Giacomo Balla (Turin, 1871 - Rome, 1958).

The manifesto was read publicly on March 8, 1910, during an evening organized at the Chiarella Politeama theater in Turin, but they were met by the audience with a succession of whistles and protests.

Soon afterwards it was the turn of the Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting, in which the concept of “congenital complementarism” was made explicit and “universal dynamism” introduced. Congenital complementarism was based on the idea that objects and planes were not to be considered as separate sections, as had hitherto been the convention in art, but rather as interconnected and related to each other. The manifesto read, “Our bodies enter the couches on which we sit, and the couches enter us, just as the passing streetcar enters the houses, which in turn are thrown onto the streetcar and amalgamated with it.” The choice of colors, shapes and lines takes into account this aspect, which also engages all the senses of the viewer on an emotional level, as the focus of the work itself and not as a mere observer. In addition, in the text, stridents were launched against all academies, which represented the past to be fought by all means.

Often the Futurists became the protagonists of impetuous episodes that went down in history, such as the so-called “punitive expedition” of 1911 in Florence. In an article published in La Voce in 1911, the writer and artist Ardengo Soffici (Rignano sull’Arno, 1879 - Vittoria Apuana, 1964) panned their work and even indulged in rather personal judgments (“foolish and laid smargiassate di poco scrupolosi messeri...”). Learning of Soffici’s words, Marinetti, Boccioni, Russolo and Carrà left for Florence to track him down at the Caffè Giubbe Rosse, where the editors of La Voce used to meet. Once they arrived, scuffles began caused by a slap Marinetti gave Soffici. Yet, although the relationship between them was so troubled, only a few years later Soffici was among the founders of the futurist magazine Lacerba. It was, moreover, thanks to Soffici that the Futurists began to learn about Cubism, an avant-garde that was spreading in Paris and that was a great inspiration for some of its exponents. Many assimilated the novelties proposed by the current and reworked them to infuse new impetus into their painting. Several of them, however, always remained at a distance from it, having developed the conviction that the Cubists decomposed objects while ignoring movement altogether, and thus were still far too traditionalist. Thus, they began to experiment with a type of synthetic representation in which different moments, movements and emotions converged.

Marinetti meanwhile had come to the conclusion that the time was ripe to make the movement known abroad as well, so he organized a number of exhibitions in Paris, London, Berlin and other European cities. In 1914 he traveled in person to Russia to meet with local artists who had joined the movement. That same year, however, the relationship between Marinetti and Soffici soured again to the point of an official rupture, sanctioned by an editorial published in Lacerba openly in polemic against the movement’s founder. The Futurists also began new experiments in the plastic sphere, with the use of different materials and the union of different artistic disciplines, once again challenging conventions. A new manifesto entitled Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe (1915) was published, theorizing the fusion of the arts into one total art. But the outbreak of World War I shortly thereafter ended the first phase of Futurism, with the death of some important names such as Boccioni and the abandonment by other artists, who tried their hand at other avant-gardes.

Later Futurism got a new boost in the city of Rome, specifically in the studio of Giacomo Balla, who attracted a group of new recruits to himself. It was the critic Enrico Crispolti, in the late 1950s, who was the first to speak explicitly of a division between “First Heroic Futurism,” with the founders and early exponents, ending with World War I, and “Second Futurism.” Not a few difficulties conditioned this new Roman phase, as the tendency toward a return to order was becoming increasingly widespread, partly as a response to the dramas experienced as a result of the conflict. Futurism was perceived as a movement belonging to the past, and it was no coincidence that in 1920 a new manifesto with the emblematic title Contro tutti i ritorni in pittura, signed by Leonardo Dudreville, Achille Funi, Luigi Russolo and Mario Sironi, was drafted to reinforce their visions. To reinvigorate the current, Marinetti and others began experimenting with different and innovative art forms such as Futurist fashion, whose dictates were made explicit in the manifestos Il vestito antineutrale (1914) and Manifesto della moda femminile futurista (1920), andfuturist ’furniture, so as to bring their art into everyday life. In 1930 Marinetti also drafted a manifesto dedicated to cooking, abolishing pasta as it made man slow and weighed down, and disserting on the sense of taste, usually never dealt with in art. Some of the movement’s artists also began to devote themselves to advertising graphics, attracted by the opportunity to get their innovations to a very large number of people: in this sphere the Trentino artist Fortunato Depero (Fondo, 1892 - Rovereto, 1960), author of graphics still used by companies today, stood out in particular. Finally, the last strand of Futurism concerned ’aeropittura, or works that exalted the world of aeronautics. Other areas of focus were music and theater sets. In the first case, the main protagonists were Francesco Balilla Petrella (Lugo, 1880 - Ravenna, 1955) and Luigi Russolo, who introduced the concept of noise and also created new musical instruments, the so-called “intonarumori,”" while set designs were especially taken care of by Enrico Prampolini (Modena, 1894 - Rome, 1956).

Finally, the Futurists were particularly attracted to the construction of the first skyscrapers, considered a symbol of modern man’s conquest of the sky. The skyline of New York City, dotted with these towering buildings, often recurred in illustrations and advertising graphics. Already in 1914 architect Antonio Sant’Elia (Como, 1888 - Monfalcone, 1916) had drafted the Manifesto of Futurist Architecture, outlining all the characteristics of an ideal “futurist city, similar to an immense tumultuous building site, agile, mobile, dynamic in every part, and the futurist house similar to a gigantic machine.”

The characteristics, innovations and main exponents of Futurism

The Futurists found innovative ways of using lines, which they called “force lines”, placing them in various positions and making them functional in the composition of the work, no longer as a simple segment. The futurists’ palette was bright and bombastic and was based on thecontrasting juxtaposition of primary colors, without shading. They initially adhered to pointillism, a technique of applying color through close strands, which lent itself perfectly to both strong colors and the tendency to infuse their works with movement.

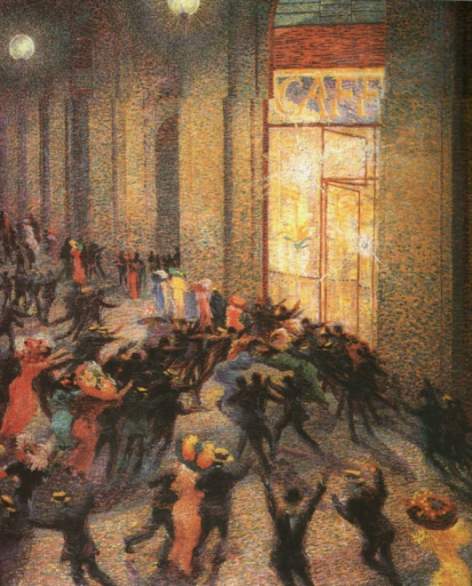

In fact, in line with the precepts of the Futurism Manifesto, the group initially devoted themselves to research on dynamism, taking urban scenes of everyday life as their reference. The movement’s earliest known works are Rissa in galleria (1910), La città che sale (1910) and La risata (1911), all by Umberto Boccioni. Within just one year, Boccioni had demonstrated progressive research, which led him to effectively render the sensation of movement and identify the most appropriate ways for the much sought-after interpenetration of planes. Following the early results, Boccioni produced the triptych States of Mind - Gli addi, Quelli che vanno and Quelli che restano (1911), to officially demonstrate his views on simultaneity, which he regarded as a mental condition in which the memory of particular events and personal emotional perception are joined together.

Of a different opinion, however, was Giacomo Balla, an artist who was older than the other members of the group by about ten years. According to Balla, dynamism resided solely in optical perception, so he focused on the sequential succession of the same image represented at different times. Emblematic were the 1912 works Girl Running on a Balcony, Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash and The Violinist’s Hand. These works were mostly figurative, while from 1912 Balla approached more abstract outcomes, including the series Iridescent Compenetrations (1912) and Automobile Speed (1913).

Carlo Carrà brought to the movement greater expressiveness, evident in Ritratto di Marinetti (1910-1911) and Funerale dell’anarchico Galli (1911). He was also the first to later insert words into paintings and to introduce the technique of collage, much akin to Cubism. After World War I, Carrà moved away from the movement to devote himself to metaphysical painting. The ’influence of cubism was also very evident in Gino Severini, who moved to Paris and came into direct contact with the works of this current. He remained very akin to the decomposition of forms, as can be seen in Dancer in Blue (1912), combining it with scenes of Parisian social life. He too later landed on abstract representation with Plastic Rhythm of July 14 (1913). But at the conclusion of the first phase of Futurism, Severini moved away to concentrate exclusively on Cubism.

Luigi Russolo often oscillated between Symbolism and Divisionism, eventually arriving at his first truly experimental painting, The Uprising (1911), in which through “force-lines” arranged in the form of arrows, he rendered the idea of the ’energy that spreads during a demonstration among the streets of a city. One finds again The “lines-force” also in Dynamism of an Automobile (1912-13), in which he represents the victory of the car over air resistance. Russolo devoted himself to Futurist music for a long time, so his pictorial output was less substantial than others.

Meanwhile, Boccioni also continued his research in sculpture over the years. He made in 1913 the very famous Unique Forms of the Continuity of Space, in which the body of the walking man is only intuited, not circumscribed by precise and definite lines, but by curves and a series of solids and voids that create plays of light and shadows. He thus gave birth to the first true dynamic sculpture, which expands in space in a fluid manner. The statue is featured on the 20-cent euro coins circulating in Italy.

In the second period of Futurism, several newcomers entered, including Fortunato Depero, a native of Rovereto and a disciple of Balla. In fact, he was much closer to him than to Boccioni.

The hallmark of Depero’s works was the use of human silhouettes that closely resembled puppets, to which he infused dynamism through diagonal foreshortening and bold, curved, straight or zigzag lines. The puppets were a clear reference to theater, and in fact around 1917 Depero had come into contact with the famous Russian ballets and created some costumes, eventually landing on the show Balli plastici, an avant-garde theatrical work. From that time on, the human silhouette first appeared in “Futurist tapestries” and then as a constant element of his art, which soon became very recognizable. Depero has, in addition, contributed to the history of advertising graphics, and many of his creations are still used today-just think of his contribution to defining the visual identity of the well-known drink Campari. In addition, Depero was a strong advocate of the need to bring Futurism into the everyday, and it was because of this strong conviction of his that the first “futurist art houses” were built in several cities in Italy. He also built one of his own in Rovereto.

With the start of the second Roman phase of Futurism, Balla became a point of reference for the young recruits, who were enriched by, among others, Gino Galli (Rome, 1893 - Florence, 1954) and Julius Evola (Rome, 1898 - 1974), while Enrico Prampolini, who had been somewhat defiladed up to that point, increasingly emerged. He, in the 1920s, had been one of the most determined promoters of “mechanical art,” paying homage to the beauty of the machine and its metallic gleams, along with Vinicio Paladini and Ivo Pannaggi. Finally, Prampolini, Fillia (Luigi Colombo; Revello, 1904 - Turin, 1936), Benedetta (Benedetta Cappa; Rome, 1897 - Venice, 1977), Gerardo Dottori (Perugia, 1884 - 1977), Nicolaj Diulgheroff (Kjustendil, 1901 - Turin, 1982), Tullio Crali (Igalo, 1910 - Milan, 2000), were the leading names of ’aeropittura, the last development of the movement before its conclusion.

Legacy of Futurism

Following the experience of Russian Futurism came the raggism of Michail Larionov and Natal’ja Goncarova , which was based on the study of the phenomena of light refraction. There are a number of well-traced influences of Futurism in numerous avant-gardes spread throughout the 20th century, including Dadaism, Surrealism, Arte Povera, and performance art. However, the exponents of these new avant-gardes would never admit this authorship, in adherence with the tendency of every avant-garde to reject everything that came before.

Moreover, Marcel Duchamp in his early works takes up the dynamic juxtaposition of moments in succession, as in the work Nude Descending the Stairs No. 2 (1912). He has often been juxtaposed with the Futurists because of this characteristic, yet his contact with the movement was certainly very meager, as several years had already passed since its diffusion.

Where to see the Futurists’ works

The largest nuclei of Futurist works are preserved in Italy between Milan and Rovereto, and abroad in New York, all cities closely linked to the history of the movement. In Milan, it is possible to see at the Pinacoteca di Brera Rissa in galleria (1910), in the Gallery of Modern Art there is Ragazza che corre sul balcone (1912) by Giacomo Balla, and finally, in the Museo del Novecento there are Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913) by Boccioni, his States of Mind and other Futurist works by Carlo Carrà.

In Rovereto it is possible to visit the museum dedicated to the work of Fortunato Depero, in what was his art house, while stillin Italy, other works by the Futurists can be found in Venice, where one can admire Severini’s Dancer in Blue (1912) and Carrà’s Interventionist Manifestation (1914) in the Gianni Mattioli collection at the Peggy Guggenheim, and in Turin, in the Galleria civica dì’arte moderna, where some of Balla’s Iridescent Compenetrations dated 1912 and 1913 are housed. Other works by the Futurists are part of private collections located throughout Italy.

Abroad, numerous works are in the MOMA - Museum of Modern Art in New York, and among them are Balla’s Lampada ad arco (1911), La città che sale (1910-11), La risata (1911), a different version of Stati d’animo: Farewells, States of Mind: Those Who Go, States of Mind: Those Who Stay (1911) and Dynamism of a Foot-baller (1913) by Boccioni, and Funeral of the Anarchist Galli (1911) by Carrà. Finally, in the Centre Georges Pompidous one can see Balla’s The Planet Mercury Passes in Front of the Sun (1914).

|

| Futurism: origins, development and main exponents of the avant-garde movement |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.