The topic of female patronage has begun to appear in the field of art history studies in recent years. In the field of gender studies, there has recently been a flourishing of research that has largely focused on women artists, and at most a few pioneering monographic studies have focused on the best-known patrons (such as Isabella d’Este, for example): contributions of great significance, often unpublished, and capable of significantly changing our perception of art and society in the past, but that of women patrons is a field still largely to be explored. It tended to be the case that in ancient societies women’s exercise of power had even heavy limitations (and the relationship between women and power in ancient times is also a substantially new field of study: it will be worth mentioning, in this case, the conference Women of Power in the Renaissance, edited by Letizia Arcangeli and Susanna Peyronel, held in Milan in 2008, one of the first opportunities forin-depth study of the subject, albeit limited to a single century), but in the field of arts and letters women enjoyed greater freedom, with the result that many of the places we visit today in the great cities of art, or in smaller towns, are due to a lively female patronage.

Tuscany, from this point of view, constitutes a particularly happy example, having known, throughout its history, the presence of numerous patrons who have enriched this land with works, even capital works for the history of art, but of which we tend to forget the name of those who ordered them. A very recent (Nov. 7, 2023) international workshop entitled The Patronage of Medici Princesses in the European Context: Comparing Traditions and Identities, edited by Sabine Frommel and Elisa Acanfora, which set out to study the extent of Medici patronage for women, and to understand how this activity was embedded, more generally, in the framework of the political relations of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany at the time: “The princesses,” we read in the project’s introduction, “were surrounded by a circle of ambitious nobles, endowed with a refined culture: it is sufficient to mention the Tuscan outcasts in France and the fundamental role of the Gondi, who in turn promoted cultural strategies capable of bringing forth new artistic syntheses.” The aim of the project was also to “consider the comparison with the patronage promoted by their husbands, fathers, brothers or sons, laying the groundwork for the reconstruction of a profile, including a psychological one, of the protagonists, ranging from adherence to emulation and ’aversion,” in anticipation of results that can "elucidate the development of the artistic culture of the Medici, built on continuous exchange, a va et vient involving new criteria in a game that sees the action of the donor and the beneficiary alternating in a vast platform of migration."

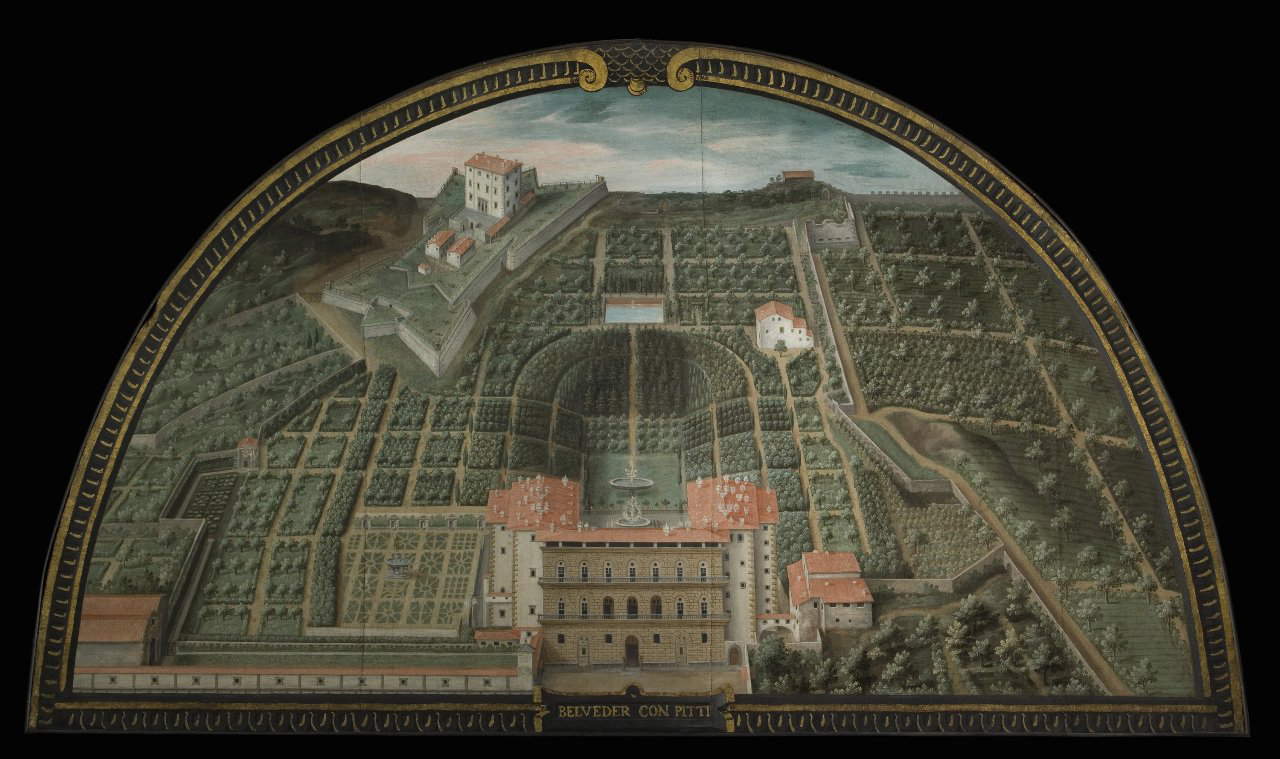

Here we will limit ourselves to a quick excursus on female patronage in Tuscany from the sixteenth to the early twentieth century by examining some of the most eminent figures, starting with one woman, Eleonora di Toledo, whose patronage can be considered almost in competition with that of her husband, the duke (and later grand duke) Cosimo I de’ Medici. The year 2022 was, we might say, the year of Eleonora of Toledo, since it marked the five hundredth anniversary of the birth of the noblewoman Leonora Álvarez de Toledo y Osorio (Alba de Tormes, 1522 - Pisa, 1562), and a major exhibition at the Pitti Palace traced a comprehensive profile of her, not forgetting, of course, her cultural activities as well. We owe to Eleanor of Toledo the creation of the Boboli Gardens and its ornamentation, what Bruce Edelstein, an art historian who has devoted part of his studies precisely to the duchess and who curated the major Florentine exhibition, calls “the greatest work of patronage in the artistic-architectural sphere attributable to Eleanor of Toledo.” We then owe to Eleanor the commissioning of numerous works of art, beyond the well-known official portraits (the most famous being the Portrait of Eleanor of Toledo with her son Giovanni, a masterpiece by Bronzino preserved in the Uffizi, but the duchess nevertheless played a decisive role inimporting to Florence the effigies of the court’s children, a custom first attested at the Habsburgs and later introduced at the Medici court precisely through Eleanor), tending on the one hand to exalt her own rule (think, for example, of the cycle of the tapestries of the seasons, executed by the workshops of Jan Rost and Nicolas Karcher on cartoons by Francesco Bacchiacca), and on the other to transform the taste of the time. Eleanor was thus a direct patron of works of art (out of all it would suffice to mention the frescoes of Eleanor’s Quarter in the Palazzo Vecchio), but also an innovative trend setter (her presence in Florence determined substantial changes even in thesphere of fashion, since in those years the severe tastes of republican Florence were being abandoned and a period oriented instead toward the colorful and luxurious fashion that looked to Spain, the duchess’ homeland), as well as a protector of letters: it should be noted, in the latter sphere, that dedicated to her, among others, are the Rime di Tullia d’Aragona, which is perhaps the first work in the history of Italian literature written by and dedicated to a woman.

Other women who entered the house of Medici because of matrimonial policies, as well as refined patrons, though less studied and less known than Eleanor of Toledo, are Christina of Lorraine (Bar-le-Duc, 1565 - Florence, 1637) and Maria Magdalena of Austria (Graz, 1589 - Passau, 1631): the former became grand duchess consort in 1589, a year after marrying Ferdinand I de’ Medici (son of Cosimo I), while the latter, Cristina’s daughter-in-law having married her son Cosimo II, became grand duchess consort in 1609 (Cristina, moreover, was also co-regent of the grand duchy between 1621 and 1628). To Christina of Lorraine we owe, among other undertakings, the decoration of the Villa La Petraia, which had been assigned to her after her marriage to Ferdinand I: just as Eleonora di Toledo had called Bronzino to fresco her apartment in the Palazzo Vecchio, Christina also called some of the leading artists of the time to decorate the rooms of the villa (Bernardino Poccetti frescoed the private chapel, while Cosimo Daddi devoted himself to the cycle with the undertakings of Christina of Lorraine’s ancestors). A recent study by German art historian Christina Strunck, devoted precisely to Christina of Lorraine, has speculated that the Grand Duchess’ influence is responsible for the plan of the Chapel of the Princes in San Lorenzo, which would be inspired by the rotunda of the Valois family in the basilica of Saint-Denis, just just as, according to Strunck, it would be Christina of Lorraine, and not her husband Ferdinand, who commissioned the decorations of the Sala di Bona in the Pitti Palace, one of the most sumptuous rooms in the Medici palace, which, moreover, was only recently reopened. We know, moreover, that Christina of Lorraine was interested in science: she was the recipient of a famous 1615 letter from Galileo Galilei on the relationship between scientific knowledge and religious zeal, through which the great scientist not only expressed his position (Galileo advocated the need for the independence of scientific research from sacred texts) but also sought the Grand Duchess’s protection in view of the foreseeable trouble his theories would bring him.

By contrast, the perhaps even lesser-known name of Maria Magdalena of Austria is linked to the Medici Villa at Poggio Imperiale, where the grand duchess, sister of Emperor Ferdinand II of Habsburg, settled in 1618: it was she who commissioned the architect Giulio Parigi to restore the building, and it was from her that the villa took its name (“Poggio Imperiale” in homage to Magdalene of Austria’s origins). In addition, Maria Maddalena commissioned one of the leading artists of the time, Matteo Rosselli, to decorate the villa’s interior: it is interesting to note that she entrusted him not only with a cycle on themes related to her lineage, but also with a series of paintings featuring biblical heroines. A woman, then, who intended to celebrate the virtue and valor of women through one of the cycles that would remain among the pinnacles of seventeenth-century Florence. And again Maria Magdalena of Austria initiated, between 1625 and 1627, one of the most admirable artistic endeavors of the early 17th century in Florence, namely the decoration of the Sala della Stufa in the Pitti Palace, which was later finished after her death. Here, wrote scholar Elisa Acanfora, author of a study that has partly lifted Maria Magdalena of Austria from the prejudices of past historiography (the grand duchess, for example, had a reputation as a bigoted woman but at the same time a lover of luxury and pleasures), the grand duchess “followed partially the embellishment project begun with the enlargement of the palace desired by Cosimo II and entrusted to the court architect Giulio Parigi,” taking a close interest in the work on the Sala della Stufa, whose subjects reflected the literary production that was being promoted in Florence in those very years by Maria Magdalena of Austria herself. The Sala della Stufa also stood as an enterprise capable of entering the political debate of the time: at a time when discussions had reopened on the best form of government and the primacy of monarchy, “the constant reminder of one’s lineage”, Acanfora writes referring to the themes of the decorative cycle (Matteo Cinganelli, Matteo Rosselli and Ottavio Vannini painted there images of great sovereigns of ancient times united with allegorical figures), “is in fact, and in the first place, the reference to an absolute form of government, of which by birth she felt herself the depositary. From a theoretical point of view, in the comparison with ancient monarchies, in Florence as elsewhere, the legitimization of such power was sought. And in the vault of the Stanza della Stufa Maria Maddalena also offered an early and eloquent figurative representation of such ideas.”

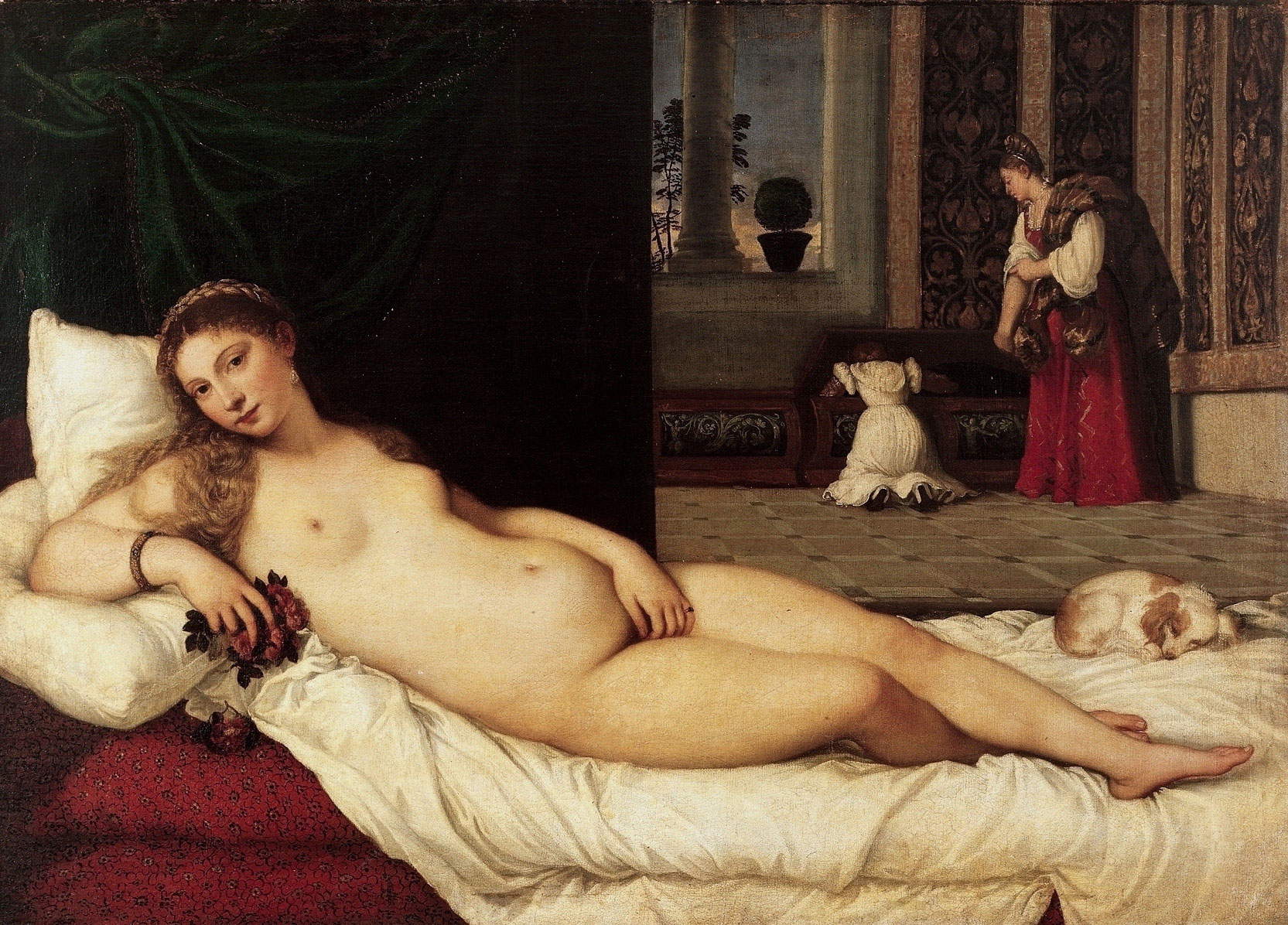

The Marche-born Vittoria della Rovere (Pesaro, 1622 - Pisa, 1694), wife of Ferdinando II de’ Medici, also continued the work of the women who had preceded her in the role of grand duchess consort. Vittoria della Rovere is remembered mainly for being the last heir of the main branch of the Della Rovere family, which died out with her passing, and for bringing to Florence, for that reason, a good part of the admirable collections of the dukes of Urbino, inherited with the passing of her grandfather Francesco Maria della Rovere in 1631: it is for this reason that today we find in the Uffizi masterpieces such as Titian’s Venus of Urb ino, the diptych of portraits of the dukes of Urbino by Piero della Francesca, the Portrait of a Young Man with an Apple attributed to Raphael, and several others. Vittoria della Rovere is also known for having been an attentive supporter of music, for having carried out the decoration of the Sala della Stufa (it was with her that Pietro da Cortona was called in to decorate the walls with scenes of the Four Ages of Man, a masterpiece of Baroque painting), for having commissioned Baldassarre Franceschini known as the Volterrano to paint the frescoes of thewinter apartment of the Pitti Palace, for enlarging the palace itself after the death of her husband, and for being a generous supporter of the Istituto della Quiete, the headquarters of the lay congregation of the “Minimal Handmaids of the Incarnation” founded in 1645 by Eleonora Ramírez de Montalvo, an educator and poetess who in 1650 had purchased, thanks precisely to Vittoria’s mediation, the Villa La Quiete, which thus became an institute for the education of young Florentine noblewomen.

In the last years of the Medici grand duchy, the work of Violante Beatrice of B avaria (Munich, 1673 - Florence, 1731), wife of Ferdinand de’ Medici, heir to the Florentine throne but never became grand duke as he died before his father Cosimo III, was also distinguished: “a cultured, polyglot, musically versed woman,” as scholar Silvia Benassai writes, “she was attracted to Arcadian circles to which she adhered under the name Elmira Telea, protected literati and poets including Giovan Battista Fagiuoli and the celebrated Sienese Bernardino Perfetti, and was herself endowed with a fluent pen that enabled her to write her own autobiographical portrait in 1693.” Her role as a patron was expressed mainly in her private life: she was, in particular, passionate about goldsmithing and jewelry (it was she, for example, who commissioned from the goldsmiths Giovanni Comparini and Giuseppe Vanni the Crown of Santa Maria Maddalena de’ Pazzi), but there were also numerous painters in her service.

The last great patron of the house of Medici, on the other hand, was Anna Maria Luisa de’ Medici (Florence, 1667 - 1743), daughter of Cosimo III, who exercised her passion for the arts mainly in Germany, in Düsseldorf, having become in 1690 the wife of John Charles William I, prince-elector of the Palatinate: it is, however, thanks to this noblewoman that today we can still admire in Florence the masterpieces assembled along centuries of collecting by her household. In 1737, in fact, Anna Maria Luisa, in the meantime returned to Florence after her husband’s death in 1716, inherited from the last Grand Duke of Tuscany, Gian Gastone de’ Medici, her brother, the family’s immense collection: with the disappearance of the last male heir of the lineage, who died childless and thus destined the main branch of the Medici to extinction, the problem of succession to the grand ducal throne had opened. Anna Maria Luisa harbored the fear that at her passing the considerable artistic treasure accumulated by the Medici over the centuries would be dispersed as had happened on similar occasions. Shortly before Gian Gastone’s passing, the Lorraines had been designated as the Medici successors to the government of Florence, and Anna Maria Luisa had managed to enter into the so-called “Family Pact” with the Franco-Austrian house, an agreement by which the last Medici s’pledged to cede to her brother’s successors the entire patrimony of her dynasty (“Furniture, Effects and Rarities of the succession of the Most Serene Grand Duke his brother, such as Galleries, Paintings, Statues, Libraries, Jewels and other precious things, as the Holy Relics and Reliquaries, and their Ornaments of the Chapel of the Royal Palace.” so we read in the third article of the convention signed by Anna Maria Luisa and Francis Stephen of Lorraine on October 31, 1737), on the condition that “nothing of it shall be transported, or lifted out of the Capital, and of the State of the Grand Duchy.” Modern motivations: Anna Maria Luisa, believing in fact that the patrimony had purposes of “ornament of the State,” “utility to the public,” and “attracting the curiosity of foreigners,” had ceded the entire patrimony with the specific stipulation that all Medici works of art not be taken out of Tuscany. This is also why every year, on February 18, the anniversary of Anna Maria Luisa’s death, the city administration of Florence officially commemorates her.

Next to the women of the house of Medici it is then possible to count, especially in more recent times, some interesting cases of women patrons to whom we owe important works that we still admire in museums, the birth of masterpieces of literature, support for music and various art forms. Without going into the merits of the patronage of women’s monasteries (it should be recorded, however, that convents were, for centuries, important centers of artistic production run by enlightened abbesses who knew and appreciated art, and also promoted, albeit within smaller dimensions, a feminine art such as that of the nun-painter Plautilla Nelli, also frequently studied in recent times), it is possible to mention some women who, although representing sporadic cases, shaped the face of Tuscan culture: one can begin with Carlotta Lenzoni de ’ Medici (Florence, 1786 - 1859), an exponent of a cadet branch of the Medici (the one known as “di Lungarno”), known for having animated, in her palace in Piazza Santa Croce in Florence, a circle of artists, men of letters and intellectuals who oriented significantly the Florentine culture of the early part of the 19th century (among the personalities who frequented her house it is possible to mention Giacomo Leopardi, among others), and also known for her great passion for art. Among the works she purchased it is possible to include Pietro Tenerani’s first important masterpiece, the abandoned Psyche, a work that she bought in 1819 and that contributed to the start of the great sculptor from Carrara’s success: today the Psyche is part of the holdings of the Modern Art Gallery of Palazzo Pitti, to which it came after Carlotta’s death by her express will.

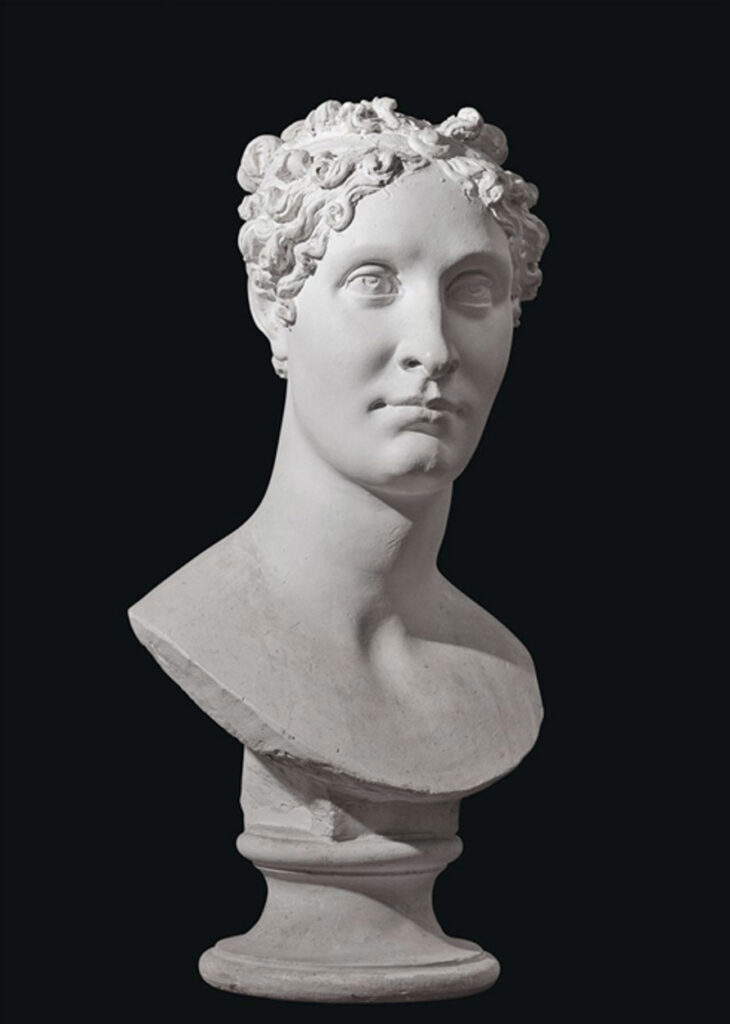

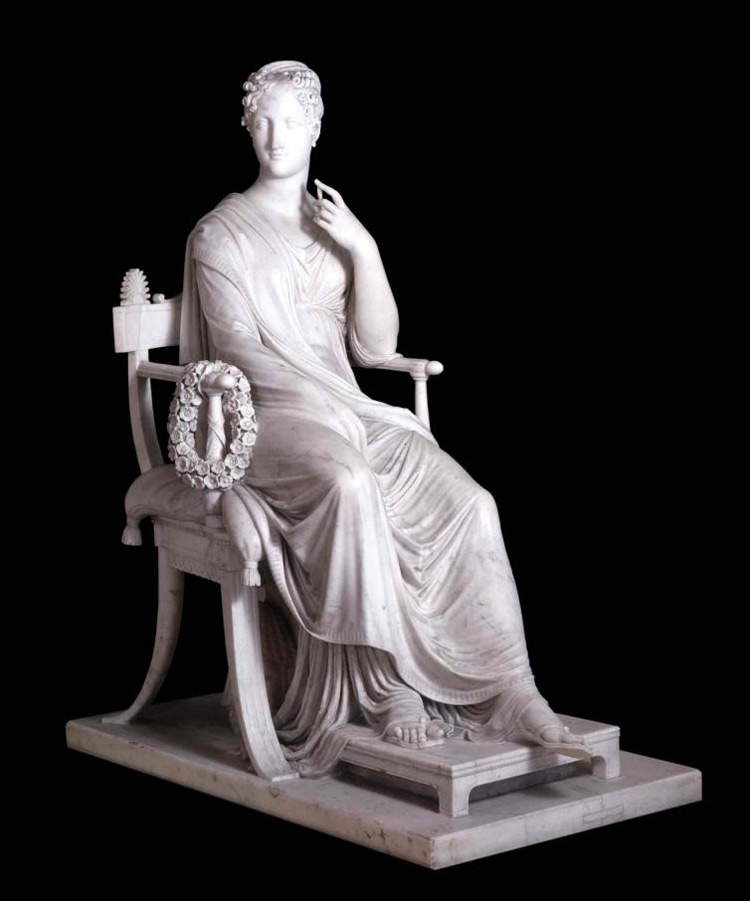

Also dating back to the early 19th century is the patronage of Elisa Bacciocchi (Elisa Bonaparte; Ajaccio, 1777 - Villa Vicentina, 1820), Napoleon’s sister, who in 1797 married Corsican captain Felice Baciocchi and later, in 1805, became at her brother’s behest princess of Lucca and Piombino. In particular, the relationship the princess had with Antonio Canova, from whom Elisa commissioned several works, the most famous of which is probably the Musa Polimnia, which, however, the artist never had a chance to deliver to her since at the time of the fall of the Napoleonic regime the work was not yet complete (the sculpture would later take the road to Vienna), is well known. One is then reminded of the role Elisa played in promoting art, and sculpture in particular, in Carrara, a town that had become part of the principality of Lucca. It was she who, in 1810, assigned the Carrara Academy of Fine Arts its present location, the Palazzo del Principe, and it was she, in a singular operation somewhere between patronage and propaganda, who opened a factory in the town for the mass production of portraits of Napoleon and his family that were to reach all corners of the empire. Elisa evidently liked to portray herself as a cultured supporter of the arts: in 1812, the year Canova stayed in Florence to execute a portrait of �?lisa, the princess commissioned the painter Pietro Benvenuti to paint a large canvas depicting �?lisa Baciocchi together with the sculptor and her husband (depicted discussing together around the bust depicting the princess), surrounded by her court, amidst artists (there can be recognized thecarver and medallist Giovanni Antonio Santarelli, engraver Raffaello Morghen, and painter Salomon Guillaume Counis, all artists to whom she had entrusted commissions and works), and painted seated on a throne in the guise of an inspiring muse.

Elisa Baciocchi’s name is linked to that of the Villa Reale of Marlia, a sumptuous mansion on the outskirts of Lucca where the princess fixed her suburban residence: it was she who transformed the face of the villa, giving the building, transformed in the neoclassical style, and the enormous park surrounding it the appearance that still distinguishes them today. The villa itself became the site of her patronage activities, especially in the field of music, since the villa’s lush veranda theater was often the place where the best artists of the time were called to perform. When the Napoleonic regime fell, after a period of decline, the villa was purchased in 1923 by Count Cecil Blunt, on the advice of his wife, Anna Laetitia Pecci (Rome, 1885 - Marlia, 1971), better known as Mimì Pecci-Blunt, the last patron of this review.

The

The

With her, the Villa Reale of Marlia came back to life: she restored the mansion to the appearance it had had under Elisa Baciocchi by recovering part of the original furnishings that had meanwhile gone missing; she animated an intellectual circle that saw the presence of artists and men of letters such as Giuseppe Ungaretti, Alberto Moravia, Salvador Dalí, Jean Cocteau and Paul Valéry; she used to organize sumptuous parties for which the countess did not hesitate to have special ephemeral settings created. She also amassed an important art collection that included paintings by the greatest artists of her time, from De Chirico to Severini, Mafai to Guttuso, Tozzi to Cagli, and which was located, however, not in Marlia, but in the halls of the counts’ Roman palace in Piazza Aracoeli. In Marlia, however, the vast ethnographic collection has remained, reflecting another passion of Mimì Pecci-Blunt, that for the traditions of the peoples of the world: in the rooms of the Palazzina dell’Orologio, therefore, one can observe the hundreds of puppets dressed according to the customs of the different countries of the world, which the countess commissioned specifically for her own collection, and then again her books, records and much more. All remained in the villa and can be seen today by the public who visit it.

Stories of great women who have enriched the region’s heritage, and without whom Tuscany today would not have the face we all know, stories that are often little known or little explored but that we can imagine will open a new, flourishing season of studies: research on female patronage in history is only just beginning.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.