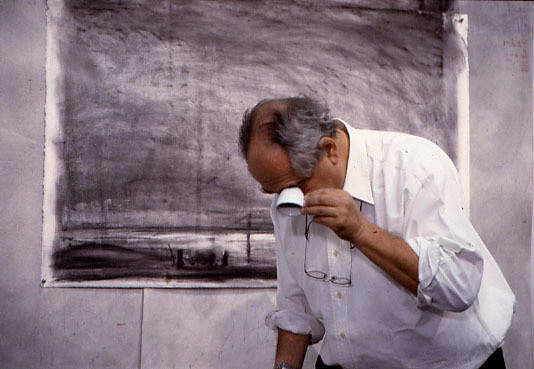

The work of William Kentridge (Johannesburg, 1955) is rich in references. Cinema, literature, visual art, theater but also social, historical and political issues make up his universe. In fact, his artistic practice is the result of a varied training that can be traced through what the artist himself recounts as his “biography of failures.” In interviews, Kentridge reveals of his gradual “surrender” to the idea of being an artist, after trying a variety of paths. When he was three years old, fantasizing about what he wanted to be when he grew up, he had no doubts: an elephant. This anecdote, persistently reported by the artist, already reveals a characteristic of his work and person: a strong self-deprecating charge. At the age of fifteen he dreamed of conducting an orchestra but quickly desisted after becoming aware of the necessarycourse of study. He then graduated in political science and African studies (1976) from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, the hometown he never abandoned. Close to art, particularly drawing, and theater from a very young age, Kentridge attended the Johannesburg Art Foundation between 1976 and 1978. There he experimented, with poor results, with painting, considered by him at the time the expressive medium par excellence, perhaps in a stereotypical identification between artist and painter. He then decided to turn definitively to the theater, studying at the école Jacques Lecoq in Paris. He then abandons the stage in a few weeks. He also tries the film route but, in his thirties, is ultimately reduced to being an artist (the interview Reduced to being an artist, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, also takes its title from this condition).

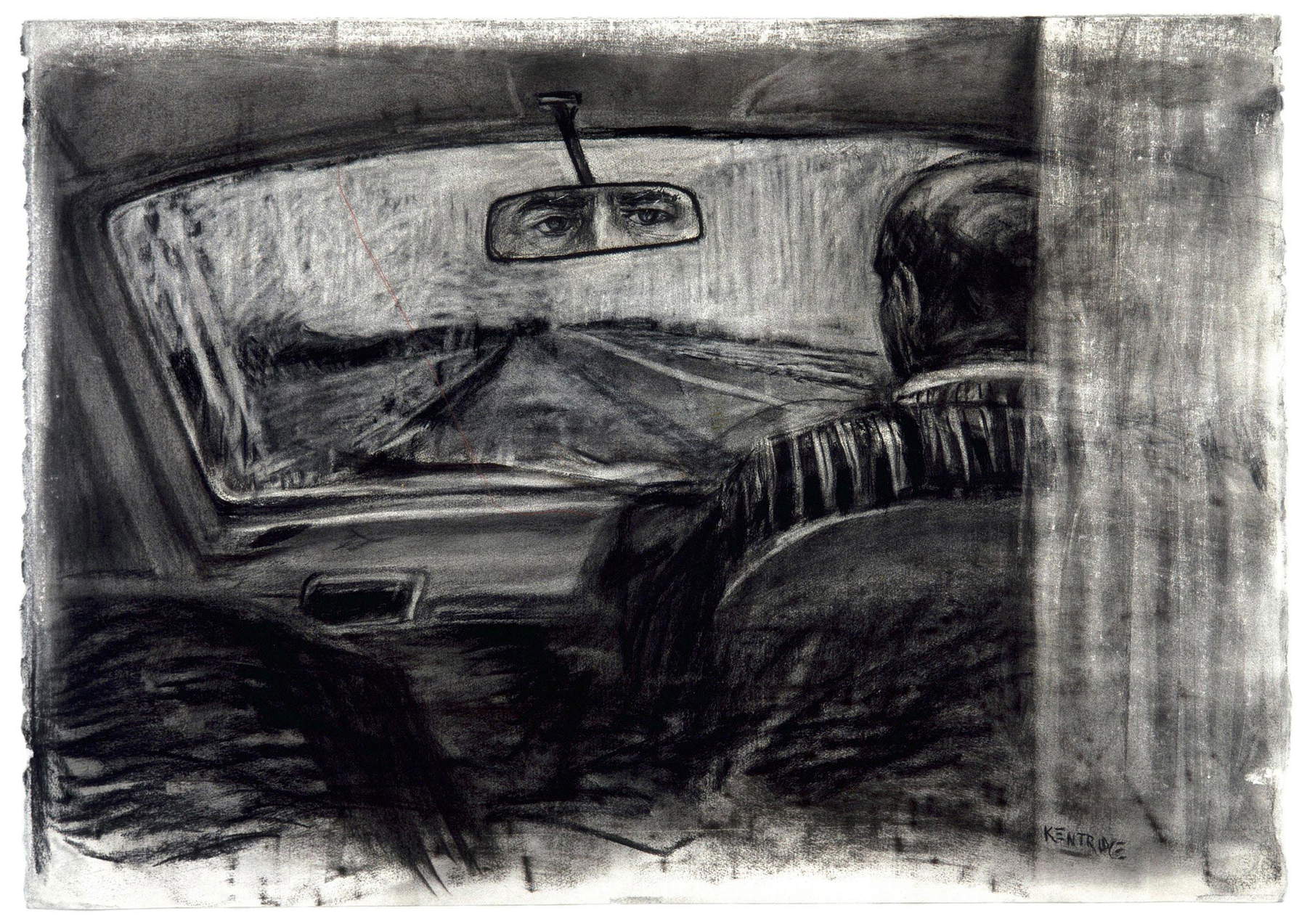

The sources of inspiration for his works (prints, sculptures, tapestries, performances, theatrical productions, animations) are manifold and feed on the autobiographical experiences of the artist, who grew up in a family of white lawyers heavily involved in the struggle againstapartheid, which, as is well known, until the 1990s had disenfranchised South Africa’s black population to the benefit of the white minority. Strong experiences that are echoed in his work, explicitly indebted to the lessons of the slightly younger South African Dumile Feni (Worcester, 1942 - New York, 1991). The latter, among the most prominent South African artists of the 20th century, is the author of African Guernica (1967), a reworking of Picasso’s 1937 masterpiece. His figurative work constitutes a kind of visual commentary on apartheid politics from the perspective of black people. From him, Kentridge inherits the strong stroke and a very reduced use of color, in a black and white universe that welcomes blue or red in some circumstances.

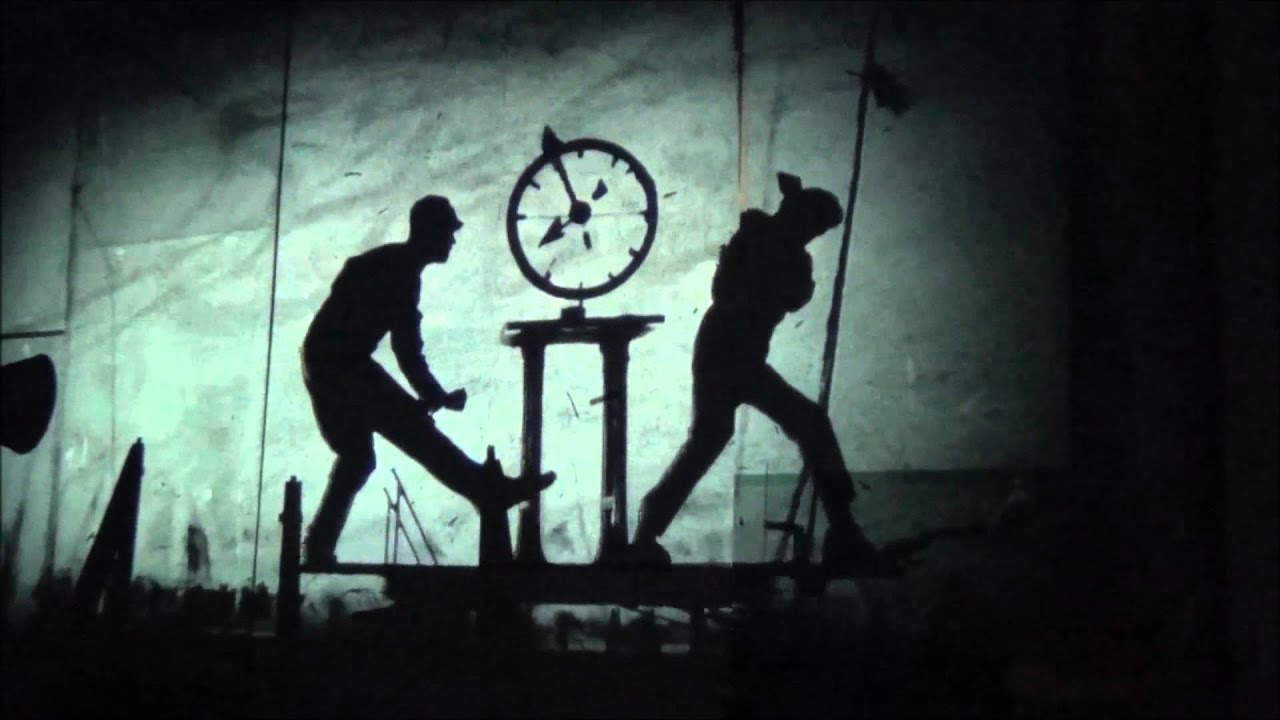

As mentioned, Kentridge’s wide-ranging training naturally leads his research toward a hybridization of different techniques and different genres that can interpenetrate, merge and increase their expressive potential. The point of departure remains the drawing from which the artist draws elaborate animated films that proceed through the concatenation of different scenes that are not established a priori, in a process of continuous erasure and modification of stories by images. Indeed, one of the fundamental characteristics of Kentridge’s work is uncertainty. Within this category the artist sets different modes of operation of the creative process. The choice of charcoal as the preferred medium is due precisely to its possibility of being easily erased, leaving shading on the support. This procedure would allow to ideally follow the unfolding of a thought, not always linear and defined, which from the artist’s mind finds concreteness on the sheet. The choice of not having a precise storyboard at the base of the animated films also responds to the need to accommodate the concept of randomness within artistic production. For the artist, after all, this is precisely how we are able to give a reading to the irrational world around us, constructing memory with sometimes distorted narratives in a continuous process of writing, partial erasure and rewriting. The practice thus adopted gives the work a strong temporal, subjective and impulsive dimension. In this regard, the complex installation The refusal of time (2012) seems to fully restore Kentridge’s feeling that the very concept of time is not to be understood as a unidirectional continuous line. The work, which is accompanied by the theatrical perfomance Refuse the hour (2012), introduces some elements dear to early cinema and the experimental theater proposed by the avant-garde movements of the early 20th century to visually imagine and hypothesize the auroral period of research that later led to the publication of Einstein’s theory of relativity in 1905.

|

| Dumile Feni, African Guernica (1967; charcoal on newsprint, 226 x 118 cm; Alice, University of Fort Hare) |

|

| William Kentridge, The refusal of time (2012; five-channel video installation, duration 30’) |

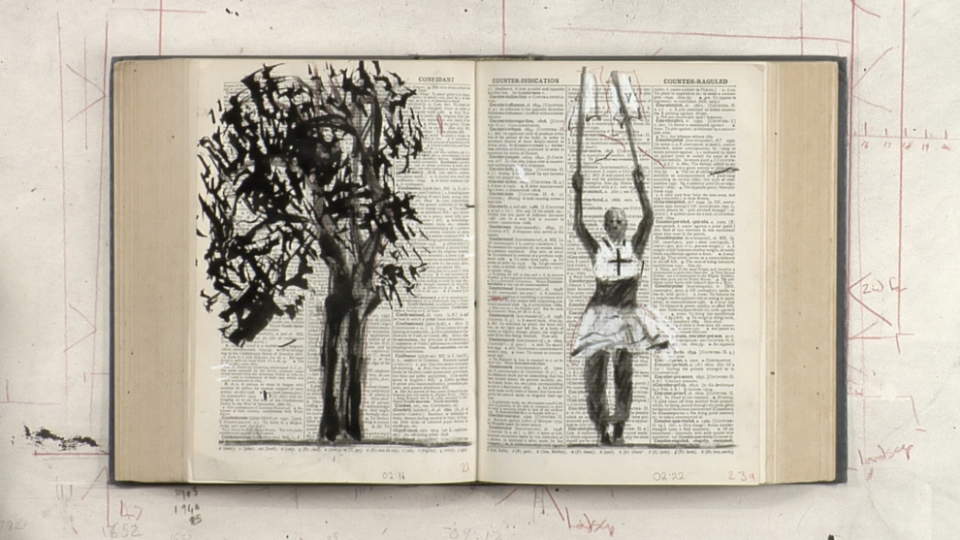

Thematically, the works move between a fantastical imagery and a more historical and political one. In the first category can be included works such as Journey to the moon (2003) in which the artist witnesses the transformation of a coffee cup into a telescope with which he can explore the universe. Even the coffee pot loses its traditional function and takes off, like a spaceship, for the moon. The space co ffeemaker ends up stuck on the earthly satellite in a quotation from Georges Méliès’ famous Le voyage dans le Lune (1902), also paid homage in the series 7 fragments for Georges Méliès (2003). Like the early film classic, Kentridge’s lunar voyage is also recorded inside the artist’s studio, a place of creation par excellence. This emblematic microcosm represents for Kentridge a kind of extension of his mind, as he explains in the short film directed by Rosa Beiroa, The mind of an artist (2018). The studio is also the space in which Kentridge experiences a constant division of the self, assuming from time to time the role of creator and viewer of the works. The artist’s splitting also occurs within the works, where his self-portraits appear on several occasions. This is the case in Second-Hand Reading (2013). In the video work, Kentridge’s hand begins to leaf through an encyclopedia. Within it, landscapes, animals, and human figures drawn by the artist overlap the pages and come to life. The drawings also include the artist’s silhouette as she pensively traverses the volume, page after page.

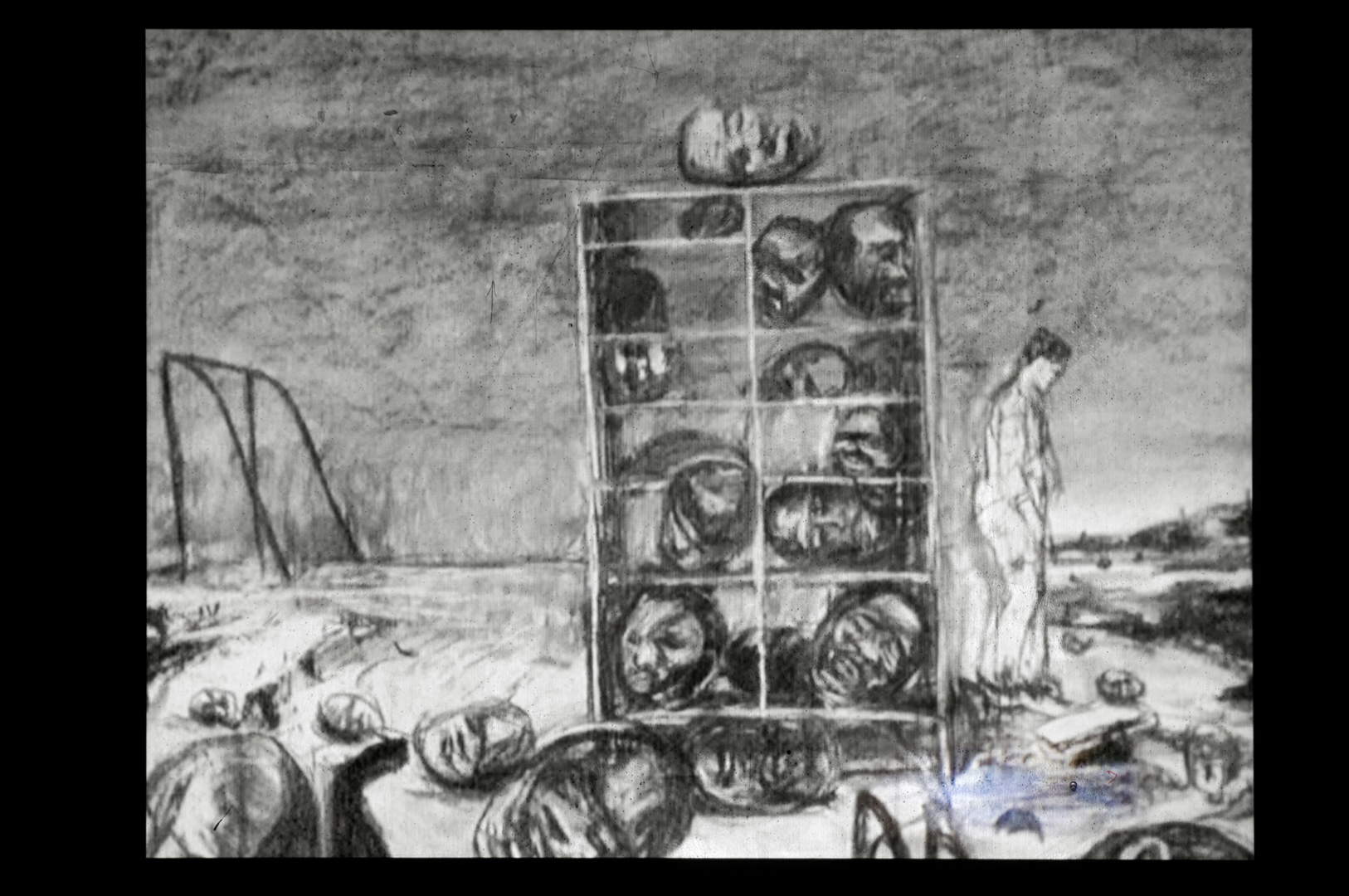

On the historical vein, a cycle of animations introduces two fictional characters who move against the backdrop of Johannesburg between the 1980s and 1990s. Soho Eckstein is a cold white real estate developer concerned only with his business. His alter ego, a more positive character, is Felix Teitelbaum. The two appear in Johannesburg, 2nd greatest city after Paris (1989) on exploited land, an extremely barren landscape. Next to them, in Eckstein’s office, rows of faceless African miners stream by until in the finale Felix discovers several of their severed heads. The scene brings to mind an experience the artist had when, at an early age, he came across violent photos of massacres, available to his lawyer father. With this ironically titled work, Kentridge denounces exploitation in South Africa, reflects on colonialism and capitalism, and alludes to inhumane policies present far beyond African borders in the Western world.

|

| William Kentridge, Journey to the moon (2003; 35 and 16mm film transferred to video, duration 7’10"; New York, MoMA) |

|

| Georges Méliès’sLe voyage dans le Lune (1902). |

|

| William Kentridge, 7 Fragments for Georges Méliès (2003; 7 video projections, black and white, silent; Rivoli, Castello di Rivoli) |

|

| William Kentridge, Secondhand Reading (2013; Beijing, UCCA Center for Contemporary Art) |

|

| William Kentridge, Johannesburg - Second greatest city after Paris (1989; 16 mm film; Los Angeles, The Broad) |

A few years later, Felix in Exile (1994) introduces a new character. An African woman, Nandi, starts the animation by drawing the still bleak African landscape and showing the bodies of some wounded people on the ground. Felix, already present in previous works, is in exile, and from a room he follows Nandi’s story. The two meet through the mirror, thanks to a spyglass that puts them in contact, until the woman is struck and dissolves like the other wounded bodies. Water then invades the space where Felix is, in allusion to weeping and pain but also to the idea of a new rebirth. Kentridge raises the question of the historical memory of the colonial past and the redefinition of a national identity based on remembrance rather than erasure. In another installment of this series, History of the Main Complaint (1996), it is precisely the memory and consciousness of Soho Eckstein that is investigated. From a hospital bed, the comatose man traverses in thought the violence perpetrated on black Africans and instantly receives those same wounds of theirs on his body. Soho awakens and returns to work without the viewer being given to know whether the hospitalization has also led to moral redemption. The play fits historically into the years of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, a body established in 1995 to reconstruct the crimes of apartheid and lead the country toward democracy.

The constant confrontation with history is also an element present in Triumphs and Laments (2016), the large frieze created on the banks of the Tiber River in Rome. The work is conceived as a kind of “graffiti in negative” with an ephemeral nature, destined to disappear with time. Kentridge does not add matter but, through hydropolishing, makes some monumental figures emerge from the smog and dirt deposited on the wall. They trace the glories and defeats of the city from ancient to contemporary times. In about 500 meters, Kentridge ideally invites almost a hundred figures to a walk along the river, proposing unprecedented rereadings of history and placing side by side, among others, Marcus Aurelius, Mussolini, Romulus and Remus, Pasolini, Michelangelo, Victor Emmanuel, the Capitoline She-wolf and many others who would hardly, by chronology, have been able to meet.

|

| William Kentridge, Felix in exile (1994; 35mm film transferred to video, color, sound, duration 8’43"; New York, MoMA) |

|

| William Kentridge, History of the main complaint (1996; 35mm film transferred to video, black and white, sound, duration 5’50; London, Tate Modern) |

|

| William Kentridge, Triumphs and Laments (2016; Rome, Lungotevere) |

Similarly, Kentridge himself has been likened to illustrious artists such as Albrecht Dürer and Rembrandt by Iwona Blazwick, director of the Whitechapel Gallery, a major London institution where the South African exhibited in 2016. At the age of sixty-six, the artist is officially recognized among the contemporary masters, heir to the expressionist graphic language of George Grosz, Otto Dix and Max Beckmann but also to the Dada spirit. Kentridge, with “an invention of extraordinary magnitude,” as Renato Barilli calls it in his survey of art before and after 2000, animates his charcoal creations and experiments with a mode of expression “rich in artistic coefficients in the fullest sense” (Renato Barilli, Before and After 2000. Artistic Research 1970-2005, Feltrinelli Editore, Milan, pp. 198-200). With the collaboration of various professionals (composers, costume designers, sound and lighting technicians, performers), the South African artist gives life to a complex universe that is fully recognizable yet unpredictable and all to be investigated in its multiple suggestions.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.