Wilhelm Brasse, the Auschwitz photographer who saved tens of thousands of images

Photographing all the prisoners arriving at the Auschwitz concentration and extermination camp: this was the task of Wilhelm Brasse, still remembered today as the “Auschwitz photographer.” Three photos for each prisoner, and while he was shooting, Wilhelm already knew their sad fate. Of death, of suffering, of atrocities. Men, women, children, the elderly passed in front of his camera, unaware of what would happen to them, of their lives being broken, of their futures being lost. Frightened, tired faces, marked by suffering and fear.

He was also interned in the camp, but given his skills as a photographer he found himself witnessing and “collaborating” with the Nazi system in the Auschwitz camp, forced to photograph all the prisoners to make identifications easier for the camp leadership. Could he have refused? Perhaps he could have, but he knew full well that his refusal would lead him to certain death; out of an instinct for survival he accepted the assignment, but he made the choice by saving tens of thousands of photographs at the time of the liberation of the camp, the80th anniversary of which marks this year. In fact, all his work constituted a valuable record of all the atrocities that took place in the Auschwitz death camp and an invaluable aid to the trials of Nazi war criminals.

Born on December 3, 1917, in Żywiec, Poland, his father was of Austrian descent, while his mother was Polish. From his teenage years, Wilhelm developed a deep passion for photography, spending much time in the photography studio owned by an aunt in Katowice, where he began to learn the secrets of the craft. His life changed dramatically with the Nazi invasion of Poland. Because of his Austrian ancestry on his father’s side, the occupying authorities repeatedly tried to persuade him to join their armed forces, subjecting him to constant pressure, but Brasse steadfastly resisted and refused any form of collaboration with the regime. Tensions increased to the point that Wilhelm decided to flee Poland for France, but his plan failed. He was caught on the Hungarian border during the escape attempt and imprisoned. During his detention, the Nazis continued to try to recruit him into the Nazi army, but he steadfastly maintained his refusal. His decision not to join led him in 1940 to be repeatedly interrogated by the Gestapo and finally deported to the Auschwitz concentration and extermination camp, which had recently been opened. He was registered under the number 3444. At Auschwitz, he was initially treated like all other prisoners: subjected to forced labor and extreme living conditions, but then the camera saved him from death. In fact, he was recruited by the camp commandant, Rudolf Höss, to photograph the prisoners as they gradually arrived at the camp; he was chosen to work in the photo lab run by the Gestapo inside the complex, in Block 26 of Auschwitz I.

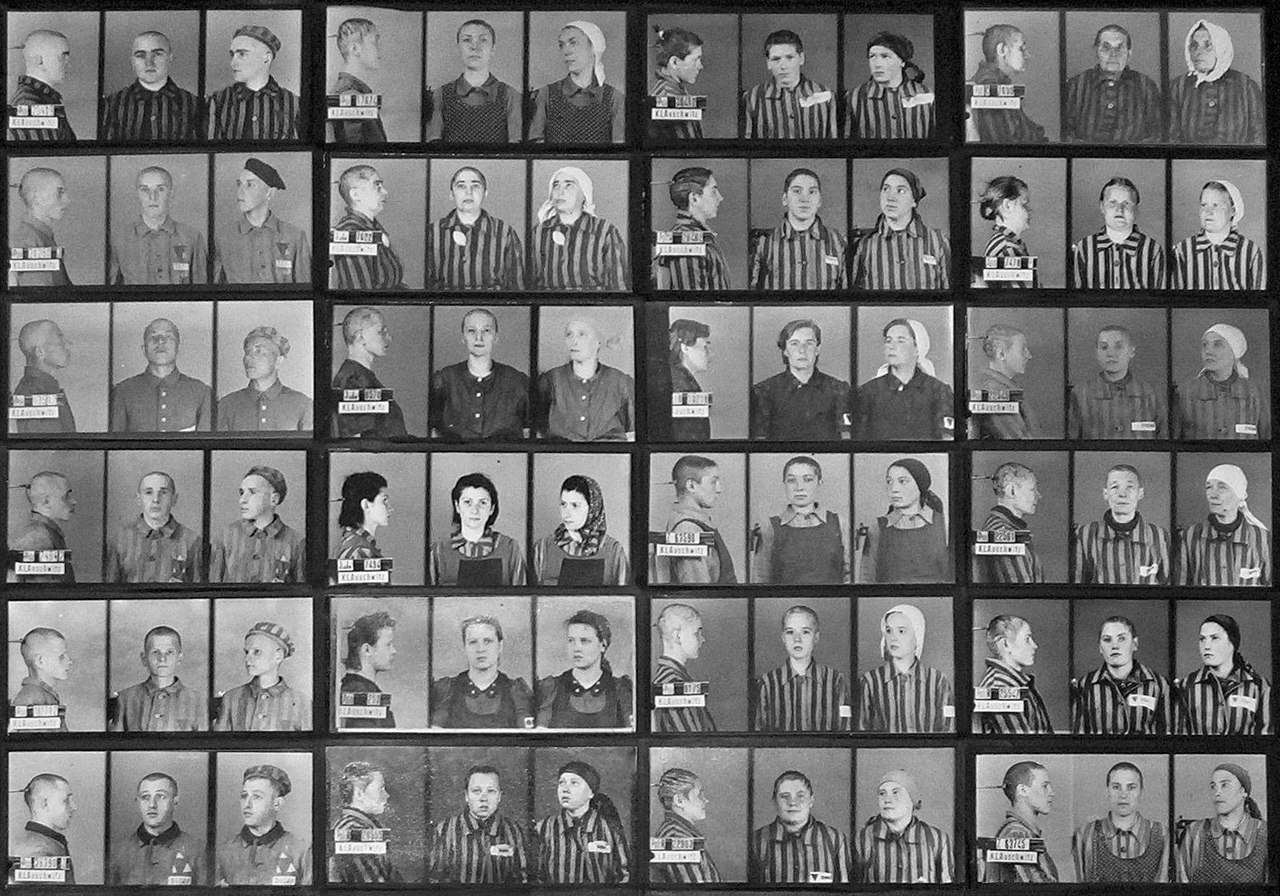

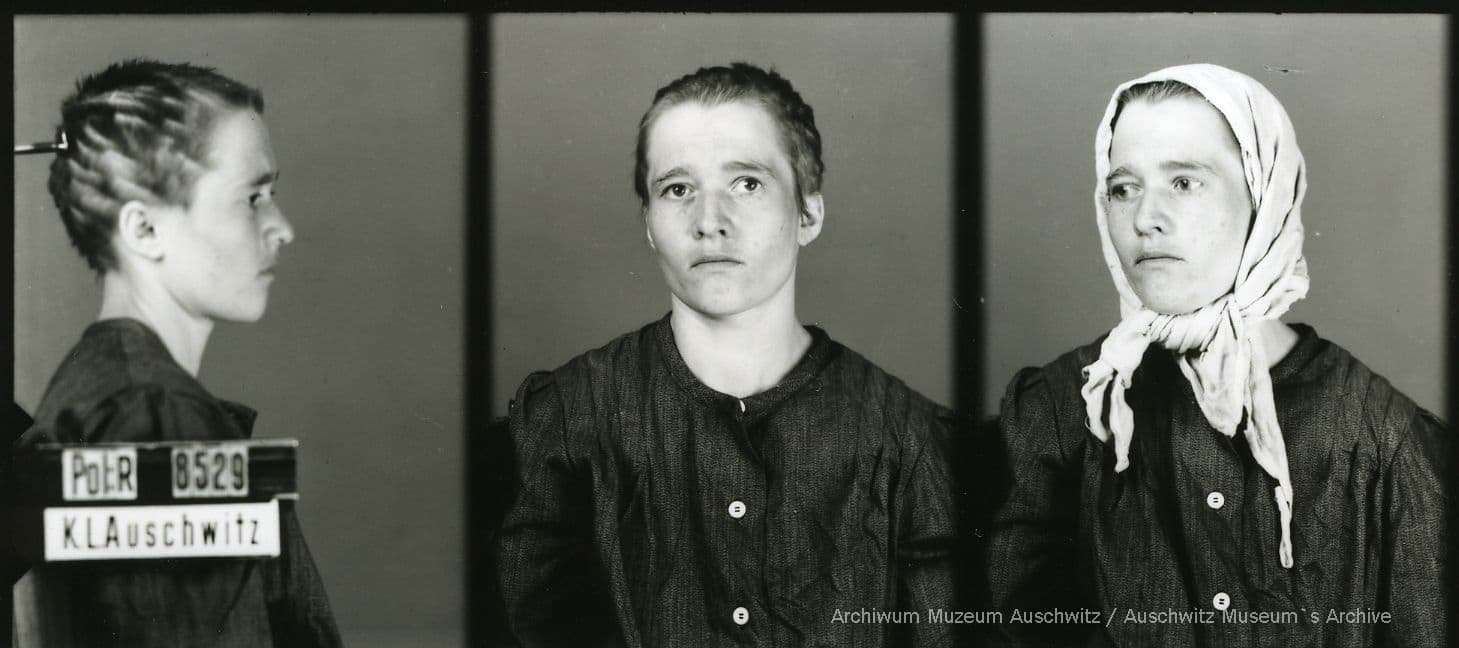

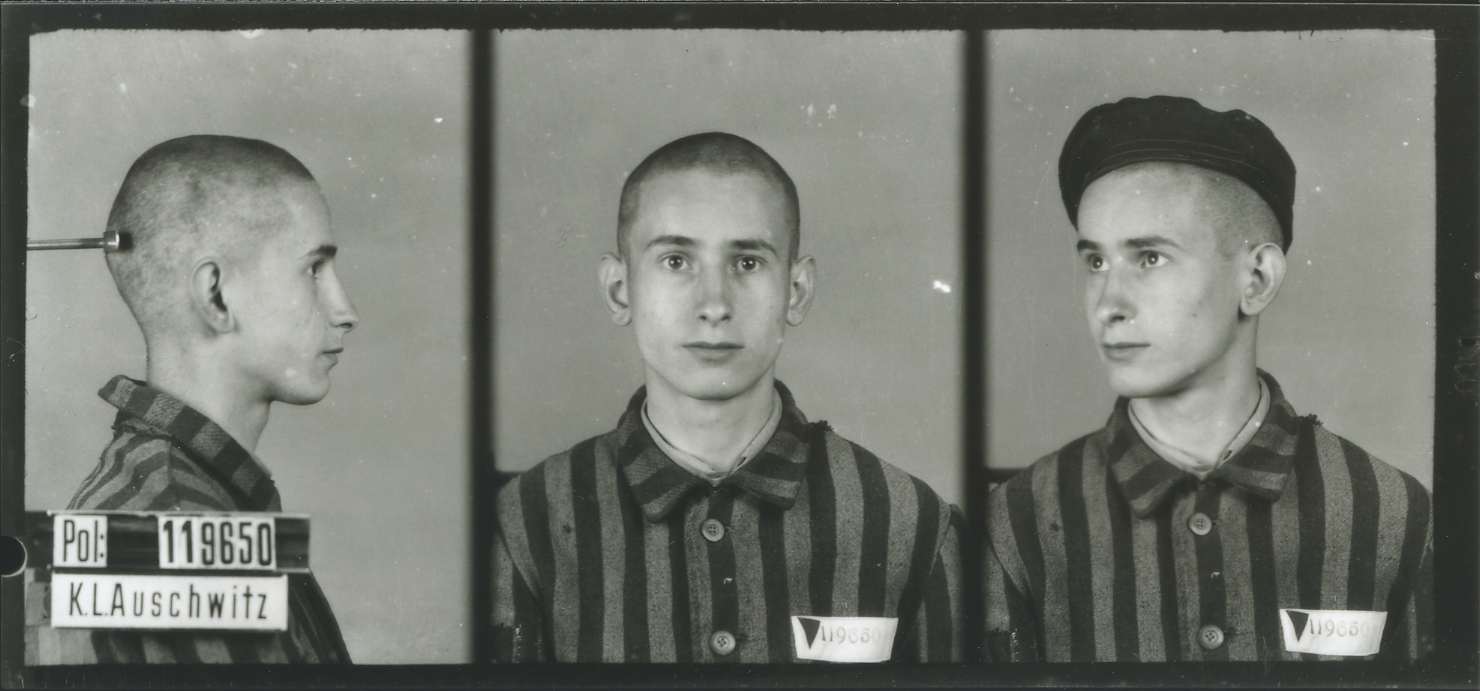

Prisoners were summoned to the photo lab through the Häftlingsschreibstube, the prisoners’ administrative office. Before being photographed, they had to comply with a series of strict procedures: prisoners were obliged to have their hair shaved and to sew clearly on their prisoner-striped uniforms the identification number and a triangle that, depending on the color, indicated the reason for their imprisonment. It was also mandatory to wear headgear. At the appointed time, the prisoners were arranged in an orderly line in front of Block 26, following the ascending numerical order, so as to facilitate the photographers’ work. Each prisoner was photographed in three standard poses: in profile, bare-faced in front, and in front wearing headgear (men) or a shawl (women). In the lower left corner of each photograph were the identification number, nationality and the designation “KL Auschwitz” (short for Konzentrationslager Auschwitz). This strict system was intended to document and catalog, in a ruthlessly bureaucratic manner, every prisoner in the camp.

Among his duties Brasse also found himself, following his encounter with Dr. Josef Mengele, the Nazi criminal doctor called the “Doctor Death,” documenting medical experiments conducted on prisoners treated as human guinea pigs. For Wilhelm, the knowledge that all the prisoners immortalized by his photographs were destined for certain death turned each shot into a torture. Each image told a fragment of daily horror: brutally beaten, consumed by disease and mistreatment, reduced to walking skeletons, their faces scarred by the terror and violence they endured. His lens was forced to document an inhuman reality, and he a silent witness to a nightmare that would haunt him for the rest of his life.

Wilhelm Brasse, together with Bronisław Jureczek, another prisoner working in the Auschwitz photo lab, played a crucial role in saving so many of these photographs. In January 1945, as theRed Army approached, the two were ordered to destroy all photographic documentation. The task was supervised by Bernhard Walter, the head of theErkennungsdienst, the photographic identification department. While carrying out the order, Brasse and Jureczek put wet photographic paper and large quantities of photographs and negatives into the furnace. Such a large amount of material would prevent the smoke from escaping. Once the furnace was lit, they thought that this way only a few photographs would burn and then the fire without oxygen would go out. Pretending to be in a hurry, they scattered some around the rooms of the laboratory: during the evacuation, in the rush, no one would have time to take everything and so something would be saved. Before finally leaving the building, the two finally closed the laboratory door with wooden boards to prevent access. Thanks to this action 38,916 photographs were saved.

After the camp was liberated by Allied forces, the recovered photographic material was placed in bags and, according to the account of Józef Dziura, a former prisoner, was delivered to a photographer in Chorzów. Later, the material was taken to a Polish Red Cross office in Krakow. In 1947, the photographs were finally transferred to the archives of the newly established Auschwitz-Birkenau Nazi concentration camp museum in Oświęcim.

The process of describing and cataloguing this documentation was entrusted to Karol Rydecki, also a former camp prisoner, who worked in the museum’s Mechanical Documentation Department. During his work, Rydecki noted on the back of the photographs, using pencil or ink, information such as the prisoners’ names, dates and places of birth, dates of arrival at the camp, and dates of death. Thanks to these annotations, the photographs became not only a visual record of the horror of Auschwitz, but also a valuable historical source.

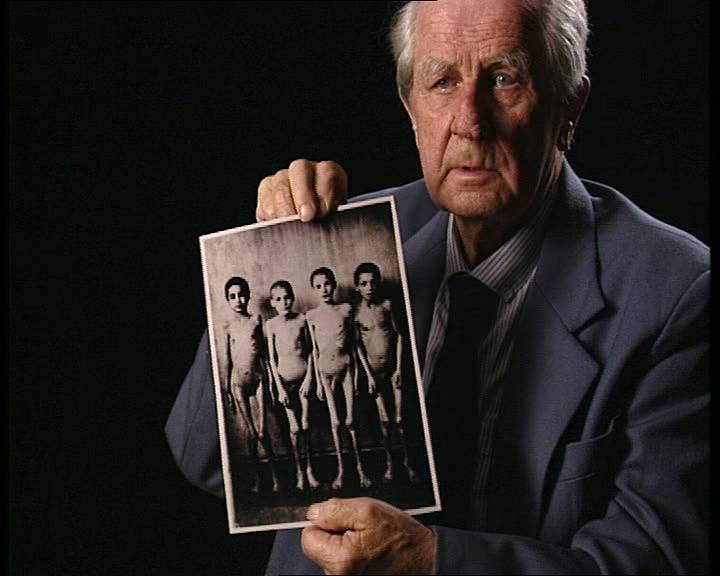

What about Brasse? After the Liberation, once he returned home to Żywiec, where he was born, he was unable to take any more photographs. “Although I had a Kodak camera, I could no longer take pictures, I was repelled by them,” he confessed years later. In the last years of his life, he decided to tell his story publicly, contributing to the historical memory of the Holocaust. In the Polish documentary film The Portraitist(Portrecista), directed by Irek Dobrowolski and produced by Anna Dobrowolska in 2005 and first broadcast on Polish television TVP1 on January 1, 2006, he recounted not only his work in the concentration camp and the moral burden he had to bear, but also the stories behind some of the pictures he had taken himself. These included the story of Czesława Kwoka, fourteen years old and Polish like himself, who was deported together with her mother to the Auschwitz camp and killed with a phenol injection in March 1943, a month after her mother. In the triple photo that has become famous, Czesława is wearing her striped uniform, in one even with a shawl on her head, over her short hair that had just been forced to be cut, as camp rules required. Next to her number, attached to her uniform, is a red triangle marking her as a political prisoner. There are also signs of violence on her lips: according to Brasse’s testimony, just before the photos she was beaten by one of the supervisors because, confused by the orders she received and by the language she did not know, she did not understand what she was supposed to do. So the woman vented her anger against the innocent girl. “She cried, but could do nothing. Before the photograph was taken, the girl wiped the tears and blood from the cut on her lip. To tell the truth, I felt as if I had been hit myself, but I could not interfere. It would have been fatal. You couldn’t say anything at all,” Brasse recounted in the documentary.

The story of Wilhelm Brasse, who died in 2012, at the age of 94, was also told in a book, The Auschwitz Photographer, written by Luca Crippa and Maurizio Onnis, published in 2013 by Piemme. Five years of life in the camp, over fifty thousand shots. Visual testimonies that give insight into the reality of Auschwitz and the atrocities of the Holocaust. So that through images and memory we will always continue to remember.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.