Why we suffer so much from the fascination of ruins

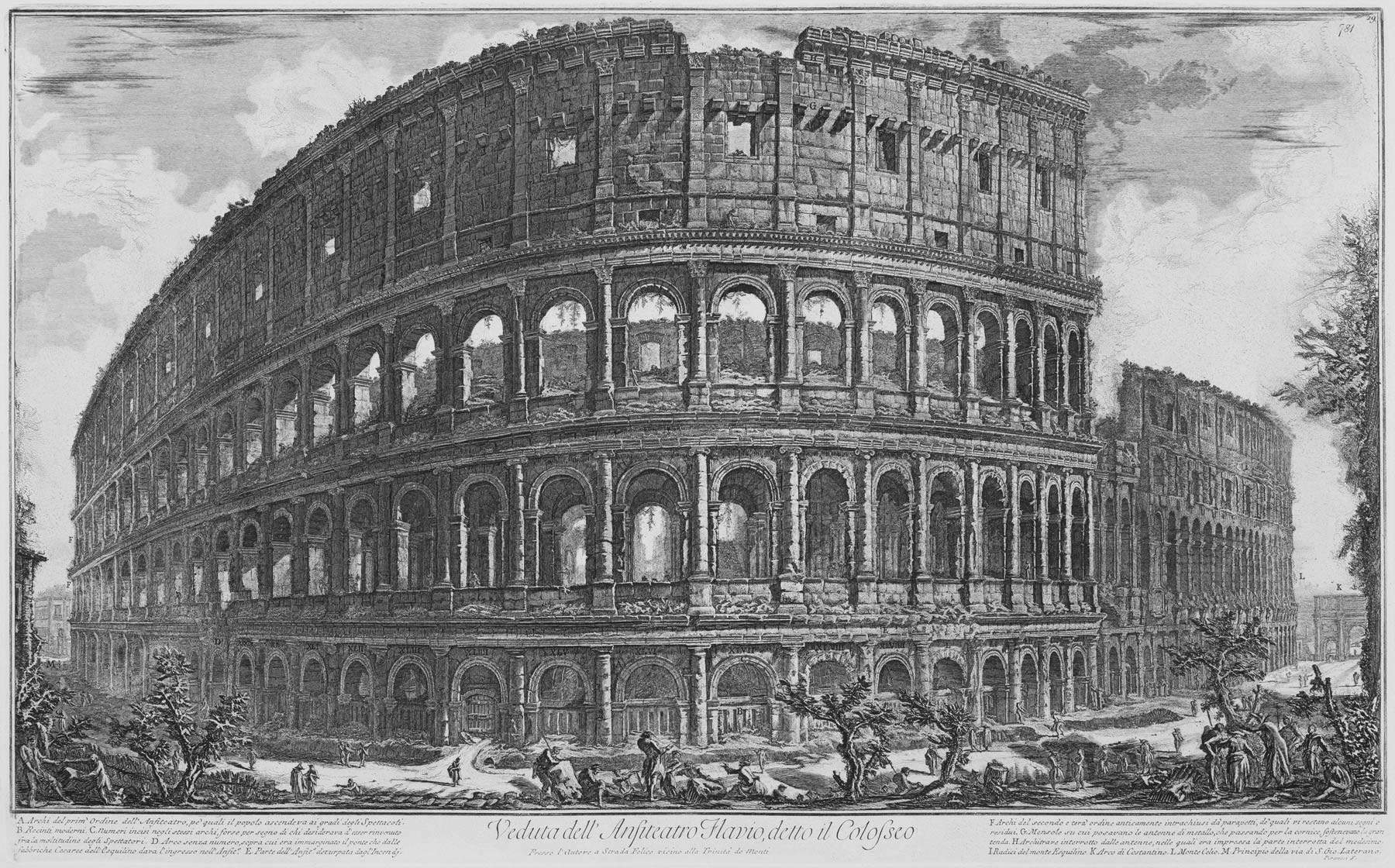

They came from all over Europe. From England, from Germany, from France, from Flanders, from Holland. Finished the plains of the Rhine, past the tangle of the Black Forest, past the Jura massif, before the eyes of the travelers opened the imposing and menacing spectacle of the Alps. In the heart’s desire to see Italy, the soul consumed by the anxiety of arriving at the eternal Urbe. Someone had read Goethe, who had finished that journey a few years earlier and had recounted it. Almost everyone had in mind the images of Giambattista Piranesi, the artist who perhaps more than others helped to fuel the imagination of eighteenth-century travelers, to shape that fascination with ruins that moved the yearnings of those who set out on their Grand Tour toward southern Europe, toward the splendors of Florence, toward the ruins of Rome, Paestum, Agrigento, toward the temples of Greece. Piranesi’s Views of Rome , the successful series of engravings begun by the Venetian artist around 1747, sold singly or in fascicles, had been instrumental in forming that sense of attraction to ruins. Piranesi’s Rome was a city that mixed nostalgia for the grandeur of the ancients with a sense of an unstoppable, devouring modernity, alive in the facades of the palaces and villas that engulfed the vestiges of the ancient city. It was a city teeming with an assorted and busy humanity wandering among the ruins of temples, great bath complexes, and centers of power. An indolent and bewitching Rome, whore and vestal, magnificent in its decline, magnified by its storyteller’s sense of the sublime who offered travelers the image of a grand and terrible city. An image that would end up disappointing Goethe, once he came face to face with reality and was free to indulge his frustration in theItalienische Reise: “the ruins of the baths of Antoninus and Caracalla, reproduced by Piranesi with rather fantastic effects, could not satisfy us at all, up close, the eye accustomed to those reproductions.”

Piranesi was certainly a lover so taken with the image of his beloved that he offered an unfaithful reading of it (as all lovers do, after all), but of that “so beautiful unfaithfulness” that he liked “infinitely,” as Giovanni Ludovico Bianconi would recognize, who already at the beginning of the nineteenth century had posed the problem of whether Piranesi’s “warmth” corresponded to the truth. It was precisely that infidelity, however, that would condition the imagination of Grand Tour travelers. And of artists, of course: the ruins of ancient Rome (and ancient Italy, in general) populated the paintings of the greats of the eighteenth century. Canaletto’s whimsy mixing real views and ruins, Giovanni Paolo Panini’s ideal views, Hubert Robert’s picturesque ones, Joseph Wright of Derby’s gloomy Neapolitan landscapes, and then Bernardo Bellotto, Antonio Joli, Abraham-Louis-Rodolphe Ducros, John Robert Cozens, Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller. Not forgetting all those painters who were asked to fix on a canvas the memory of a journey, and that memory almost always substantiated in the view of a ruined temple. The list is endless. There were also those who had their portraits painted, in front of the ruins: Pompeo Batoni was a specialist in the genre, and he lived a long life painting portrait-souvenirs of the young nobles who wanted to bring back to their lands the memory of those remains. We would be wrong, however, if we thought that the seduction of ruins was a sentiment that marked one century more than another.

The eighteenth century, the time of the Grand Tour and the sublime, is just the century that we most easily and most commonly associate with fascination for ruins, because this feeling is one of the most characteristic elements of the aesthetics of those years, because it is theepoch in which the first regular, systematic archaeological excavations began, conducted with an attitude that we would call scientific, because never before had the passion for the vestiges of the past crept into the works of artists in such a pervasive way, because never had ruins themselves been the subject of a work of art. And if we think of Füssli’s masterpiece, the Artist’s Despair before the Greatness of the Past, we might add that never before had any artist tried to express that emotion with such convincing emotion. Yet, the fascination with ruins is a passion that pervades the history of Western civilization.

In the Epistulae ad familiares is preserved a strong and poetic letter from Servius Sulpicius to Cicero, in which the great orator’s friend, in order to console him for the death of his daughter Tullia, tells him of a trip he made to the ruins of Aegina, Megara, Corinth, “all cities once flourishing with life, which now lie before our eyes demolished and crumbling.” Sulpicius tells Cicero that the sight of those ruins had been a relief to him in a moment of despair: “we lowly beings despair if any of us have died or been killed, while in one place lie toppled the dead bodies of so many cities.” The sight of those cities in rubble induces Sulpicius to stop, to think, to reason about the transience of life. Centuries later, the Mirabilia Urbis Romae, which came into being before the thirteenth century, a kind of guide to the monuments of ancient Rome for pilgrims on their way to the Eternal City, concludes by noting that “many temples of palaces of emperors, consuls, senators, prefects were in this city in the time of the pagans, as we read in the ancient annals, as we have seen with our own eyes and as we have heard from the ancients. We took care to report, as best we could in writing, for the memory of posterity, how much beauty there was, how much gold and silver, how much ivory and precious stones.” Later, in the Renaissance, the way of looking at the ruins mirrors, roughly, the feelings expressed by Poggio Bracciolini when he arrived in Rome, in 1430, forced to find how decayed, changed, disfigured was that city “which gave spectacle to the world,” with the plants obscuring what ch’had once been the triumphal street, with the dung of the herds covering the senators’ benches, with the forum that had become an expanse of mud where the peasants brought pigs and buffaloes, in a ruin “made all the more evident by the stupendous remains that have survived the ravages of time and fate.” That idea of a past falling under the blows of the present had, however, served as a spur, had brought about a new attitude toward the ancient, which became a territory to be discovered, to be observed, to be explored: with this idea in mind, in 1402, two young artists, Filippo Brunelleschi and Donatello, had gone together to Rome to see at close quarters that much-desired ancient, to investigate it, to study it.

Then there is a fascination with ruins that knows a very wide spread among contemporary artists. In the art of Anselm Kiefer, ruins, whether those of a rural landscape(Ausbrennen des Landkreises Buchen, 1974), those of the buildings that Albert Speer designed for the Nazi regime(Innenraum, 1981), or those, more ideal than real, of the Venice that was for a thousand years an independent republic(These writings, when they are burned, will finally give some light, 2020-2021) are the most expressive of the vague nihilist substratum that shapes at least part of his work, they allude to the dawn and sunset of civilizations, to the eternal alternation of death and rebirth, of creation, destruction and then creation again, they are the signs, faded and ghostly, of’a history that constantly sets new beginnings but then returns to swallow everything because, Kiefer would say, there is nothing eternal under the sun.

Again, Pierre Huyghe has set Human Mask, his masterpiece, one of his most disturbing works, in the ruins of Fukushima. Mike Nelson’s installations abound with degraded laboratories, gutted buildings swallowed by sand, collapsing walls, abandoned houses (and of course his epigones cannot be counted: the memory of Gian Maria Tosatti’s Italian Pavilion, which at the 2022 Venice Biennale took us inside the corpse of a 1960s factory, is alive). Thomas Hirschhorn has accustomed us to monumental installations that force the visitor to wander among the rubble, physical and symbolic, of our society, inside post-apocalyptic worlds destroyed by wars, natural catastrophes, by a consumerism that ends up consuming itself, collapsing under the weight of what it has produced. In Italy, the artist who works best on the theme is probably Andrea Chiesi: his painting is populated with modern ruins, abandoned architectures that are painted with Renaissance perspective rigor, with clean, lucid, sum neatness, buildings that once pulsed with life and now instead fall apart, are attacked by creepers, become a metaphor for’a critique with political overtones that nevertheless leaves a hope, a possibility of a new life, the idea of an expectation, since each of Chiesi’s ruins is as if traversed by a metaphysical light, irreproducible with the photographic medium.

Here, photography: photography of ruins has now become a genre in its own right. The masters of the genre, from Josef Koudelka to Camilo José Vergara, from Ryuji Miyamoto to Giovanni Chiaramonte, are now followed by swarms of proselytes, faithful, followers, imitators who all over the world are dedicated to ruins photography, and some combine a passion for the camera with a passion for exploration: this has given rise to a very particular hobby, urban exploration, which consists of infiltrating inside abandoned places, often with camera in tow in order to divulge everything via social media, without care of breaking property laws or endangering one’s physical safety, for the sake of snooping around in a hastily abandoned house fifty years ago, in a factory that closed its doors decades ago, in an uncovered country church.

It would be all too easy to consider the fascination with ruins as the most immediate visual translation of nostalgia, which is among the strongest feelings a human being can experience, or as the reflection of’a melancholic temperament that takes pleasure in contemplating the scraps of the past, or as the territory on which to pour some form of restlessness, an indefinable anxiety, the awareness of our precariousness, our fragility. And one cannot motivate this fascination by talking about fear, curiosity, desire, exaltation, because one would move to the level of personal reactions. There are those who consider ruins as documents of the past, and this is true, but it is not enough: a piece of column that we see inside a museum does not seduce us in the same way as a piece of column that we see where that column was erected two thousand years ago. The fascination for ruins is something more powerful: it is an element that characterizes our civilization, it cuts across times and places, it is a feature of our collective memory but it often has to do with the personal history of each of us. Chateaubriand, like Cicero’s friend Sulpicius, ascribed to ruins a consoling power: seeing the past in ruins comforts the human being who reflects on his own littleness, because decay is the darkness into which once powerful men, once flourishing kingdoms, once dominant civilizations have plunged, and no one is able to escape this fate. But even this idea is not sufficient to explain why we suffer so much from the fascination of ruins, although Chateaubriand was among the first to try to provide answers. If anything, the reasons must be sought within the ruins themselves, in their unique condition, which is that of being the product of an encounter and clash between human beings and nature.

Ruins are the only work of man in which we observe the fruit of this dualism. There are, of course, various works in which the human being provides for a more or less extensive intervention of nature, but the ruin is the only one in which there is no form of calculation, no form of domestication. In ruins there is not the balance that lives in a work of art, in an architecture, in a park. The first to intuit this quality of ruins was Georg Simmel: it was 1911 when he published his own original, innovative reading of the fascination with ruins. “The whole historical process of humanity,” he wrote, “constitutes a progressive assertion of the dominion of spirit over nature, which it encounters outside itself but in a certain sense also within itself. [...] At the instant, however, when the decay of the construction destroys the harmony of the whole, the parts separate again and reveal their original universal enmity, as if artistic formation had been nothing more than an act of violence of the spirit to which the stone has reluctantly submitted and now this is gradually ridding itself of this yoke and returning to the autonomous legality of its own forces.” Ruins are the evidence of a nature that by its own force lives and gives shape to a “new totality,” and the fascination that ruins exert on us lies in the idea that a work of thehuman being appears to us to be radically modified by nature, by the same forces that shaped a mountain, a river, a landscape, but it also resides in the upheaval that ruins impose on the hierarchies imposed by our civilization, since “what the spirit had raised,” Simmel wrote again, “becomes the object of those same forces that formed the profile of the mountain and the bank of the river.” It has been said that the ruin is the product of a clash, but also of an encounter, since it forms a unity with the landscape, a unity that is a symbolic metaphor of a reconciliation between different opposites: intention and chance, nature and spirit, past and present, but also near and far, visible and invisible.

Finally, the theme of ruin as a manifestation of a past in the present should be considered, already suggested in nuce, with great modernity, by Simmel himself, and then developed by Marc Augé in recent times. Ruins escape time because they are the sum of different times, they are an ageless place, they are manifestations of a concrete absence and at the same time a living presence. “Ruins,” wrote Marc Augé, “are like art: an invitation to feel time.” They are the place where the present meets the past, the place where a dream collides with its destiny. They may in turn be erased, but they can never be bound to a specific era, caged, claimed. And the idea that ruins are so elusive lives, often unconsciously, in the soul of anyone who observes them. Ruins also fascinate us because, confounding the times they lived in and preserving their mysteries since they are incapable of telling a full story, they open our imagination and communicate to us, more or less consciously, a strong, exciting sense of freedom which is given precisely by the distance between our present and their present, between those who built those buildings and us who watch them being torn apart, between the action of human beings and nature, a distance in which infinite are the stories, the hopes, the possibilities.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.