Why is Gustave Caillebotte not as famous as the other Impressionists?

When thinking of the Impressionists, most tend to enumerate the typical textbook names: Monet, Manet, Renoir, Degas, sometimes Sisley and Pissarro. After all, the painters just mentioned can be considered the masterminds of what is perhaps the best-known artistic current in the entire history of art. However, alongside the leading names, there were also a well-stocked number of artists who, unfortunately or fortunately (depending on one’s point of view), did not end up in thecollective imagination. But that is not to say that they were not equally (and perhaps more) evocative figures than their more famous colleagues. One such artist usually forgotten by the general public is Gustave Caillebotte (1848 - 1894).

Yet Caillebotte was one of the most modern and innovative Impressionists, definitely ahead of his time. Few others, like Caillebotte, in the 1870s understood the importance of the aid that the newly born photography could bring to painting. The result, then, is that Caillebotte’s paintings appear to us as true snapshots of late nineteenth-century Parisian life, or of the country idleness of the wealthy classes (Caillebotte came from a very wealthy family). The painter understood that photography was the best medium for documenting everyday life. And he decided, therefore, to give his paintings a distinctly photographic slant. Subjects often protrude from the edges of the painting, views seem to be outlined by making use of the wide-angle lens, the characters who populate the streets of his Paris appear to us in motion, portrayed in their full naturalness, without filters or poses, and the viewpoints are often unprecedented when not daring: the very views from above, typical of the painter’s style, seem almost to anticipate a type of photography that would emerge only a few decades later.

|

| Gustave Caillebotte, Rainy Day in Paris (1877; Chicago, Art Institute) |

|

| Gustave Caillebotte, Roofs in the Snow (1878; Paris, Musée d’Orsay) |

In addition to these paintings, mention should also be made of works depicting rowers while rowing, typical of Caillebotte’s production. In some of these works, the artist introduced a particular depiction that we can consider to be a forerunner of the modern subjective shot: that is, Caillebotte portrayed rowers and rowers as if he were sitting in front of them on the canoe. All with a very particular technique: probably, Caillebotte was never fully Impressionist, because his style combined elements of academicism, realism and, indeed, Impressionism.

|

| Gustave Caillebotte, Rower with Cylinder (1878; Yerres, Propriété Caillebotte) |

Why, then, was such an innovative artist long forgotten, given that following his demise no one took more interest in his painting, at least until the 1950s? And why does his name still struggle to be juxtaposed with that of the most famous Impressionists? That the artist was talented was well known to his contemporaries. Émile Zola, in his 1880 article Le naturalisme au Salon, said that Caillebotte was “a very scrupulous artist,” “who has the courage to make great efforts and who seeks the most virile solutions.” In 1894, in the aftermath of his death, Camille Pissarro, writing to his son Lucien, said that Caillebotte was a “good and generous person and, what does not hurt, a talented painter.” However, it must also be considered that Caillebotte always carried around that label of garçon r iche (“rich boy”), as Zola himself called him, which caused many to regard him as little more than an amateur, a wealthy scion who could afford to laze around painting. In fact, Caillebotte, as we mentioned earlier, came from a very wealthy family, belonging to the Parisian upper middle class: his father Martial was the head of a business that had operated for generations in textiles for the military, and he had a house in Paris, the one in which Gustave was born, as well as a large estate in Yerres, a country town where the family used to spend their summers (and where Gustave would later return on several occasions to paint his famous rowers). When his father passed away, Gustave inherited, along with his brothers, a large fortune, with which the young man, then 26 years old, decided to subsidize his own activity as an artist.

And, precisely because of his wealth, Caillebotte gave a lot of support to the group of Impressionist painters, of which he was an integral part. He also supported them financially: he bought many of his colleagues’ paintings, managing to amass a sizeable collection (which later flowed into the state collections: many of these works are on display today at the Musée d’Orsay) and even going so far as to pay the rent for Claude Monet’s apartment on the rue Saint-Lazare side of downtown Paris. He became, in short, not only one of the major painters of the group, but also one of its main patrons. And it was precisely because he felt so attached to the group that he did everything he could to keep it united even when disagreements began to undermine its integrity.The attempts failed, however, and the artist, probably disappointed to see that the group’s unity was practically compromised, decided in 1882 to exhibit with the other Impressionists for the last time, in what would be their penultimate exhibition, followed only by the final one in 1886. At the same time, Caillebotte decided to put an abrupt halt to his purchases of paintings and, above all, to hang up his paintbrushes almost completely: until the end of his days he devoted himself to other activities, such as boating, philately and gardening, and returned to fixing his impressions on canvas only on a few occasions, without participating in major exhibitions.

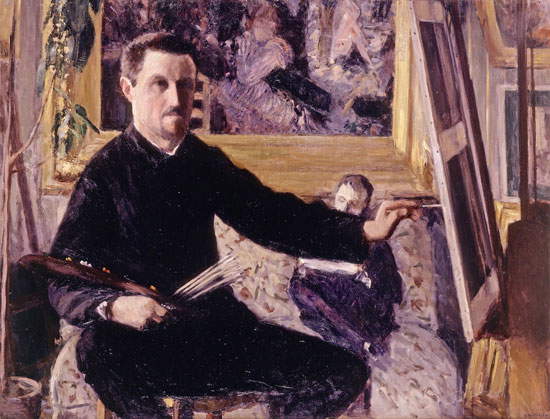

|

| Gustave Caillebotte, Self-Portrait at the Easel (ca. 1880; private collection) |

After his untimely death, his executors enforced his wishes. Indeed, he had written in his will, already drafted in 1876: “I donate to the State the paintings that I possess; however, since I want this gift to be accepted to the extent that the works do not end up in an attic or in a provincial museum, but end up first in the Luxembourg and then in the Louvre, it is necessary that some time elapse before this clause is executed, and that is until the moment when the public will not say that they will understand these works, but at least accept them.” Caillebotte had foreseen well: some members of the Academy of Fine Arts in fact protested against the entry of Impressionist works into state collections, deeming it “an offense against our school.” However, in the end Caillebotte’s wishes were carried out, and for the first time in history a core of Impressionist works (although some had been rejected) became part of a public collection.

Among the 67 works that Caillebotte left to the state, not a single one had been painted by him. This is why, for a long time after his death, Gustave was considered more of an important patron and wealthy collector than a modern and innovative painter in the same league as his friends. His generous gift, in short, had obscured his artistic importance: indeed, it must be added that almost all of his output, after his passing, remained the property of his family (and many works still are), and thus concealed from the eyes of most. This was due to the fact that Gustave, being rich, did not need to sell his paintings. The artist, in short, painted out of pure passion: this fact, however, instead of earning him an excellent reputation, led art historians to underestimate the real scope of his art.

Interest in Gustave Caillebotte began to assert itself from a specific date, 1951, when the Galerie Wildenstein in Paris mounted a first small retrospective of some of his works, actively collaborating with art historian Marie Berhaut, who had been working on the forgotten artist for some years, encouraged in her work also by the Wildenstein family itself. The exhibition constituted, for Marie Berhaut, an opportunity to begin drafting a first catalog raisonné of the artist’s paintings, which was published, after other studies came out in the meantime, in 1978, under the title of Gustave Caillebotte, sa vie et son oeuvre: catalog raisonné des peintures et pastels ("Gustave Caillebotte, his life and work: catalog raisonné des peintures et pastels"). At the same time, probably stimulated by the studies of Marie Berhaut and colleagues, the U.S. art historian Kirk Varnedoe also began to take an interest in Caillebotte: in his early thirties, Varnedoe curated a major monograph on the artist at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in 1976. An exhibition that stopped at the Brooklyn Museum in New York the following year: this was the decisive exhibition for the rediscovery of the artist.

Today, Gustave Caillebotte’s name is among those of the great Impressionists, although, given his background, he still struggles a bit to establish himself with the general public. But it will probably not take long for a figure as remarkable as this great painter to achieve the fame it deserves.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.