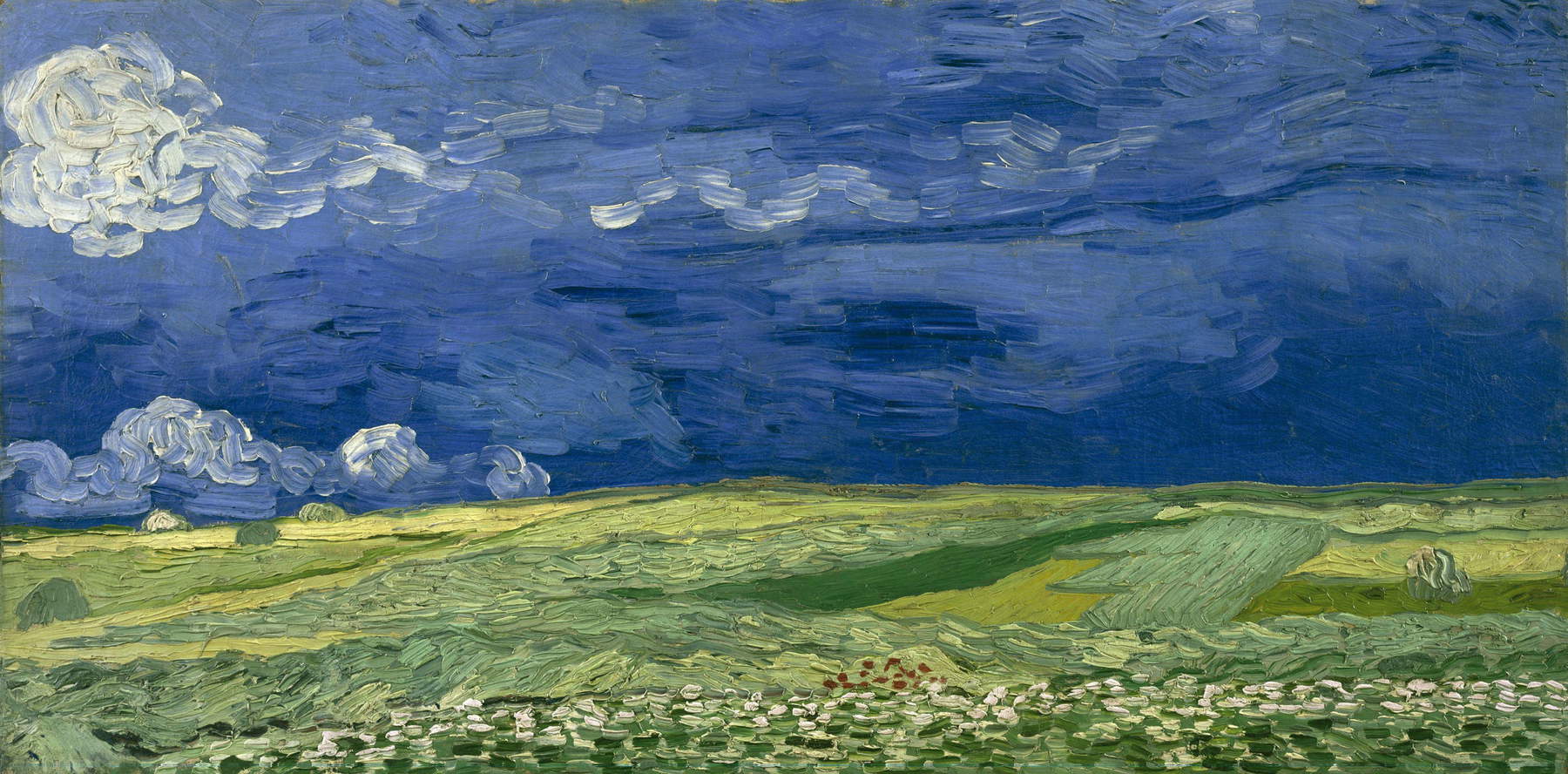

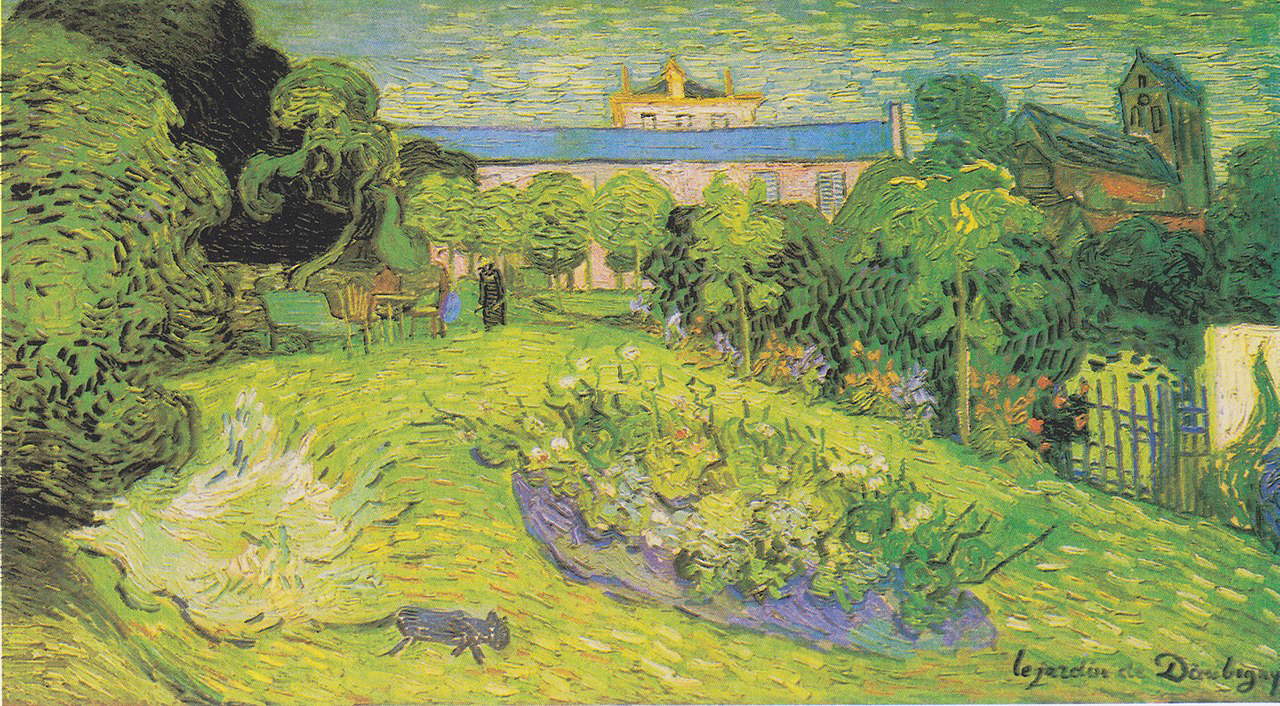

Writing to his brother Theo and sister-in-law Jo in mid-July 1890, a few days before he died, Vincent van Gogh said he had painted three large canvases, three “expanses of wheat fields under turbulent skies,” and said he had painted them trying to load them with feeling, to make them express sadness, extreme loneliness. “These canvases,” Van Gogh wrote, “will tell you what I cannot say in words, what I consider healthy and fortifying about the countryside.” We cannot determine with much accuracy which were the canvases Van Gogh was alluding to, probably Wheatfield under Agitated Skies, Wheatfield with Flight of Crows and The Garden of Daubigny, the first two now in the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, the other in the Kunstmuseum in Basel, but it matters little: more relevant to understanding what Van Gogh meant is the atmosphere of those works than the exact identification. Van Gogh’s extreme works have often been read as overt symptoms, the most obvious manifestations of his mental distress, all the more so since he himself, in his letter to his family members, claimed that he deliberately tried to evoke that sense of sadness that oppressed him, that “storm,” as he called it, that threatened his existence. Perhaps, however, critics have focused too much on the cause and too little on the effect, despite, again, Van Gogh himself providing the key to understanding the reason for those paintings. The view of the countryside, and he declares this to Theo and Jo, had a beneficial effect on him, and the dichotomy between what the artist felt at that moment of his existence and what reassured him is expressed in those paintings on which Van Gogh was working in the last days of his life. The contradiction between the anguish felt by the artist and the “healthy and fortifying” effect of the countryside is only apparent, and the element underlying this ambivalence, it will be seen later, is also one of the reasons why we are still attracted to landscape painting today, as we have been for centuries.

By “landscape,” without going too much into the specifics of a definition that does not put everyone in agreement, we shall mean here everything that is an aspect of the territory, beyond the fact that the view is urban or natural, beyond ideas about the amount of nature that must go into a landscape in order for us to be able to speak of nature, regardless of whether or not it is well-founded to want to include city views in landscape painting, and also regardless of the medium that returns the landscape to us (painting or photography: only painting will be referred to here). Meanwhile, at the basis of our interest in landscape painting is a rift, a violent one, that occurred at a certain point in the history of Western civilization, a rift that Georg Simmel, in his Essays on Landscape, placed at the end of the Middle Ages, when “the individualization of the inner and outer forms of ’existence, the dissolution of original ties and unions into differentiated particular entities [...] made us see landscape in nature for the first time” (it will be appropriate to recall that Simmel, by “landscape,” meant a circumscribed, bounded piece of nature, recomposed within a momentary or lasting horizon). Landscape painting did not exist in antiquity and the Middle Ages because the creation of landscape “required a laceration from the unitary feeling of universal nature.” Whether, on the other hand, a sense of landscape existed even in ancient times has been debated; one could argue about the precise chronology of this laceration, about the exact moment when the idea that human beings had become a unit separate from the infinite totality of nature became common (for this is the point of the question: not when the human being became aware of his separation from the unity of nature, but when this idea became widespread consciousness), but clear is that a landscape painting begins to spread where a consciousness of landscape arises, i.e. theidea of the existence of a place, a “piece of nature,” as Simmel called it (an apparent contradiction, since nature has no parts), separate from the rest, which can be the object of contemplation, description, artistic representation.

It is interesting to note how landscape painting began to spread throughout Europe at the time of the scientific revolution, effectively establishing evidence of a different way of understanding nature, a nature that was found to be analyzable, decomposable, and measurable in all its parts, as opposed to a nature that was pulsating and alive beyond our will to understand and measure its phenomena. There is evidence, however, that landscape painting, even quite widespread, existed as early as the mid-sixteenth century: in 1547, Giorgio Vasari wrote, in a letter to Benedetto Varchi, that “there is no cobbler’s house that todesque countries are not,” that is, there was no cobbler’s house (landscape painting was considered the least noble) that did not have a landscape painting fromnorthern Europe, notably from Flanders or Holland where the genre was born, and just a year later Paolo Pino in Dialogo della Pittura wrote that northern painters “pretend the countries inhabited by them, which by that wildness of theirs make themselves most grateful.” Vasari was probably exaggerating, perhaps the genre’s diffusion was not so widespread, but the fact that the newly born landscape painting generally occupied the last place in the hierarchy of artistic genres provides solar proof of a characteristic that makes it so welcome to us even today, namely its immediacy: Rezio Buscaroli, in his essay La pittura di paesaggio in Italia of 1935, speaking of the birth of landscape painting had defined it as a “democratic” genre, since it was “apt to satisfy every motive of easy and current decoration of interiors of galleries and halls and exteriors of facades, of loggias, with even relative cost”, and because “with a wide field of use before it,” also as a result of the fact that the landscape paintings that were being produced between Flanders and Holland were small in size and were intended for “the small interior.” Indeed: it was toward the end of the sixteenth century that the genre left the tablet or small canvas and entered fresco decoration. One could point to as a shining example the decoration of the Vatican’s Tower of the Winds, which between 1580 and 1582 was frescoed by the brothers Matthijs and Paul Bril, pioneers of the genre, with fantasy views inspired by the landscapes of the Roman countryside: both were specialists in small-scale landscape painting, and both were pioneers of landscape painting as a totally autonomous genre.

One could therefore imagine that, in addition to a philosophical reason, the birth of landscape painting and its wide and lasting success also had social reasons: James S. Snyder, in an essay on the Nordic Renaissance, could not help but observe that the first landscape specialists, beginning with the Flemish Joachim Patinir, who was already expressing himself in the genre at the beginning of the sixteenth century (although, it should be emphasized, it was not yet a totally autonomous landscape painting, since always included the presence of figures drawn from the sacred or mythological repertoire), had begun to get hits by virtue of the gradual loss of importance of religious painting in the north at the time of the Lutheran Reformation (there was a kind of reversal: if before the landscape was relegated to the margins of the depiction of a saint or a sacred episode, from the 16th century the sacred episode shrinks until it almost disappears and takes a back seat, it becomes the tiny pretext for a painting that draws attentionattention more to the setting than to the figures) and by virtue of the imposition of the tastes of a new cohort of patrons who came from the middle class.

Immediacy, ease of access, a large group of painters who had begun to specialize in the genre, works in small formats that could be purchased with decidedly smaller sums than those needed to procure paintings with other subjects: these were the reasons for the success of landscape painting between the 16th and 17th centuries, even before it entered the homes of the Roman and Italian nobility in general, where it was not initially unrelated to celebratory contexts. The examples of Guercino’s landscapes in Casa Pannini (now at the Pinacoteca Civica di Cento), which are among the earliest examples of autonomous landscape painting in Italy, are worth mentioning: the patron, Bartolomeo Pannini, evidently wanted to exalt the prosperity of the lands of Cento by entrusting the painter with a decorative frieze that included views of the Cento countryside and work scenes to decorate his residence. The “Stanza dei Paesi” in the Casino dell’Aurora, frescoed by four of the leading landscape specialists of the early seventeenth century, namely Paul Bril, Guercino, Domenichino and Giovanni Battista Viola, must have responded to similar reasons. In Rome, interest in landscape painting can also be seen as a reflection of the city’s economy, which thrived partly on the produce of its vast countryside: it has been calculated that Claude Lorrain, for example, produced about half of his three hundred landscapes known to his large Roman clientele.

It has been said that, in the age of the scientific revolution, the rupture that would originate the sense of landscape would become discovery, so much so that the possibility of understanding nature according to a vision that could disregard scientific analysis, wrote Joachim Ritter quoting Von Humboldt, would presuppose that, alongside the sciences of discovery and the “associative activity of reason,” had been succeeded “with equal dignity by the organ of the aforementioned mission, the ’stimulus’ of that ’world-view,’ that is, the ’pleasure’ which the ’view of nature’ guarantees ’independently of the cognition of the operating forces.’” There is probably no need to imagine such a pronounced crack between a way of seeing reality according to the yardstick of science and a vision that is instead related to art, a contrast between scientific and aesthetic feeling: one would not otherwise explain a painting such as Adam Elsheimer’s Escape to Egypt , which sets the Gospel episode in a forest illuminated by the glow of a moon and a starry sky executed as if the artist had scientific knowledge of what he was doing (so much so that it has been speculated that he was familiar with Galileo’s astronomical studies). Indeed, landscape painting, especially in early 17th-century Italy, aimed to recompose, through art, that dichotomy between real and ideal that had characterized the genre’s beginnings: the views that had arisen in sixteenth-century Flanders were not merely products of fantasy, but were glimpses of landscapes animated by picturesque effects, violent contrasts of light and shadow, and unrealistic colors; they were often animated by the intention of accentuating an emotional charge, a dramatic charge. In the Rome of the early 1720s, in the short time that Gregory XV was on the papal throne, the idea of wanting to admire views of real landscapes had directed the artistic choices of the Ludovisientourage , who for the aforementioned Stanza dei Paesi wanted to call painters who were able to mitigate these excesses and restore credible landscapes. In the Ludovisi collections, in 1633, there were attested “two companion countries 7 palms high in about gilded frame by the hand of Domenichini,” namely Domenichino’s Landscape with Hercules and Cacus and Landscape with Hercules and Acheloo : to these “two countries” Bellori probably alluded in his Lives where, about some paintings with the labors of Hercules, he wrote that “every part of the site is chosen and most natural.” But even further north, artists were urged to be inspired by nature: as early as 1604, Karel van Mander, in his Schilder-Boeck, the “Book of Painting,” a modern treatise on art theory, reserving an entire chapter for landscape painting (this was the first time this had happened), advised young artists to “go and look at the beauty out there [...] there we will see many things that we need to compose landscapes.”

The idea that landscape painting was an attempt at recomposition also pervades the pages of Ritter, who, to explain this sense of loss, called into question a poetic work by Friedrich Schiller, Der Spaziergang, “The Walk,” in which the protagonist, a wayfarer, leaving home “fleeing from urban imprisonment and the boredom of miserable talks,” seeks refuge in nature. This is not, however, a simple juxtaposition of city and country: were it so, the mere act of total immersion in nature would suffice to fill the sense of loss that Western civilization is beginning to feel. The city, for Schiller, is the seat of human freedom that works, transforms, and sells the products of nature, and living in the city is a prerequisite for “freedom in science and industriousness” to be expressed: the reification of nature is thus a necessary condition for human freedom to take place, so that human beings can no longer be slaves, but legislators of nature. It follows that the total return to nature no longer becomes possible, so landscape, especially through its aesthetic representation, has “the positive function,” Ritter writes, “of keeping open the bond between man and the quiet surrounding nature, making sure that this bond is visibly expressed and manifested.” Consequently, “landscape, understood as the visible nature of life on earth conforming to the Ptolemaic conception, belongs to the split structure that characterizes modern society.”

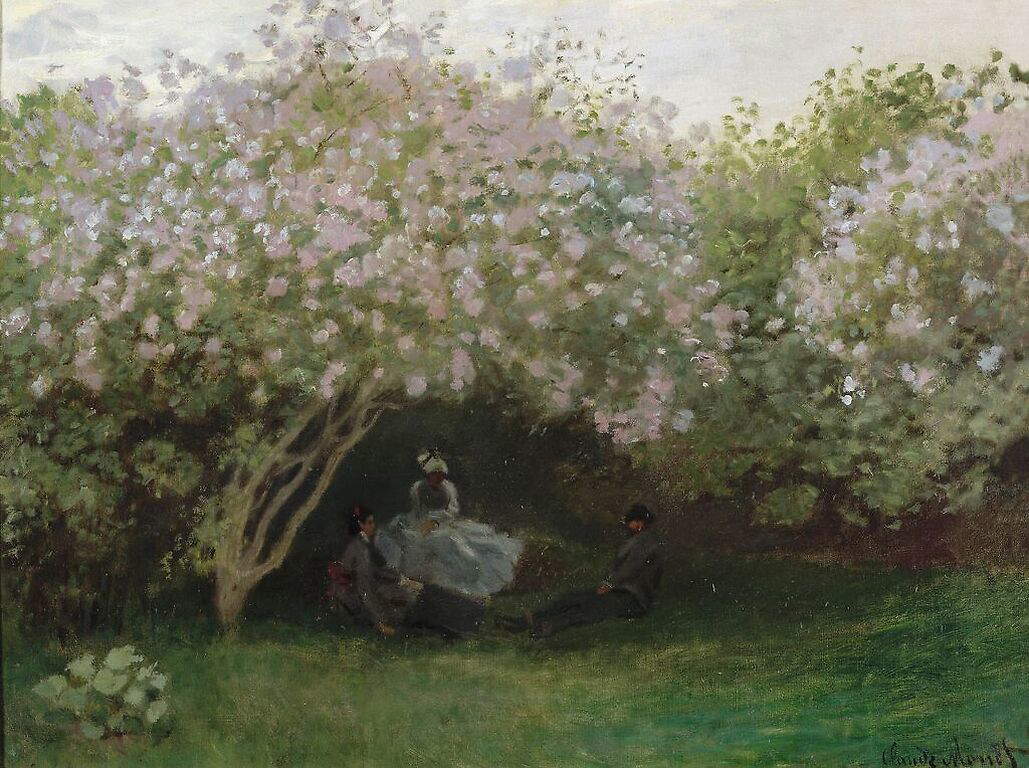

The fact that landscape painting helps to fill a void, to heal a sense of loss, is also inevitably reflected in the relationship between the individual and the work of art. The practice of buying a painting as a souvenir of travel, as is well known, was widespread among the grandtourists who traveled through Italy in the late seventeenth and early nineteenth centuries to learn about its treasures. In 1740, a 23-year-old Horace Walpole, in an April 23 letter to Henry Seymour Conway, wrote: “I have had my fill of medals, lamps, idols, prints, etc., and all those little things to buy that I can get. I would even buy the Colosseum if I could.” And among the purchases there was no shortage of paintings: we know from his correspondence that Walpole bought, for example, several works by Giovanni Paolo Panini, of which, moreover, some trace also remains in the inventories of the family’s collections. Memory is the trace of an event, and can be understood as a mechanism that memory activates to shorten the distance to a loss. A painting can not only help to attenuate the indeterminacy of recollection: it has the potential to elicit a profound experience, as John Berger has explained with supreme effectiveness, taking Monet’s Lilacs as an example, due to the fact that in his opinion the vagueness of an impressionist painting is better able to activate this mechanism (but anyone can carry out the exercise with any painting, since sensations are subjective): “The manifestation of the memory of our sense of sight is evoked so keenly that other memories related to other senses - scent, heat, humidity, the texture of a dress, the length of an afternoon - are in turn extracted from the past [...]. We plunge into a kind of vortex of sensory memories, heading toward an increasingly evanescent moment of pleasure, which is a moment of total recognition.” And even where the landscape is not intended to evoke a memory, the attempt at recomposition does not fail: one thinks of Friedrich and the landscapes of the Romantic painters, who were forced to live in the disagreement between the intimacy of their existence and the immensity of the space that opened beyond the windows from which they saw the world (so much so that the window is a recurring topos in Romantic painting), a disagreement that translated into the unattainable desire for infinity(Sehnsucht, the Germans had called it, after the title of a poem by Joseph von Eichendorff that opened with the motif of the window open to the countryside: “The stars shone with golden light / And I stood alone at the window / And listened to the distant sound / Of the post horn in the still countryside. / My heart burned in my body / And I secretly thought, / Ah, if only I could travel there too / On this magnificent summer night!”

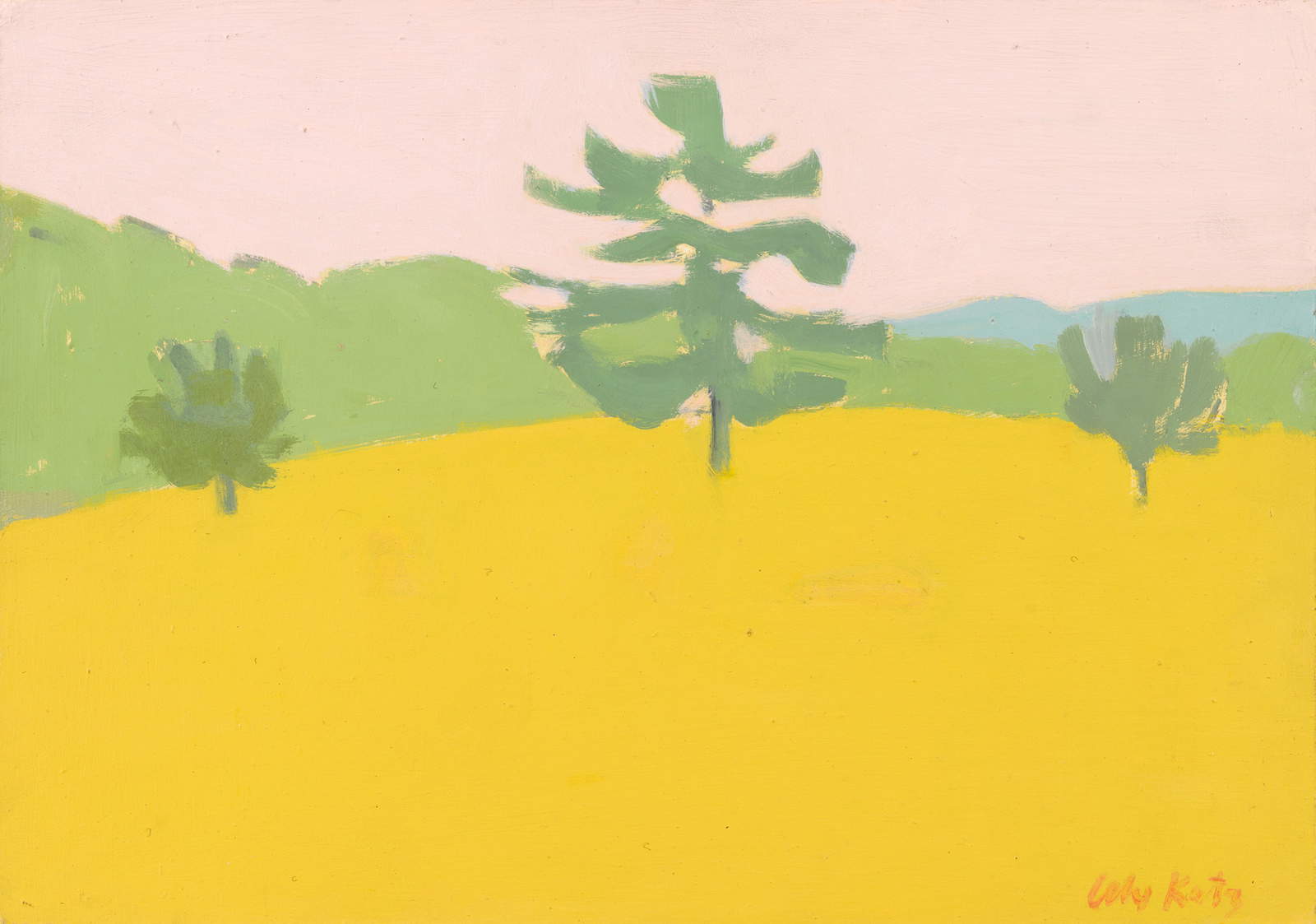

The atmosphere Van Gogh wanted to evoke with his paintings, it was said in the opening, is crucial to understanding the reasons for those works, as well as one of the reasons why we are so attracted to landscape painting, even now: landscapes still enjoy a very wide fortune today, there are not a few great and very great contemporary artists who practice the genre (Hockney, Kiefer, Katz, Alÿs, Stingel and one could go on and on), and every art fair, from the most important to the small provincial kermesse, is filled with landscape paintings. After all, it is not difficult to list the reasons why we all have a landscape painting we like: it is immediate, it is inspirational, it evokes a memory, it stirs a feeling, it depicts a place we love and to which we want to return (those who frequent painting auctions know very well what they are up against if there is a painting for sale depicting a clearly identifiable place: usually battles break out).

By the end of the nineteenth century, the idea would spread that a landscape reflects a state of mind: “any landscape,” wrote Henri-Frédéric Amiel in his Journal intime, “is a state of mind, and those who know how to read both will be amazed to find the similarity in every detail.” Amiel had realized that external phenomena have a reflection on the interiority of the individual and that, conversely, human beings are able to project their feelings onto reality. Van Gogh was not familiar with the Journal intime, published between 1883 and 1884 (or, if he was familiar with it, we do not know, but that would be strange: from his letters we get a deep insight into his readings), but this concept was nonetheless already felt more or less consciously by artists well before Amiel. And above all, Van Gogh had sensed that a landscape can be loaded with its own accents: it can be done, following Simmel, because a landscape is a delimited piece of a totality, even when one wants to consider it as an attempt to sew up a separation, to fill a void. The example of Van Gogh’s letter is useful to make clear how difficult it is to circumscribe the Stimmung of a landscape, as Simmel called it, using an untranslatable term in Italian, which we could render as “intonazione,” although it would not be entirely faithful, because Stimmung is an intonation whose cause escapes us: to what extent does this tonality “have its objective foundation in itself, since it is still a spiritual condition, and can therefore be found only in the reflected feeling of the observer, and not in external, unconscious things?”. The landscape reveals itself to us who observe it as a reflection of a state of mind that we project onto that piece of nature or city that we are observing, but at the same time that piece of landscape seems to act on us, seems to be endowed with its own tonality that we try to grasp. However, we cannot determine whether our representation of the landscape comes first or the feeling that the landscape seems to have. Probably not even Van Gogh would have been able to say whether the projection of his anguish onto the landscape came first or the salubrious effect that the landscape aroused on him. What is certain is that that view had an intonation for him. And this intonation is also one of the reasons why we are attracted to landscape painting.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.