Why are Fernando Botero's figures fat?

One of the contemporary artists who mark the greatest distance between critics and public is surely the Colombian Fernando Botero (MedellÃn, 1932). Unconditionally loved by much of the public and looked down upon by many critics, if not snubbed or even rejected. In a 2011 article in Art in America Magazine, critic Charmaine Picard quoted curator Rosalind Krauss’ 1999 assessment of the artist that Botero “has absolutely nothing to do with contemporary art.” And Picard herself makes us aware that Botero’s figures “are destroyed by detractors as simplistic caricatures of flesh-and-blood figures set in sunny familiar contexts.” For Arthur Danto, his sculptures “are not serious enough to attract critical scrutiny.” Other judgments were picked up by Edward Sullivan in an essay on the Colombian artist: he was thus alternately called a commercial phenomenon, a self-referential author, and an artist disconnected from reality. Of course, there is also a good portion of critics who, on the other hand, appreciate Botero’s work: despite this, the gap between the world of “insiders” and that of the public remains very clear, for whom Botero is considered a sort of icon of contemporary art, recognizable on a par with the greatest artists of all time, from Leonardo da Vinci to Warhol via Caravaggio and Picasso.

|

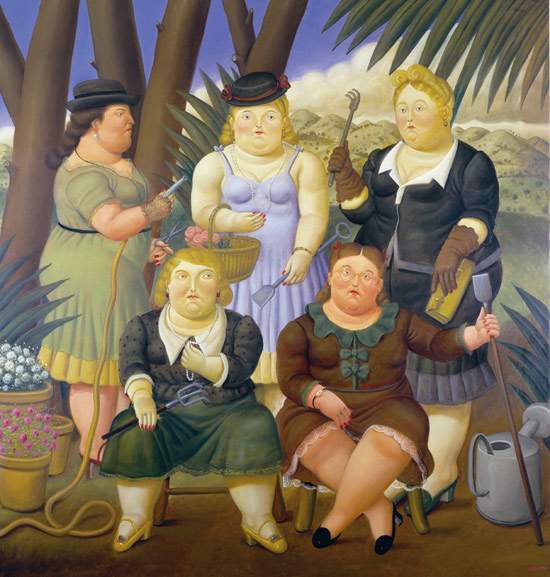

| Fernando Botero, The Garden Club (1997; oil on canvas, 191 x 181 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Fernando Botero, The Card Players (1991; oil on canvas, 152 x 181 cm; Private Collection) |

There is no doubt that his extreme recognizability is due to his peculiar style, which is as true to itself as it is not difficult to read, based on the use of so-called dilated forms that give rise to the"fat figures" that constitute a distinctive feature of Botero’s art to the point of making it almost proverbial (it will have happened to almost anyone to hear the MedellÃn artist’s works referred to in comparisons with friends or acquaintances with a few extra pounds). However, one of the questions one hears most frequently pronounced in front of Fernando Botero’s works (and we at Finestre Sull’Arte know this well since we live near Pietrasanta, a town where the artist spent long periods of work and rest, and where many of his works are preserved) concerns precisely those so recognizable forms: “why does Botero paint fat men?” “Why does Botero sculpt fat women?” These are questions that echo often before his paintings and sculptures. Let us therefore try to provide an answer.

It all began in 1956, when the artist was twenty-four years old, and contrary (and also somewhat unexpectedly) to what one might think, Botero did not apply his"dilation" to a human figure or a living being, but to an object: a mandolin. The artist was painting a study for a still life (later to become known as Still Life with Mandolin) and had, however, depicted the instrument’s resonance hole in much smaller proportions than normal, with the result that the mandolin appeared much stockier and enlarged than a mandolin depicted with the hole in the correct proportions. The artist was both impressed and viscerally attracted to this dilated form beyond the natural, because it evoked a deep sensuality in him. After therefore “dilating” the mandolin, Botero found his style, and began to dilate the forms of other objects, animals, and human beings, giving them all that “fat” look that constitutes somewhat of his trademark.

|

| Fernando Botero, Still Life with Mandolin (1957; oil on canvas, 67 x 121 cm; Private Collection) |

However, in Botero’s eyes, his would not simply be “fat figures.” He also made this clear in a recent interview with Agence France-Presse: “I do not paint fat women. No one will believe it, but it is true. What I paint are volumes. When I paint a still life I always paint volume, if I paint an animal I do it volumetrically, and the same goes for a landscape. I am interested in volume, in the sensuality of the form. If I paint a woman, a man, a dog or a horse, I always have this idea of volume, and I don’t have an obsession with fat women at all.” This is nothing new, however: Botero has always specified that for him it is not “fat” what we see painted or sculpted in his works. In a monograph on the Colombian artist published in 2003, critic Mariana Hanstein had also tried to take stock of the question"why are Botero’s figures fat?“: ”In Botero, it is not only the figures that are ’fat,’ because this is also true for all the objects in the image. In this way Botero constantly emphasizes the fact that in his painting exaggeration is triggered by an aesthetic concern, and it serves a stylistic function. Botero is a figurative painter, but he is not a realist painter. His figures are anchored in reality, but they do not represent it. Everything in his paintings is voluminous: the banana, the bulb, the palm tree, the animals, and, of course, the men and women. Botero [...] uses transformation or deformation as a symbol of the transformation of reality into art. His creativity and aesthetic ideal are based on form and volume. [...] However, deformation without an objective results in figures that are either monstrous or caricatural. In Botero it is neither of these cases. On the contrary, for him deformation always comes from the desire to increase the sensuality of his paintings."

The question that may arise at this point is: why does Botero believe that the dilation of forms is sensual, especially if we think that his ideal of a woman, as he himself stated, corresponds to a slender figure? The artist, as he has had occasion to affirm, associates the forms of his subjects with pleasure, with the exaltation of life, because abundance communicates positivity, vitality, energy, desire: all concepts that have to do with sensuality, understood, however, not so much in an erotic sense as as an expression of pleasure. This is an ancestral conception, rooted in the cultural substratum of primitive societies, including those of Latin America, for whom beauty and abundance were closely related concepts (even today, for many South Americans, a beautiful woman is considered such by virtue of her generous form).

Dilation has thus become the most immediately recognizable sign of Fernando Botero’s style, so powerful that it is applied even to those subjects that everything should inspire less than pleasure (the artist, throughout his career, has also dealt with tragic themes in his works, beginning with the Passion of Christ, to which he dedicated a cycle of paintings executed between 2010 and 2011). For some, his works are unserious, almost childish. For others they are repetitive and boring. For still others they are endowed with deep meaning (a critique of consumer society, an alternative proposal for a canon of beauty, and so on). What is certain is that Fernando Botero is an artist who, undoubtedly, causes discussion at every latitude and is appreciated by a vast and heterogeneous public, which everywhere flocks to his exhibitions: a sort of modern idol of art invested with such a role by popular acclamation. Not bad for an artist celebrated mainly for his “fat figures...” !

|

| Fernando Botero, The Kiss of Judas (2010; oil on canvas, 138 x 159 cm; MedellÃn, Museo de Antioquia) |

Reference bibliography.

- John Sillevis, The Baroque World of Fernando Botero, Yale University Press, 2007

- Mariana Hanstein, Fernando Botero, Taschen, 2004

- Solange Auzias de Turenne (ed.), Botero à Dinard, exhibition catalog (Dinard, Palais des Arts, July 5-September 23, 2002), Cercle d’Art, 2002

- Ana MarÃa Escallón, Asa Zatz, Botero: New Works on Canvas, Rizzoli, 1997

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.