Who were Hitler's favorite artists? The list of the "blessed by God"

In the run-up to the start of World War II, the Reich Ministry of Public Education and Propaganda under the leadership of Joseph Goebbels (Rheydt, 1897 - Berlin, 1945) created a list, the so-called Gottbegnadeten-Liste (“List of God’s Blessings”), of artists and intellectuals considered essential to the Nazi regime. The list included cultural workers and was intended to ensure that key figures could continue their work without being called to military service in the Wehrmacht, the German armed forces, and allowed them to concentrate on cultural and artistic production for Nazi propaganda.“The Reich Minister,” the letter of exemption read, “in your capacity as President of the Reich Chamber of Culture, has exempted you from military service because of your artistic achievements.Since you are not yet in possession of a corresponding notification from the Reich Chamber of Culture, please consider this letter as an official notification and submit it to your appropriate placement office.”

The Nazi regime under the leadership of Adolf Hitler (Braunau am Inn, 1889 - Berlin, 1945) had a clear and equally rigid view regarding art and culture, using them as tools to promote and legitimize its power and ideologies. The Gottbegnadeten-Liste drawn up by Minister Joseph Goebbels’ Ministry of Propaganda in 1939 and updated in 1944 was a practical and obvious manifestation of the control exercised. The regime thus aimed to represent and celebrate values of strength, racial purity, celebrated through the concept of the Übermensch (Übermensch) and disciplined through a model of art that reflected the idealized aesthetics of the Third Reich. As a result, modern, abstract and experimental art, considered "degenerate, " was rejected and banned. Only L’Île des morts(The Island of the Dead) by Arnold Böcklin (Basel, 1827 - San Domenico di Fiesole, 1901) with its enigmatic atmosphere and emotional and hypnotic charge was an exception. Hitler, who owned the third version of the painting, considered it his most beautiful painting. But why specifically L’Île des morts? Because it reflected the regime’s attraction to elements that despite not conforming to Nazi propaganda evoked fascination, fanaticism, power and symbolism. And that attracted the Nazis.

The Führer himself, who in his youth desired to become a painter and saw his aspirations fade as a result of failing the entrance examination at theVienna Academy of Fine Arts, used his position to manipulate art to suit his ideological views. He favored works that evoked a return to traditional values, reflecting an idealized view of Germany and humanity, appreciating idyllic landscapes linked to a romantic idea of the past. In fact, he was not limited to appreciating only landscape art and Romanticism.Artists such as Adolf Ziegler (Bremen, 1892 - Varnhalt, 1959), a painter originally from Bremen, and Leni Riefenstahl (Berlin, 1902 - Pöcking, 2003), director of the famous 1938 film Olympia, were among his favorites because of their celebration of physical beauty and the perfection of the Aryan body recalling the idealization of Greek perfection. Their works embodied the dream of racial purity and imperial grandeur, extolled athletic superiority and thus contributed to the promotion of the regime’s identity.

In 1944, 1,041 individuals received an official letter of exemption from the war from the Reich Ministry of Propaganda. Of these 1,041 named figures, 378 personalities from the fields of fine arts, literature, music, theater and architecture were part of the Gottbegnadeten-Liste, now preserved in theFederal Archives in Berlin-Lichterfelde. The list was divided into two categories: Special Lists of Irreplaceable Artists and All Others. The Gottbegnadeten-Liste thus had a duty to shape German culture according to its own uncompromising ideals. It undoubtedly favored artists who helped uphold and spread the right worldview by repressing art that did not conform to such ideologies. Why then, according to National Socialist thought, were artists considered “blessed by God”? The expression served to bestow a form of divine legitimacy on the selected artists, elevating them as representatives of Nazi cultural aesthetics and that in turn was linked to the thought of the purity of the Aryan race. Indeed, Nazi officials used this concept to support the idea that Germans belonged to a superior race. The artists that the Reich Ministry had included in the lists were therefore considered chosen because of the innate talent inherent in their souls. Their qualities, interpreted as a God-given grace, distinguished them from the modern artistic avant-gardes that Hitler despised and judged to be expressions of a decadent and corrupt culture. The use of the term “blessed by God” was thus intended to ennoble artists who embodied the supreme values of National Socialism, assigning them the task of creating eternal, immortal works of art that would exalt the greatness of the German nation. Indeed, in his speech at the cultural conference of the National Socialist Party Congress in Nuremberg in 1933, Hitler declared that “Only a few God-given people [...] at any time have renounced the mission of creating something truly new and immortal,” since “the embodiment of the ’highest values of a people’ would be directed against the characteristics of modernity.” Four years later, during the opening speech of the first Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung, the Great German Art Exhibition, in the Haus der Deutschen Kunst, the House of Art in Munich, Hitler described Cubism, Dadaism, Futurism, Impressionism as the “artificial stuttering of people to whom God denies the grace of true artistic talent.”

The selection of artists included in the list also followed criteria influenced by a combination of ideologies, a National Socialist aesthetic, and personal relationships with the regime’s top leadership. First, the artists had to align themselves with the aesthetics and ideology of Nazism. Works had to reflect and embody the values of the Aryan race, ethnic purity and national greatness. Any art form that was experimental, abstract or modernist was excluded from the artistic expressions approved by the regime. Hitler and the regime leaders sought works that glorified the nation, military heroism and idealized physical beauty. Second, there was a predisposition for a figurative, monumental, neoclassical style inspired by the great art of the past, particularly Greek and Roman art. Sculptors and painters who created heroic works celebrating the physical and moral strength of the German people were definitely favored. As a final criterion, artists who had already achieved notoriety or had been exhibited in art exhibitions such as the Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung, the Great German Art Exhibition in Munich, were more likely to be included. An example? Arno Breker, Adolf Wamper, Adolf Ziegler exhibited their works inside the Haus der Kunst as early as 1937. Inside, the Hall of Honor was dedicated to the exaltation ofauthentic German art characterized by a neoclassical taste and closely linked to the propaganda of Nazi theories. Prominent names in the Special Lists of Irreplaceable Artists section included architect Paul Schultze-Naumburg, Wilhelm Kreis, and writer Gerhart Hauptmann. Present were composer Richard Strauss, sculptors Arno Breker and Josef Thorak, Leni Riefenstahl and painter Otto von Kursell, along with Willy Kriegel, a specialist in romantic landscapes and plant miniatures. In addition, Richard Scheibe who studied painting in Dresden and Munich, and Adolf Ziegler who was present in the campaign againstdegenerate art, were included in it. Ziegler in particular had played a significant role in expelling the most innovative artists of the time and the works of previous generations.

“We still have a sad duty to perform, namely, to make even the German people aware that until not so long ago they exerted a decisive influence on the creation of art forces who did not see in art a natural and clear expression of life, but consciously renounced what was healthy and cultivated all that was sick and degenerate and praised it as the highest revelation. You see all around us these children of madness, insolence, incompetence and degeneracy,” were the words spoken by Adolf Ziegler at the 1937 exhibition, which he personally curated, Entartete Kunst(Degenerate Art), which opened in Munich: these words, in particular, were spoken during his speech against Expressionism and its exponents.

In 1933 Ziegler obtained the chair of painting technique at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts, becoming a full professor the following year. At the same time he joined the Presidential Council and was appointed vice president of the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts. Two years later, in 1936, Goebbels gave him the presidency of the same institution. Hitler particularly appreciated the eroticism in Ziegler’s painting, especially the sensual depiction of his female bodies. It is not surprising, then, that Ziegler, ironically nicknamed “The Master of German Pubic Hair” by his detractors, was well aware of which nudes might find favor with the Führer. Among his most emblematic works is the 1937 triptych Die vierElemente (The Four Elements), purchased personally by Hitler and found at the end of the war in Munich. Other significant works include the mythological scene Das Urteil von Paris (The Judgment of Paris) of 1939, Weiblicher Akt(Female Nude) of 1940, and Terpsichore of 1937, the latter mentioned in a Time magazine review in 1939 that claimed “Almost anywhere else in the world Terpsichore would be considered the kind of image you put on a beer advertising calendar. Not so in the new Germany.”

Hitler’s favorite artists were numerous, and among them was the name Werner Peiner (Düsseldorf, 1897 - Leichlingen, 1984). Initially influenced by realism and the New Objectivity current , Peiner became one of the best-known official painters of the Third Reich, gaining popularity due to his full adherence to the principles of Nazi ideology . In particular, he found inspiration in the teachings of Richard Walther Darré, the Nazi Minister of Agriculture, through his concept of Blut und Boden(Blood and Soil), which extolled the bond between the German people and the land and promoted the purity of the German race and the importance of rural life. In 1933, Peiner was appointed professor of monumental painting at the Düsseldorf Academy of Art, a position that underscored his growing prominence within the Nazi cultural apparatus. It was during this period that he produced one of his most important works, Deutsche Erde(German Land), a painting that precisely embodied the values of the regime and Darré’s thinking. The work presents a landscape with orderly and fertile fields, a symbol of the agricultural prosperity and strength of the German nation. The painting was later given to Josef Schramm, administrator of the Schleiden district, and later delivered personally to Adolf Hitler by Franz Binz, local party leader.

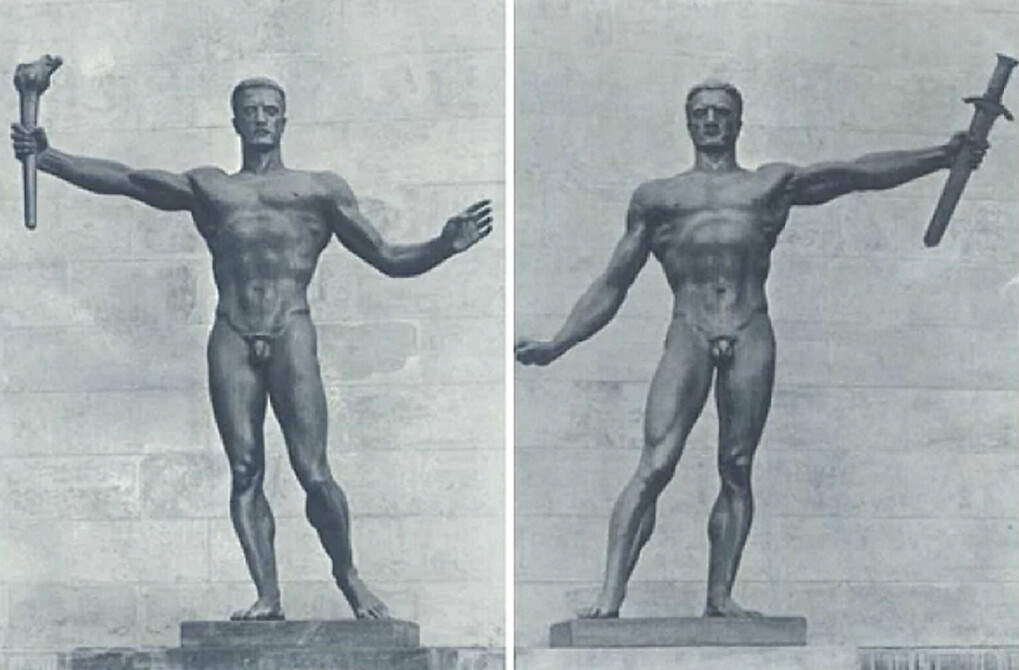

Arno Breker (Elberfeld, 1900 - Düsseldorf, 1991) was also on the Gottbegnadeten-Liste and was the main sculptor in charge of creating propaganda works during the National Socialist years. The son of a stonemason, Breker began his studies in architecture, sculpture and anatomy and at the age of 20 entered the Düsseldorf Academy of Fine Arts. In 1937 he joined the National Socialist Party and became an official State Sculptor. The celebration of power, discipline, and racial purity found expression in his heroic and athletic figures that reflected the ideal of the new Nazi man. The bust of Adolf Hitler, made in 1938, is an example of this as it embodied the commemoration of the Führer figure as a political leader and ideal guide. As an official state sculptor, he had access to privileged resources, including a huge atelier and a large number of assistants (more than forty), which enabled him to produce his monumental works. Indeed, the sculptures Die Partei(The Party) and Die Wehrmacht(The Army) placed at the entrance to the Reich Chancellery are emblematic symbols of Nazi power and the regime’s absolute control. Works inspired by the classical tradition also served to legitimize National Socialist authority with references to the grandeur and order ofancient Greece and Rome, civilizations that Hitler admired for their strength, perfection, and discipline. Commissions of sculptural works for the 1936 Berlin Olympics, such as Zehnkämpfer(Decathlete) and Die Siegerin(The Victorious One) also emphasized the centrality of the Aryan body and athleticism as a representation of superiority and perfection.

The German sculptor Adolf Wamper (Würselen, 1900 - Essen, 1977) studied in Aachen and Düsseldorf, establishing himself as a prominent figure through his classical style and ability to express the values of National Socialist aesthetics. In Berlin he made reliefs for the entrance to the Reichssportfeld outdoor stage at the Berlin Olympic Stadium, which had been built for the 1936 Olympic Games. Wamper received numerous commissions from the government, which appreciated his neoclassical style inspired by Greek and Roman art and characterized by athletic bodies and balanced forms. One example is the sculpture Der Bogenschütze(The Archer), which embodies exactly like Breker’s works the values of virility, discipline, and physical perfection dear to the Nazi regime. Another significant work is Genius des Sieges (The Genius of Victory), exhibited at the Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung, the Great German Art Exhibition, which was held from 1937 to 1944 at the Haus der Deutschen Kunst in Munich and was the showcase of art approved by Nazi Germany. In any case, Wamper’s works suffered significant damage during World War II. In Berlin many of his sculptures disappeared from the urban landscape due to bombing, and his studio was almost completely destroyed in a 1943 air raid. After the war the artist distanced himself from the art associated with the regime and became known for the Schwarze Madonna(the Black Madonna), a sculpture modeled from clay at the U.S. prison camp in Remagen, where he spent the last two months of the war.

Although the Nazi regime had collapsed in 1945, many of the artists included within the Gottbegnadeten-Liste and who had followed National Socialist propaganda continued to work as visual artists. In any case, inclusion on the list did not prevent them from continuing to produce artwork and receive commissions after the war. Adolf Wamper, Willy Meller, and Hermann Scheuernstuhl are examples. The fact that many artists were able to continue to work and receive public recognition in the postwar period represented the complexity of the Entnazifizierung (Denazification) process undertaken in 1945 by the four world powers, the United States, the Soviet Union, England and France, which involved the liberation of German and Austrian society from all forms of Nazi influence, and the will in separating art from the ideology of the period.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.