Where did a Renaissance lord sleep? The alcove of Duke Federico da Montefeltro

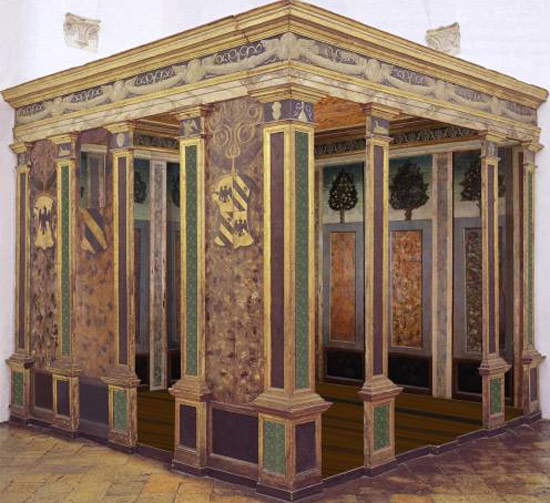

Walking through the rooms of the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, housed in the famous Ducal Palace in Urbino, it is impossible to avoid pausing in front of one of the most valuable pieces in the collection: theDuke’s alcove, which gives its name to Room III of the itinerary, where perhaps, at one time, the lord’s bedroom itself was located. In our case, the term “alcove” does not identify, as is usually the case, the bedroom, but rather a very rare piece of furniture: a large wooden cube (measuring three meters and forty centimeters in height, width and depth), which had the function of housing, precisely, the duke’s bed. Curiously enough, the common meaning, that of “alcove” as “bedroom,” is farther from the original etymon than that of the duke’s alcove, because literally, in Arabic, the expression al-qubba means “bed curtain,” and the term originally designated that part of the room, usually separated precisely by a curtain, intended to house the bed.

We do not know with certainty when the work was made, but it is highly probable that the occasion was the wedding between the lord of Urbino, the future Duke Federico di Montefeltro (Gubbio, 1422 - Ferrara, 1482), at that time awarded the title of count, and Battista Sforza (Pesaro, 1446 - Gubbio, 1472), celebrated in 1460: the work would date from about the same year. However, we have several certainties. The first, one of the most important: the duke’s alcove is one of the very few pieces of the original furnishings of the Ducal Palace that have survived to the present day. The second: the initials “FF” placed on the capitals of the two pilasters flanking the entrance to the alcove (to be read “Federicus Feltrius,” or “Federico da Montefeltro”) leave no doubt as to the work’s recipient. The third: the work is often mentioned in documents. We have an account by Michel de Montaigne, who saw it in 1581 (and we will return to this document later), and a citation in a 1631 inventory that describes it as a fir bossola with cornice, columns, rosettes et altri intagli in pezzi n. cinquanta in circa, qual’era nella camera del Bisquadro ducale, dorata et colorita (the Sala delle Udienze in the palace is sometimes referred to as the “camera del Bisquadro” because of its shape). This is the last document before the discovery of the alcove, which was found, disassembled, in the salt storerooms of the Ducal Palace (but several fragments had been taken to other rooms): it was 1894.

|

| Fra’ Carnevale, Duke’s Alcove (1459-1460; painted and gilded wood, 340 x 340 x 340 cm; Urbino, Galleria Nazionale delle Marche) |

After the “rediscovery,” the various parts were deposited in the Salone del Trono so that they could be better studied. It had to wait until 1912, however, for the alcove to be reassembled: art historian Luigi Nardini discovered what the function of this valuable piece of furniture was and decided to place it in the duchess’s apartment. Nine years later, another scholar, Luigi Serra, decided to move the alcove to theapartment of Jole, the oldest nucleus of the palace, so called because the fireplace in the first room is adorned with a sculpture depicting the mythical Jole, daughter of the king of Thessaly and lover of Hercules. The last “relocation” was in 1948, when Pasquale Rotondi moved the alcove from the first to the third room of the Jole apartment, where it can still be admired today. Documents attest that the room was actually inhabited by Federico da Montefeltro, and the choice of placing the alcove in a corner of the room was dictated by the fact that the work was perhaps placed right in a corner (as was typical for such pieces of furniture). We were saying about Montaigne: the French philosopher left us a description of the alcove in which its placement is also mentioned. Here is what he wrote: en deus de leurs chambres, il s’y voit d’autres chambres carrées en un coin, fermées de toutes pars, sauf quelque vitre qui reçoit le jour de la chambre; au dedans de ces retranchemens est le lit du maistre (“within two of their chambers, one sees other square chambers, placed in a corner, which have all their walls blind, except for some glass which receives the daylight from the room; and within these constructions is the bed of the lord.”). Montaigne’s passage is interesting not only because it gives us clues as to the location (although it is not certain that in Federico da Montefeltro’s time it was located in a corner: and in fact not all scholars are convinced of this), but also because it informs us that there were at least two similar works: the second one (or at least the one that was probably the “sister” of the one we still see today) is mentioned in a 1609 inventory, and given the size of the objects contained in it, it is hard to imagine that it was the alcove now located in Jole’s apartment. Unfortunately, however, only one has come down to us.

Let us try to get a better look at it. Certainly, it has not come to us intact: we know that some of the boards were reused for other purposes, and certainly in the work as we see it today there is no trace, for example, of the “rosettes” mentioned in the 1631 inventory. The three wooden walls house elegant pilasters supporting an entablature composed of a faux-marble architrave, a frieze with putti holding festoons, and a gilded cornice. In the capitals of the pilasters we find several feltresque symbols: the initials “FF” mentioned above, theermine (a symbol of purity particularly dear to the family), the eagle (which also appears in the family coat of arms), the bursting grenade (a symbol of the lord’s military valor), the broomstick (a symbol of moral integrity, probably associated with Battista Sforza), the flames (a probable allegory of love), and the dynastic coat of arms. The walls are also adorned with decorations simulating polychrome marbles beyond which we see trees laden with flowers and fruits silhouetted. Above the marbles, we also observe some birds in various poses. The decoration with marbles and trees is also repeated in the back wall inside. The entrance wall, on the other hand, houses the usual faux marbles, however, with the Montefeltro coats of arms hanging from two garlands. It should be pointed out that according to one scholar, Dante Bernini (later followed by others, such as Paolo Dal Poggetto), the walls with marbles, trees and birds (i.e., those with the “viridario,” the enclosed garden, to use the term used by Bernini himself), were facing inward, so that the lord of Urbino could fall asleep pretending to be in a lush garden of a taste still linked to the courtly tradition: a hypothesis that would seem to be confirmed by the candle burns used to illuminate the interior of the alcove, which are found on the panels now facing outward. Finally, the ceiling is decorated with a pattern in which pomegranates and thistles are intertwined, simulating a fine drapery.

|

| The entrance wall of the Duke’s alcove. |

|

| Detail of the entrance: on the pilasters, note on the left the ermine enterprise and on the right the initials FF |

|

| Detail of the entrance: note the Feltresco coat of arms hanging from the wreath and, on the pilasters, on the left the initials FF and on the right the enterprise of the grenade |

|

| Detail of the interior |

|

| Detail of the ceiling |

|

| Detail of the wall with the trees and birds and, in the capitals of the pilasters, the Montefeltro coats of arms |

|

| Detail of the wall with the trees and birds and, in the capitals of the pilasters, the eagle on the left and the Montefeltro coat of arms on the right |

Since the date of its discovery, Federico da Montefeltro’s alcove has undergone a number of restorations, the last of which took place between 2004 and 2007, aimed primarily at improving the legibility of the work. The work began with the analysis of the wood species used to fabricate the alcove: samples were taken that allowed us to understand how the structure was made of spruce, while the carved parts are made of linden wood. The investigation of the wood species was to provide crucial information for the choice of wood with which to make the inserts to supplement some missing fragments, for example, certain pieces of the pilasters. The next investigation wasstratigraphic analysis, which makes it possible to detect information, often impossible to grasp with the naked eye, about the compounds used, the pigments, the preparation of the support, and so on. Other information about the materials then came from radiographic and ultraviolet fluorescence investigations, which were useful for confirming the results of the stratigraphic analysis and for detecting details about the structure, the way the work was constructed, and the state of the paint film: the ultraviolet fluorescence investigation, in particular, confirmed the presence of various and extensive repainting. These were removed in the first “operational” stages of the intervention: more in detail, the removal of the repainting allowed the original colors of the faux marbles to be recovered. Then proceeded with the removal, through special solvents, of the materials affixed in later periods, whose presence was detected thanks to stratigraphic analyses. Finally, the gaps were supplemented and old fillings, no longer needed thanks to the cleaning of the pictorial film, were removed. The missing pieces of the latter were also integrated, through the use of watercolor paints. The last operation was the application of a protective varnish to better preserve the work. During the work, an appreciable reconstructive hypothesis was also formulated thanks to a virtual reconstruction carried out by the Central Institute for Restoration in Rome, which was also in charge of the preliminary analyses (directed by Francesca Romana Mainieri). Instead, the interventions were carried out by the Bacchiocca company of Urbino under the direction of Maria Giannatiempo López.

|

| Virtual reconstruction of what the alcove must have looked like originally |

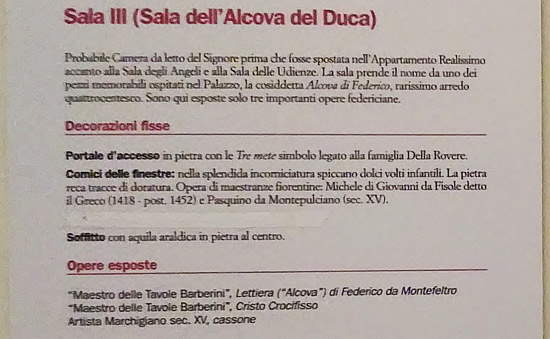

We have not yet said which artist should be credited with creating such a fine work. For a long time the name of the maker of the alcove remained an important knot to untie. The first to try was, in 1912, Egidio Calzini, who formulated the name of Paolo Uccello, a hypothesis also accepted by Luigi Nardini. Luigi Serra, on the contrary, thought of assigning the work to an artist akin to the manner of Piero della Francesca and Melozzo da Forlì. Rotondi, on the other hand, thought that the alcove was the work of a sculptor, and proposed, in 1950, the name of Domenico Rosselli. The decisive contribution, that is, the one that proposed the hypothesis currently considered the most reliable, was that of Federico Zeri dated 1961. The celebrated art historian believed that the alcove was made by the so-called Master of the Barberini Tables, an artist whose profile he was reconstructing at the time, going so far as to identify him with Giovanni Angelo da Camerino. Later, however, it came to be thought that the Master of the Barberini Tables was actually Bartolomeo Corradini, better known as Fra’ Carnevale (Urbino, 1416 - 1484), one of the most important Urbino painters of the time: an identification later confirmed by the 2004 exhibition on Fra’ Carnevale himself. A curiosity: in the Gallery, the illustrative panels listing the works in Room III of the Jole apartment still refer the work to the Master of the Barberini Tables: a sign that the last update was probably more than a decade ago.

|

| The panel...to be updated |

Zeri had spotted the very close resemblance between the frieze with cherub heads in the entablature of the alcove and the one that appears in one of the two Barberini Tables, the Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. In addition to this, Zeri emphasized the closeness in the making of the polychrome marbles and the recurrence, in other works that could be associated with the artist, of certain characters, such as the putti’s hair. On the occasion of the aforementioned 2004 exhibition, Matteo Ceriana identified a possible inspirational model for the architecture of the alcove, namely the first order of Palazzo Rucellai in Florence. We know that Fra’ Carnevale was in Florence, where he studied with Filippo Lippi (Zeri also pointed out the affinities between the decorations of the alcove and Lippesque painting) and where he was fascinated by the perspective solutions of Filippo Brunelleschi and Leon Battista Alberti: the latter was, moreover, the author of the design of Palazzo Rucellai. Fra’ Carnevale, working on Alberti’s ideas, eliminated the ashlar cladding (obviously unnecessary, Ceriana pointed out, the alcove being a piece of furniture) replacing it with the “luxurious mixed marbles learned at the school of Lippi” and designing the sky “of brocaded fabric on the inside, entirely worthy of the copes of Domenico Veneziano and the frontals of Giovanni di Francesco” and adding the “garland held up by putti of the purest Florentine extraction, Michelangelo’s.” While there is now no longer any doubt that the structure, frieze and marbles can be attributed to the hand of Friar Carnevale, some doubts remain about the trees. Ceriana himself warned that "it was left to some heir of the workshop of Antonio Alberti [a painter active at the Feltresque court at the time, ed.] the execution of the saplings which, in fact, still have the artisan grace of the flowering lawns composed in collage in the late Gothic workshop."

|

| The comparison between the frieze of the alcove and that of Friar Carnevale’s Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple preserved in Boston |

|

| The comparison between the architecture of the alcove and that of Palazzo Rucellai in Florence |

As extensively described above, today we see the alcove deprived of some of its parts (the door, for example) and reconstructed with the interior walls facing outward so that we can fully appreciate the decorations, since there is no access to the interior. In spite of this, the importance of a work that is not only (and we have not yet mentioned this) the only work of Friar Carnevale remaining in the place for which it was made, but is also a rare remaining piece of the original furnishings, a testimony to the usages of a 15th-century court, further evidence of the refined tastes of a gentleman who contributed decisively to the establishment and development of the Renaissance, remains unquestionable.

Reference bibliography

- Alessandro De Marchi, Maria Rosaria Valazzi (eds.), The Renaissance in Urbino: Fra’ Carnevale and the Artists of the Palace, exhibition catalog (Urbino, Palazzo Ducale, July 20-November 14, 2005), Skira, 2005

- Matteo Ceriana (ed.), Fra Carnevale: un artista rinascimentale da Filippo Lippi a Piero della Francesca, exhibition catalog (Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera, October 13, 2004 - January 9, 2005; New York, Metropolitan Museum, February 1 - May 1, 2005), Olivares, 2004

- Paolo Dal Poggetto, The National Gallery of the Marches and the Other Collections in the Palace, Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato, 2003

- Federico Zeri, Two Paintings, Philology and a Name. The Master of the Barberini Tables, Tea, 1995 (first edition 1961)

- Maddalena Trionfi Honorati, Arredi lignei nelle Marche, Edizioni Bolis, 1993

- Paolo Dal Poggetto, Maria Grazia Ciardi Duprè (eds.), Urbino and the Marche before and after Raphael, exhibition catalog (Urbino, Palazzo Ducale and church of San Domenico, July 30-October 30, 1983), Salani, 1983

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.