When you discover great photographers by rummaging through old suitcases

Photography has a bizarre relationship with suitcases. Ever since the news of the discovery of Robert Capa’s famous Mexican suitcase had a worldwide echo, I began to notice a repeated coincidence of fates between some hidden talents and their travel bags. Fortuitous finds in the world of photography are indeed many: from Vivian Maier ’s legacy discovered in an abandoned box, to Ernest Joseph Bellocq ’s plates found and developed by Lee Friedlander, to Paolo Di Paolo’s forgotten archive. But my attention over time has focused in a somewhat fetishistic way only on the events that had to do with suitcases, because they are the protagonists of a number of rediscoveries in the objectively astonishing.

The most famous is, indeed, the Mexican suitcase of Robert Capa, David Seymour and Gerda Taro, which before its discovery, and for a long time afterwards, was still an unknown. The suitcase and its owners have had a film life, so much so that it was a film( Trisha Ziff’sLa maleta mexicana, 2011) that reconstructed its story, which begins in the 1930s in a Paris at the height of its cultural ferment where Capa, Seymour and Taro arrived after fleeing their respective countries of origin-Hungary, Poland, Germany. They discovered photography and made a profession out of it, eventually achieving some success. The most famous of the three is Robert Capa, who began as a fictional character invented by the couple Endre ErnÅ‘ Friedmann and Gerta Pohorylle-who would later take on the name Gerda Taro-to better sell their photos, and who would later become Friedmann’s stage name for good. By the time a tremendous civil war broke out in Spain in 1936, the three had developed the idea that photography was also a tool for political and social engagement: there was an urgent need to document, but also to take a stand by recounting the pain and devastation of war, even to the point of risking their lives to shoot “close enough” to the battlefields (“if your photos are not good enough, you are not close enough,” said Robert Capa). Their images forever changed the perception of war, and are rightfully considered the first contemporary war reportage. But just approaching the battlefields, Gerda dies at only 26 years old. With her Capa loses the love of his life and the woman with whom he had worked and lived in complete symbiosis in his last years. With this grief, which will change him forever, he returns to Paris.

Two years later, as German troops advance toward the city, he finds himself in a hurry to arrange his escape to New York. Before he leaves, however, there is one vital task that requires his attention: the securing of all photographic material relating to the Spanish Civil War. It consists of no less than 126 rolls of film and 4,500 negatives, belonging not only to him but also to Gerda Taro and David Seymour. He entrusts it to Imre “Csiki” Weiss, his devoted assistant, and sets off. His freedom is, however, short-lived: he is imprisoned by the Americans, accused of being a communist.

So, the entire archive is on Csiki’s shoulders. “Physically” on his shoulders, because he has painstakingly arranged it in a backpack ready to be transported by bicycle to Bordeaux. The goal is to embark the negatives on a ship bound for Mexico, but the young man is aware of the risks he is taking because of his Jewish origins, which is why he entrusts the backpack to a Chilean he meets along the way, asking him to deliver the rolls of film to his country’s consulate to ensure its safety. Next, someone places the negatives in three cardboard boxes, which are then carefully placed inside a suitcase. There it is, the first suitcase in this quest of mine.

From this point on, there are no more witnesses to tell the rest of the story. The traces of the suitcase are lost and it remains only a legend, abetted by the fact that legendary become its owners: Capa and Seymour in 1947 founded, together with Henri Cartier-Bresson, the Magnum photo agency (still the most famous in the world today), and both died a few years later on the battlefield: Robert in Vietnam in 1954, David in 1956, riddled with machine-gun fire while documenting the Suez Crisis.

There are no new traces of the suitcase until 1995, when it is found among the personal effects of General Francisco Aguilar Gonzalez, Mexican ambassador to France during the Vichy government, thanks to one of his acquired nephews, Benjamin Tarver. Initially, Tarver did not want to turn the rolls over to Cornell Capa, Robert’s brother, who had contacted him upon learning of the find. It was only in early 2007, through the intercession of Trisha Ziff, who will make her splendid documentary on this story, that Tarver was persuaded to send it to New York, where it is now stored at the International Center of Photography. The story does not end there, however: it will take a few more years to study the contents of the suitcase, rediscover Gerda Taro and identify her photos among those that were marked with the Robert Capa “mark.” On her story, Helena Janeczek wrote The Girl with a Leica published by Guanda with which she won the Strega Prize in 2018.

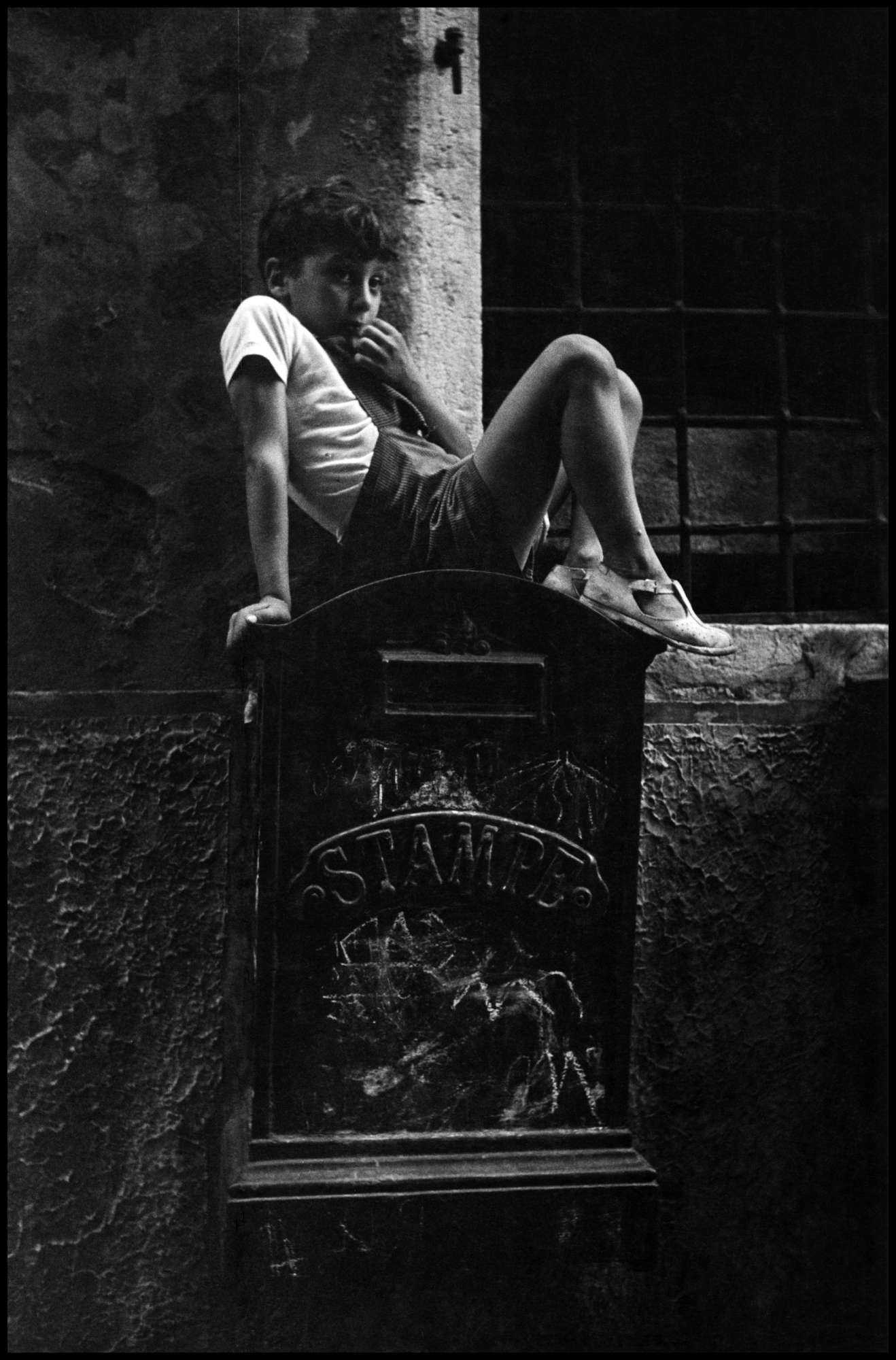

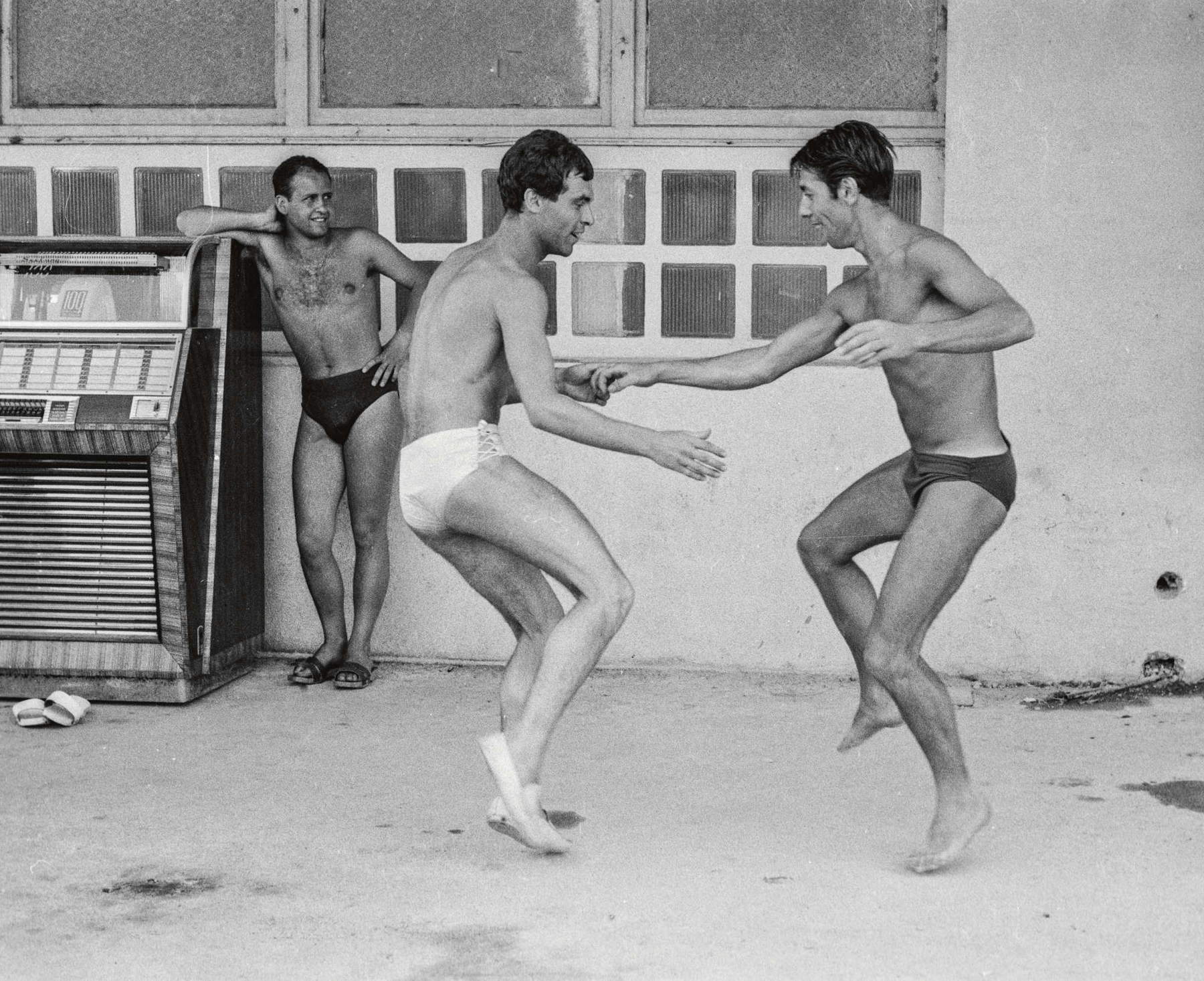

David Seymour

David Seymour

Still a suitcase, or perhaps in this case a precious trunk, collects the albums of Princess Anna Maria Borghese for decades. Born Anna Maria De Ferrari in 1876 in Genoa, she inherited one of Italy’s most conspicuous estates (which included the Isola del Garda estate), which she brought as a dowry when she married Prince Scipione Borghese. He was a radical deputy in the Italian Parliament, a diplomat, a tireless and curious traveler, explorer and mountaineer; she a wife, as was the social custom of the time, discreet and reserved. In European high-society circles he discovered photography, thanks in part to the availability of the first portable cameras put on the market in the late 19th century that made the new medium accessible even to non-professionals.

Although historians classify her works as “amateur,” it clearly appears that they are not the whim of an aristocrat in search of a hobby, but convey a desire to record the reality around her with the clear intent of keeping track of her point of view. Photographer, therefore I am, a modern-day Descartes would say.

Her story has emerged thanks to a valuable book, Tale of an Era. Photographs from the Albums of Princess Anna Maria Borghese published by Peliti Associati, the catalog of the exhibition of the same name held in Rome in 2011 curated by Maria Francesca Bonetti and Mario Peliti. The images truly tell of an era of ferment, of progress, but also of the disenchantment with which the 1920s are steeped. From her privileged vantage point, the Borghese princess records the daily life of the time, her family and friends-which counted figures such as Margaret of Savoy Queen of Italy-and the places she visited alongside her husband. With him she travels to Asia from the Persian Gulf to the Pacific, to Syria, Mesopotamia and Persia, and then also to China, taking her camera with her. When he then embarks on the Peking to Paris raid in 1907, which he wins, she follows him traveling by train along the Trans-Siberian Railway, documenting with curious intelligence places that the eyes of contemporaries could rarely see.

Clear from her photos is her ability to relate with ease to a new language, certainly matured from observing those pictorial images that at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries were the visual reference of early photographers, but it is also a sensitive and original gaze: the cut of the framing, which leaves out tinsel and distractions, the balance of light and shadow, of perspective and vanishing points. There is never a random photo; every choice is refined.

The most striking photos are those of the great dramatic events that wounded Italy in the early twentieth century: from the Avezzano earthquake in 1915 to World War I, which saw her engaged in supporting the nursing services. These are courageous photos, uncensored by the reflections that in the years to come would be made on the representation of suffering, holding a balance between the determination to bear witness to a painfully obscene reality, and the unawareness of the power that certain images carry.

But why do so many photos end up in trunks or suitcases? Come to think of it, before the birth of the famous Swedish furniture line and its “tidy house” department, full of boxes of all sizes and materials, suitcases were a very practical solution for organizing space: large, roomy, and equipped with convenient handles that made them easy to carry. It is also true that suitcases carry with them a strong symbol of hope, the sense of entrusting a treasure trove of images - concrete records of private and universal history - to a future that may have unpredictable directions, far from the photographer’s own life. After all, is this not the very meaning of photography: to stop an instant in order to transmit it to unknown eyes?

This might have been the dream of Giulia Niccolai, writer, poet, essayist, when she closed her photos - not even to mention - in three suitcases to “start another of her many, generous, happy, unpredictable lives,” as told in the book Un intenso sentimento di stupore edited by Silvia Mazzucchelli, with afterword by Marco Belpoliti, just published by Einaudi. It is not just a photographic book, but a magical encounter of images and words that Giulia Niccolai entrusted to Silvia Mazzucchielli, with whom in 2019, only two years before her death, she decided to recover her photographic archive after more than forty years of neglect.

And perhaps in his case the choice of suitcases as the custodians of his work is also consciously symbolic, since travel was a central aspect of his photographic activity: first to Italy, when from 1958 she worked on commissions for a series of volumes entitled Borghi e città d’Italia (Villages and towns of Italy), then to America, her mother’s homeland, where she went as a young amateur photographer in 1954 and then returned in 1960 as a photojournalist to chronicle John Fitzgerald Kennedy’s election campaign. These are powerful historical documents, which multiply in meaning when they meet Giulia’s words as she revisits them years later, more disillusioned, but also more mature, having left behind many events, including the tragic decision to end photography for good when one of her reportages was completely manipulated by the newspaper that commissioned it. “Photography works like stumbling stones: It forces you to make encounters with what has been, even if you, the witness, have removed or tried to do so,” says Silvia Mazzucchielli, who reconstructs the history of an ’era of extremely vivid for Italian photography and culture, but she also knows how to entrust readers with Giulia Niccolai’s personal story with the gentleness of a friend and a deep sense of responsibility for the important legacy of a historical testimony that she found herself handling.

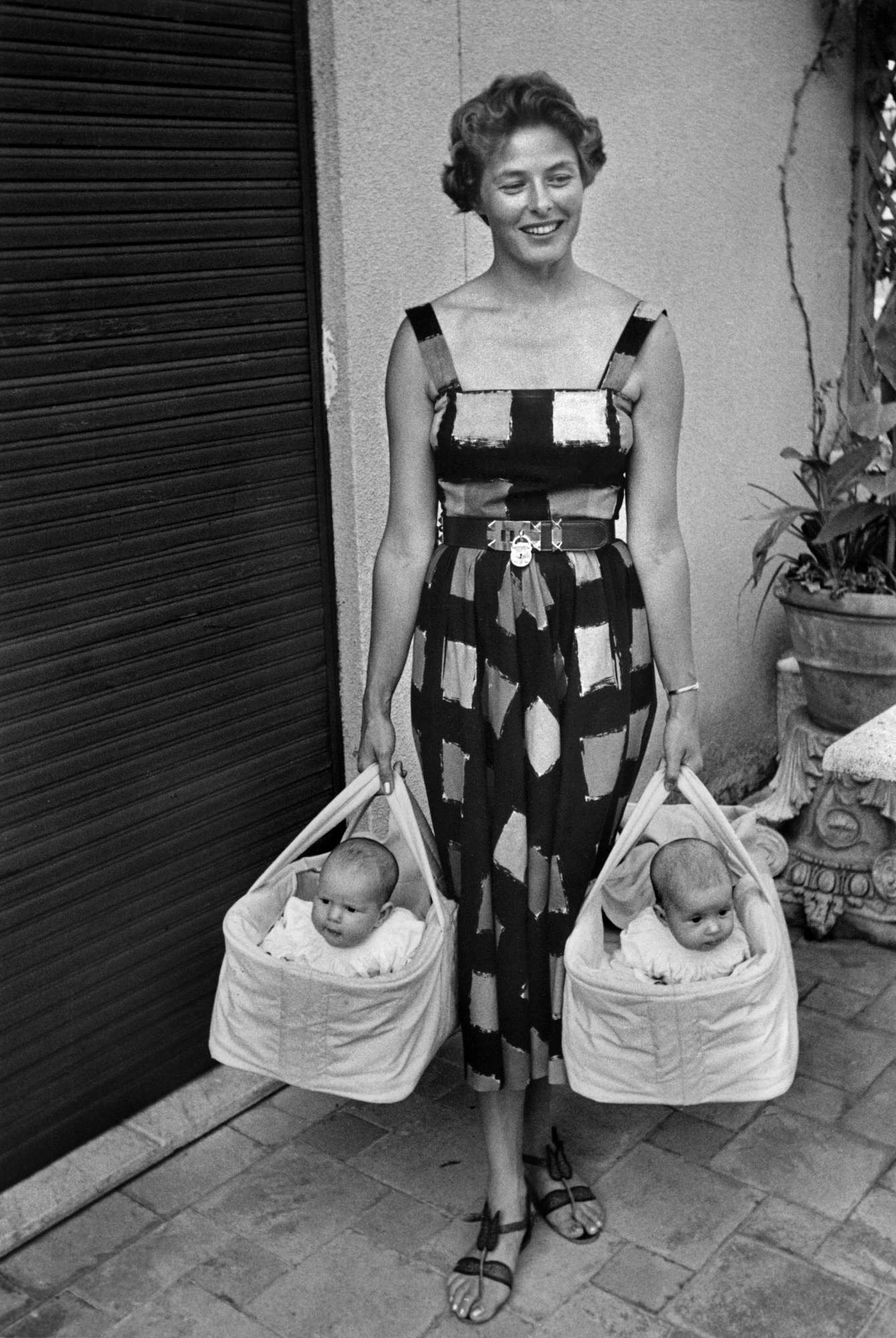

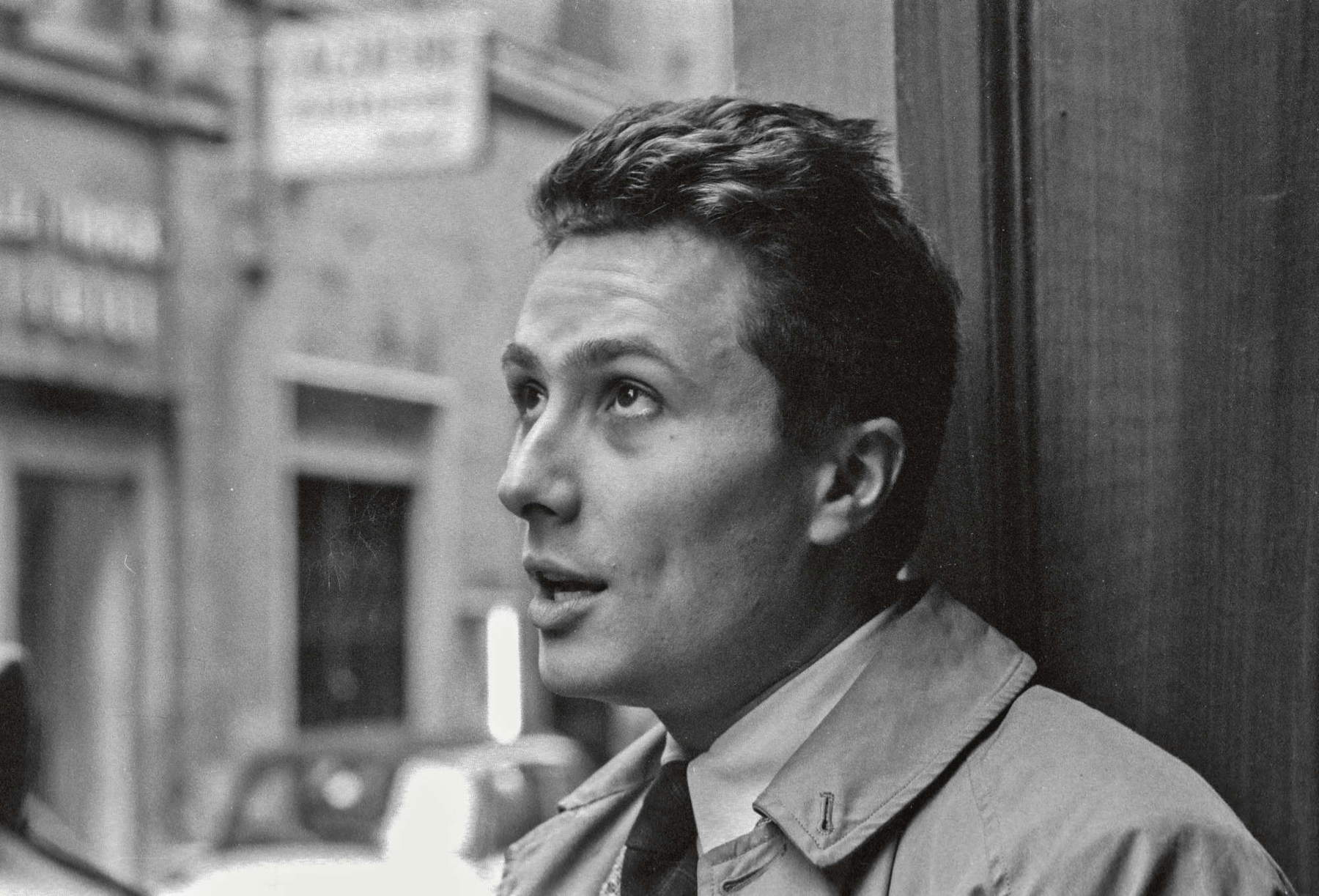

Giulia Niccolai

Giulia Niccolai Giulia Niccolai,

Giulia Niccolai, Giulia Niccolai,

Giulia Niccolai,

For what reasons in recent decades are the finds multiplying? It is not just luck, which also has its weight, but the consequence, if not of focused research, certainly of a radical change in the canons of attention. Our time has thrown the doors wide open to new points of view, giving space to worlds less or never represented. It is no coincidence that many rediscoveries have involved women, or in general areas of humanity that until now were excluded from the gaze (wonderful example are the images of Casa Susanna that Finestre Sull’Arte discussed here). But it is not only a matter of gender: the stimulus to greater cultural inclusion forces us to reread the past with broader criteria of analysis, which retrace the narrative according to the point of view of all the protagonists. Is there an ethical motive, then? I think it is also due to a practical need: we have glimpsed a variety of possible narratives and an infinite panorama of content to be developed. And in our age of creators, content is crucial, so if the insights offered by the present are not enough, the search turns to the past. This new interest touches all areas of culture, but photography in particular because it is the language that is easily understood, and because it admits-thanks to the weaning that social has accomplished-even nonprofessionals and thus multiplies the potential “rediscovered” by leaps and bounds.

A chapter so rich that it deserves a space of its own is that of “Vivian Maier-style” rediscoveries. The protagonists are always ordinary people, possibly women, with not particularly adventurous work, who have never shown such enthusiasm for art as to insinuate in family members or friends the doubt of being in the presence of a hidden genius. They all had a prolific photographic output, preserved with meticulous care while leaving a portion of negatives undeveloped, and maintained an irreproachable discretion that allowed them to remain undiscovered until an advanced age, if not beyond. Much has been written about the original, while I among the “replicas” have chosen to tell with strict consistency only those whose photos were discovered in travel bags.

As many as two are the custodian bags of Peggy Kleiber’s work: 15,000 photographs taken between the late 1950s and the 1990s. Kleiber was born in 1940 in Moutier, Switzerland, to a family that passed on to her a curiosity for culture and knowledge. Between poetry, music and literature, she then preferred photography as a means of expression, and soon decided to pursue it further by attending the Hamburger Fotoschule in 1961. Although from then on her Leica M3 would follow her on travels, family rituals and anniversaries, she would never be a professional photographer, becoming instead a teacher. Yet traits of a uniform project that accompanies her throughout her life are easily discernible in her photos, centering her research at the intersection of private and collective history.

Hers is a discreet gaze that has been able to capture moments of private and social life with never intrusive curiosity, and in more than fifty years she documents a rapidly changing world, with a particular focus on Italy, which she considered her home of choice, between Rome, Umbria, Tuscany, until she arrived in Sicily where she met Danilo Dolci portraying him in some precious and unpublished images during the “strikes to the contrary.”

After his death in 2015, the family rediscovered this heritage and decided to enhance it and make it public, among other things with an exhibition entitled Peggy Kleiber. All the Days of Life (Photographs 1959-1992) that was held at the Museo di Roma in Trastevere in 2023, curated by Arianna Catania and Lorenzo Pallini.

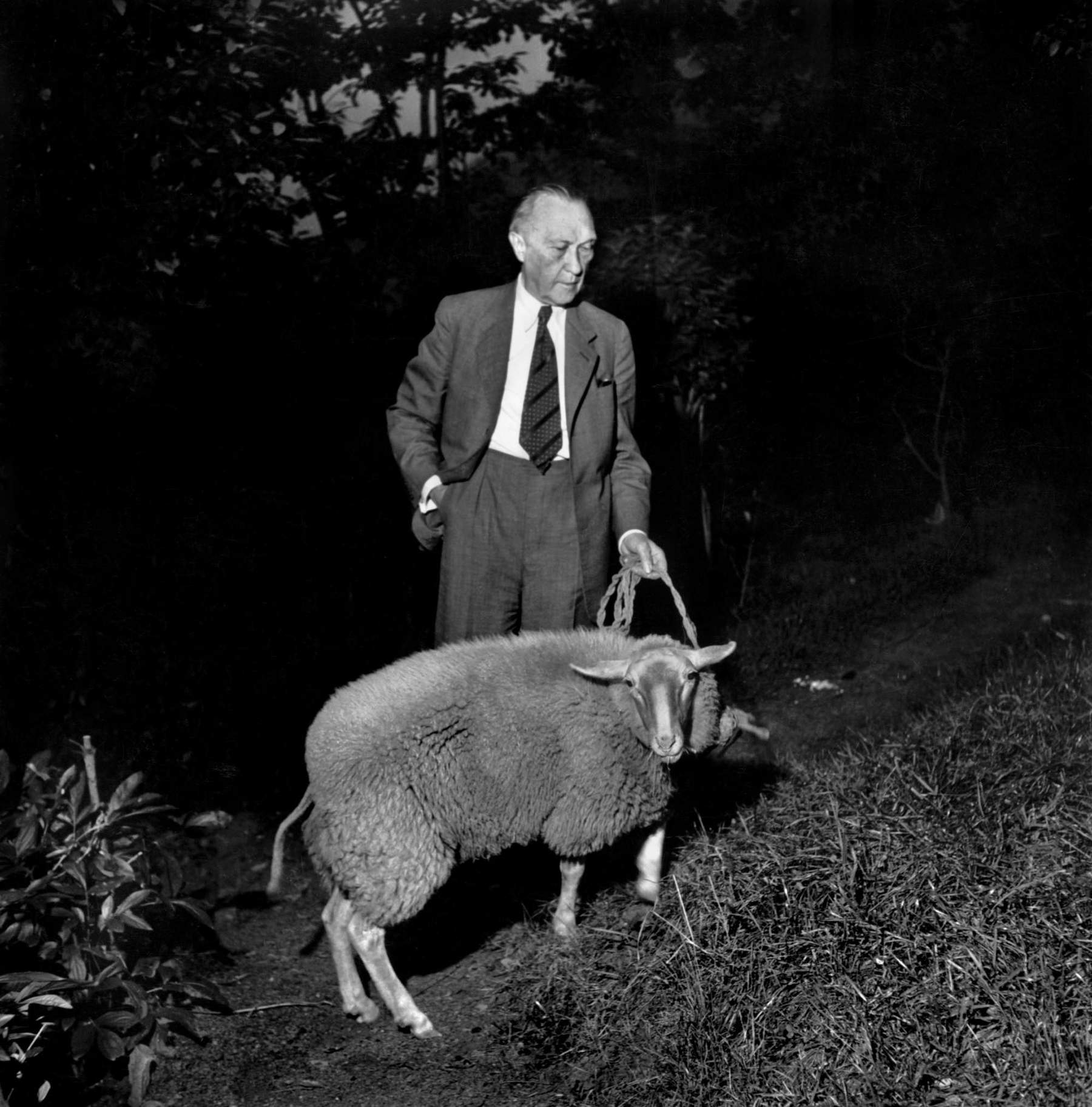

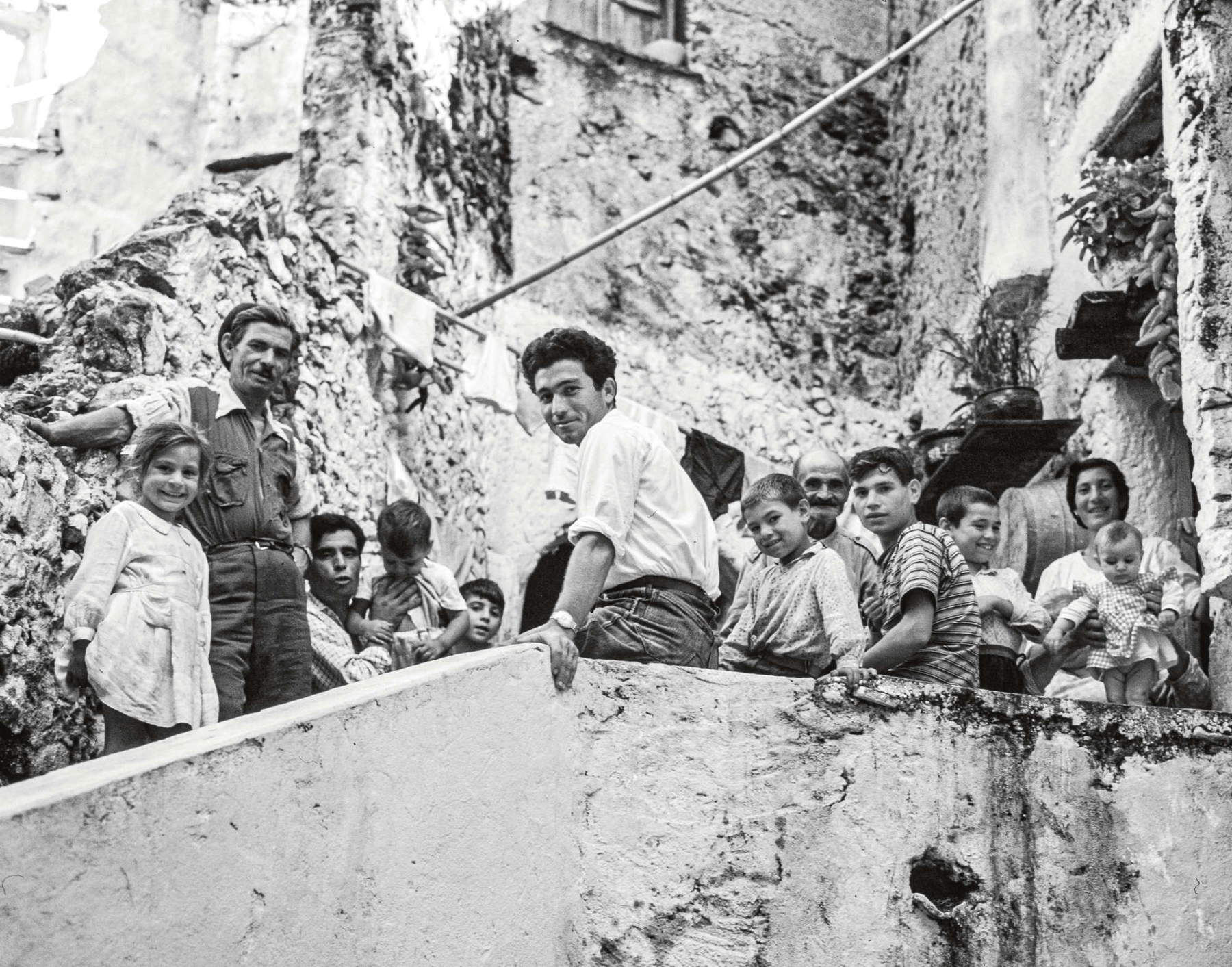

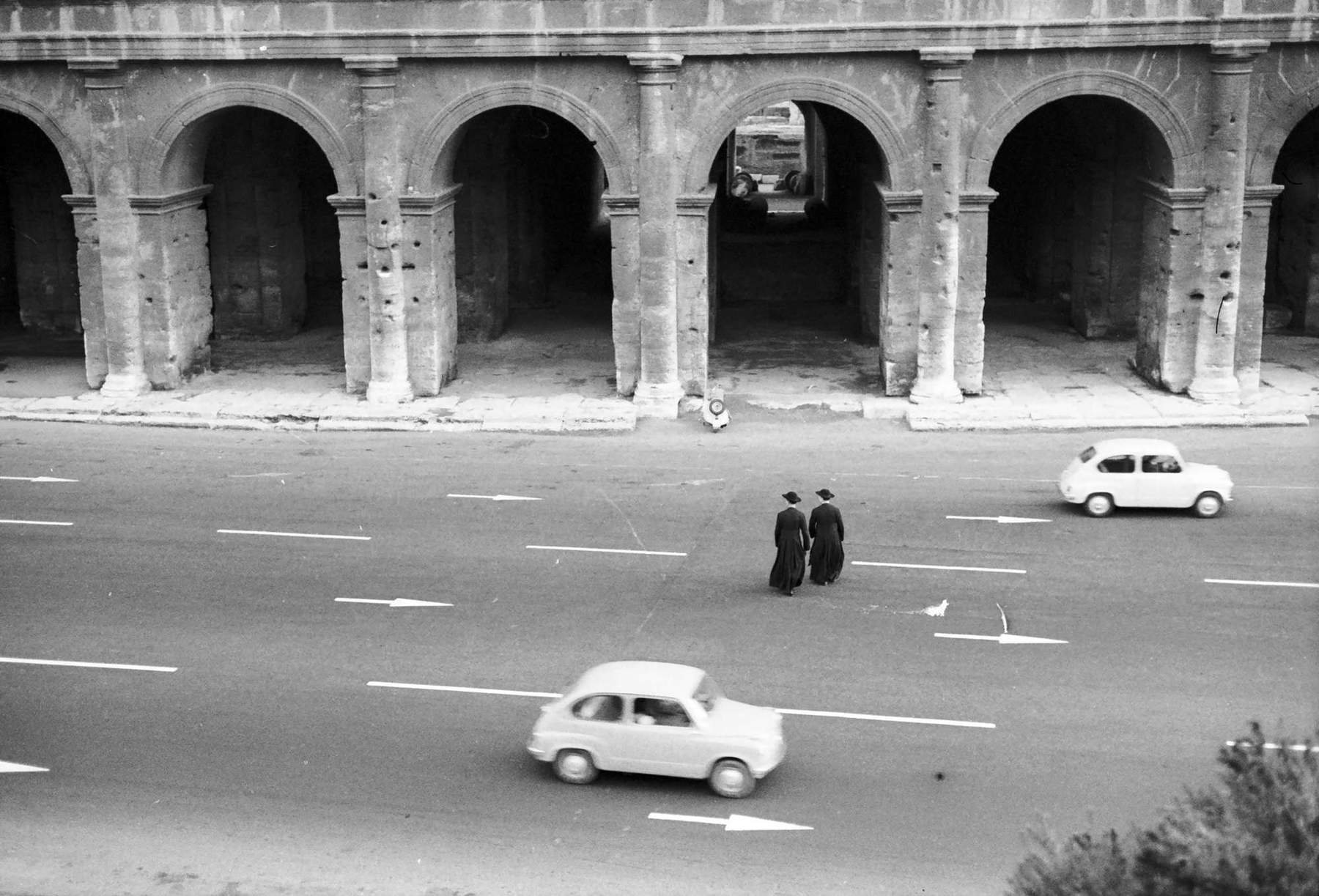

Peggy

Peggy Peggy

Peggy Peggy

Peggy Peggy

Peggy Peggy

PeggyMore blatant has been the rediscovery of Masha Ivashintsova. In 2017, nearly two decades after her death, her family launched a promotional campaign in which she was openly referred to as the “Russian Vivian Maier,” and which included a video recounting the fortuitous discovery of a suitcase full of her old, unprinted rolls of film. While the blatant coincidences with Maier’s story appear to be a mediocre marketing gimmick, her photos made it all the way to the International Center of Photography in New York, which in 2018 dedicated an exhibition to her, classifying her as a “street photographer.”

Her gaze certainly cannot compare to Vivian Maier’s originality, but certainly the overall body of photographs documents an important era in recent history: everyday life in St. Petersburg, then Leningrad, between 1966 and 1999, at the height of the Cold War. These were years when photographers were frowned upon, except those in the service of the authorities; their equipment and photos could easily be seized, and they arrested. Masha Ivashintsova, however, was part of the underground cultural movement that tried to keep alive a vision of the country different from that of official Soviet propaganda, and for this she was ostracized and locked up in a mental hospital. Her photos were long forgotten, which is perhaps why they survived the great changes in subsequent history.

I’m sure that after this reading many will have finally decided to tidy up the basement: who knows, maybe a suitcase full of photographs will come out of it, but even if it were a simple box it would be quite a discovery. Going through old albums is a very fun activity: trying to recognize relatives in photos, smiling at clothing or haircuts that are no longer in fashion, looking for details that no one had noticed before. But I also believe that the time is ripe to look with fresh eyes at what family photos can reveal to us about the history of our recent past. I have unearthed an entire album of images of a lavish early 20th century funeral, revealing of a culture of death that we have lost over time. But they could be ante litteram selfies, photos of a trip, those of an evening with friends. I invite you to make this effort: don’t stop at the content, but try to imagine yourself in the place of the person who was photographing: what did he or she choose, what did he or she leave out, what did he or she want to remain imprinted?

If you do not find a new Maier or a secret archive of a Gerda Taro, you can certainly discover and learn more about how those who came before you looked at the world.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.