When William Blake painted the ghost of a flea--after a vision

The work we discuss in this article can be seen at the exhibition Blake and His Age. Travels in Dreamtime, curated by Alice Insley, at the Reggia di Venaria Reale, Turin, through Feb. 2, 2025. For more info read here.

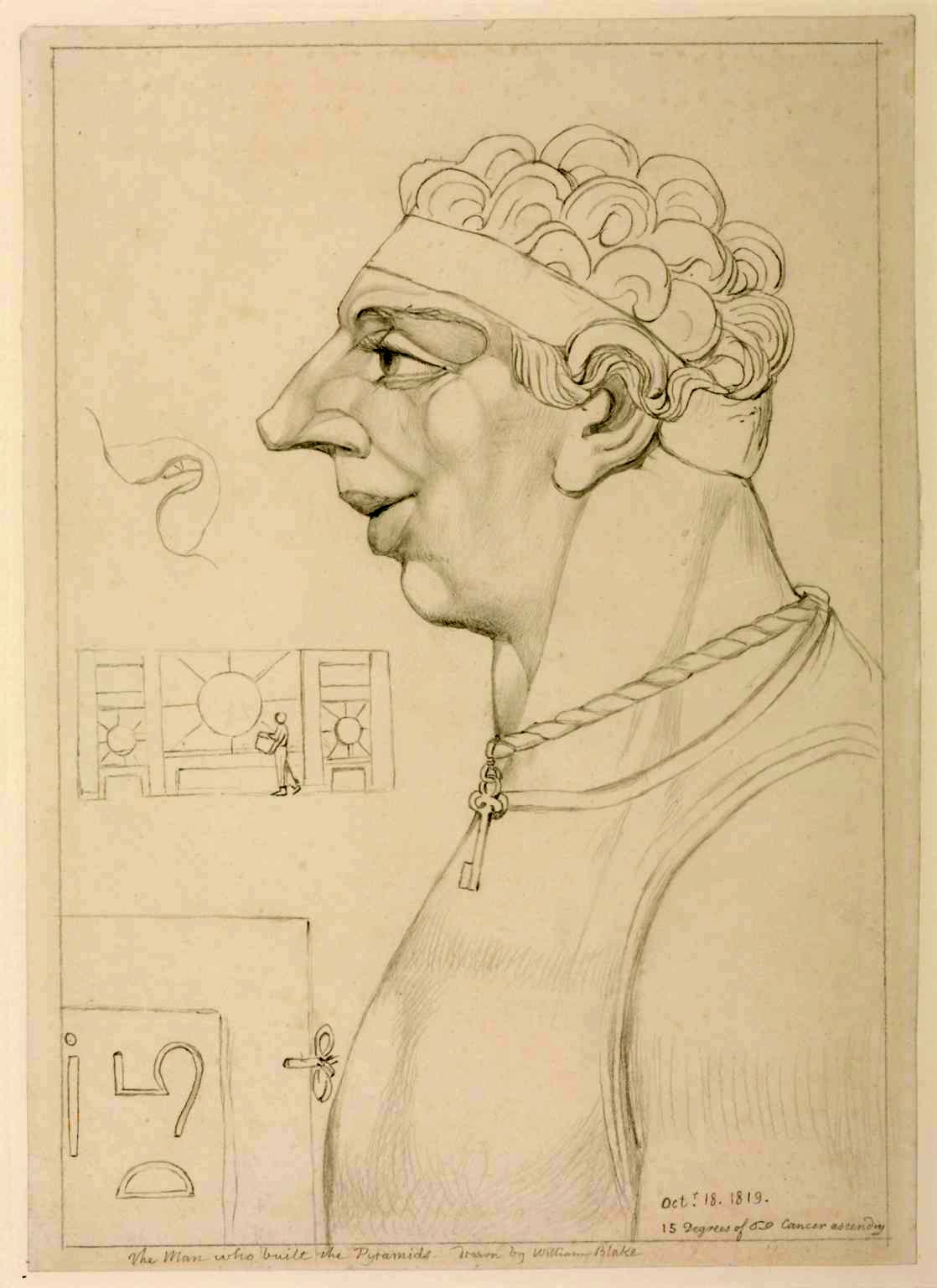

“Here he comes! With his eager tongue sticking out of his mouth, a cup in his hand to contain the blood, and covered with a scaly skin of gold and green”: this is how William Blake (London, 1757 - 1827) is said to have described one of the best-known characters in his artistic repertoire, The Ghost of a Flea, the protagonist of one of his famous miniatures made around 1819-1820. So, at least, he spoke of it according to the account of John Varley (Hackney, 1778 - London, 1842), an astrologer, painter, and friend of Blake for whom the London artist had painted a series of Visionary Heads that, according to Varley, were the result of direct visions on the part of the artist, in the sense that the young painter was truly convinced that these characters were manifesting themselves before Blake, inspiring his art.

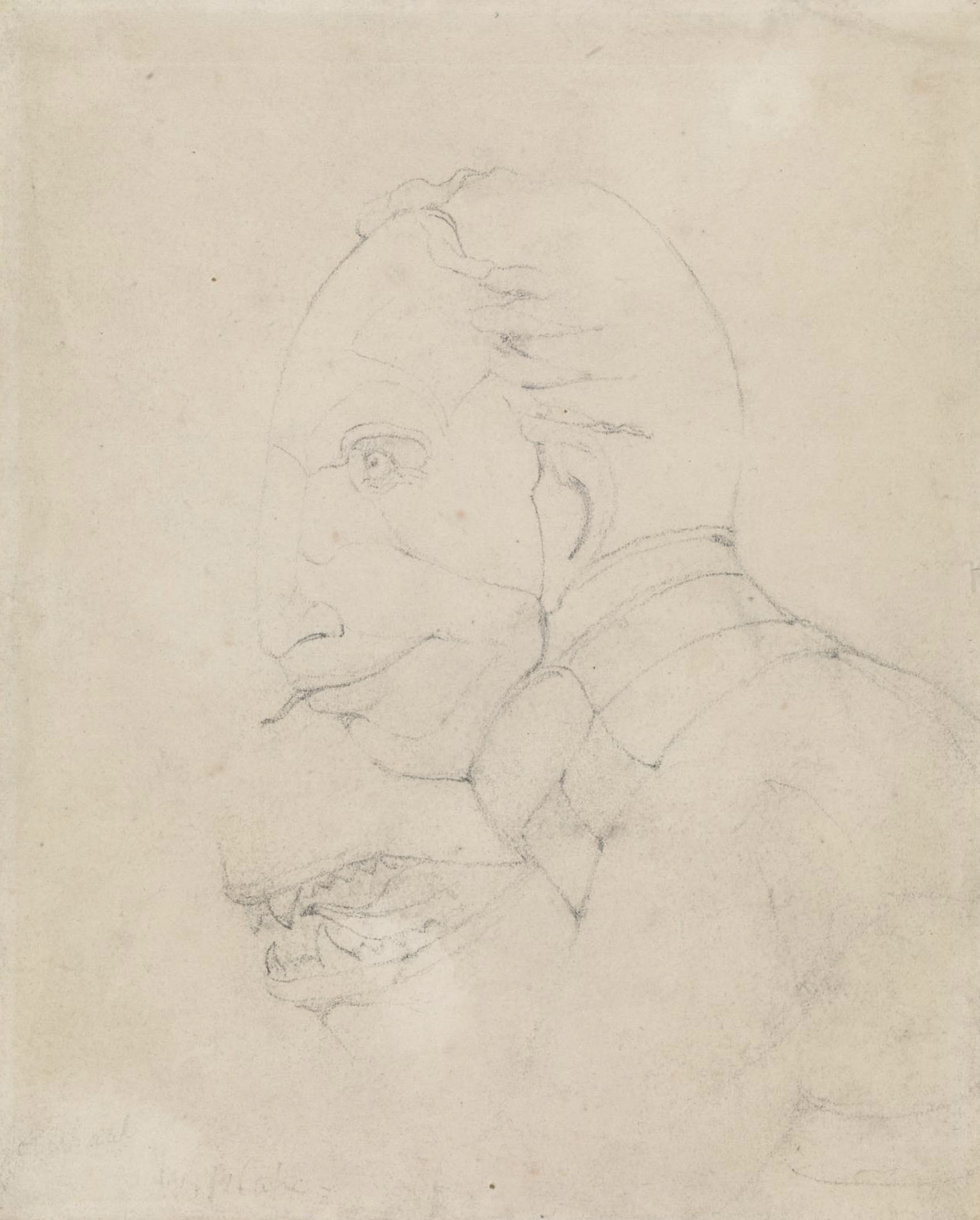

Varley and Blake had first met in 1818, and immediately the young man was fascinated by his colleague’s personality: he had apparently confided in Blake that he was firmly convinced that ghosts existed, but that he was dissatisfied that he could not see them. Blake, at the time, claimed to have had paranormal visions, and for this reason Varley was immediately interested in his stories. It was not long before the two began to hold séances, improvised at night, at Varley’s home. It was precisely during these “sittings” that Blake gave form to his own visionary Heads, and on one occasion the London painter would have a vision of the ghost of a flea, an apparition that would cause him much more excitement than usual, as he considered it something wonderful. The first time he had this vision, Varley recounts, Blake failed to depict the ghost, but the next time he was not unprepared. This is how Varley spoke of that evening: “Because I was anxious to make the most accurate investigation I could of the truth of these visions, the first time I heard of this spiritual apparition of a flea, I asked him if he could draw for me a picture of what he had seen. And he immediately said, ’I see it now before me.’ I then gave him paper and a pencil with which he drew the picture.... I felt convinced by the way he proceeded: it seemed to me that he had a real image in front of him, because at one point he stopped what he was doing, after which he began, on another part of the paper, to make a separate drawing of the flea’s mouth, a mouth that the ghost had opened, a circumstance that prevented him from proceeding with the first sketch ... until he closed it.”

It is likely that the drawing mentioned by Varley is a sheet, drawn in pencil and now in the Tate in London, where a monstrous head is seen and, separate, a mouth that looks like that of a reptile, very pronounced and elongated, with sharp teeth and a very long tongue: reminiscent of that of the xenomorph from Alien, wanting to find a contemporary comparison (not peregrine, since the influence of William Blake’s imagery on Ridley Scott’s cinema is well known). In contrast, the painting, a tempera on mahogany panel also preserved at the Tate, depicts the full-length ghost: it is an anthropomorphic spirit, with a nerveless body (muscle bundles appear in full view), depicted advancing while clutching a basket in its right hand. The monstrous face is stationary above a taurine neck: wings sprout above the ears, the eyes are large and wispy, the round head, small in comparison to the rest of the body, and contorted into a grimace of wrath, with a very long tongue sticking out of its mouth and reaching toward the contents of the vessel, namely the blood on which the flea feeds, according to Blake’s own account. The skin, which is dark, is scaly, the ghost has two braids falling down its neck, and the hands end in long, claw-like fingers. The flea ghost strides on a kind of stage, complete with an open curtain over a starry backdrop (we do not know why there are these stars, including a comet: perhaps, Blake wanted to pay homage to his friend’s astrological interests in this way).

Why was Blake excited in the face of a vision of a flea ghost? Almost everything we know about this fascination, whether real or presumed, we owe to Varley’s own reporting. It is therefore necessary to consider the special status that the artist, according to his friend, attributed to the tiny parasite. According to Blake, fleas were possessed by the souls of dead men who, in life, had been inordinately thirsty for blood. However, scholar Gerald Bentley, in one of his books on Blake, reports another, anonymous source that would report a discussion in which Blake himself would participate, who would relate a legend that the flea, when it was created, complained about its size: “At first I was supposed to be as big as an ox,” said the flea, “but then, when it was realized that I was so armed and so strong that, in proportion to my size, I would be too powerful a destroyer, it was decided not to make me any bigger than I am.”

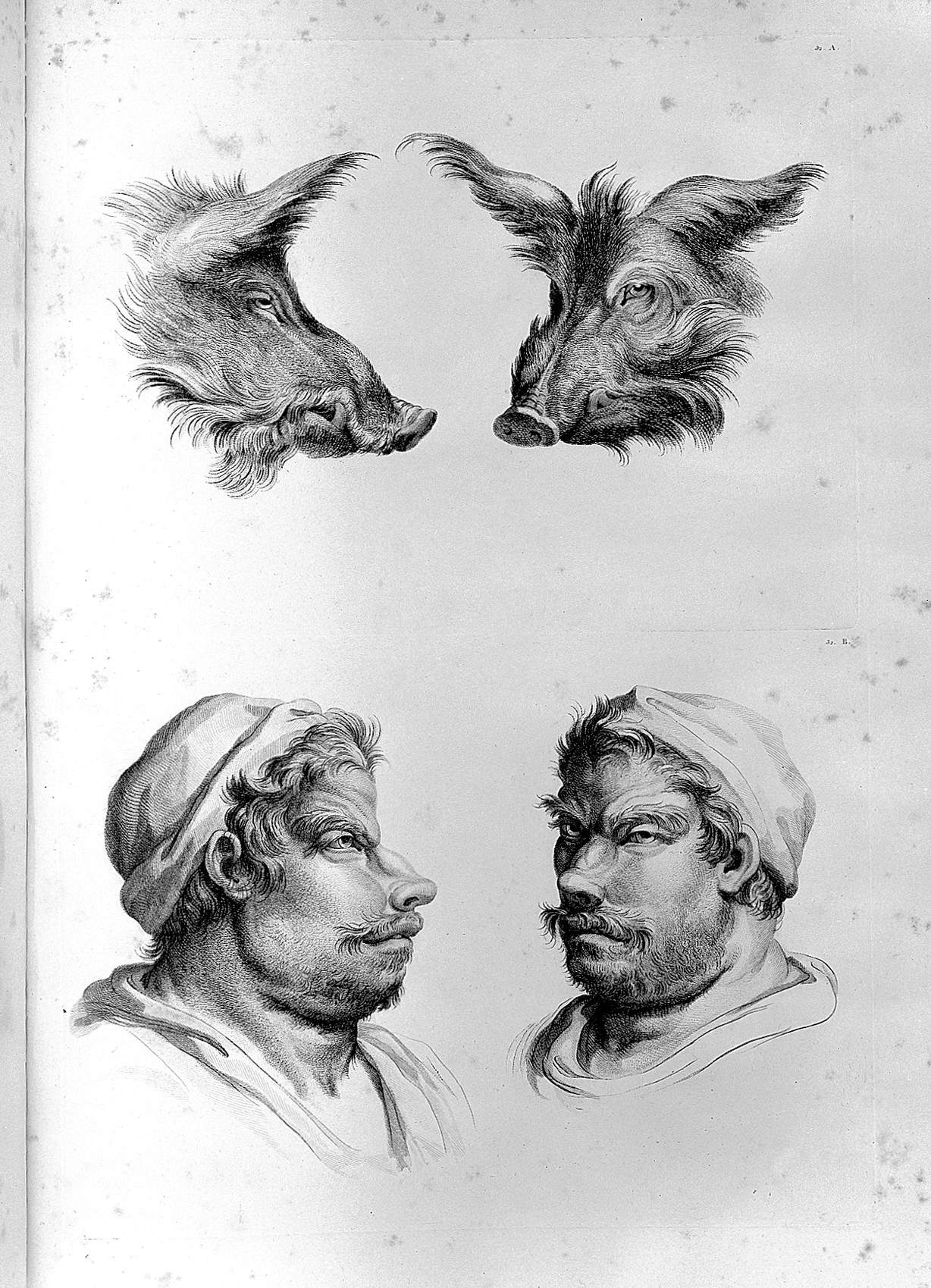

The interesting question is: Did Blake really have the visions he claimed to have? It is likely, scholar Alice Insley has written, that “Blake was deluding his young friend with imaginary apparitions.” It must be said, however, that biographer Alexander Gilchrist reports of a vision of a ghost (described as a “hideous and sinister, scaly, spotted, very frightful” figure), which Blake is said to have had in 1790, thus long before he met Varley. Surely, The Flea Ghost cannot be the product of mere visionary imagination: it is likely that Blake was well aware of some precise iconographic sources that may have suggested to him his flea spirit. Scholar Sibylle Erle, for example, has related this work of Blake’s to Giovanni Battista della Porta’ s Physiognomy of Man and the later physiognomic studies of Charles Le Brun , which, like those of the Neapolitan scientist, compared the connotations of certain human types with the snouts of various animals. These are works that may have impacted the analogies between humans and animals that, after all, are part of Blake’s vocabulary. Perhaps with a specific purpose, Erle argues: “The reason he gave voice to the flea,” in his view, “is that he wanted to make physiognomists and astrologers think about the consequences of character readings for the identity of any being. Blake’s flea, in other words, can never be caught. It resists both its creator and its interpreters.”

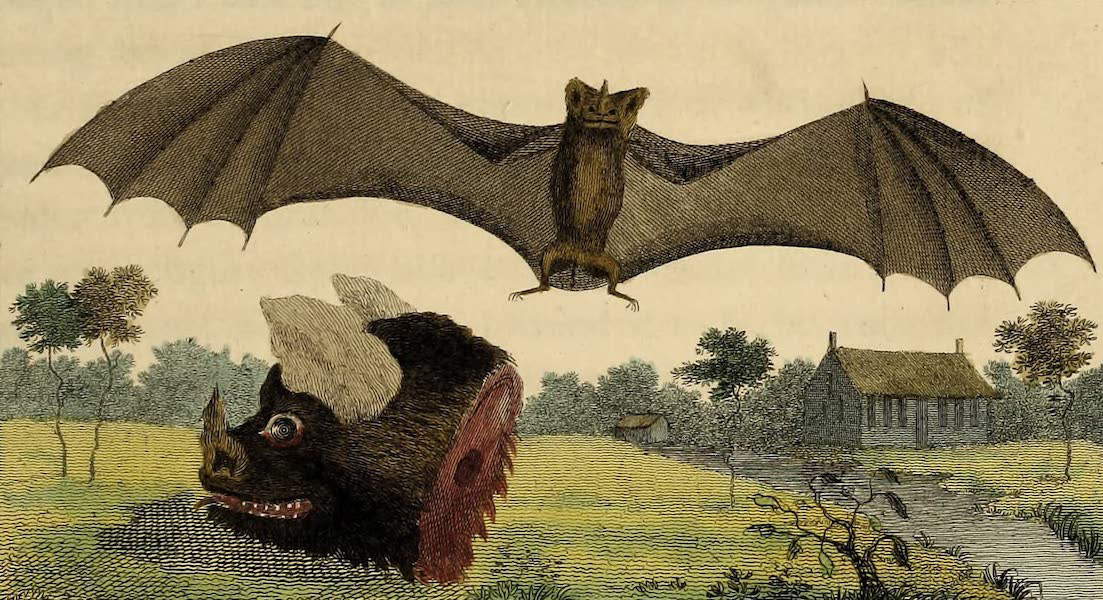

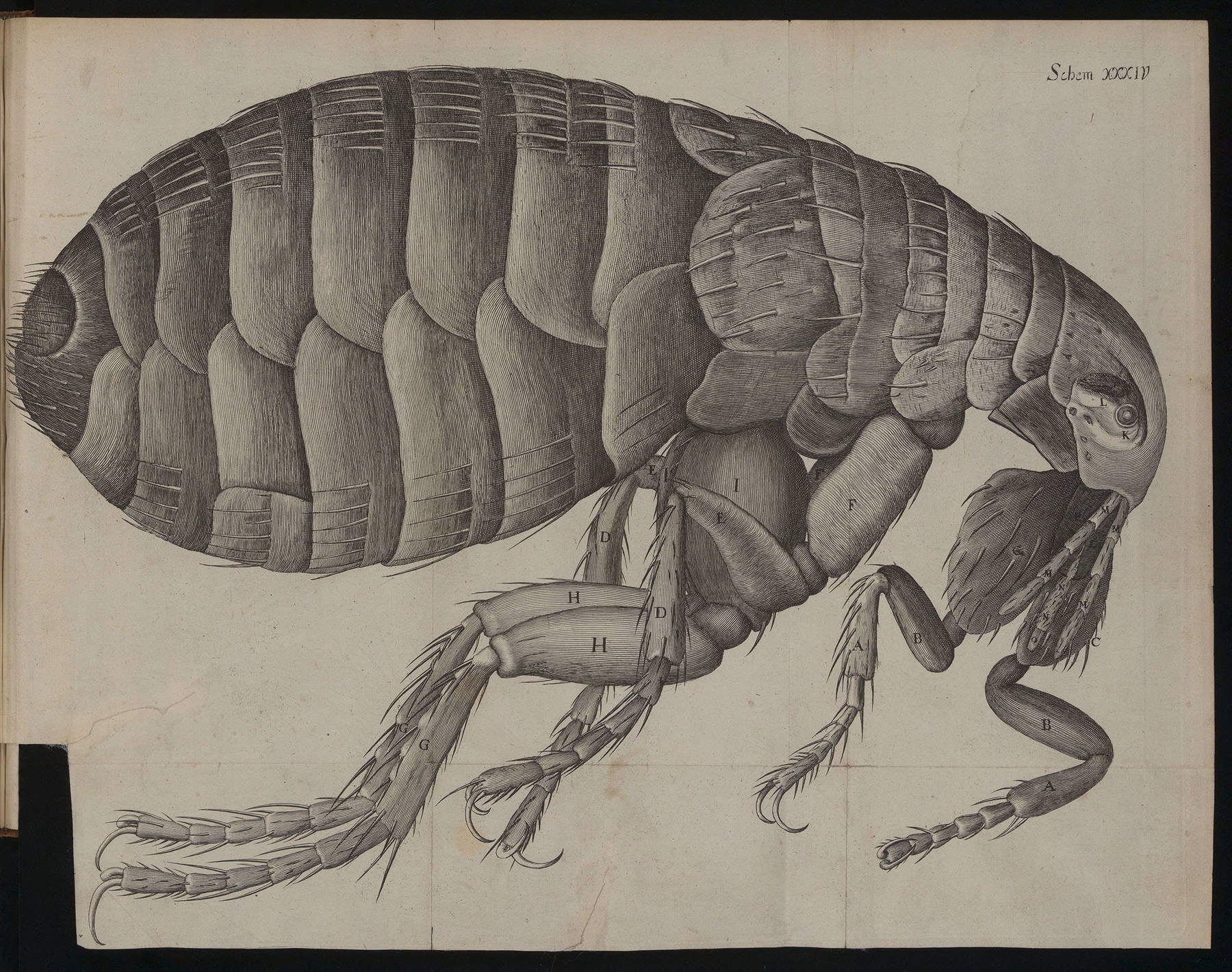

Other sources might have been Johann Heinrich Füssli’s The Nightmare , or even images of bats and vampires such as The Vampire or the Ghost of Guiana that the Dutch writer and military man John Gabriel Stedam includes in his book The Narrative of a Five Years Expedition against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam, published in London in 1796 (moreover, it is not to be excluded that, on the description of the flea as a bloodthirsty soul, the whole folkloric imagery related to vampires may have had some effect: literature on vampirism, at the time, was in its infancy). There was also no shortage of depictions of fleas under the microscope, published since the seventeenth century: one example is the one included in Robert Hooke ’s Micrographia of 1665 (the first treatise in history to illustrate objects observed under a microscope: it is here, moreover, that the term “cell” is used for the first time, albeit with a different meaning than today).

![Giovanni Battista della Porta, Physiognomy of Man (1586 [1644]) Giovanni Battista della Porta, Physiognomy of Man (1586 [1644])](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2024/2894/giovanni-della-porta-fisiognomica-dell-uomo.jpg)

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.