When was the great Raphael Sanzio really born and when did he disappear?

Today many celebrate the birthday (or the anniversary of the death) of one of the greatest painters in the history of art, Raphael Sanzio (Urbino, 1483 - Rome, 1520): the date of his birth is traced by most to April 6, 1483. And moreover, according to many, April 6 was also the day on which the artist disappeared, in the year 1520. It is worth delving a little deeper into this question, in the sense that much has been discussed about the two dates: an argument that on the surface may seem insignificant, is instead of great interest because it makes us realize how difficult the study of sources is and how little certainty we have in many cases, when we study art history.

Regarding the date of his birth, there are basically two sources: Giorgio Vasari (Arezzo, 1511 - Florence, 1574) and Pietro Bembo (Venice, 1470 - Rome, 1547). In his celebrated Lives, Giorgio Vasari writes that: “Raphael was born, therefore, in Urbino, a city very well known in Italy, in the year 1483, on Good Friday at three o’clock at night.” Good Friday in 1483 fell on March 28. The scholar Pietro Bembo, on the other hand, was the one who composed theepitaph for the painter, writing, in Latin: “Quo die natus est, eo esse desiit VIII Id. Aprilis MDXX,” meaning “He passed away on the same day on which he was born, on the eighth day before the ides of April 1520 (that is, April 6, 1520),” and the date of his passing is placed, precisely, on April 6, 1520. What we cannot know, however, is what Bembo meant by “quo die” (“the same day”), that is, whether “April 6” or “Friday.” Since, however, April 6 in 1520 fell on a Tuesday, most have interpreted Bembo’s phrase as referring to the number, April 6, rather than the day of the week: hence the tendency to shift Raphael’s date of birth to April 6, 1483. By the way: let us specify that not everyone agrees in attributing the epitaph to Pietro Bembo. Since 1911, in fact, the name of Antonio Tebaldeo (Ferrara, 1462 - Rome, 1537) has been circulating, proposed by Domenico Gnoli (in an article that appeared in the Giornale d’Italia) in place of that of Bembo, which was indicated, for the first time, again in Giorgio Vasari’s Lives: the situation is therefore further complicated. It must be said, however, that there are still many who lean toward attributing the epitaph to Bembo.

|

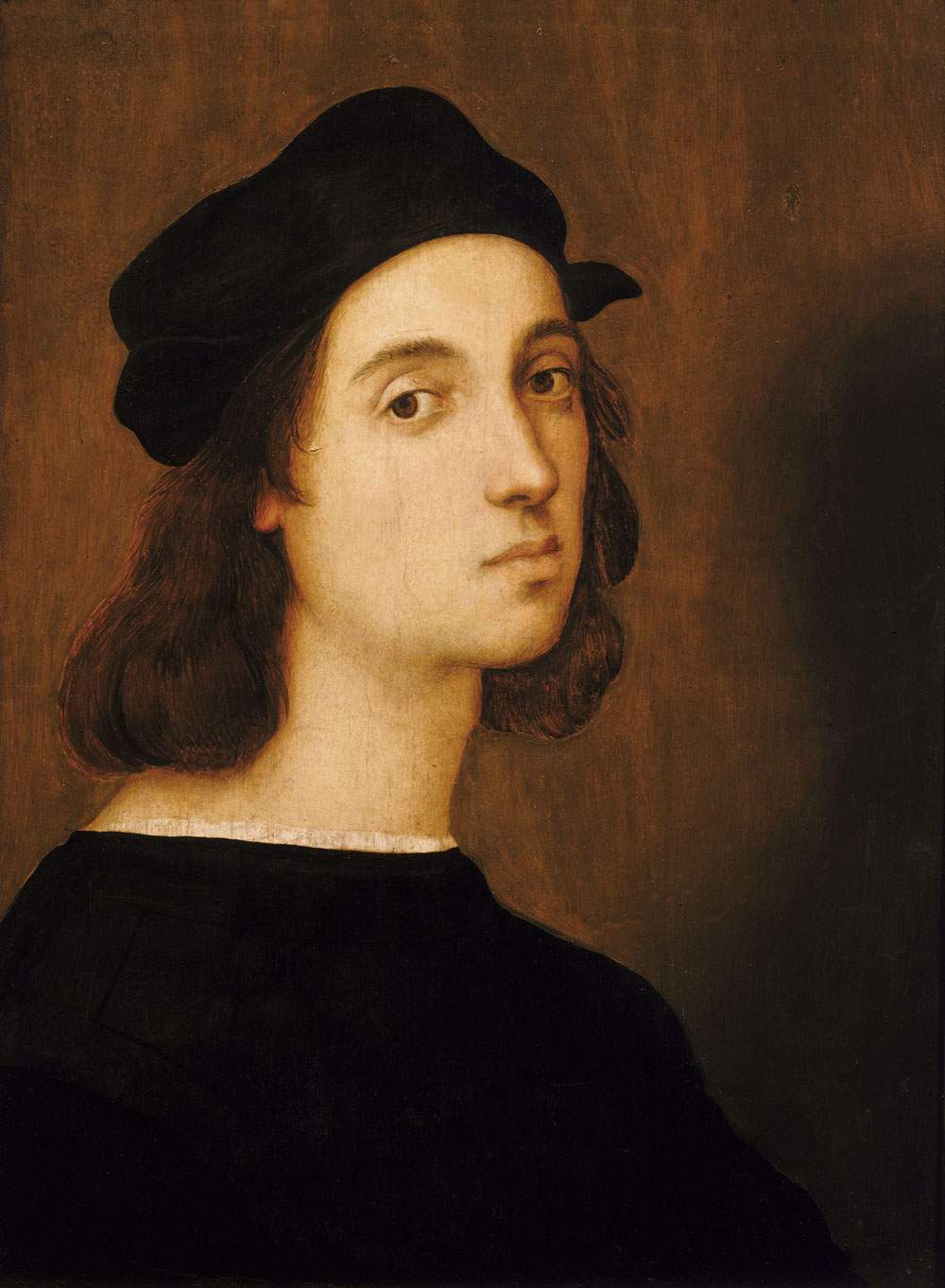

| Raphael Sanzio, Self-Portrait (c. 1504-1506; oil on panel, 47.5 x 33 cm; Florence, Uffizi Galleries) |

What do we know instead about the date of his disappearance? Several sources, including a letter from Count Pandolfo Pico della Mirandola sent to Isabella d’Este on April 7, set the date of the artist’s demise at Good Friday 1520 (so wrote the nobleman: “ala Excellentia vostra la quale per hora non sarà advisata d’altra cosa che de la morte di Raphaello d’urbino, quale morite la notte passata, che fu quella del venerdì santo, lasciando questa corte in grandissima et universal mestitia per la perdita de la speranza di grandissime cose che si expettavano da Lui”), which that year fell on April 6. The most discussed source (because it also provides the time), however, is another letter, from the well-known art collector Marcantonio Michiel (who, moreover, was only a year younger than the artist), where it is written that “on Good Friday night, sabbath coming, at hore 3 morse il gentilissimo ed eccellentissimo pittore Raffaello di Urbino.” Thus, it is likely that Raphael actually passed away on Friday evening, because assuming that Michiel reasons with the calculation of hours on the basis of sunset as was the custom at the time, the third hour of the night would correspond to the present 21 or 22 in the evening.

The discourse on dates, however, played an important role in the mythologizing of the artist, who even when he was alive, given the great refinement and celestial grace of his painting, was considered a divine painter, endowed with almost supernatural skills and abilities. It was therefore natural that the disappearance (and birth) on Good Friday should go to form a founding part of the Raphael myth: it was a way of relating the figure of the painter to that of Christ. This element, this comparison, is enough to show how far Raphael’s myth had gone.

Reference bibliography

- Giorgio Vasari, Le vite dei più eccellenti pittori, scultori e architetti, Florence, Giunti, 1568

- Pietro Odescalchi, Istoria del ritrovamento delle spoglie mortali di Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino, Rome, Boulzaler, 1833

- Alessandro Zazzaretta, On the Date of Raphael’s Birth in L’arte. Bimonthly journal of medieval and modern art history, Volume 23, 1920

- Giuseppe Rossi, La rinascenza dell’arte del Piceno : Raffaello e Bramante, Macerata, Bisson & Leopardi, 1925

- Domenico Gnoli, The Rome of Leo X : paintings and original studies, Rome, Hoepli, 1938

- Claudio Strinati, Raffaello, Florence, Giunti, 1995

- Elena Capretti, Raffaello, Florence, Giunti, 1996

- Stefano Pagliaroli, L’epitaffio di Pietro Bembo per Raffaello in Pietro Bembo e l’invenzione del Rinascimento, exhibition catalog (Padua, February 2 - May 19, 2013), Padua, Marsilio, 2013

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.