On November 10, 1816, a solemn wedding was celebrated in Vienna between the Emperor of Austria, Francis I (Florence, 1768 - Vienna, 1835), then forty-eight years old, and Princess Caroline Charlotte Augusta of Bavaria (Mannheim, 1792 - Vienna, 1873), twenty-four years younger: the ceremony was also attended by a delegation from Venice, which after the fall of Napoleon had become part of the Lombardo-Veneto Kingdom, directly dependent on the Austrian empire. The mission of the Venetian delegation, composed of four distinguished citizens, also had a political purpose: in fact, the emperor had stipulated that each province of the empire should give a substantial cash tribute as a gift for the newlyweds. Even the Venetian section of the Kingdom had to contribute, with a decidedly substantial sum for the coffers of the former Republic of Venice. At the time, the Veneto was in fact going through a serious economic crisis: the stagnation that, in Europe, followed the decade of the Napoleonic wars, caused a decrease in agricultural and industrial production with the consequent collapse of agricultural prices, and resulting in reduced wages, impoverishment of many people, and bankruptcy of companies and banks. Venice therefore had a major problem to solve: a further tax would undermine the first tentative attempts at recovery.

The solution to the dilemma was devised by Count Leopoldo Cicognara (Ferrara, 1767 - Venice, 1834), at the time president of the Academy of Fine Arts in Venice, a refined intellectual and, above all, a character who enjoyed great international prestige and high regard at the Austrian court. The idea was as simple as it was ingenious: to ensure that the emolument could be converted, at least in part, into works of art to be given to the newlyweds, for their Viennese apartments. Cicognara would thus have achieved a twofold positive effect: on the one hand, freeing Venice from the hefty disbursement. On the other, to circulate the names of the best Venetian artists of the time in Vienna, so that wealthy local patrons might have noticed them: a kind of publicity investment. Thus, the president, in January 1817, took pen and paper and immediately wrote to his friend Antonio Canova (Possano, 1757 - Rome, 1822), at that time the most famous, celebrated and in-demand artist in the world, to involve him in the project: “I must make you a very great confidence: know that all the Provinces are obliged to make the Emperor a regallo for the occasion of the wedding and that the section of the Lombard Kingdom will already give for this object 30 thousand zecchini. The Venetian section will give what it can. I would not then want it to give all money, and I would like to disburse 10 thousand zecchini in so many works of brush and scarpello all Venetian. I will not forget Hayez certainly and Rinaldi, and all the others who are capable of work here. But all this is worth nothing if for the first part of this project there is no work of yours.” Cicognara, thanks in part to his relations with the imperial chancellor Klemens von Metternich (Koblenz, 1773 - Vienna, 1859), succeeded without too much difficulty in convincing Austria of the goodness of his intentions, not least because the Austrian treasury had already been plentifully replenished with tributes paid by the Lombards and the Austrians themselves. The success of the project, however, depended on the presence of Canova: Austria would probably not have agreed to it unless it was sure that, among the works the sovereigns would receive, there would also be a sculpture made by the hand of the most illustrious genius of the time.

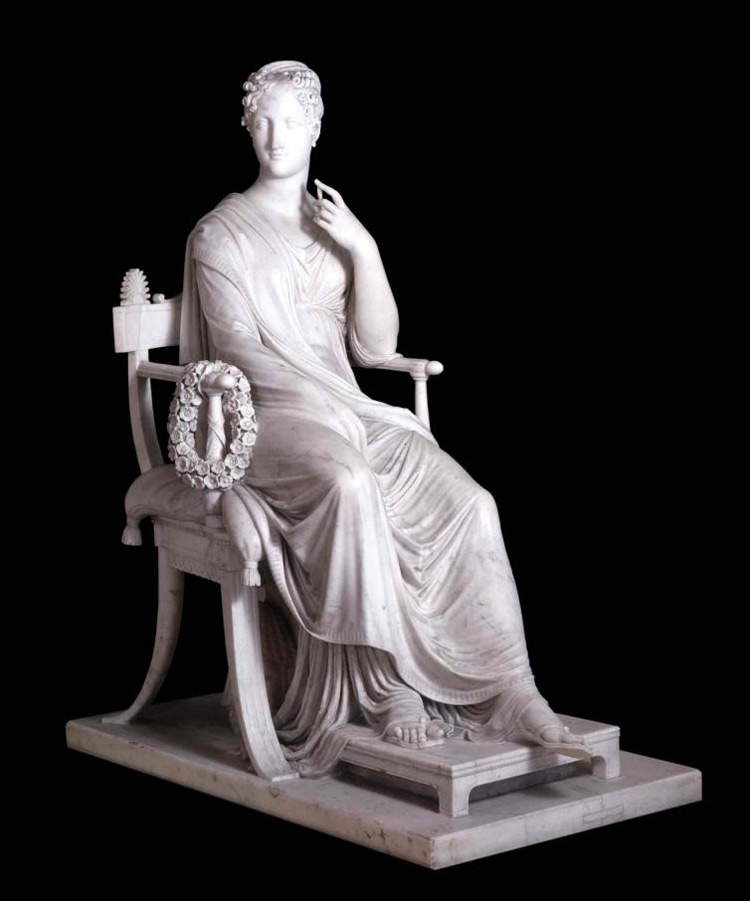

But Cicognara also had clear ideas about achieving this goal. This is how the letter of January 1817 continues, “Here it would take the security of a statue of yours, and it would be the Polynnia that could also be baptized for the Muse of History. Whatever the commitments, any other could be arranged later, but supposing my project you would be required to finish as promptly as you are permitted a statue for your Province which would make formal application to you to offer it to the Emperor. To such an unforeseeable case there is no answer. I keep in the thread of my ideas three thousand zecchini destined for this work to which little of your labor is lacking. So beginning by sending without much delay one of your works may later come the remainder as an accessory, and give time. I need a very prompt reply, for in Vienna yesterday it was written by the governor to whom my idea was very much liked, and if it is accepted, as I am almost sure it will be, I must be in measure with all my ideas to give effect to everything as promptly as possible. You see that I no longer sleep until this thing is exhausted.” The Canova sculpture Cicognara had been thinking of was the Musa Polimnia, the muse of dance and sacred song, which had been commissioned in 1809 from the Possagno artist by Elisa Baciocchi, Grand Duchess of Tuscany and sister of Napoleon (the Canova muse had, by the Grand Duchess’s firm wishes, her features): after Napoleon’s fall, Elisa Baciocchi, no longer able to pay for the work, had given it to the Bolognese nobleman Cesare Bianchetti, who then gave it up (also convinced by Cicognara) to turn it over to the Accademia in Venice. Once back in possession, Canova took care to slightly modify the muse’s face so that it would appear more idealized.

|

| Francesco Hayez, Portrait of the Cicognara Family (1816-1817; oil on canvas; Venice, Private Collection) |

|

| Antonio Canova, Musa Polymnia (1812-1817; marble; Vienna, Hofburg, Kaiserappartements) |

Having convinced Canova, it was necessary to determine who should take part in the project. Cicognara, in the aforementioned letter, showed that he already had at least a couple of names in mind: Francesco Hayez (Venice, 1791 - Milan, 1882) and Rinaldo Rinaldi (Padua, 1793 - Rome, 1873), aged twenty-six and twenty-four, respectively, and identified therefore as the two most promising Venetian artists, the former in painting and the latter in sculpture. The two young men would be joined by a group of artists in which there were more experienced authors, almost all between the ages of thirty and forty, and who were therefore seeking affirmation. For painting, in addition to Hayez, Lattanzio Querena (Clusone, 1768 Venice, 1853), Liberale Cozza (Venice, 1768 - 1821), Giuseppe Borsato (Toppo, 1770 Venice, 1849), Giovanni De Min (Belluno, 1786 - Tarzo, 1859) and Roberto Roberti (Bassano del Grappa, 1786 - 1837) would have participated. For sculpture, Canova and Rinaldi were to be joined by Angelo Pizzi (Milan, 1775 - Venice, 1819), Luigi Zandomeneghi (Colognola ai Colli, 1778 Venice, 1850), Antonio Bosa (Pove del Grappa, 1780 - Venice, 1845) and Bartolomeo Ferrari (Marostica, 1780 - Venice, 1844), while Giuseppe De Fabris (Nove, 1790 - Rome, 1860) was to be added later. The artists’ paintings and sculptures would later be joined by works of goldsmithing and luxury craftsmanship.

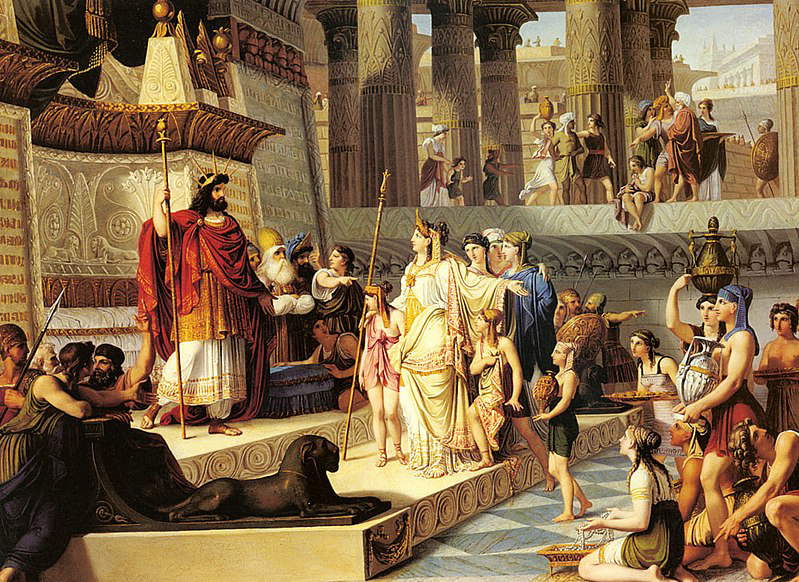

The events of what would go down in history as theHomage of the Venetian Provinces have been punctually reconstructed in a recent essay by art historian Roberto De Feo, published in the catalog of the exhibition Canova, Hayez and Cicognara. The Last Glory of Venice (at the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice from September 29, 2017 to July 8, 2018), which for the first time, exactly two hundred years later, brought back to the lagoon the works that Cicognara had gathered for shipment to Austria. The president of the Academy of Fine Arts was the skillful director of the whole operation: the works sent to Francis I and Caroline Carlotta Augusta were meant to prompt, as scholar Fernando Mazzocca has written, “reflection on the prospects of good government, in continuity with the age of reforms linked to enlightened despotism.” Thus, for the paintings part, among the first to set to work was Hayez, who dealt with the Purification of Time made by Hezekiah: the protagonist is Hezekiah, king of the kingdom of Judah whose merciful deeds are recorded in the Bible, and who in the painting is caught in the act of making sacrifices in honor of God, thus strengthening the covenant between God and the people of Israel. It is a work that still reveals a clear neoclassical approach, and the same is true of the painting by Lattanzio Querena, who was commissioned to paint Moses asking Pharaoh for freedom for Israel, with the biblical prophet who, with an imperious gesture and at the head of his people, asserts his demands in the presence of the oppressor. To Liberale Cozza fell the task of painting The Return of Ahasuerus in the boarding school hall, which De Feo calls “the most mysterious painting in the Homage,” because it has never been traced, and because it has never been the subject of in-depth study. The theme refers to a biblical episode in which the Persian king Ahasuerus, upon entering a banquet hall, finds his wife Esther, a Jewess, together with the evil minister Aman: the queen had in fact discovered a plan by Aman to destroy her and her people, and Ahasuerus ordered the minister to be put to death. The point of the work was thus to demonstrate to the Austrian rulers the need to have good advisers and to punish bad ones. The last of the four paintings with biblical subjects had been assigned to Giovanni De Min: the theme chosen was The Queen of Sheba before King Solomon, a symbol of conciliation.

The batch of paintings was completed by four views of Venice, a genre particularly beloved outside the Veneto region, on which Cicognara had also wanted to graft topical political themes, causing Giuseppe Borsato and Roberto Roberti to engage in the creation of the “four perspectives of Venice with festivities that occurred during the emperor’s stay.” Borsato thus produced a View of St. Mark’s on the day that the Venetian Provinces took the oath of allegiance to His Imperial Majesty and a painting depicting the Landing of the Bronze Horses at the Piazzetta of St. Mark’s, another tribute to Austria who was being celebrated as the one who had brought back to Venice the horses of St. Mark ’s stolen by Napoleon during the occupation of the city (an event which, for Venice, had been a huge snub). Borsato, moreover, also designed the table, which was made by Murano artisan Benedetto Barbaria. Instead, Roberti painted The Passage of the Imperial Court under the Rialto Bridge, celebrating Francis I’s entry into Venice on October 31, 1815, and a View of the riva degli Schiavoni as far as the Giardini Reali, a painting seemingly devoid of historical references, but capable of representing “one of the clearest recollections to the sovereign eye and mind,” as the description of the painting in the volume that accompanied the Homage of the Venetian Provinces read.

|

| Francesco Hayez, Purification of Time Made by Hezekiah (1817; Persenbeug-Gottsdorf, Persenbeug Castle) |

|

| Lactantius Querena, Moses asks Pharaoh for freedom for Israel (1817; Persenbeug-Gottsdorf, Persenbeug Castle) |

|

| Giovanni De Min, The Queen of Sheba before King Solomon (1817; location unknown) |

|

| Giuseppe Borsato, View of St. Mark’s on the day the Venetian Provinces took the oath of allegiance to His Imperial Majesty (1817; Venice, Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia, Prints and Drawings Cabinet of the Correr Museum) |

|

| Roberto Roberti, View of the riva degli Schiavoni as far as the Giardini Reali (1817; Artstetten Castle Collection, Lower Austria) |

Of a different sign, however, were the sculptural groups, with which Cicognara had wanted to imply “another symbolic message,” explains De Feo, “emphasizing the temperance of the sovereigns in the reference to the generous and prudent education of the young, capable of rooting the highest sentiments such as love of country.” In this sense, therefore, the mythological themes of the sculptures, all depicting young men being educated, appear very clear: Rinaldi sculpted The Centaur Chiron teaching Achilles to play the zither, Angelo Pizzi was assigned The Oath of Hannibal (where Hannibal as a child is urged by his father Hamilcar to swear eternal hatred to the Romans, bitter enemies of the Carthaginians), a work later completed by Bartolomeo Ferrari due to Pizzi’s passing, while Ferrari engaged in a subject identical to the one that fell to Rinaldi, producing Chiron teaching Achilles in music (which replaced, as will be seen in a moment, Rinaldi’s work, which did not leave for Vienna). Zandomeneghi and De Fabris, on the other hand, worked on two large Classical vases, which reproduced the shape of the Borghese Vase (a large Pentelic marble crater from the first century B.C., now in the Louvre) and were decorated with nuptial themes: the Aldobrandine Wedding for Zandomeneghi, the Wedding of Alexander and Rossane for De Fabris. The themes for the two vases had been chosen by Canova: Zandomeneghi was to be inspired by the wall painting from the Roman era that was discovered in 1601 and was kept at the Villa Aldobrandini at the Quirinale, while De Fabris was to take on the theme of Girolamo Siciolante da Sermoneta’s fresco at the Villa Borghese (thought at the time to be the work of Raphael), and which in turn was related to the painting of the same subject that the Greek painter Aezione had made in the fourth century B.C., about which we have information because Lucian of Samosata mentions it in his Dialogues. These sculptures were later joined by anAltar with Bacchae sculpted by Bosa and anAltar with Fauns by Ferrari.

If everything had gone smoothly for the paintings (only De Min had a few too many setbacks due to the fact that he was more comfortable with fresco painting than oil painting), the same could not be said for the sculptures, which experienced several hiccups. The first problem was the bereavement that struck the group: Angelo Pizzi in fact did not make it in time to finish his work before his death, and the search for a replacement, which, as mentioned, was later identified in Bartolomeo Ferrari, could not help but result in slow progress of the work. It must then be added that Ferrari was faced with a work carved in low-quality marble, a detail that made the continuation of the sculptural group left unfinished by Pizzi somewhat difficult. There were also problems for Rinaldi, the very youngest sculptor, the one Cicognara had been thinking of from the beginning: he was struck down by an unspecified illness that weakened him a great deal, so much so that, despite the present and constant help of Canova (Rinaldi was one of his best pupils), even his work proceeded slowly and, once finished, was not of the quality the president had hoped for. Rinaldi therefore set to work again, but was only able to deliver the second version of his Chiron in 1821. However, even this work did not leave for Vienna, and a new sculpture on the same subject was assigned to Ferrari, but he did not manage to complete it until 1826. There were also problems with the vases, but their creators still managed to deliver them by the deadline of spring 1818: by that date, all the works had to be ready to leave for Vienna. And in the end the feat was almost entirely successful, because only Pizzi and Rinaldi’s sculptures were missing from the roll call.

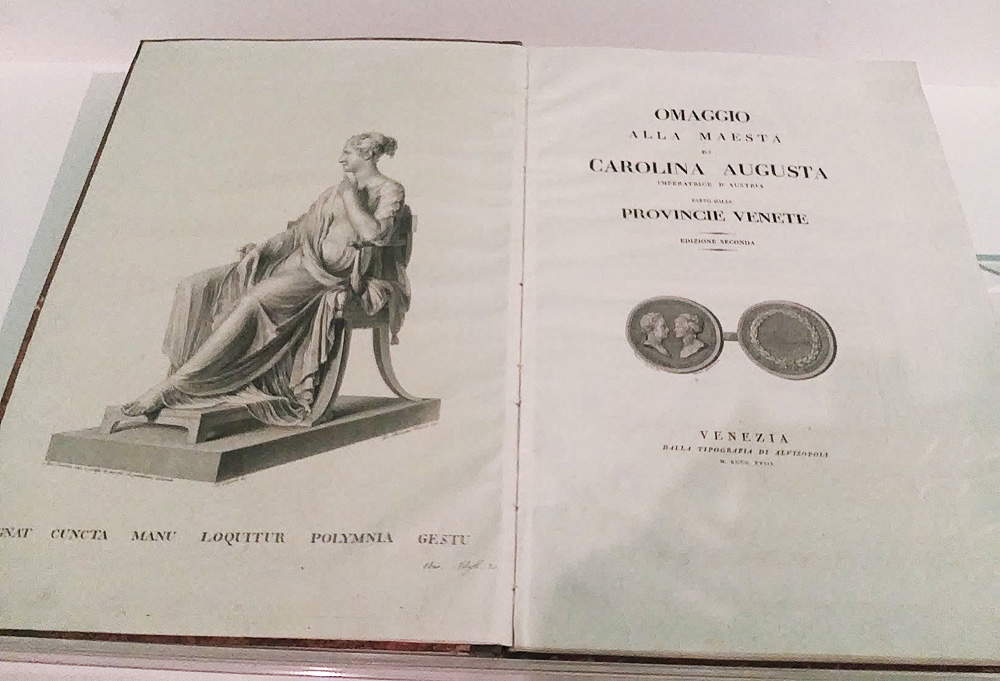

Cicognara then wanted the Homage of the Venetian Provinces to be celebrated in the most fitting manner: a commemorative medal with portraits of the newlyweds, designed by Angelo Pizzi, was minted (this is one of the highest examples of eighteenth-century Venetian medallistics), and the works were reproduced by means of engravings, provided with descriptions drawn up by literati, and collected in a volume that was printed in a couple of special copies decorated with medallions, and in a further precious copy, decorated with reproductions of reliefs by Canova, which was given to Carolina Carlotta Augusta.

|

| Bartolomeo Ferrari, Chiron instructs Achilles in music (after 1826; marble; Artstetten, Castle Collection). Work photographed at the Canova, Hayez, Cicognara exhibition (credit Finestre sull’Arte) |

|

| Angelo Pizzi and Bartolomeo Ferrari, Oath of Hannibal (1818-1821; marble; Artstetten, Castle Collection). Work photographed at the Canova, Hayez, Cicognara exhibition (credit Finestre sull’Arte) |

|

| Rinaldo Rinaldi, Chiron instructs Achilles in music (1821; marble; Venice, Gallerie dellAccademia, on deposit at the Polo Museale del Veneto Galleria Giorgio Franchetti at Ca dOro). Ph. Credit Galleria Giorgio Franchetti at the Ca’ d’oro |

|

| Giuseppe De Fabris, Vase with the Wedding of Alexander and Roxane (1817; marble; Vienna, Hofmobiliendepot, Möbel Museum). Work photographed at the Canova, Hayez, Cicognara exhibition (credit Finestre sull’Arte) |

|

| Luigi Zandomeneghi, Vaso con le nozze Aldobrandini (1817; marble; Vienna, Hofmobiliendepot, Möbel Museum). Work photographed at the Canova, Hayez, Cicognara exhibition (credit Finestre sull’Arte) |

|

| Bartolomeo Ferrari, Altar with Fauns (1818; marble; Vaduz-Vienna, Liechtenstein. The Princely Collections) |

|

| Homage of the Venetian Provinces to the Majesty of Carolina Augusta Empress of Austria made by the Venetian Provinces. Second edition (1818; Venice, Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia, Correr Museum Library) |

|

| Angelo Pizzi, Luigi Ferrari, Medal for the Wedding of Francis I and Caroline (1816; silver-plated bronze; Venice, Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia, Museo Correr) |

|

| The room of the Canova, Hayez, Cicognara exhibition dedicated to the homage of the Venetian provinces. |

Before leaving, the works also had to undergo the scrutiny of the very strict Austrian police, who had to check that there were no elements liable to censorship. The paintings, sculptures but also the sonnets with which the men of letters had wished to celebrate the enterprise were therefore scrutinized, and there were also some lyrics that did not pass the censorship’s meshes. These included a sonnet by Melchiorre Missirini (Forli, 1773 - Florence, 1849), who was guilty of celebrating the ancient Venetian Republic in his poems. And many of the descriptions of the works had to undergo changes as well: in particular, the illustrations of three of the four paintings with biblical subjects were rejected, since the censors frowned upon suggesting rules of moral conduct to sovereigns, and Cicognara was therefore required to illustrate the works with texts that had to do exclusively with art. And even for the painting with the Veduta della riva degli Schiavoni as far as the Giardini Reali, the censors had something to complain about: “ella forse converrà meco,” the Austrian governor of Venice, Peter Goëss, wrote to Cicognara, “in the appropriateness of inserting some brief mention of the emperor’s presence.” In practice, the Austrians had clearly instructed Cicognara and colleagues to describe only the subjects of the works. Thus, to comment on the matter, the great writer Pietro Giordani (Piacenza, 1774 - Parma, 1848) sent a letter on December 20, 1817, to his colleague Gaetano Dodici, in which, with boundless and bitter irony, he suggested, “Let us therefore rejoice that great rest is given and commanded to the intellects of our age. Napoleon, who was more valiant, made the pnesiers pay duty by stamping every sheet of books. These more tame ones exempt us from thinking and paying.”

All the works that were ready in the spring of 1818 were exhibited from May 24 to July 5 at the Chapter House of the former School of Mercy. The exhibition was a great success from the first days, and Cicognara was so enthusiastic about it that he wrote to Canova on May 28 that “the exhibition of the works makes a great sensation, and everything exceeds all expectations. Li historical paintings are beautiful, Hayez has made himself amirare above all and at some distance also comes De Min with a reasonable and well painted composition. Lattanzio supported himself with some good tabards and well colored very much, and Cozza with a wise composition. But Hayez’s triumph is full marks, and justly deserved. The perspective paintings are beautiful, and of a very varied style among them. They are four works for the Royal Cabinet. Li two vases are objects of wonder and delight, and poor Zandomeneghi yields in nothing to the sublime opra of Fabbris, which if it does not overcome him in beauty, perhaps surpasses him in accuracy. The ares are a marvel of beautiful execution, and starting from a beautiful type we have gone safe, and all the objects correspond and compete nobly with each other.” The artists involved in the undertaking were then all awarded a silver medal. After the exhibition, on July 13, the works, nineteen in all, left for Vienna, personally accompanied by the president of the Academy: first displayed in the Imperial Palace, they were then placed in the sovereigns’ apartments. The reception, however, was disappointing for Cicognara: the only one to show recognition was Carlotta Carolina Augusta, who donated a gold medal for each artist, and for the president a box of brilliants. And on his return, Cicognara sent deeply embittered words to Canova: “of Vienna I was satiated and nauseated; misery of ideas, poverty of taste, no courage for a noble and generous undertaking, ignorance much, presumption infinite: there is no good but the Empress.”

Of the works sent to Austria, there are only three that remain at the Imperial Palace in Vienna, namely Canova’s Musa Polymnia and the two vases. Almost all the other works are still in Austria, but in different locations, because they have undergone several changes of ownership over the years. Outside Austria are found only the Rinaldi group (the one that never left for Vienna: today it can be admired at the Giorgio Franchetti Gallery at Ca’ d’Oro, on deposit from the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice, which holds the ownership) and the De Min painting, which is perhaps now in the United States. Only two works, however, have not been traced: these are Liberale Cozza’s Return of Ahasuerus and Giuseppe Borsato’s Oath. Almost all of them, however, were able to make a temporary return to Venice, as mentioned above, for the major exhibition celebrating the bicentennial of the Gallerie dell’Accademia. A precious occasion, born from the passionate work of Roberto De Feo, lasting many years and still to be finished (after all, there are still two works to be found... !) to remember and make known one of the most intense pages of Italian art history.

Reference bibliography

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.