When the San Rossore Park in Pisa was full of dromedaries.

In Gabriele d’Annunzio’sAlcyone , the dromedaries of San Rossore Park become, more simply, the “camels.” An unusual presence in the Tuscan landscape, a gift from ancient times, animals that once populated the pine forests between Pisa and the sea. “They pass through the scrub, / they go toward the ripa, // among the piles of timber, / among the heaps of stipa, / the gibbuti camelli, / laden with faggots / of twigs and litter, / so grave and sad and dumb! / Under their distorted feet / creak the pine / arid, dead needles.” D’Annunzio imagined them like this, far from their homelands, passing sadly under the pines of San Rossore, along the scrub that divides the city from the sea, led by the “Tuscan hillbilly” with “the ancient / voice that his fathers / used for the furrow / to incite the good / late in toil,” animals “exiled, oppressed and afflicted.” Perhaps he had seen them in their lands, in the desert of Algeria, the noble Francesco Lanfreducci, long a prisoner of the Saracens, forced to work at the millstone, hearing the cries of camels being beaten, D’Annunzio thought: then, back in Pisa, to recall his experience and remark on how precarious existence is, he would have the enterprise “Alla Giornata” written on the lintel of his palace, which became so well known that it later came to signify the name of the elegant building overlooking the Lungarno.

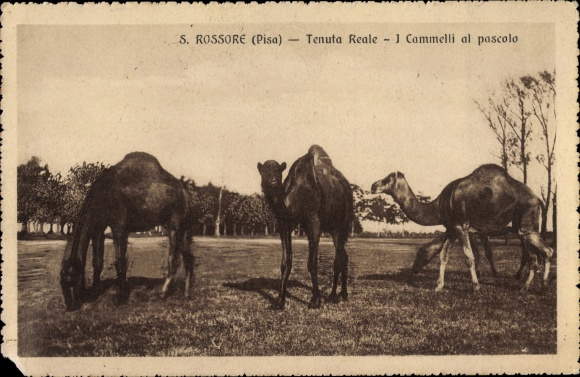

Dating back to those times is the arrival of dromedaries in Pisa, although they have nothing to do with the legend of Cavalier Lanfreducci. The first dromedary is attested in San Rossore in 1622, when it arrived, accompanied by a slave, as a probable gift to the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Ferdinand II de’ Medici, from the bey of Tunis. This is at least according to the historical reconstructions, still held to this day, that a nineteenth-century Tuscan veterinarian, Luigi Lombardini, published in one of his 1881 books, Sui camelli, entirely devoted to these animals: it will be worth noting that, at that time, “camels” were both dromedaries and camels proper, those with two humps (to distinguish them, dromedaries were called by the current term, or also “one-humped camels”). According to Lombardini, initially the first dromedaries were to be found on the Medici farm of Panna, near Scarperia, in Mugello, and a new contingent of these animals would arrive in 1663 after the Battle of Vienna, fought between the forces of the Holy League and the Ottoman Empire, with the victory of the Christians: they would be preyed upon by the Turks by a Tuscan general, a certain Arrighetti, who would make a new gift of them to the grand duke. By the end of the seventeenth century, some fifteen dromedaries were counted between the Panna farm and the San Rossore estate, and at the time they were kept “as curious objects of simple luxury,” Lombardini writes. Their numbers increased further in the eighteenth century, and with the rise of the Lorraines to the grand ducal throne, it seems that the idea had matured to put the “camels” to practical use: the population was therefore suitably refreshed with new specimens brought in from Tunisia, so that towards the end of the eighteenth century there were nearly two hundred dromedaries being used as beasts of burden and pack-animals. Towards the beginning of the nineteenth century the number decreased, due to some diseases that affected the herd, and throughout the nineteenth century a hundred dromedaries lived in San Rossore: some worked, others continued to be shown as curiosities, others were given as gifts, they were exploited for the hair that made stuffing for mattresses, the females were destined for reproduction, and some even ended up being slaughtered.

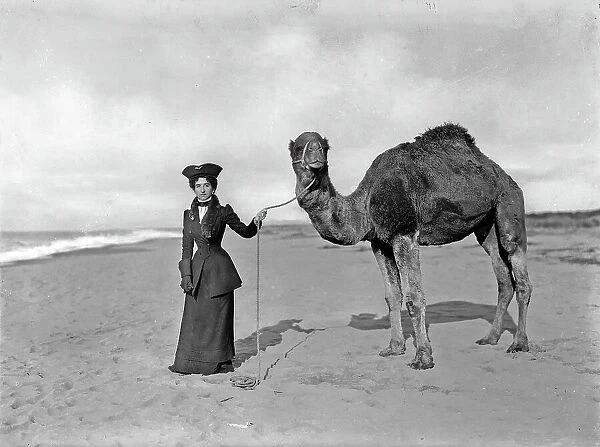

Dromedaries, for the Pisans, had become a familiar presence. They had adapted to the climate of the park. Of course, it was not that of the desert of Tunisia, every now and then they had to suffer a bit of cold, but after all, the dromedaries were not supposed to be so bad in San Rossore. They were beasts exploited for their usefulness, but they were also an attraction. “In a forest near Pisa I saw first two and then five camels,” has Friedrich Nietzsche tell the wayfarer in Human, Too Human. Some period photos depict ladies of the Savoy court, after the unification of Italy, walking on dromedaries in San Rossore Park. Even the ill-fated emperor of Mexico, Maximilian of Habsburg, confessed in his memoirs that he had wanted to see the dromedaries before anything else as soon as he arrived in Pisa: “On a large meadow, at the edge of a forest, we saw for the first time, with enthusiasm, those sand walkers going to work.”

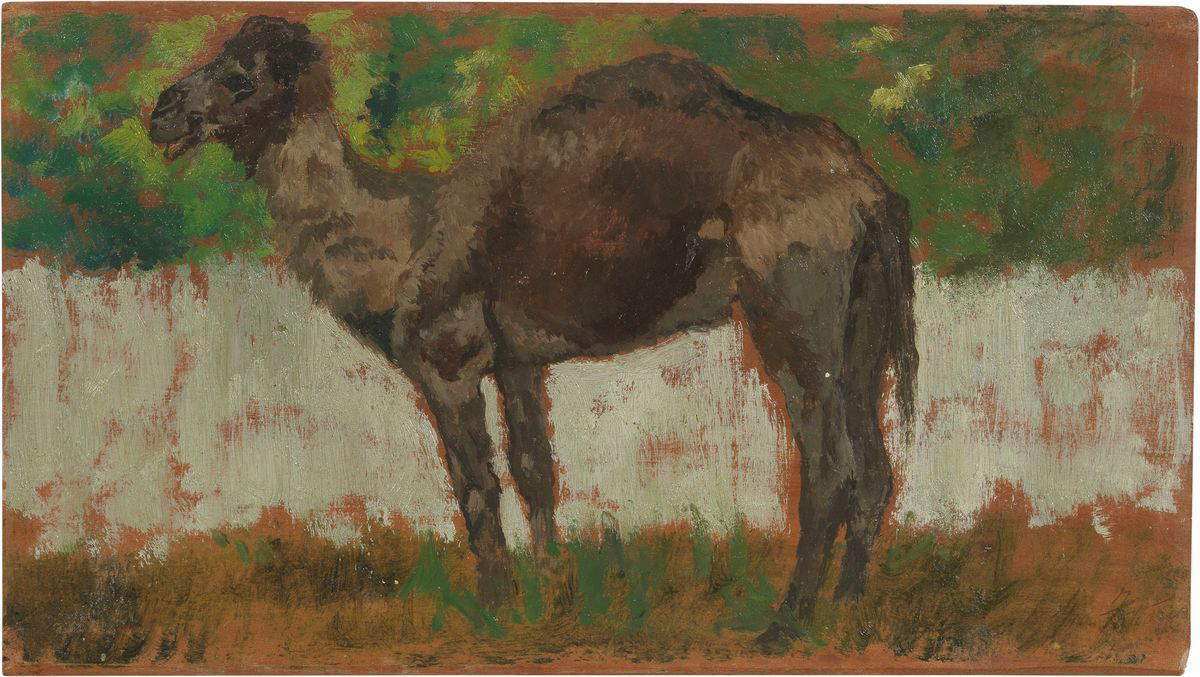

Of course, the dromedaries of San Rossore could not fail to fascinate the artists who frequented Pisa and its surroundings. Beginning with the most famous painter to have returned to us an image of a dromedary: Giovanni Fattori (Livorno, 1825 - Florence, 1908), the great Macchiaioli who painted a dromedary in one of his tablets, now preserved in a private collection, which is among the works bequeathed to his pupil Giovanni Malesci (it would later be published in the 1961 general catalog compiled by Malesci himself). Passed at auction in 2022 by Farsetti, in the catalog of that sale the Dromedary was described as a “unicum” by Leonardo Ghiglia, who compiled its file: “a surprising presence, exotic and apparently very distant from the world of popular and peasant elegy dear to the great Leghorn painter.” Fattori had seen the camels at San Rossore, a place he frequented, and here he painted his portrait of the animal, similar to his other works, such as the better-known horse in the Fattori Museum in Leghorn, with which the dromedary seems to share technique and period: “Fattori,” Ghiglia writes, “as is his custom, does not indulge in facile mannered exoticism, but sidesteps the danger of anecdote and postcard orientalism by inserting the synthetic volume of theanimal in a geometric grid of horizontal planes, defined through a play of calibrated light and tonal relationships that recalls the formal essentiality of the tablets of the early 1970s.” The mass of the animal, built up with broad, dense brushstrokes, enclosed by a synthetic drawing made evident by the outline, stands out against an undefined background, as is often the case in these tablets with a sketchy flavor, executed in rapid, perhaps directly on the spot, to preserve an impression of a subject, a motif, an inspiration, and which constitute one of the most interesting and lively souls in Fattori’s repertoire.

More thoughtful, however, is an oil on panel by the Hungarian Károly Markó the Elder (Levoča, 1793 - Florence, 1860), one of the best and oldest paintings depicting dromedaries in San Rossore: Markó, in 1832, had moved to Italy and would never leave it again. Settling in Tuscany, he often frequented Pisa and its coastline, and his painting now in the National Gallery of Slovakia in Bratislava, known as Camels in a Southern Landscape, should perhaps be better circumscribed and given a different title (perhaps a more appropriate Camels in San Rossore), since the artist could only see “camels” among the pine trees on the outskirts of Pisa. And what is seen in the painting is the landscape of the Pisan coastline, with the pines in the distance, the beach on which abound what appear to be helichrysum flowers, typical of the scrubland of these lands, and three dromedaries on the beach, one lying down, in an almost contemplative attitude, since he is caught looking at the sea, and two depicted turning their eyes to the pine forest. A traditional, academically-minded landscape painter, still bound to a late neoclassicism, yet capable of painting very fine works, able to meet the taste of the upper-class patrons of the mid-nineteenth century, Markó paints on his panel a tasty scene, imagined to intrigue, focused precisely on the animals, which take over from everything else, a case, moreover, not so frequent in his painting: Markó used to focus on the glimpses, views, and nature, rather than on the figures that populated his landscapes.

Also fascinated by dromedaries was Odoardo Borrani (Pisa, 1833 - Florence, 1905), among the few Macchiaioli who frequented the San Rossore park. The Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea in Rome has one of his works, Cammelli nella tenuta reale di San Rossore, of which there is also a version preserved today in a private Florentine collection, which was exhibited in 1883 at the Società d’Incoraggiamento delle Belle Arti in Florence. Borrani produced twenty-seven pencil drawings of views of San Rossore during that period, and the painting is a kind of synthesis of this graphic activity: a scene of daily work on the estate, with three dromedaries advancing laden with their chariots, the countrywomen approaching perhaps to observe the goods they carry, the farmer sitting on the hump of the first dromedary caught leading the small caravan, chickens scratching on the rena, pumpkins thrown on the ground, a red cart (a typical presence in theart of the Macchiaioli) pulled by a pair of Maremma oxen, further back some haystacks covering the horizon line, and in the background the green outline of the pine forest. The episode Borrani restores to the viewer’s eyes has no hint of exoticism, despite the presence of the unusual animal: it is nothing more than a country scene, a scene that must have been familiar to him as to all those who lived in the Pisa of the time, so much so that the painter’s interest is directed primarily toward rendering the effects of light, theclear and terse atmosphere of the Pisan shoreline, the colors of the sky that occupies half of the composition, and offers a clear indication of what elements most captured the attention of the artist, one of the most talented of the Macchiaioli group.

There is also no shortage of engravings depicting dromedaries: the curious fact is that these animals often appear in front of the monuments of Piazza dei Miracoli, as if they were perceived as symbols of the city, on a par with the Duomo, or the Leaning Tower. Tradition, after all, has it that these beasts were called “leaning camels.” Here they are then, in the distance, just in the direction of the tower, in an engraving of 1851, attributed to the draughtsman Ranieri Grassi and now preserved in the National Museum of the Royal Palace in Pisa: there are three of them, and they are still led by a peasant, at the edge of a Piazza dei Miracoli that appears to us exactly as it is today, with the lawn on which the four monuments stand out and people strolling on its edge.

Dromedaries were so closely associated with Pisa that they even ended up on the cover of a book published in 1834: a Raccolta di XII vedute della città di Pisa, by Bartolomeo Polloni, an engraver and draughtsman who also took care of illustrating his plates. Here, animals appear in the foreground, immersed in their pine forest, with the outline of the city, the Baptistery and the tower looming in the distance. They are there, on the banks of the Arno, attentive and peaceful, almost guarding the city.

And then, what happened? The war came, World War II, and the dromedaries, already decimated and reduced to a few, almost all died during the conflict, culled and reduced to meat to feed German troops. A few survived, but they were few in number. The last dromedary, Nadir, departed in the 1960s, and today the skeleton of that last descendant of the camelids who arrived in Pisa from the desert in the 17th century is preserved at the Museum of Natural History in the Certosa di Calci. Then, in the years that followed, there were some attempts to reintroduce dromedaries to San Rossore, but these were not followed up.

It was only recently, in 2014, that the dromedaries returned to San Rossore: a donation from the AGESCI allowed three splendid specimens, one male and two females, to restore that presence that was so dear and familiar to the Pisans of old. They have since returned. The entity that manages the San Rossore estate believes they are an important presence to enhance the park. These dromedaries, like their fellows who inhabited the park centuries ago, are also employed to work: they periodically participate in cleaning the beach of San Rossore and its dunes. And each time this operation becomes a kind of celebration, which is promoted and properly communicated. One can participate as a volunteer and clean the beach together with the dromedaries. And then they, from time to time, come out of their stables, on the grounds of the San Rossore Park agro-livestock farm, and show up when there is some special event. The opening of a race at the racetrack, for example. Or an environmental education day. Of course, they are probably better off than their ancestors: they have to slog less, but still, even they are asked to work. Most importantly, they are back to being a welcome presence. A presence that makes unique the wonderful park that, for four centuries, has been their home. I wonder if they will feel nostalgia for their wilderness.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.