When Telemaco Signorini painted and denounced the drudgery of the Arno risers.

In 1874, when the great Macchiaioli artist Telemaco Signorini (Florence, 1835 - 1901) exhibited his towpath, one of the most celebrated products of his brush, for the third time exactly ten years after its creation, the reception it received was not the most benevolent. In particular, his painting was panned by a terribly negative review, published in the columns of La Stampa and signed by Guglielmo Stella (Milan, 1828 - Venice, 1894): after all, it could not have been otherwise, since Stella did not look favorably on the school of the Macchiaioli, for several reasons, both stylistic (the Macchiaioli were seen somewhat as the corrupters of the realist school) and content-related (Signorini often dealt with themes of social denunciation, as inAlzaia, and this was particularly risky ground). The Florentine painter had shown the painting for the first time the same year it was made, in 1864 at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Florence, then took it, in 1873, to the Universal Exhibition in Vienna, where it was, moreover, awarded a prize, and he showed it again in 1874, again in Florence, at the exhibition of the Florentine Promoting Society: in fact, the artist believed that the time was ripe for wider appreciation. He was wrong: the exceptional scope of the painting, one of the most modern and innovative of that season, quite clearly troubled Guglielmo Stella’s soul. And his demolition of thetowpath was total.

The first considerations concerned the style of Signorini’s work. “The picture he exhibited,” Stella wrote, “wonderfully sums up his system. The subject sometimes null, often sad and desolating; the grace of the lines, the sympathy of the whole, the careful study of form and design, things of no importance; the coloring very little care; one thing accurate; one thought dominant, the novelty of the general impression and the value of the different tones obtained, of the rest nothing. And if the public does not like them so much the better: what do those poor boors know? Art is all made for the adepts who made the palate for the gray and indefinite paintings that would have pretended to represent the modern resurgence.” As for the scene depicted and its symbolic value, the Venetian painter asserted that “it produces a most distressing impression and by the subject and the manner of expressing it, but from the philosophical side it aspires to a certain elevation and achieves it from a certain point of view, but in our opinion art lends itself very poorly to certain philosophical-humanitarian demonstrations, art has for its mission to cheer, to soften and to produce agreeable impressions.” Signorini’s reaction, however, was not long in coming, and the artist responded by publishing an article in the Venetian newspaper Il Rinnovamento. With great sarcasm, he implied that Stella should have appreciated his work, since the Venetian artist was going on to argue that a good painter should sincerely refer to nature: Signorini, too, had looked to nature, and this was, moreover, the only characteristic he had in common with that Gustave Courbet (Ornans, 1819 La Tour-de-Peilz, 1877) to whom Stella had compared him (Signorini wrote that Stella did not know Courbet’s art, or, if he did, he did not understand it at all).

|

| Telemaco Signorini, The towpath (1864; oil on canvas, 54 x 173.2 cm; Private collection) |

It should be pointed out, however, that there was another analogy with Gustave Courbet’s art: the character of social criticism that Thetowpath necessarily assumed. The painting is set in Tuscany, on the banks of the Arno near the Cascine Park on the outskirts of Florence. Describing the subject is Signorini himself, in a letter sent in 1892 to the president of the Accademia di Belle Arti in Florence (a piece of writing that is, moreover, extremely useful for reconstructing the artist’s entire biography up to that time): “in 1864 I did a painting of my greatest with many figures almost life-like pulling a boat against the current of the Arno, The towpath. Later in 1873, exhibited at the Vienna International Exhibition, it earned me a medal.” The painting’s protagonists are five tan-skinned characters, dressed in threadbare clothes, bent over with fatigue: they are five towpaths, ortowpath workers. This term designated the rope needed forhauling, the custom of dragging boats up the waters of a river on the shoulder from the shore: it happened when there was no favorable wind, or when the ship was not equipped with oars. There were special walkways on the banks of the river that had to guide the towpath workers, the “alatori” or, in Tuscan terms, the “alzaioli.” It was extremely strenuous work, bordering on inhuman, since the men called to practice it almost lost their dignity, becoming like pack animals, exhausted by their efforts. In this painting, art historian Rossella Campana has written, Signorini “chose as his central theme the world of labor in its most archaic form, the result, so to speak, of a biblical curse, in a context, that of Tuscany before the Unification of Italy, which was still governed by primordial laws: the latter had not yet been modified by the progress and mechanization of the industrial age.”

Commentators have noted how Signorini was deeply influenced by the writings of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (Besançon, 1809 - Paris, 1865): in his works, the French philosopher had spoken of social justice, equality, marginalization, and freedom. Writing to Vincenzo Cabianca in 1868, the artist is reported to have said, "I read Proudhon De la justice etc. I like it very much. I am often made to reflect on the wrong I had in not reading him before now it seems to me that if a man does not acquire the sense of righteousness after reading this author, it means that in himself there has never been even the germ of a gentleman." The work to which the artist refers is De la justice dans la révolution et dans l’église, but we know that as early as 1855 Signorini had begun reading Proudhon, and his desire to propose art that was also denunciatory was itself a reflection of such readings: Proudhon had also written a short pamphlet titled Du principe de lart et de sa destination sociale, published posthumously in 1865, in which the author posed the problem of the social role of art, asserting that the purpose of art should beutility (underlying the treatise was the idea of “reconciling art with the just and the useful”), and that in order to achieve this goal, content should prevail over form, since art, according to its own definition, is but an “idealistic representation of nature and ourselves, with a view to the physical and moral perfection of our species.”

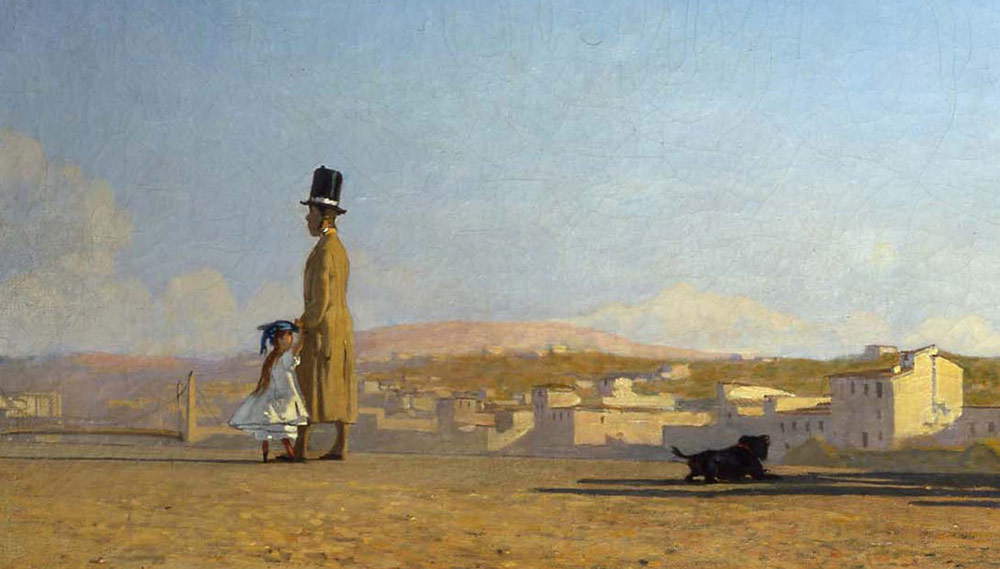

In order to make his denunciation even stronger, Signorini included a decidedly strong detail in the painting: in the background we see, in fact, a bourgeois fully dressed, walking along holding the hand of a little girl, in the company of a lingering dog, who remains between the two and the lifters. The figures of these two characters, silhouetted against the verdant landscape, with the sun illuminating the first buildings of Florence, help to accentuate this contrast that is a symptom of obvious social injustice: they are not in the least affected by what is happening behind them; on the contrary, they turn away indifferently. The light itself is a further element of denunciation: it is a terse light, which in accordance with Macchiaioli poetics creates strong contrasts between light and shadow, and which here gives rise to backlighting effects that throw the tried faces of the lifters into darkness: it is a highly symbolic device, since with the light that does not help us to distinguish their faces it is as if their personalities are cancelled out, oppressed and destroyed by that strenuous work. Note then the hand gestures of the last two: one, wracked with fatigue, wipes off his sweat but almost seems to rest his face on his disconsolate back, while the other tries to brush against the rope to help himself. Signorini’s five risers are a monument to fatigue. “They seem photographed from life,” reads an 1873 review.

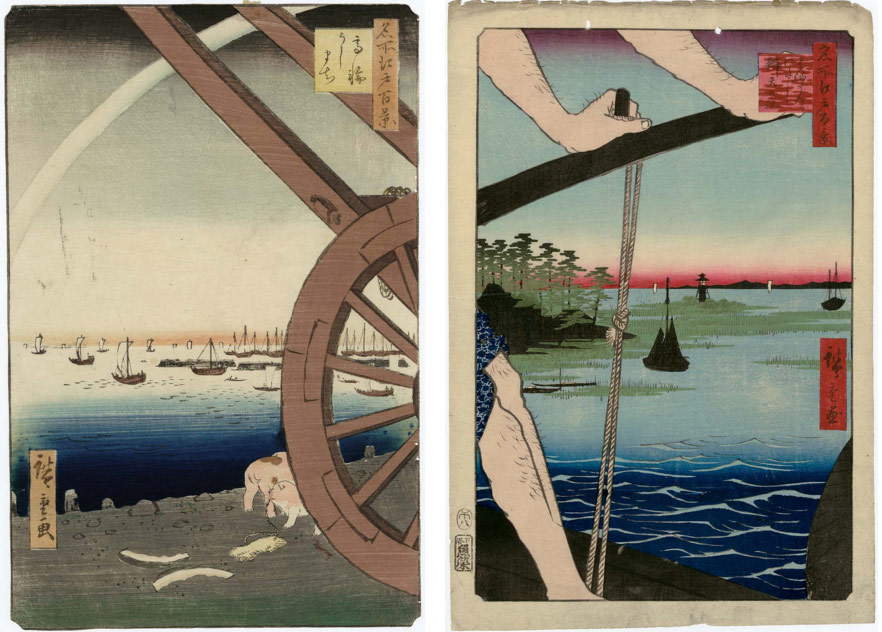

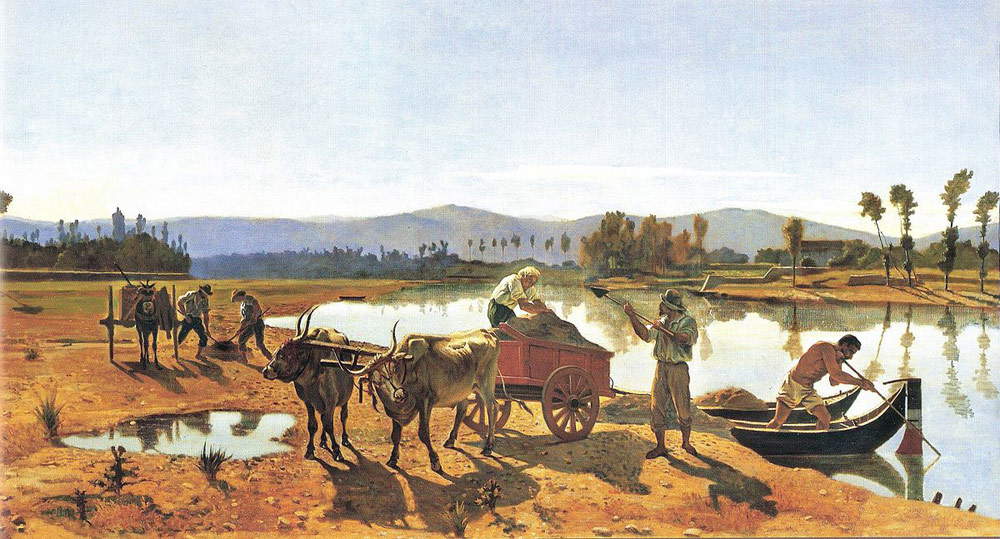

Art historian Vincenzo Farinella has pointed out how Signorini may have been inspired by theJapanese art of Utagawa Hiroshige (Edo, 1797 1858) to create his towpath, bolstered in part by a stay in Paris in 1861 (the fashion for Japonisme had already spread to the French capital). “An image so surprising, so risky from the compositional and chromatic point of view,” the scholar wrote, “can only be explained by assuming that Japanese prints had fallen into Signorini’s hands.” And this is not only because of certain solutions such as the sharp contrasts that make us think of the two-dimensionality of Japanese works, or the extreme synthesis, which is also shared with Japanese prints. The similarity is closer. The idea of the sharply lowered point of view may come from knowledge of a print by Hiroshige, known as Takanawa Ushimachi (“View of Ushimachi in Takanawa Prefecture”), where the viewer is imagined so far down that the horizon, as in thetowpath, ends up very close to the lower edge of the composition. The same is true of Haneda no watashi Benten no yashiro (“Haneda Ferry and Benten Shrine”) where similar are the details on the riverbank, and even the tightrope motif seems almost to have a direct derivation. And again, another source for Signorini could be a slightly earlier painting, the Renaioli dell’Arno by Stanislao Pointeau (Florence, 1833 - Pisa, 1907), another Macchiaiolo who set his composition in a sunny countryside struck by a warm and violent light, such that it again creates marked contrasts on the terrain from the river landscape and on the waters of the Arno itself.

|

| Telemaco Signorini, The towpath, Detail of the towpaths |

|

| Telemaco Signorini, The towpath, Detail of the burghers |

|

| Left: Utagawa Hiroshige, Takanawa Ushimachi (1857; ukiyo-e ink and color print on paper, 34.1 x 22.5 cm; Boston, Museum of Fine Arts). Right: Utagawa Hiroshige, Haneda no watashi Benten no yashiro (1857; ukiyo-e ink and color print on paper, 36.8 x 25.2 cm; Boston, Museum of Fine Arts) |

|

| Stanislao Pointeau, Renaioli dell’Arno (1861; oil on canvas, 100 x 189 cm; Private collection) |

Telemaco Signorini’s painting is held in a private collection (it went to auction in 2003 at Sotheby’s for nearly three million pounds), but a photographic reproduction can be found at the Museum of Boating and Rowing in Limite sull’Arno. In fact, many of the hoists (the “damned of the river,” as they are described in the museum’s panels) came from this village on the banks of the Arno, which lies just beyond Empoli and was once one of Italy’s most important centers of shipbuilding: only a few shipyards survive today, and they are mainly active in pleasure boating, but when Telemaco Signorini was painting his works, ship production in Limite sull’Arno, Tuscany, was second only to that of Viareggio and was more abundant than that of Livorno and Porto Santo Stefano. Production was favored by the presence of lush forests that covered the Montalbano area, the border zone between the Arno valley and the Pistoia hills. This was an almost inexhaustible source of timber, particularly suitable for ship carpentry: whole families of woodcutters rented portions of the forest and obtained from it the construction timber that they would then put on the market to meet the needs of the shipwrights, that is, the highly skilled workers who were able to process the material in such a way as to make it suitable for boat building (the Limone shipwrights were famous throughout Italy for their great skill). In the period of maximum production intensity, brigantines whose capacity exceeded two hundred tons also came out of the Limone shipyards.

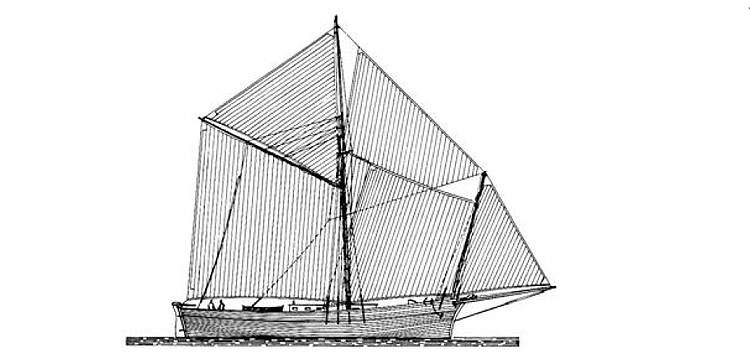

It was the navicelli, however, that were the boats peculiar to Limite sull’Arno, as well as the type most frequently produced by the local shipyards, so much so that a square in Limite, Piazza dei Navicellai, is now dedicated to the workers employed in the construction and transportation of navicelli. These were boats suitable for river navigation: at one time the Arno was navigable and was the preferred transport channel for building materials and foodstuffs, which, following the course of the river, arrived easily and quickly from the coast to Florence or vice versa (only the advent of railways in the mid-19th century would mark the beginning of the decline of river transport). The navicello, in particular, had been built since before the seventeenth century. It had a capacity ranging from thirty to seventy tons, was equipped with two masts, the first of which sloped toward the bow, as well as two main sails: the work of the hoists was often necessary to transport them, and under certain conditions (i.e., when it was necessary for the boat to go upriver against the current) it became the only way to drag the navicelli over the waters of the Arno. All the stages of construction, the tools needed, the materials used, and the efforts of those who worked on the production and transport of the boats (shipwrights, sawyers, caulkers, scafaioli, and the alzaioli themselves) are an integral part of the itinerary of the Limite sull’Arno Shipbuilding Museum. A museum where it is possible to hear these stories of work and toil from those who have always lived in the shipyards. Limite’s is a community that knows the value of sacrifice, strongly rooted in its traditions and its territory.

|

| A room at the Limite sull’Arno Shipbuilding and Rowing Museum. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Model ships at the Museum of Shipbuilding and Rowing in Limite sull’Arno. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Drawing of a navicello |

|

| Limite sull’Arno. Ph. Credit Finestre sull’Arte |

|

| Telemaco Signorini, Limite sull’Arno (c. 1890; oil on cardboard, 40 x 50 cm; Viareggio, Matteucci Institute) |

And it was precisely the village of Limite that later became the subject of a painting that Telemaco Signorini himself executed around 1890. In the center, the Arno River flowing through the countryside and reflecting the clouds in the sky. On the left, the houses of Limite sull’Arno overlooking the banks and in turn reflected in the water. On the opposite bank, the shrubs and trees of riverine vegetation. Farther back, the hills of Montalbano, those that provided timber for the boats. It looks like a totally different painting than thetowpath: here all narrative intent is lost, and on the contrary the village is fixed in a timeless dimension, placid and poetic, caught in a precise moment, with that vibrant brushstroke that was typical of the Impressionists. In fact, a new season had opened in Telemaco Signorini’s career: in fact, the artist had begun to break away from the "strong>macchia" to embrace a painting of a more international scope, attentive to the innovations that had come from France.

The work would later gain posthumous recognition: in 1928, in fact, it was exhibited at the Venice Biennale. The portrait of a village that still seems out of this world and out of time thus entered the most up-to-date of artistic contexts, and became almost a sort of counterbalance to thetowpath. Thetowpath, moreover, would have offered more than one cue to other artists: another painter of the time, Adolfo Tommasi (Livorno, 1851 - Florence, 1933), painted the towmen in a painting of a homologous subject, only in a larger format, and with a different point of view, since the painter had placed himself in front of the workers, so that the frame also included the boat dragged on their shoulders. This painting is also, moreover, reproduced in a photograph in the Museum of Shipbuilding and Rowing in Limite sull’Arno. It was, however, a work with a less innovative character: Tommasi seemed almost to want to emend it from the strong charge of social criticism that had instead distinguished Telemaco Signorini’s painting. Which remains one of the most political paintings of 19th-century Italy. Looking at it, one almost seems to hear the chirping of the cicadas, the rustling of the foliage as the wind passes, the earth stirred by the passage of the hoists, the sound of the water ploughed by the boat they are pulling, the subdued groans of their toil.

Reference bibliography

- Vincenzo Farinella and Francesco Morena (eds.), Japanism. Suggestions from the Far East from the Macchiaioli to the 1930s, exhibition catalog (Florence, Palazzo Pitti, April 3-July 1, 2012), Sillabe, 2012

- Giuliano Matteucci, Fernando Mazzocca, Carlo Sisi (eds.), Telemaco Signorini e la pittura in Europa, exhibition catalog (Padua, Palazzo Zabarella, from September 19, 2009 to January 31, 2010), Marsilio, 2009

- Lorella Giudici, Lettere dei macchiaioli, Abscondita, 2008

- Francesca Dini (ed.), Da Courbet a Fattori. I Principi del vero, exhibition catalog (Castiglioncello, Centro per l’arte Diego Martelli - Castello Pasquini, from July 16 to November 1, 2005), Skira, 2005

- Roberto Peruzzi (ed.), La terra e il fiume. Arti e mestieri a Limite sull’Arno, exhibition catalog (1987), Comune di Capraia e Limite, 1987

- Mila Busoni (ed.), Wood cycle and shipwrights. Carpenters and Naval Tradition in Limite sull’Arno, exhibition catalog (Limite sull’Arno, September 3 to 30, 1983 and Genoa, International Boat Show, October 15 to 24, 1983), Comune di Capraia e LImite, 1983

- Pier Carlo Masini, Heresies of the nineteenth century: to the secular, humanist and libertarian sources, Editoriale Nuova, 1978

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.