On October 30, 1567, a flood of the Brenta River destroyed the bridge that connected the center of Bassano to the district of Angarano: it was a very old bridge, first attested in 1209, and in any case built after 1157, according to what is known from documents. It was a covered wooden bridge, accessed by passing through a gate, and was an extremely important connecting structure for the city. It was not the first time that the waters of the Brenta destroyed it, so much so that in 1525, after yet another flood, the city government considered building a stone one, only to return, in 1530, to the usual wooden bridge. At times when the bridge was destroyed or impracticable, the connection between one bank of the river and the other was provided by a genuine ferry service that Bassano’s inhabitants would initiate while waiting for the city to restore the bridge’s functionality. After the flood of 1567, however, the city decided to entrust the reconstruction to one of the greatest architects of the time, namely Andrea Palladio (Andrea di Pietro della Gondola; Padua, 1508 - Maser, 1580), who was something of a Bassano regular. The affair was re-enacted and deepened by the exhibition Palladio, Bassano and the Bridge. Invention, History, Myth (at the Bassano del Grappa Civic Museums from May 23 to October 10, 2021), centered in part on the role the great Venetian architect played in the reconstruction of the bridge.

We know that Palladio had been in close contact, at least since 1548, with a local nobleman who had a home in Vicenza, Giacomo Angarano (exactly like the neighborhood joined to the center of Bassano), eighteen years younger than the architect, but his great friend despite the age difference. The relationship between the two was very close: Angarano advanced Palladio a sum of 60 scudi d’oro for his daughter Zenobia’s dowry (the marriage contract was signed in Palazzo Angarano itself), the architect paid homage to his friend in the Quattro Libri dell’Architettura, and again for Angarano Palladio worked on at least three projects, namely a palace, a villa, and a bridge. The palace was never built, while the villa (i.e., Villa Angarano Bianchi Michiel in Bassano) and the bridge (the bridge over the Cismon stream, which is about thirty kilometers north of Bassano: it stood on land belonging to the Angarano family, who had wanted to build it to speed up connections in the area and earn money by collecting a toll for crossing) were completed. Palladio was also known for his skill in solving hydraulic problems and, in his “resume,” he already boasted experience on bridges, both wooden and masonry, since at least 1544. And it was precisely as an expert on bridges that Palladio found himself a guest of Angarano in 1566, and it is likely that the city’s decision to entrust Palladio with the reconstruction of the bridge was also due to the noble friend’s intercession.

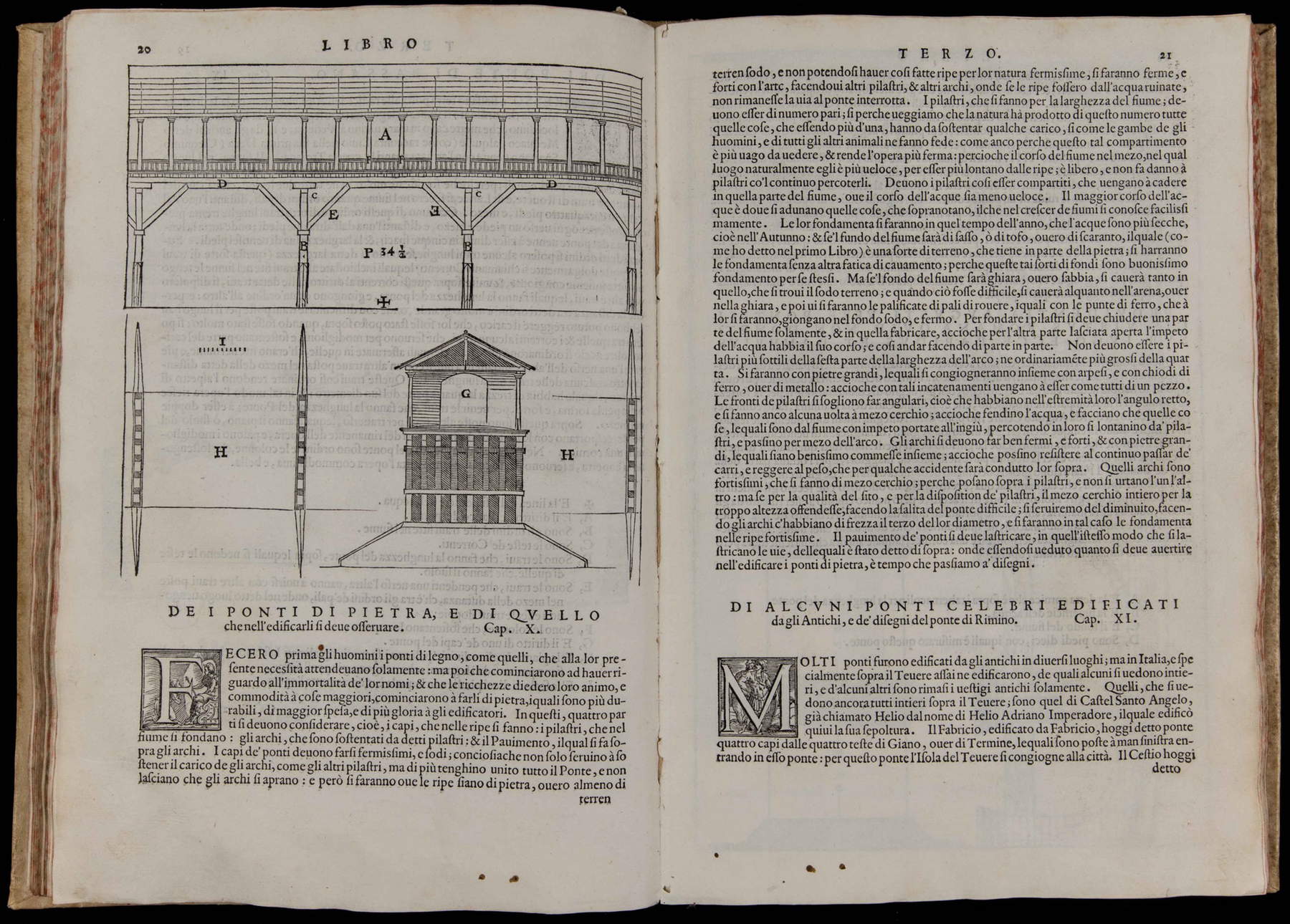

A payment dated January 1, 1568, made known in the 18th century by Tommaso Temanza, Palladio’s biographer, is preserved, for which 28 liras are paid to the architect for proposing a “dessegno del ponte, de mandato de li spectabili sindaci.” The history of the reconstructions of this structure, writes scholar Donata Battilotti in the catalog of the Bassano exhibition, “sees recurring debate about a rebuilding in masonry or wood, so Temanza’s lipothesis that this occurred this time as well and that Palladio first proposed a stone bridge, pushed and supported by a part of the local ruling class, seems reasonable.” Moreover, in the first of the Four Books, Palladio includes a design for a stone bridge without specifying the purpose but emphasizing that he was “sought after by some gentlemen” and making it clear to the reader that the work was not executed. That it may have been a design for the Bassano bridge is possible, however, by virtue of the fact that the measurements of the structure correspond to those of the Brenta River at the point of crossing, and “thus the choice of piers sturdier than dell’ordinario,” Battilotti explains, “fits well with the characteristics of the river, ’which is very fast,’ allowing resistance ’to the stones, and timbers, which are carried allingiù by it.’”

|

| Andrea Palladio, Plan, profile and cross section of the Bassano bridge, in I Quattro Libri dellArchitettura di Andrea Palladio, Venetia, Dominico de Franceschi (Venice, 1570; printed volume, 310 x 215 mm; Bassano del Grappa Biblioteca Civica, inv. II C 18). Volume that belonged to Antonio Canova |

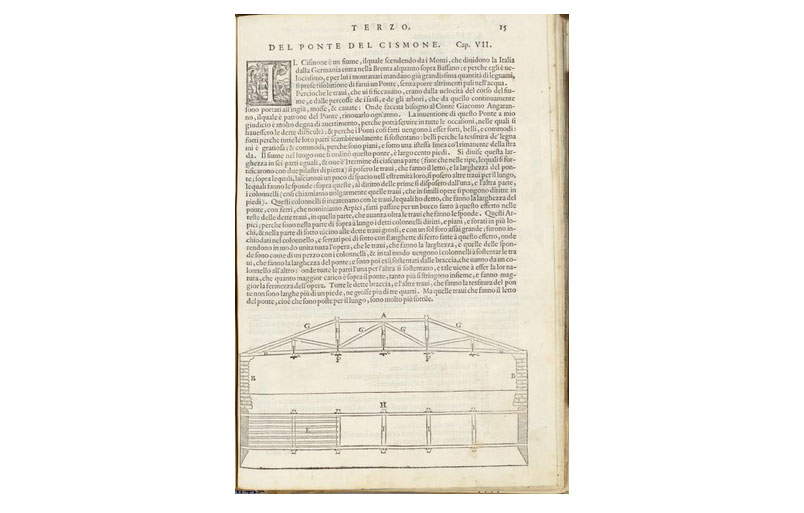

However, Palladio also had experience with wooden bridges, as attested precisely by the story of the bridge over the Cismon, which was already passable in 1552 (although it was later destroyed by a flood about fifty years later). For the stream (we do not know, however, the exact location), the architect designed a bridge characterized by a “limpid structural scheme,” wrote architect Mario Piana: “on the chain (composed of an unspecified number of beams, perhaps three, joined together by means of Jupiter’s dart brackets, as was the usual practice) mount five columns, three major central and two minor lateral. From the ends of the edging two sloping struts converge on the counterchain; six thunderbolts interposed alternately between the foot and top of the columns complete the triangular mesh.” The timbers of the deck were supported by “harps” (irons) that Palladio, in the project, describes as “made to pass through a hole made to this effect in the heads of the said beams, in that part which advances beyond the beams that make the banks.” It is, Piana explains, an “unprecedented constructive singularity,” designed to make all parts of the bridge support each other. The bridge over the Cismon represented one of the peaks of the architectural and engineering culture of the time and was also taken as a model in the following centuries.

The great architect is then known not only for the projects he actually carried out, but also for some grandiose ideas that unfortunately remained only on paper: the most famous of these is that for the Rialto Bridge in Venice, for which Palladio drew up two plans, one found on a sheet of paper preserved in the Civic Museum in Vicenza, and one published in the Quattro Libri. More than a bridge, however, says Guido Beltramini, curator of the Bassano Museums exhibition along with Barbara Guidi, Fabrizio Magani and Vincenzo Tiné, Palladio’s was a plan for a rearrangement of the entire Rialto area, one of the busiest areas of the city. From the material we have at our disposal, Beltramini writes, it is possible to assume “that Palladio’s design process began with an initial solution of a bridge with five arches, allowing a progressive and easier ascent,” and after reasoning “on the impossibility of realizing two head squares (unless a vast existing area was demolished) but not wanting to reduce the number of stores, Palladio thought of transferring them to the bridge itself, increasing its width, but keeping it with five arches.” This was the phase in which the artist studied variants for the bridge’s heads, for which two drawings remain that are also kept in the museums of Vicenza. However, the five-arch solution made boat traffic impossible, which is why Palladio drew up a new design, with three wider arches.

However, the idea was to create an innovative bridge-piazza, a kind of artificial island that could be frequented by the inhabitants. The project for Rialto dates, according to Beltramini, to the time of the meeting between Palladio and Giorgio Vasari (Arezzo, 1511 - Florence, 1574), which took place in the spring of 1566: according to the scholar, the two artists had the opportunity to discuss the project, probably starting from the description of a project for Rialto drawn up by Giovanni Giocondo (Verona, c. 1433 - Rome, 1515), which Vasari mentions in the Giuntina edition of the Lives, which the Arezzo historiographer is said to have published in 1568. According to Beltramini, the two may have discussed precisely Giovanni Giocondo’s project, and this discussion may have stimulated Palladio to try his hand at a personal design for the Rialto bridge. It was, however, a project that never saw the light of day, except in the splendid painting by Canaletto, preserved at the Pilotta in Parma, commissioned from him in the 18th century by Francesco Algarotti: a Venetian capriccio featuring the bridge envisioned by Palladio.

|

| Andrea Palladio, Progetto del Ponte sul Cismon in I Quattro Libri dellArchitettura di Andrea Palladio, Venetia, Dominico de Franceschi (Venice, 1570; printed volume; Vicenza, Palladio Museum). Work not in exhibition |

|

| Andrea Palladio, Rialto Bridge in Venice, elevation of elevation on the Grand Canal (1566; davorio point, pen and brown ink on paper, 477 x 752 mm; Vicenza, Museo Civico di Palazzo Chiericati, inv. D25 r) |

|

| Andrea Palladio, Rialto Bridge in Venice. Elevation of an Entrance Facade (1566; davorio point, pen and brown ink, highlights and dacquerello touches on paper, 500 x 425 mm; Vicenza, Museo Civico di Palazzo Chiericati, inv. D20r) |

|

| Antonio Canaletto, Capriccio con edifici palladiani (c. 1750; oil on canvas, 58 x 82 cm; Parma, Complesso monumentale della Pilotta, inv. 284) |

Returning to Bassano, as plausible as the hypothesis is that Palladio must have launched the idea of a stone bridge, a debate must nevertheless have arisen afterwards that gave rise to other proposals: “one of these,” Battilotti explains, “illustrated by an anonymous engineer to a rather skeptical city council, envisaged a bold wooden structure with a single span resting on four styles without being chained to them so that it too would not be swept away by the current in the event of a flood.” Eventually, on March 31, 1568, it was decided for the dov’era com’era: the city council decreed that “esso ponte sii reffatto et constructo nel modo et forma che era il precedente menato via dalla Brenta, cum quelle adiuncte che parerà alli protti et maistri che lo costruirano.” No novelty, then: the bridge would trace the previous one, probably because it was less expensive and because the construction technique was already widely tested. Palladio, therefore, complied with the decision and in July 1569 had a model of the bridge picked up in Vicenza, arriving after a year of work during which the city of Bassano had procured resources and lumber for the construction, for which the Vicenza carpenter Battista Marchesi, who had already worked in Vicenza on the Basilica and for the dome of the Duomo and whose name had been advocated for certain by Angarano and perhaps also by Palladio, was appointed superintendent.

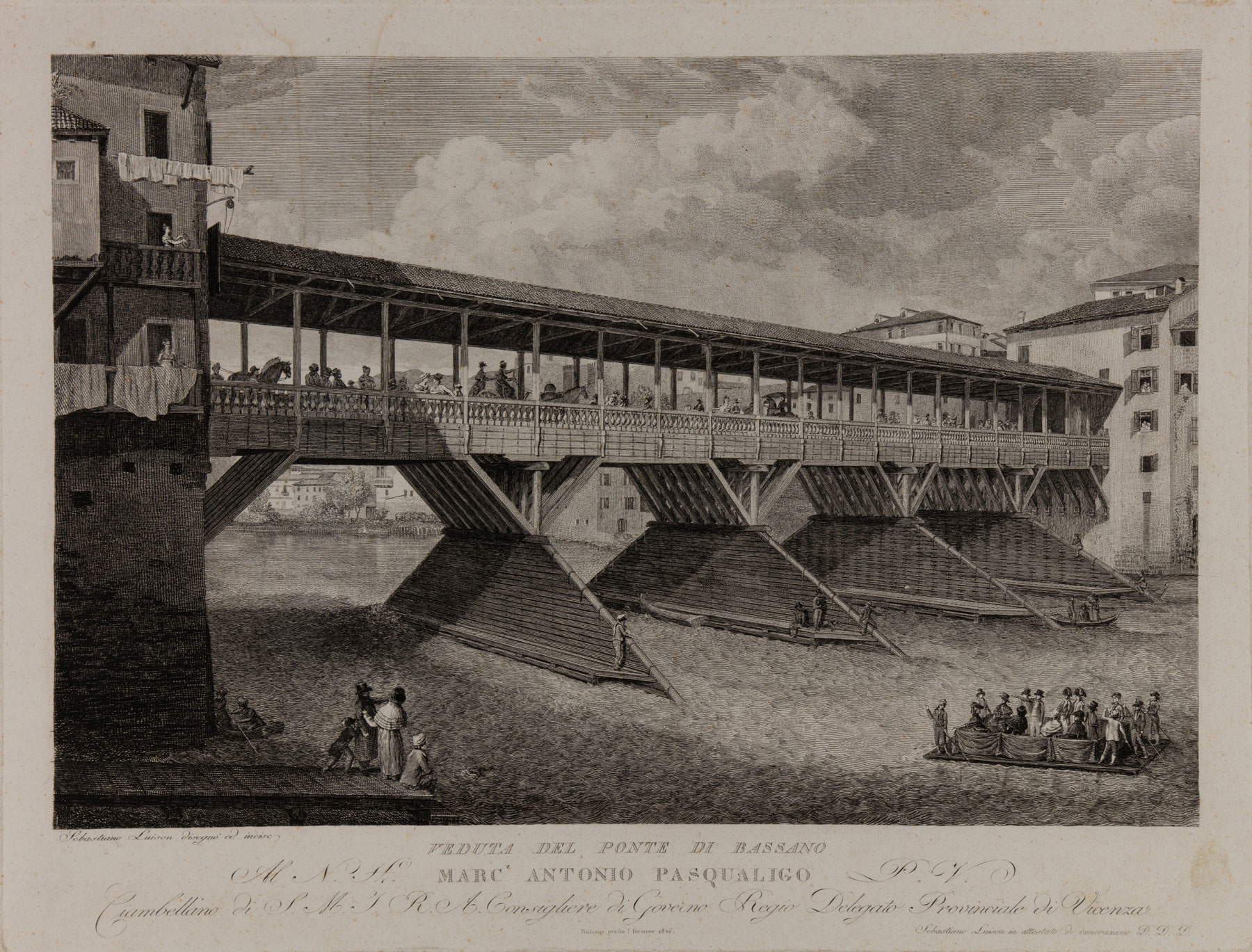

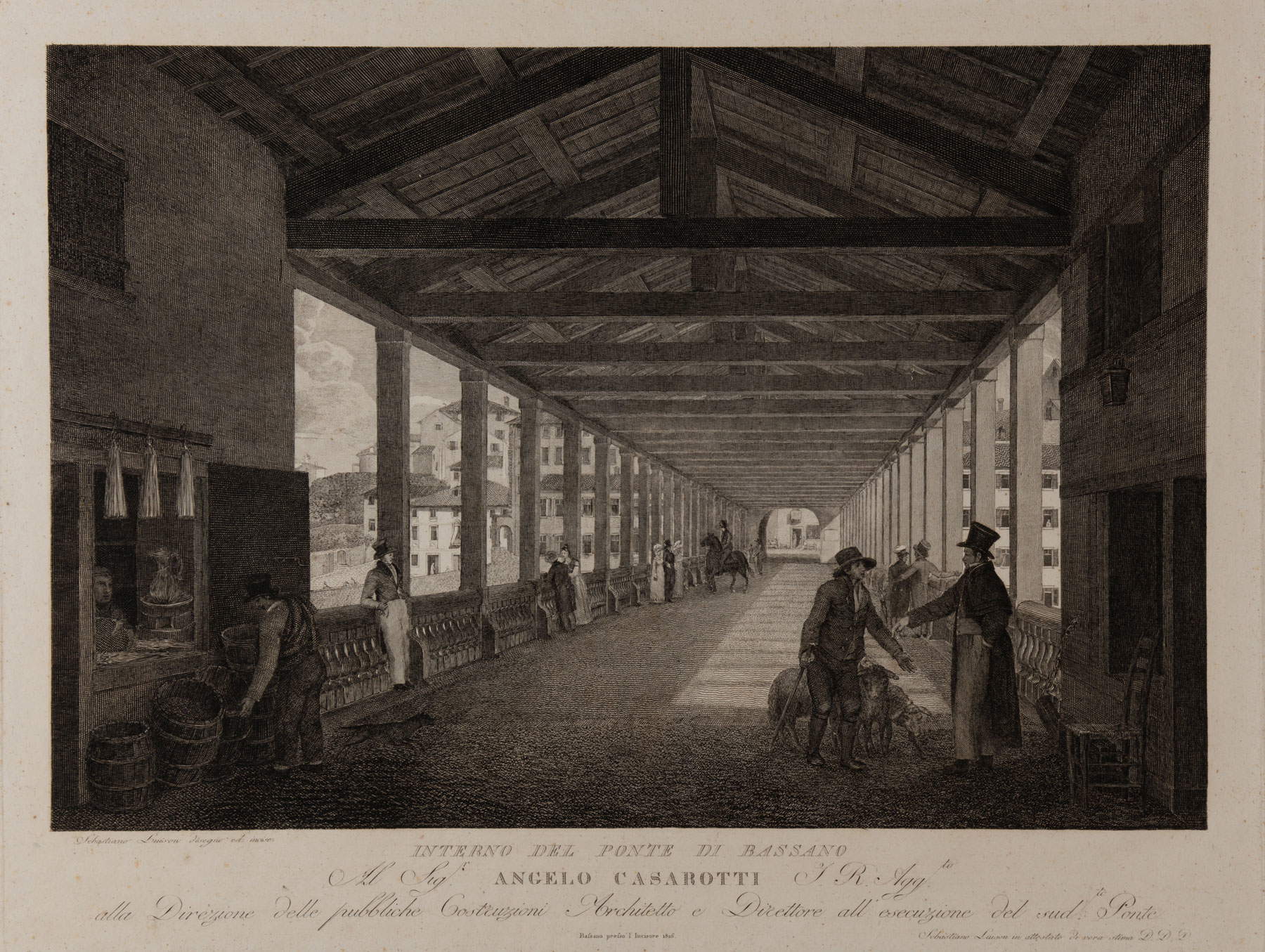

After work began, the architect returned to Bassano at least once: his last documented visit is on October 26, 1569, the date on which Palladio received a payment of 33 lire and 16 soldi “per el modelo” and to “veder la fatura del ponte.” In the end, the bridge was entirely similar to its predecessor: four spur stiles over the river and a roof with a pitched roof, supported by Tuscan columns. Palladio’s most “innovative” role, however, Battilotti explains, was expressed in the introduction of new technical and structural solutions.

|

| Sebastiano Lovison, Ponte Vecchio di Bassano (1826; burin, 330 x 430 mm; Bassano del Grappa, Museo Civico, INC. BASS. 392) |

|

| Sebastiano Lovison, Interior of the Ponte Vecchio di Bassano (1826; burin, 330 x 430 mm; Bassano del Grappa, Museo Civico, INC. BASS. 393, dedicated to Casarotti) |

|

| The Ponte Vecchio in Bassano today. Photo by Patrick Denker |

|

| The Ponte Vecchio of Bassano today |

Palladio’s bridge, however, did not survive the fury of the Brenta either, but it managed to hold out for two centuries until, on August 19, 1748, it was swept away by another violent flood, to which the Venetian man of letters Gasparo Gozzi also dedicated a poem: “It has been six days and more, that hand by hand / I have no other news in my head. / In the mountains it has been so great a storm, / And so much rain has poured down to the plain, / That it has unhinged the bridge of Bassano, / And carried it away like a basket. / Always I have fifty behind and in front, / That say: ha tu udito? What was that? / I answer them full of dira and spite. / The Bassano bridge is ruined: / The Bassano bridge, poor thing. / The Bassano bridge sè drowned.” After the disaster only the spur upstream of the second pier remained standing: everything else had been dragged by the river along the banks. So the same old rut was renewed: discussions about reconstruction and, in the meantime, ferry service between the two banks. Again it was decided for a faithful reconstruction, entrusted to Bartolomeo Ferracina, especially since Palladio’s design was preserved and it was possible to follow it to the letter: the new bridge was inaugurated in September 1751.

Since that year, the bridge was destroyed twice more, but not by the effect of nature, but rather by the wretched hand of man: in 1813, in fact, Viceroy Eugene de Beauharnais gave orders to set it on fire during the Austro-French war (it was rebuilt in 1821 by Angelo Casarotti) and, after passing through World War I unscathed, it was destroyed between February and April 1945. Damaged first during an attack organized by partisans under the direction of the Allies (and during which a woman and a young boy lost their lives) to disrupt the withdrawal of German troops (who then in retaliation shot three partisans who were in prison right on the bridge), it was then finally razed to the ground by fleeing Nazis. It was rebuilt immediately after the war, again following Palladio’s design: and since among the laborers who rebuilt it there were also many workers who had served among the Alpini during the war (in addition to the fact that the National Alpini Association intervened substantially to contribute to the reconstruction), since then the Bassano Bridge has also been known as the “Ponte degli Alpini.” And today we can consider it almost as a symbol of human art and ingenuity that do not stop in the face of calamity or the destructive and thoughtless action of human beings.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.