In 1876, the Ministry of Agriculture, Industry and Commerce of newly united Italy decided, for the first time, to collect statistical data on the phenomenon ofemigration, which, in previous years, had already led tens of thousands of Italians to leave the country to seek their fortunes in other parts of the world. The statistics tell a reality made of impressive numbers: between 1876 and 1900 more than five million compatriots left the country, for an annual average of about 210 thousand Italian migrants. Numbers that grew significantly in the following two decades: between 1901 and 1920 the figure rose to almost ten million, for an average of 492 thousand migrants each year. These figures are all the more significant considering that at that time Italy had roughly thirty million inhabitants, half of today’s population. The exodus was concentrated above all in the regions of northern Italy: in the period between 1876 and 1900, the primacy of emigration belonged to Veneto, from where 17.9% of the total number of migrants left, followed by Friuli Venezia Giulia with 16.1%, Piedmont with 12.5%, Lombardy and Campania, both with 9.9% (the situation would be reversed in the first fifteen years of the twentieth century, when the regions with the largest number of departures were, in order, Sicily, Campania and Calabria). The United States, France, Switzerland, Argentina, Germany, Brazil, Canada and Belgium were the countries to which most of the flow of Italian migrants was concentrated. There is no official, reliable data on the period between the Unification of Italy in 1861 and 1876, when surveys began, but it is estimated that no less than one million Italians left the country during that time.

A series of concauses helped form one of the most important mass emigration phenomena in history. The wave that characterized the last two decades of the nineteenth century was driven to leave the country mainly as a result of the extremely severe agrarian crisis that hit Italy and Europe in those years: the increasing mechanization of agriculture, the development of more modern cultivation systems, the spread of better-performing fertilizers and the arrival on the European market of cheap wheat from America (North and South) and Russia thanks to the modernization of means of transport (these were, in fact, the beginnings of the globalization of the economy) led to a collapse in wheat prices that inexorably affected farmers on the Old Continent. In Italy the unfavorable conjuncture was then aggravated by the fact that the country found itself, a few years after Unification and for the first time, having to compete with other countries in different markets (for example, that of wine with France or that of citrus fruits with Spain), to come to terms with the persistence of extensive crops (especially cereals) at the expense of the specialized ones that would have been better able to withstand international competition, to cope with crises of individual crops due to diseases that affected them (rice paddies and the sericulture sector in the north were the main victims, and the olive tree in the south), to suffer the ruinous effects of the great campaign of selling state assets and public securities that began in those very years (many landowners were attracted by the possibility of grabbing real estate and by the profit possibilities offered by the high interest rates on government bonds, with the consequence that they preferred to invest in the purchase of assets and securities, rather than in the improvement of land work systems: this is what emerges from a famous and thorough agrarian survey that was chaired by Senator Stefano Jacini and took seven years, from 1877 to 1884, to complete). What was more, to make matters worse, since the years immediately following Unification, was the gradual increase in the tax burden, because united Italy needed revenue to be able to build infrastructure. Rural society had then undergone new “processes of transformation in a capitalist sense of social relations in the countryside,” which “created new family and individual fortunes” but at the same time “generated unprecedented imbalances within rural society” (so historian Piero Bevilacqua): a consequence of this phenomenon was, for example, the erosion of peasants’ rights and the precarization of their work.

The economic causes were then linked to unprecedented reasons of a social nature: for example, women workers, who abandoned domestic work to go and swell the ranks of those who worked in factories, matured a perception of their condition that they had never had before (this topic was also discussed on these pages in an article dedicated to the artists who depicted women’s work in the same years). The same was true of the peasants who worked for the farms set up under the capitalist regime, especially in northern Italy, who began to demand better working conditions: Jacini himself, in the conclusions of his investigation, wrote that long ago “the rural plebs lacked a clear awareness of their economic inferiority; and, in their silence, it was licit to suppose that they were not ill; [....] Whichever way we turn, it is revealed that today agricultural Italy feels impoverished and looks dismayed at the future, which threatens to become worse than the present; it is noted that the landowners declare that they are no longer able, with the landed incomes from the same property as before, to conduct the same method of life as before; it is noted that a large part of the rural plebs burst into high laments.” In essence, a growing climate of distrust was accompanied by hopes of improving one’s living conditions as a result of moving abroad. And such hopes were heightened by the fact that in many foreign countries, especially in North and South America (and notably in the United States, Brazil and Argentina), there were plenty of sparsely populated territories in need of labor (and as a result these countries had launched real “campaigns” to attract European migrants).

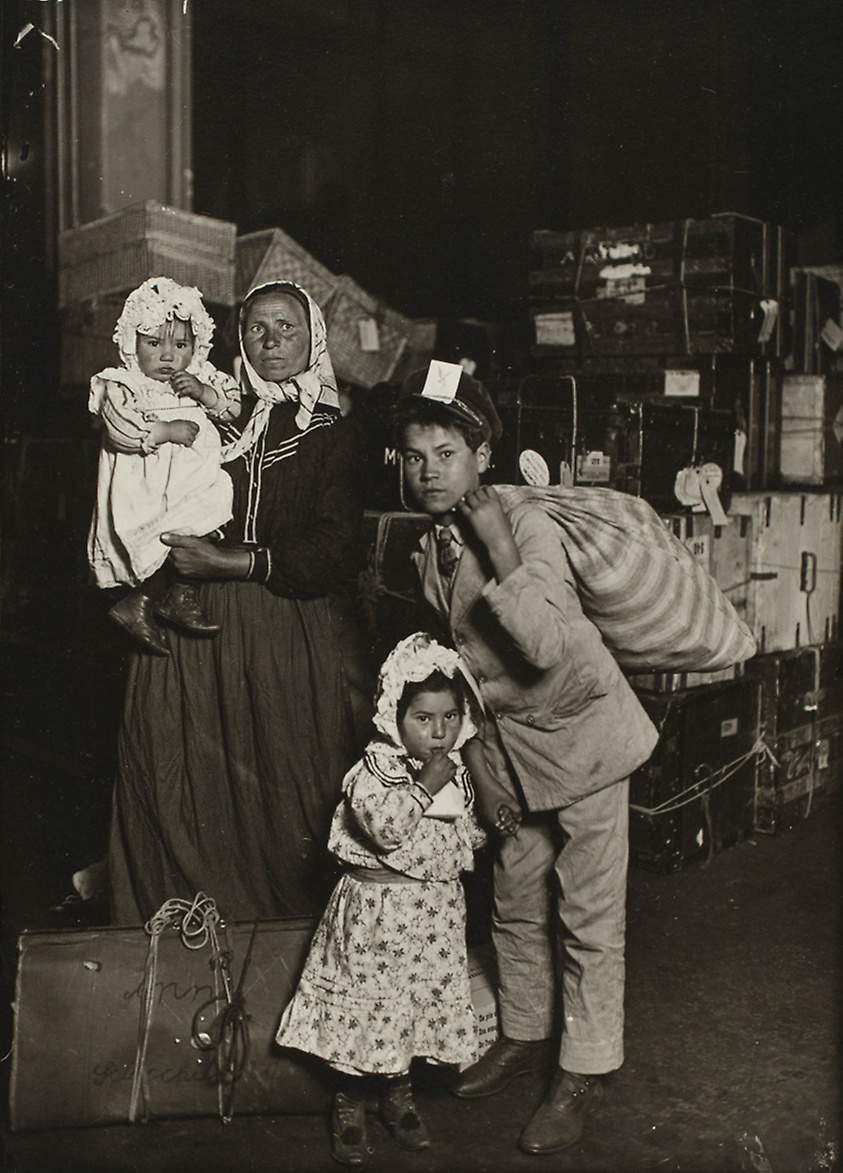

|

| Lewis Hine, Italian family searches for lost luggage at Ellis Island (1905) |

|

| Unknown photographer, Emigrants at Ellis Island wait for the ferry to arrive in New York (ca. 1900) |

These were the main reasons why hundreds of thousands of Italians left the country. Those who left for the Americas, of course, had no other means than the ship to reach their coveted destination: the largest port of emigration was Genoa (although in northern Italy there was no shortage of those who preferred to embark at Le Havre in France: paradoxically, for a Piedmontese of the time, with the transportation systems in force at the time, it was easier to reach northern France than Liguria), but ships loaded with migrants also departed from the ports of Livorno, Naples, and Palermo. The ports were not only the destination of migrants, however: some artists of the time, eager to denounce the plight of those who had chosen to leave the country (or had been forced to do so), began to frequent them in order to render on canvas the scenes they witnessed during the departures of sailing ships, steamers, and ocean liners. As is well known, the era of the great emigration also coincides with that period in the history of Italian art (roughly from the 1870s until the First World War) in which social verism imposed itself, often animated by unresolved underlying ambiguities (it was sometimes difficult to untie the knot about the artists’ intentions, and to understand whether they were moved by the desire to show commiseration and participation in the scenes they documented, or whether the latter were more or less clear political claims: “the inspiration that dominated these artists,” wrote Mario De Micheli, “was above all an inspiration of denunciation, founded, however, far more often on a feeling of pity than on a feeling of historical understanding of the proletarian or peasant movement of the time”), and which naturally provided for content to prevail over form, so much so that often a great many artists not directly ascribable to the verista movement nevertheless wanted to express themselves on the most pressing current social issues. Among the highest masterpieces of social verism, as well as among the works that best describe the theme of migration, are Gli emigranti by the Tuscan Angiolo Tommasi (Livorno, 1858 - Torre del Lago, 1923). The work, which dates back to 1896 (and is certainly not among the earliest on the subject) is set on a quay in the port of Livorno: in the background, sailing ships and steamers side by side, one after the other, are preparing to leave their moorings. The foreground, however, is all taken up by the migrant families crowding on the quay, in the quivering, anxious anticipation of departure. There are mothers holding hands with their children and others nursing infants, young and old conversing, we see a pregnant woman, there are those lying down to doze exhausted from waiting, there are those dragging some poor suitcases behind them, those simply sitting in silence, and there is, in the foreground, a woman looking toward us, drawing the attention of the relative to the scene, according to a typical expedient of Tuscan tradition. “The narrative,” wrote art historian Sibilla Panerai, “is epic in tone and the monumental measure, the photographic construction testifies to Tommasi’s sensitivity and commitment to social-print verism.”

Tommasi’s composition echoes a slightly earlier work, the Emigrants by the younger Raffaello Gambogi (Leghorn, 1874 - 1943), who in his early twenties, around 1894, produced his masterpiece and then presented it at the end of the year at the exhibition of the Società Promotrice di Belle Arti in Florence, as part of which he won an important prize, which brought Gambogi’s name to the attention of public and critics alike. The work was donated two years later by the painter to the City of Leghorn and is still in the city of Leghorn, kept at the “Giovanni Fattori” Civic Museum. Compared to Tommasi’s painting, which, as we have seen, was made a couple of years later (and it is entirely safe to assume that Tommasi was familiar with his young colleague’s work), Gambogi’s, also set at the port of Livorno, is imbued with more intense accents of sentimentality. The gaze focuses on the family at the center of the scene, consisting of a father, a mother, a girl and two small children: it is the moment of a touching farewell, with the father, moved, hugging his little girl, and with the two women of the house who are unable to lift their eyes, grieving. Beside them, other migrants sit on their trunks, amid bags and backpacks, waiting for the moment of boarding, which some, in the background, are already facing suitcases on their shoulders. The light that envelops the atmosphere is warm, but one cannot tell what season we are in: migration knows no good times and less good times. The gazes are not deepened, as is the case in Tommasi’s work, but appear undefined, because Gambogi is interested in suggesting the emotion of a moment, rather than describing a reality in detail: this is the main characteristic that separates his painting from Tommasi’s. On the one hand, a lyrical reading like Gambogi’s (and even the bags inserted in the foreground are functional in bringing out this aspect: luggage is the most obvious symbol of emigration at the end of the nineteenth century, and also represents on a metaphorical level the load of hopes that migrants carried with them), which focuses mainly on the expression of affections, and on the other hand, the more documentary nature of Tommasi’s.

|

| Angiolo Tommasi, Gli emigranti (1896; oil on canvas, 262 x 433 cm; Rome, National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art) |

|

| Raffaello Gambogi, The Emigrants (c. 1894; oil on canvas, 146 x 196 cm; Livorno, Museo Civico Giovanni Fattori) |

The families who flocked to the docks of the ports, moreover, were not well liked by the inhabitants of the port cities. Historian Augusta Molinari reports in one of her essays on a report by the Quaestor of Genoa, dated 1888, which states, “the disorder of emigrant families continues uninterrupted for some time now, who, having arrived in Genoa before the appointed day for embarkation, find themselves deprived of asylum and forced to spend the night under the porticoes and on the public squares with serious damage to the hygiene, morals and decorum of the city. A way must be found to put an end to this deplorable state of affairs.” And as a result, Molinari points out, the social representation that politics, newspapers and literature provided of migrants could only elicit “two reactions in public opinion: fear or pity,” with the former prevailing over the latter, especially in port cities. Describing this reality is a 1905 painting by Arnaldo Ferraguti (Ferrara, 1862 - Forlì, 1925), which went to auction in 2008: The Migrants is set in an urban foreshortening, with migrants sitting occupying the edge of a street. The theme was particularly felt by Ferraguti, who in 1890 had collaborated with the writer Edmondo De Amicis (Oneglia, 1846 - Bordighera, 1908) to illustrate Sull’Oceano, a novel about emigration, for the publisher Treves. Ferraguti’s work was also harshly criticized: it was born just at the time when the debate on verista art was in full swing, and an artist like Gaetano Previati (Ferrara, 1852 - Lavagna, 1920), who resented excesses in the use of the camera, lashed out against the illustrations of the then 29-year-old artist in a letter sent on October 29, 1891, to his brother Giuseppe, speaking of the "minchionatura d’illustrazione degli Amici di De Amicis and the other mystification ofOceano by our fellow citizen Ferraguti“ (the ”mystification“ for Previati was obviously not in the content but in the form: in his view, works such as Ferraguti’s were the result of an abuse of photography, which he called ”an odious abuse impudently gabellated as art to the naiveté of the good public as soon as its provenance could be disguised with a few touches of watercolor in the darks and boldly jagged in the background.")

And in fact Ferraguti, in order to create his work and at the explicit request of Emilio Treves, had made a journey on a ship of migrants that left in 1889 from Genoa for Buenos Aires: on the journey, the artist had brought with him not only canvases and brushes, but also a camera, so as to describe as accurately as possible the situations he would witness. The undertaking was far from easy, not least because of the migrants’ resistance. “I lasted all the pains in the world to persuade some of my fellow travelers to pose for my drawings and photographs,” the Ferrara artist would write. "I will say more, indeed. My albums or the lens of my camera spread such terror that if modern machine guns routed the enemy as I routed ’class passengers’ with my harmless and modest weapons, there would be no more carnage!" Many, on the other hand, were reticent thinking that Ferraguti was a policeman or something similar (emigrants included thugs who, by moving to another continent, hoped to avoid the course of justice at home), reasoning that whenever they saw the artist appear they tried to hide. Ferraguti succeeded nonetheless, and his illustrations are particularly valuable because they are among the very few works of art documenting the sea voyage. And as one can well imagine, the Atlantic Ocean crossings, which with the means of the time lasted more than a month, were anything but easy and comfortable: the passengers, especially the poorer ones, after buying a ticket whose cost, at the end of the 19th century, was almost always between 100 and 150 liras for a third-class voyage (a sum that corresponded, roughly, to three months of labor of a laborer), were first divided (men on one side, women and children on another: families thus slept in separate bunks) and then crammed into dirty, damp and foul-smelling dormitories, with poor and deficient sanitation, which encouraged the proliferation of diseases (lung infections, measles, malaria, scabies, tuberculosis and others, so much so that many migrants were turned away at the ports of arrival because of their poor health conditions, for fear that they would spread contagions), partly because when weather conditions were bad and it was not possible to get migrants onto the decks of the ships, the ship’s personnel did not have the opportunity to proceed with cleaning operations. It often happened that the ships were overloaded, with the result that the food supplies, obviously calculated according to the official capacity, soon began to run out (however, it should be specified that, as a rule, the food provided by the ships tried to be as varied as possible and was in any case almost always better than what the migrants were used to in their lands, and was often perceived as luxurious, also because of the abundance of meat). The prohibitive conditions (only from the early 1900s would they improve) caused frequent deaths, especially among young children. And it was not certain that the departors were certain of arrival anyway: shipwreck was an eventuality to be reckoned with. One of the most tragic was the shipwreck of theUtopia: the steamer, which had departed from Trieste, sank in the Bay of Gibraltar, following a collision with a British warship in stormy sea conditions, on March 17, 1891, on the 30th anniversary of the Unification of Italy, causing the death of 576 Italian migrants (just over 300 were those who managed to save themselves, however). Another 549 migrants, most of them Italians, disappeared when the Bourgogne, a French steamer that left Le Havre bound for New York, sank on July 4, 1898, off Nova Scotia, also after ramming another vessel due to fog that prevented optimal visibility. Another tragedy was that of the steamship Sirio, which left Genoa for New York: sailing too close to shore, the vessel ran aground in the rocks around Cape Palos (near Cartagena, Spain), and again the death toll was over 500.

|

| Arnaldo Ferraguti, The Emigrants (1905; tempera on paper, 35.5 x 37.5 cm; Private collection) |

|

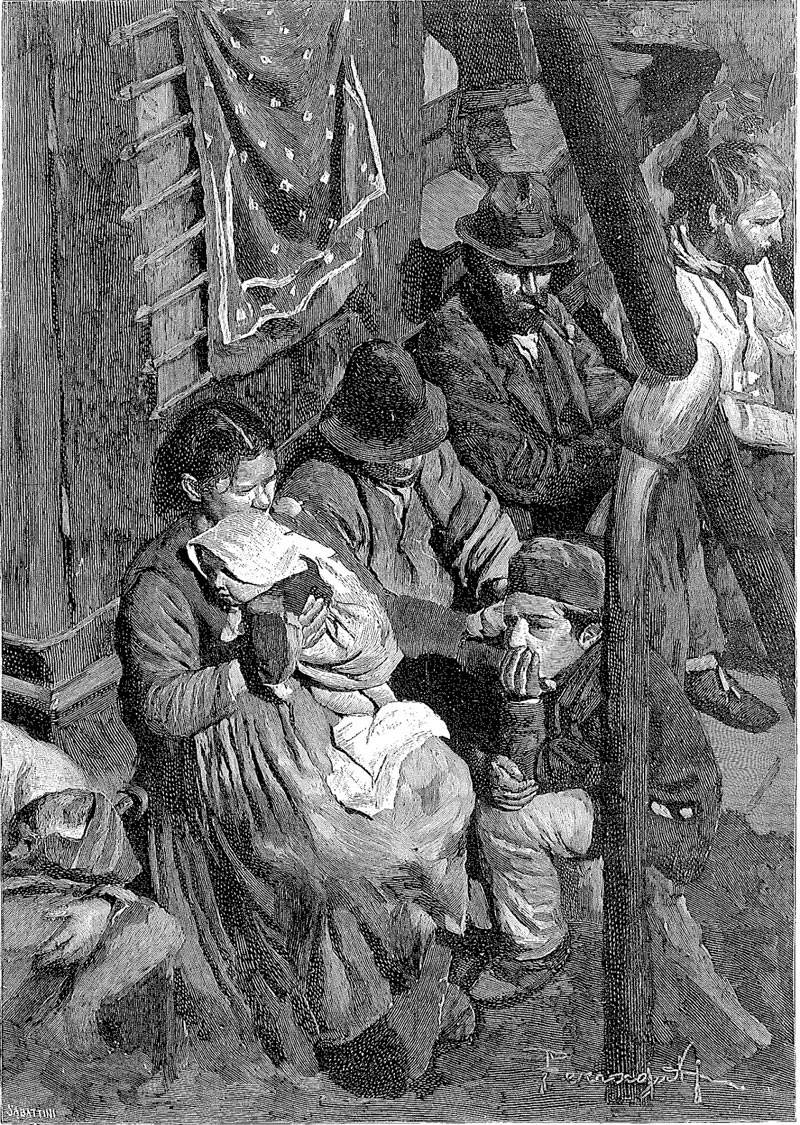

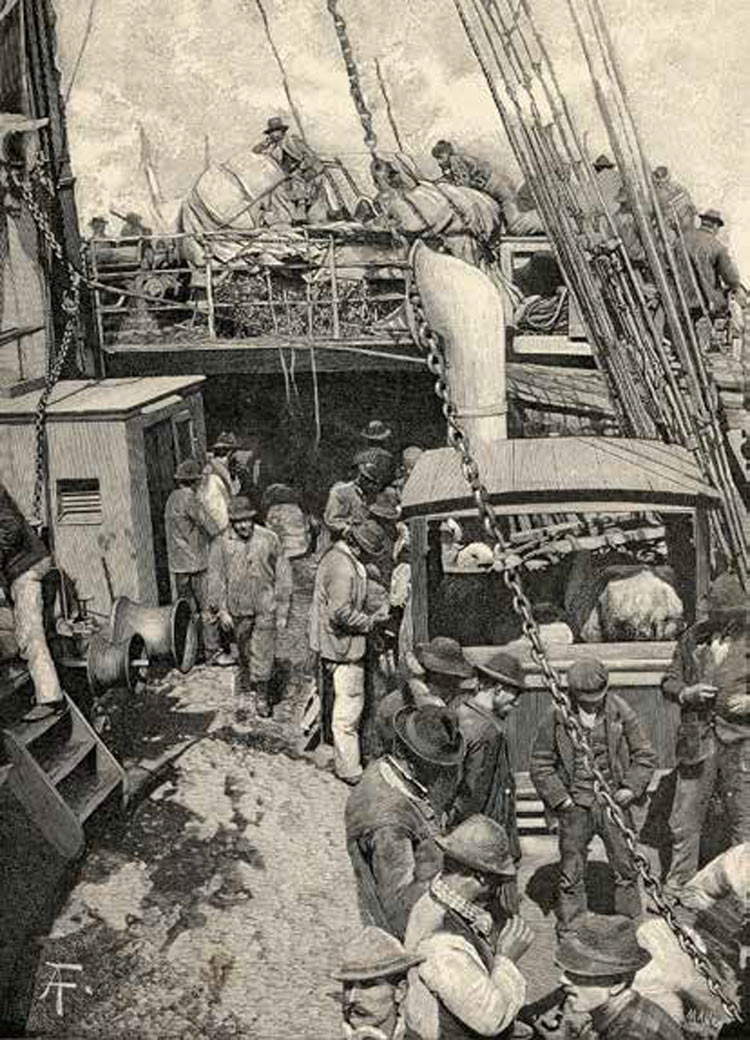

| Arnaldo Ferraguti, Illustration for Sull’Oceano by Edmondo De Amicis (1890) |

|

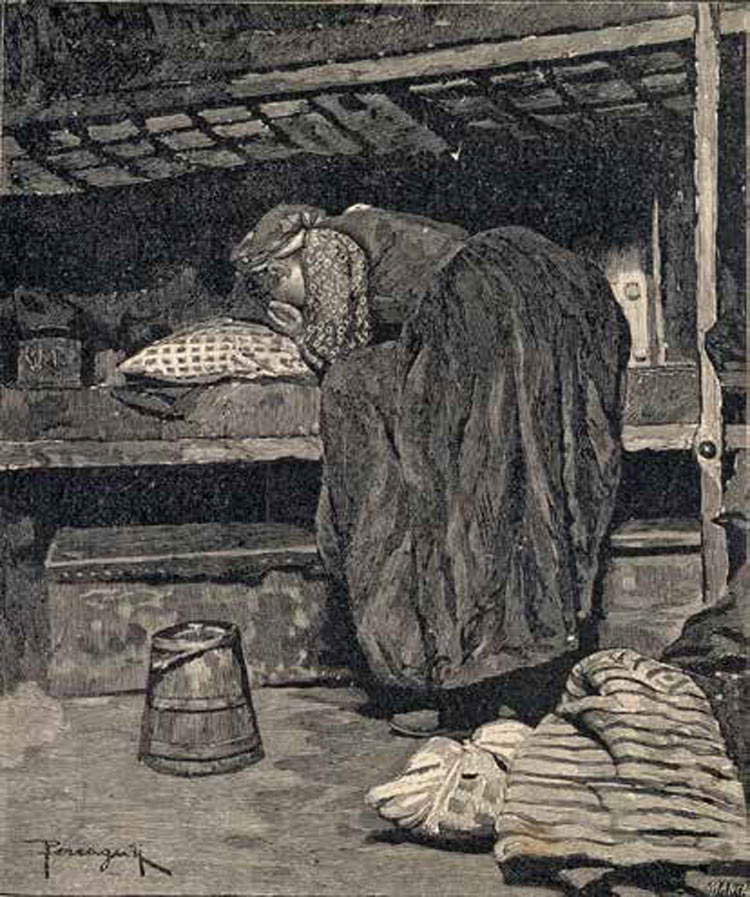

| Arnaldo Ferraguti, Illustration for Sull’ Oceano by Edmondo De Amicis (1890) |

|

| Arnaldo Ferraguti, Illustration for Sull’ Oceano by Edmondo De Amicis (1890) |

Among the artists there were also those who preferred to focus on the human and sentimental aspects of emigration, the same ones that many poets and literary men tried to bring alive in their writings, starting with the aforementioned Edmondo De Amicis, who also dedicated a long lyric to emigrants, Gli emigranti (“Cogli occhi spenti, con le guancie cave, / Pallidi, in atto dolororato e grave, / Sorreggendo le donne affrante e smorte, / Ascendono la nave / Come sascende il palco de la morte. / And each one on his trembling breast clasps / All that he possesses on earth. / Others a wretched wrapping, others a sorrowful / Child, who clutches / At his neck, from the immense waters terrified. / They ascend in long lines, humble and mute, / And over the faces appearing brown and haggard / Damp still the desolate distress / Of the extreme greetings / Given to the mountains they will never see again...” ), to continue with others such as Giovanni Pascoli (to emigration to America he dedicated the poem Italy), Luigi Pirandello (the theme of emigration emerges from some of his novellas, such as L’altro figlio or Lontano), Dino Campana, Mario Rapisardi, Ada Negri (in her lyric Emigrants, the poet addresses a Lombard bricklayer who leaves his land and his family: “The old story always new I all / read in the furrows and furrows that dig / your face, and in the hard hollow orbit / of your eyes, where every light seems destroyed. / You carry, in the sack on your shoulder, every good of yours; / but gathered on your chest you would have / your child, and give him, if he rises / and cries, a kiss, and the blood of your veins!” ). In the field of art, one of the most moving depictions of emigration is the painting Ricordati della mamma by Swiss Adolfo Feragutti Visconti (Pura, 1850 - Milan, 1924), painted between 1896 and 1904. Emigration also affected the Canton of Ticino: the first stop for Ticino migrants was usually the landing stages on Lake Lugano, from which boats shuttled to the Italian shores of the lake, where the journey would continue to sea ports. The scene described by Feragutti Visconti takes place on the pier in Gandria, a lakeside village a few kilometers away from Lugano. Here, a young mother wistfully greets her son who is about to leave: her gaze is confused and troubled, her gestures communicate all the sadness and poignancy of the moment, and the mother’s posture and mouth seem to suggest the phrase the painter chose as the painting’s title. The separation of families was after all a typical drama of those who migrated, for it was not certain that the whole family would leave for their destination. Feragutti Visconti himself, after presenting Ricordati della mamma at the 1903 Venice Biennial, wrote in a letter sent to the painter Abbondio Fumagalli, his friend, on May 9, 1903, that the painting “is extremely painful” (those who observe the painting can also easily see how Feragutti Visconti omitted any other narrative details so that the focus is entirely on the mother’s farewell). However, the work was received coldly (when not with derision) by critics: the point is that at the time, the themes of social verism were no longer in vogue, and as much as the drama of migrants was still highly topical, the work appeared laggardly in the eyes of critics. The fact remains that Feragutti Visconti’s is one of the most delicate and intimate paintings dedicated to the theme of emigration.

Also centered on the affections, but of a very different tone, is a sculpture by Domenico Ghidoni (Ospitaletto, 1857 - Brescia, 1920), which represents one of the artist’s masterpieces as well as one of the highest moments of social verism in the field of sculpture. Entitled Emigrants, the work was first presented to the public at Brera in 1891 and stood out for providing an unsettling representation of the theme in sculpture: before that time, single subjects abounded, usually depicted fatigued and with sad looks, but these could be interpreted in different ways, were it not for the titling that artists chose to give to these works. In contrast, Ghidoni’s Emigrants aimed to bring out the drama of those leaving their homeland, and was a good success at the Brera exhibition, even bringing back a prize. The artist had conceived the work as early as 1887: the subject of his sculpture is a mother with her teenage daughter, seated (and already exhausted: the little girl has fallen asleep) awaiting departure. With an affectionate gesture the mother caresses her daughter, but her gaze is pensive, probably already turned to the difficulties of the transoceanic crossing, or to anxiety about what will await them in the new world. Critical acclaim was unanimous: “Whoever looks at the figure of the woman modeled by Ghidoni,” wrote critic Pompeo Bettini, “thinks of the poem of courageous poverty. With an act of weary but resolute protection, that woman watches over a teenage girl who sleeps near her in a most natural pose of weariness, as one who, though in the time of early vexations, already knows the labors. The vision widens around this group, a very great merit for a sculpture. One thinks of the third-class passengers and their poor saddlebags, of the steamers that bring to America so much misery nourished by hope.” Praise also came from such a great artist as Vittore Grubicy de Dragon, who appreciated “the sincere emotion felt by the author both in dressing his concept and during the course of the execution.” Ghidoni’s plaster was cast only posthumously, in 1921: one of the two replicas that were made that year, in monumental form, was long exhibited in the gardens of Corso Magenta in Brescia, while it is now preserved at the Museum of Santa Giulia, where it has been sheltered to preserve it from the actions of atmospheric agents.

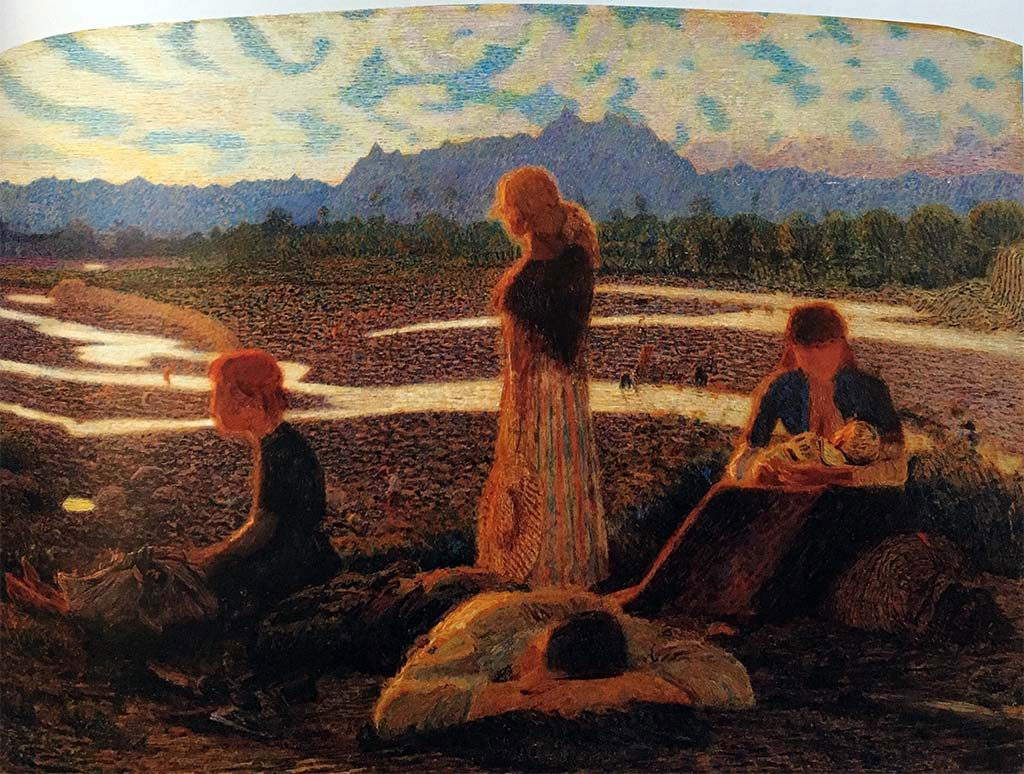

If many authors devoted their attention to the theme of embarkation to the new world, there was no lack of those who preferred to depict the first moments of departure, or focus on other types of migrations. To the first case belongs a painting by the Venetian Noè Bordignon (Salvarosa, 1841 - San Zenone degli Ezzelini, 1920), who with his painting The Emigrants, set in the Venetian countryside, depicts a family that, on a poor cart pulled by a donkey and with a few bundles loaded, has just left its village and is probably still unaware of what will await it (in fact, the faces appear fresh, and even a smiling girl appears). Of a far different tenor, however, is Tired Membra, also known as Family of Emigrants, the last work by Giuseppe Pellizza da Vol pedo (Volpedo, 1868 - 1907), which recounts the tribulations of seasonal migrants who temporarily left the mountains to work in the rice fields around Vercelli. The painting is unfinished since Pellizza took his own life before completing it (we see, in fact, that the faces of the characters are not defined) and had a long gestation (it was conceived as early as 1894, and sketched out a couple of years later): nevertheless, although unfinished, the painting recounts the theme of emigration with an unprecedented expressive power conferred by the harmonious juxtaposition between the melancholy of the characters, tired after a day’s work (the head of the family, exhausted, has been lying prone on the ground), and the magnificence of the landscape that is cloaked in the red tones of the sunset, for a result with an almost expressionist flavor, indicative of the evolution that Pellizza’s painting would have known if his existence had not been abruptly interrupted. Ultimately, some artists also painted the theme of returning home, either in dramatic tones or positively. Among the most tragic paintings is possible to include Giovanni Segantini ’s (Arco, 1858 - Pontresina, 1899) Il ritorno al paese natio (The Return to the Native Country ), a dramatic and poetic reflection on the saddest consequences of emigration, which was, moreover, awarded a prize at the first Venice Biennale in 1895: the work recounts the return, to the native village in the mountains, of the body of an emigrant, probably a castaway, carried on a horse-drawn cart, escorted by a man and accompanied by a weeping woman. Happy return, on the other hand, is the theme of Torna il babbo, a painting by Egisto Ferroni (Lastra a Signa, 1835 - Florence, 1912), dated 1883, which depicts the reunion of a family following the return of the father: smiles, relieved faces, a feeling of happiness. The work also helps to highlight two aspects of Italian emigration at the end of the 19th century: in the first wave (until 1885) it was a phenomenon that involved mostly males (the departors were usually in the proportions of one woman for every five men), but in the last years of the century the percentage of women increased to 25 percent, and the numbers balanced out near the First World War. The second aspect is the number of returns: in particular, in the first twenty-five years of the twentieth century, about one-third of those who had left Italy to move to America returned home.

|

| Adolfo Feragutti Visconti, Ricordati della mamma (1896-1904; oil on canvas, 154 x 116 cm; Milan, Fondazione Cariplo) |

|

| Domenico Ghidoni, Emigrants (1891; bronze, cast 1921, 127 x 180 x 93 cm; Brescia, Museo di Santa Giulia) |

|

| Noè Bordignon, The Emigrants (c. 1896-1898; oil on canvas, 174 x 243 cm; Montebelluna, Veneto Banca) |

|

| Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo, Tired Membra (1904; oil on canvas, 127 x 164 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Giovanni Segantini, Ritorno al paese natio (1895; oil on canvas, 161 x 299 cm; Berlin, Staatliche Museen, Nationalgalerie) |

|

| Egisto Ferroni, Torna il babbo (1883; oil on canvas, 137 x 87 cm; Rome, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea) |

The theme of emigration began to disappear from the “radar” of Italian painters around the 1910s, but the phenomenon did not stop, quite the contrary. Certainly, travel conditions had improved markedly, but separation from one’s homeland and one’s affections was still a drama, and the numbers of departures continued to be substantial for much of the 20th century. Historian Gianfausto Rosoli, a specialist in the history of emigration, has calculated that in one century, from 1876 to 1980, more than 26 million Italians left the country: of these, 16 left before 1925 (it was mainly the first two decades of the twentieth century that saw the largest number of people leave). A phenomenon that, given due proportion and considering the changed economic, cultural and social contexts, still continues today: Italy today is not only a land of arrival for many migrants (a transformation that our country has undergone since the 1990s), but it is still, albeit to a lesser extent than in the past and with totally changed logics in the dynamics of flows, a country from which people leave. Between 1997 and 2010, according to data collected by Istat, there were 583,000 Italians who chose to expatriate, and in 2017 alone the number of Italians who emigrated amounted to 114,559. The phenomenon today mainly concerns young people: one in five Italian emigrants is under 20 years old, two in three are between 20 and 49 years old, and the average age is 33 for men and 30 for women. The flow is mainly made up of citizens who have medium-high educational qualifications: in 2017, there were 33,000 high school graduates and 28,000 college graduates who left the country. Radically different stories than those of the late 19th century, different means, different economic availability, different social classes, different culture, impossible comparisons, but the same hope, both for those leaving and for those arriving or returning: that of trying to create a future for themselves.

Reference bibliography

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.