Is contemporary art really for everyone or is it only for educated and niche audiences? And what happens when contemporary artwork is displayed among the streets and squares of our cities?When we talk about site-specific contemporary artwork, we refer to works conceived and designed for a specific environmental, cultural and social context in which such works will be placed and exhibited, temporarily or permanently. The artist’s intervention is made according to a dialogue established with the chosen context and its audience, with the idea, a priori, of being enjoyed and enjoyed by the observer and, therefore, by those who, even casually, find themselves in front of it.

Unlike the site-specific artwork, which was created for an exhibition project within museums and galleries,site-specific public artworks fit into a context experienced bya heterogeneous public, which does not choose to witness a cultural operation and which, in most cases, does not possess keys to understanding it. It is necessary, therefore, that the design of a work of public art involves not only the analysis of the context in which it is to be inserted but also a careful reflection on the message to be conveyed to the public.The artist is, in this case, responsible for a transformation of the landscape on which he intervenes and must avoid the self-referentiality of his gesture. Successful operations can, on the other hand, be defined as those that interact effectively with the community that welcomes them and recognizes them as part of their urban context.

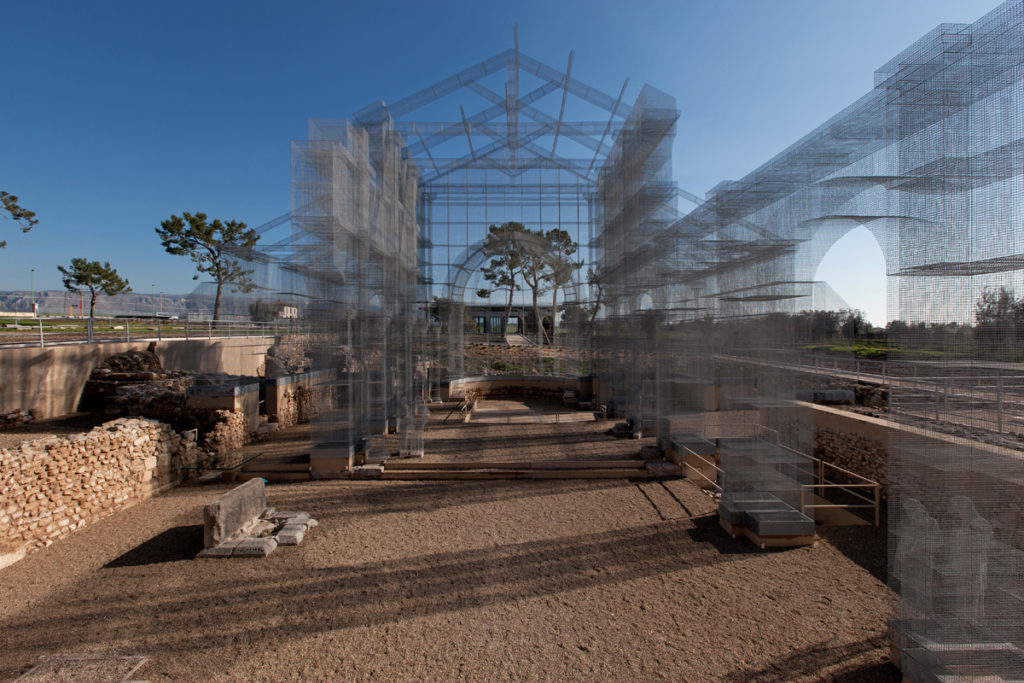

They represent virtuous cases, in this sense, the structures of Edoardo Tresoldi, such as the reconstruction of the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in Siponto, which allowed the public not only and no longer an abstract knowledge of the early Christian basilica, destroyed over the centuries, but also the direct experiencewith a fully accepted and usable architecture.

Burri ’s Cretto in Gibellina, the largest work of land art in Italy, represents another excellent case. The concrete pouring over the street layout of the old town, destroyed by the earthquake, stands as a white veil over the rubble and the cries of pain of the inhabitants. The work, here, becomes an emblem of memory and an element of identity of the territory, acquiring ipso facto a considerable symbolic and cultural value.

Among the most debated cases, however, is Michelangelo Pistoletto’s reintegrated Apple, placed in 2016 in front of Milan’s Central Station. Despite bearing the signature of one of the Italian masters of contemporary art, the work was not appreciated by the public, who considered it lacking a connection with the city, an element alien to the urban context. Already in 2011, at the same location, another work, Ian Ritchie’sSunrise in Milan , had caused discussion with its 30-meter height, to the point of causing its removal just a year later because it was considered, by the same city administration that had promoted it, a visual stumbling block for the station’s facade. Also in 2011, aanalogous operation occurred in Rome at the Piazza dei Cinquecento, again opposite the main train station (the doubt arises that stations are unlucky places for public artworks). Oliviero Rainaldi ’s monument to Pope John Paul II was immediately the subject of criticism, and the then mayor of Rome called for a new version that was later completed in 2012. The artist’s intention to portray the pontiff departing from classical iconography and with a large bronze sculpture, in an ideal embrace of the faithful, convinced neither pilgrims nor the citizens of Rome, and the work, today, is ranked by some as one of the ugliest monuments in the world.

|

| Edoardo Tresoldi, Where Art Reconstructs Time (2016; electrowelded wire mesh; Manfredonia, Siponto Archaeological Park). Ph. Credit Blind Eye Factory |

|

| Alberto Burri, Grande Cretto (1984-1989; concrete and remains, 150 x 35000 x 28000 cm; Gibellina) |

|

| Michelangelo Pistoletto, Mela reintegrata (2015-2016; metal, plaster, marble dust, 800 x 700 cm). Ph. Credit Luoghi del Contemporaneo - Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities and Tourism. |

|

| Ian Ritchie, Dawn of Milan (2001; fiber optics, height 3000 cm). Ph. Credit Ian Ritchie Architects |

|

| Oliviero Rainaldi, Monument to John Paul II (2011; bronze, height about 700 cm; Rome, Piazza dei Cinquecento) |

Controversy, however, is also sometimes useful in consolidating the presence of artistic interventions in urban areas, as happened with Maurizio Cattelan’s L.O.V.E.(Liberty Hate Revenge Eternity). The work, temporarily placed in front of the Milan Stock Exchange building, depicts a hand in a fascist salute with fingers sliced off apart from the middle one: an explicit message against the blind venality of the economic market. The debate that arose upon its appearance involved various cultural figures and led to the city administration’s decision to keep it permanently in its location.

Additional issues affecting site-specific public art interventions are their protection and preservation. The works and installations, with particular regard to those en plein air, require an economic, as well as cultural, project that provides for and sustains over time their maintenance, which is usually entrusted to the relevant administration that has precise needs to plan in advance the necessary resources. To this end, the General Directorate for Contemporary Creativity of the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities and Tourism contemplates among its tasks that of supervising the application of Law 717/49 and known as the 2% law, which requires all public entities, to allocate a percentage of the amount of works of art in newly constructed public buildings. In fact, when an art proposal does not include a provision for the expense of its maintenance, one runs the risk of seeing the works deteriorate over time and the resources expended in its creation go in vain. It is desirable, therefore, that a project be designed and implemented in a sustainable way, both economically and temporally, to ensure its continuity and protection. The exceptions to this are those interventions that originate as free gestures in public areas (as is the case with street art) in which the works are created with the intention of being transitory and not involving preservation and musealization activities.

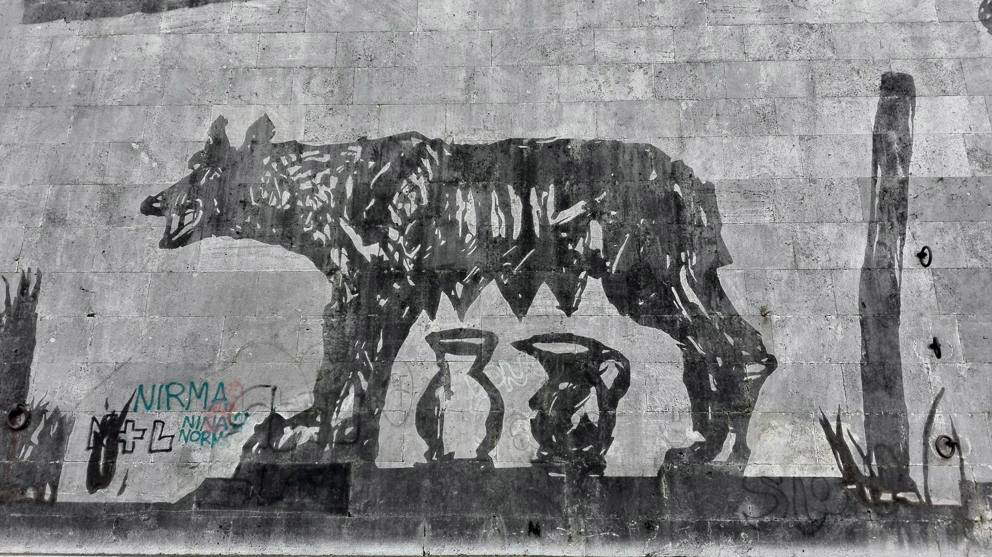

Think of Banksy ’s works or William Kentridge with his Triumphs and Laments, a mural work placed along the Tiber River in Rome. Kentridge creates a large ephemeral installation by cleaning up the biological patina present on the travertine and creating negative figures that narrate the history of Rome. The work is destined to disappear and so, by the artist’s choice, will be remembered only through photographic documentation.

In 2017, Giuliano Mauri’s Vegetable Cathedral was inaugurated in Lodi, costing the Lombardy Region almost 300,000 euros, supported also by the financial contribution of private individuals. The environmental installation, built on the design of Mauri (who passed away in 2009), consisting of 108 wooden columns 18 meters high, suffered damage due to weathering and eventually structural failure caused by biological attacks on the structure, an unforeseen event that was probably not contemplated at the design stage and for which legal verifications are currently underway. In 2019, the installation, in an advanced state of disrepair, was finally torn down. It is just these months, however, that news of its probable reconstruction as a symbol of the city of Lodi and posthealth emergency rebirth from Covid-19.

There are several public art interventions that could be mentioned, extending the reflection to large architectures as well. Think, for example, of the glass and metal pyramid structure of the Louvre entrance, designed by Ieoh Ming Pei, without which, today, we could not imagine the museum’s entrance. Think also of the MAXXI building in Rome, designed by Zaha Hadid, which was conceived as a work in itself before it was even a museum and which has redeveloped the entire neighborhood to such an extent that it has affected the real estate market. These are cases in which the work (the architecture) becomes an integral part of its host environment, fully interacting with the urban fabric.

|

| Maurizio Cattelan, L. O.V.E. - Liberty Hate Revenge Eternity (2010; Carrara marble, height 1100 cm; Milan, Piazza Affari). Ph. Credit Luoghi del Contemporaneo - Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities and Tourism. |

|

| William Kentridge, Triumph and Laments, detail (2016; mural, approximately 550 m long; Rome, Lungotevere) |

|

| Giuliano Mauri, Vegetable Cathedral (2017, posthumous; wood, 1800 x 7200 x 2248 cm; formerly in Lodi, Ex Sice Area, to be torn down in 2020) |

|

| The Louvre Pyramid, a project by Ieoh Ming Pei |

|

| Rome, the MAXXI headquarters, design by Zaha Hadid |

|

| Mario Cucinella’s proposal for the facade of San Petronio in Bologna. |

But how far can the artist go? What is the limit between artistic intervention and landscape disruption? When is the intervention to be considered art and not rather an architectural and artistic superfetation that could be done without? Finding a match by looking back to the past is only possible by analyzing the presence of sculptures in city squares that, however, served celebratory and commemorative functions. What function, then, does public art serve today?

These days the proposal by architect Mario Cucinella to complete the facade of the Basilica of San Petronio in Bologna,unfinished for centuries, with a plant installation is news. Since the 16th century, the facade remained incomplete due to lack of funding and stylistic disagreements on the project to be executed. Is it possible, then, today almost five hundred years later to take responsibility for such a choice, transforming the original, albeit incomplete, setting?

Archistar Cucinella’s idea, which appears as an interesting provocation on unfinished architecture in Italy and the abandonment of buildings and urban projects, should make us reflect on the alteration of the landscape and its consequences.

In the light of so many and diverse testimonies of public art, it seems clear that landscape and urban transformation can only be accepted and justified if there is a true dialogue and formative exchange between art, urban context and the public, thus fulfilling a specific function: to sensitize communities to art, to culture for the development of a conscious and considerate people, not only towards artistic expressions, but also towards social and cultural diversity.

It is, however, more than appropriate to carefully consider the feasibility and sustainability of public art installations, opening specific debates in the communities concerned, to define not only their design relevance, but also questioning conservation and maintenance issues, remembering that in a hundred years our civilization and culture, will also be evaluated through urban morphology and artistic interventions... as long as they are still there.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.