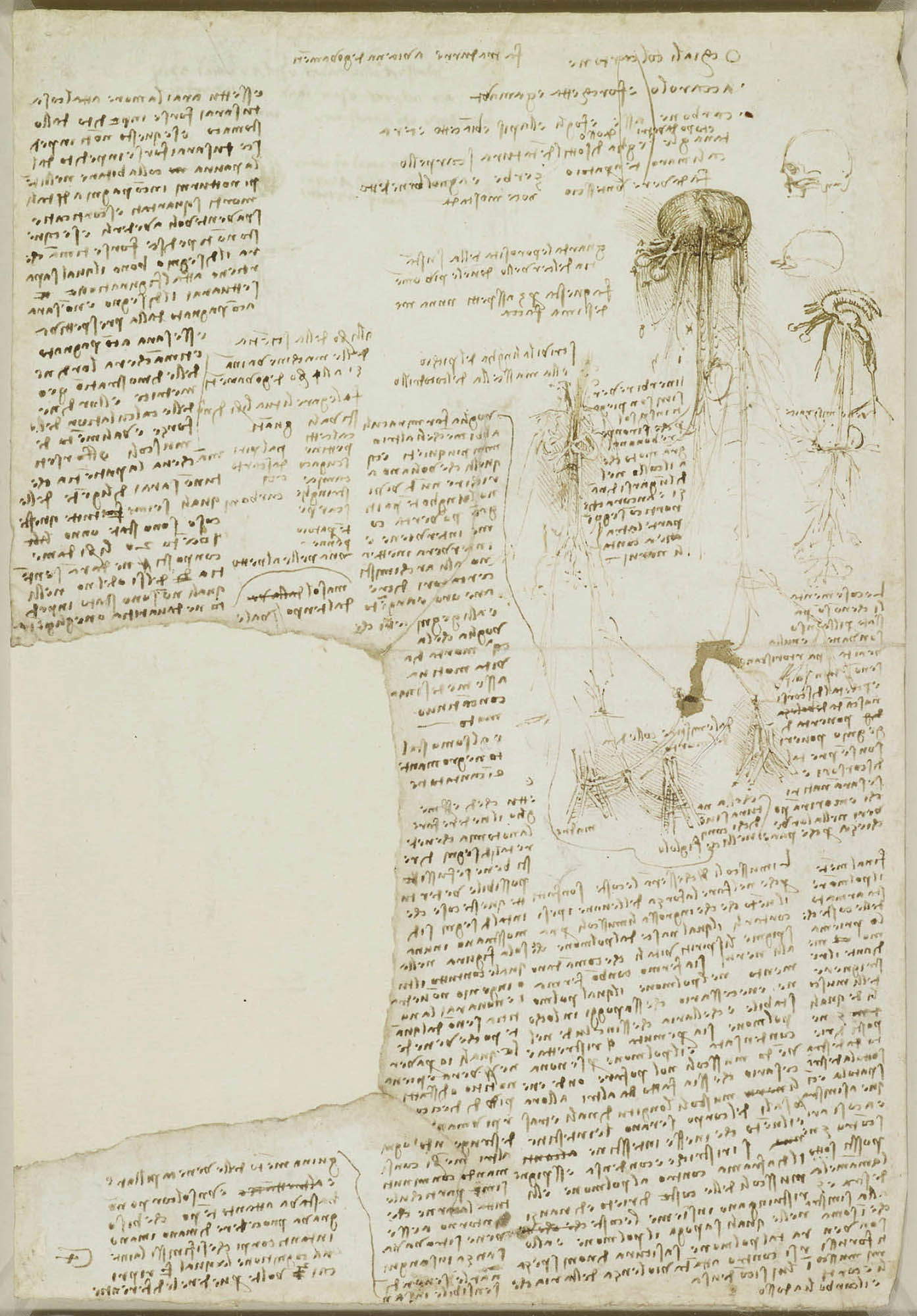

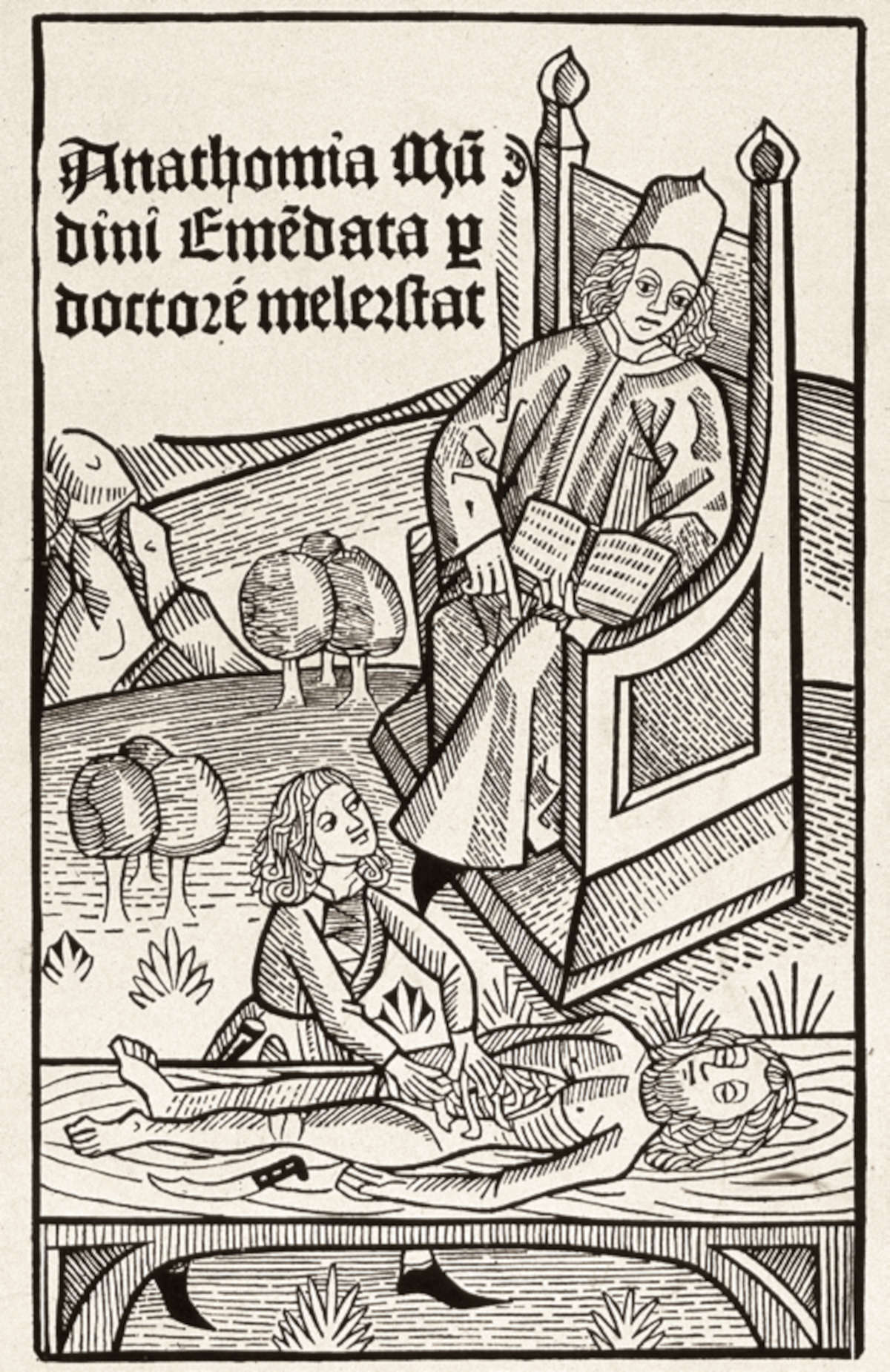

In a paper preserved at the Royal Library, Leonardo da Vinci writes that, in order to be able to accurately draw the veins of the human body and have “full knowledge of them,” he had “disposed of more than ten human bodies, destroying every other member, consuming with minutest particles all the flesh that d’intorno a esse veins was found.” It is known, by Leonardo’s own admission, that the great Tuscan artist devoted himself to dissecting corpses, a relatively recent practice since it had been performed since at least the 13th century but had been codified as a tool of scientific investigation by a Bolognese physician, Mondino de’ Luzzi, in the 14th century. It was in 1316 when Mondino composed his treatise on anatomy, the Anathomia Mundini, which can be regarded as the first in which human anatomy is described according to a mediation between direct observation and knowledge gleaned from ancient texts: in fact, before the practice of dissecting corpses was introduced in European universities, knowledge of anatomy was mainly derived from reading the texts of ancient physicians, above all the text of the Greek physician Galen, who lived between the second and third centuries. However, Galen’s text would remain a point of reference for a long time to come, as Guido Beltramini, Francesca Borgo and Giulio Manieri Elia, curators of the exhibition Modern Bodies (Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia, April 4 to July 27, 2025), write: “Until the end of the fifteenth century,” reads their introduction to the exhibition catalog, "knowledge of the anatomy of the body passed through the reading of an ancient Greek text, Galen, carried out by the professor while a barber dissected the corpse. In the frontispiece of The Body Factory of 1543, however, it is the hands of Andrea Vesalius, the physician who authored the book, that open the belly of the corpse. The unveiling of the body, in contrast to bookish knowledge, reveals it for what it is, not as it is described on bad translations of the classics."

The deepening of the body by doctors and scientists, the three scholars continue, "produces new knowledge, which needs new forms and new languages, which science does not yet have. It will seek them out on the one hand by recovering the language of ancient art, as Vesalius does by depicting torn bodies as ancient statues. On the other by giving birth to a laboratory that produces different solutions: from seeing through the body made transparent as in Leonardo’s ’Great Lady,’ to Vesalius’s seeing within, to seeing in succession of anatomical prints, with liftable flaps, or popular ivory openable manikins." At the origins of this revolution thus stands the Flemish physician Andrea Vesalius (Andreas van Wesel; Brussels, 1514 - Zante, 1564), but the new science of the body he introduced, made possible by a systematic practice of dissecting cadavers, would perhaps not have been possible without the ground prepared by artists, beginning with Leonardo da Vinci himself (Vinci, 1452 - Amboise, 1519), for whom perhaps the very term “artist” might be reductive. Vesalius’ is a central figure in the history of medicine and science: his work marked a definitive turning point in the understanding of human anatomy. Born into a family of medical tradition, Vesalius became a major player in the scientific Renaissance, breaking with the long tradition that relied primarily on the authority of ancient texts and Galen’s anatomical theory, which had dominated medicine for more than a thousand years. His most famous work, De humani corporis fabrica (1543), not only revealed the human body as it had never been seen before, but also changed the way science was practiced and represented, influencing medicine, art, and science education for a long time.

Prior to Vesalius, understanding of the human body had been transmitted, as mentioned, through the texts of Galen: his writings were considered the basis of anatomical knowledge, but they were done without direct dissection of human bodies, since Roman laws forbade it. Galen, in fact, had mainly studied animals (apes, in particular: In fact, Galen believed that there were no major differences between the human and ape bodies), and he had become almost a mythical figure for medieval and Renaissance physicians, so much so that his errors were rarely questioned. Vesalius’ approach was radically different: the Flemish physician promoted the idea thatdirect observation of the human body was essential, a view that resulted in an intensive program of dissections on cadavers.

The treatise De humani corporis fabrica was the fruit of years of research and dissections, in which Vesalius not only corrected Galen’s errors but proposed a new anatomical vision, based on evidence and direct experience. This book, distinguished by its visual magnificence and scientific precision, was published in 1543 in Basel and marked a milestone in the history of medicine. Its anatomical plates were drawn with such precision that modern science would not be able to do without these images for a long time.

We do not know for sure who made these plates. Giorgio Vasari attributed them to a German artist, Johannes Stephan van Calcar (Kalkar, 1499 - Naples, 1546), whose sensibility was close to that of Flemish artists: given his extreme precision, and given that we know that Vesalius, in 1538, published at least three plates based on Calcar’s drawing (and furthermore, the physician also had his portrait painted by Calcar), the German artist can be considered the leading candidate for the Fabrica plates. Another artist associated with these plates is Domenico Campagnola (Venice, c. 1500 - Padua, 1564), but what matters most is the content of the plates. Beginning with the one that adorns the title page of the first edition of the Fabrica, published in 1543: in a university anatomical theater, such as the one active in Padua from 1497 onward (and later becoming permanent in 1594: it is the one that can be admired today in the Palazzo del Bo), the lecturer, for the first time, abandons his chair to directly dissect the cadaver in front of his students. In this case, the corpse is that of a woman: for these operations, the corpses of executed people were usually used, often dissected the same day the sentence was carried out.

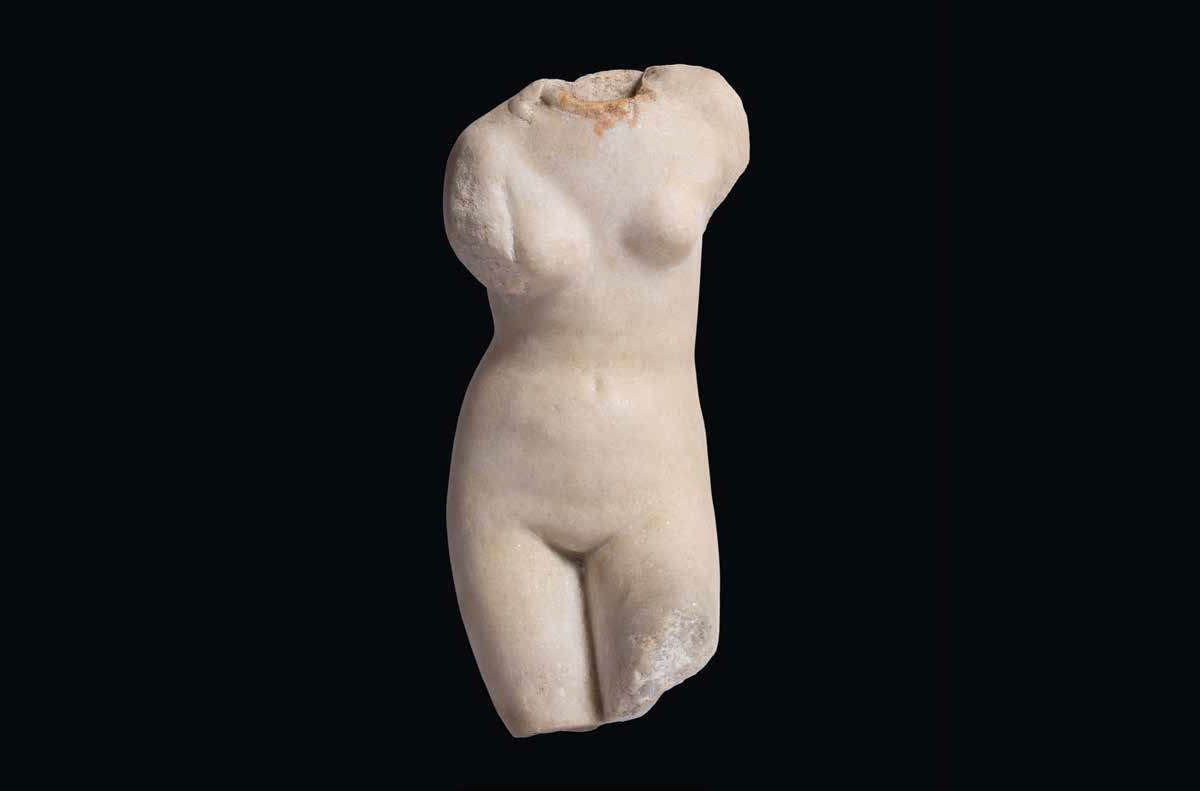

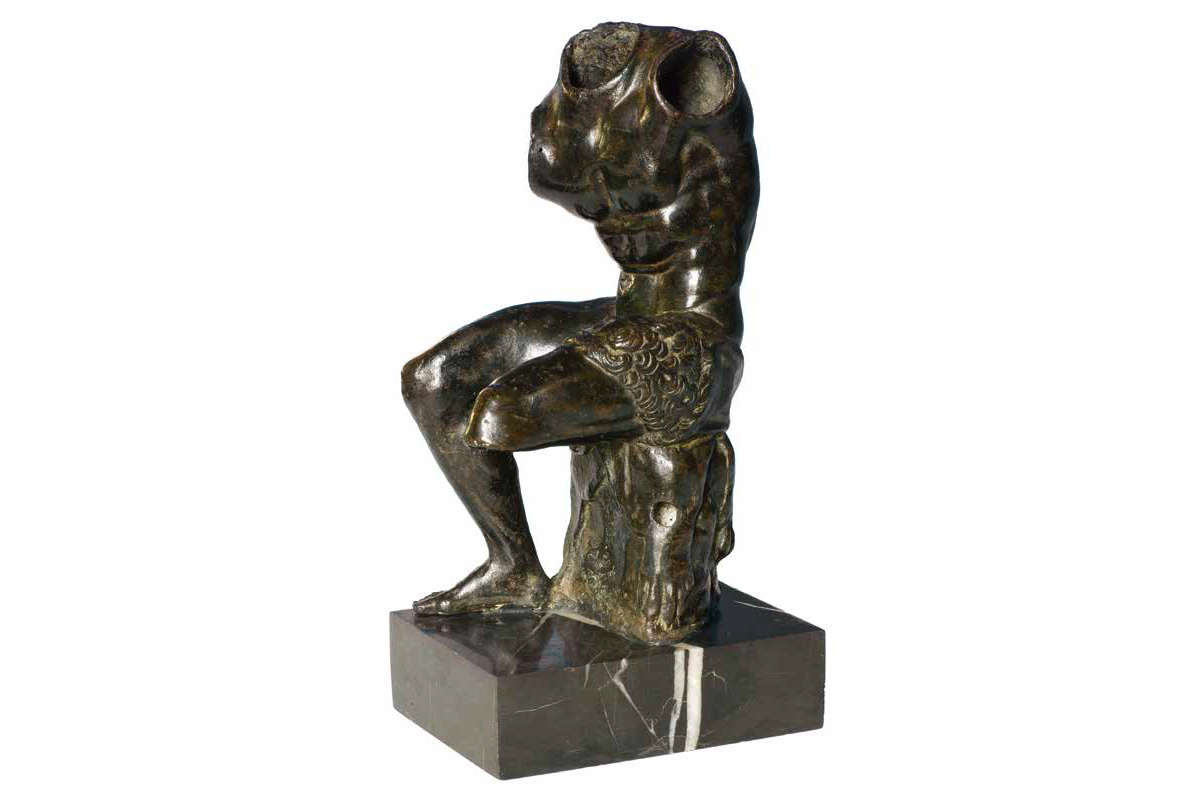

The clarity of the Fabrica plates allowed the complexity and wonder of the human body to be appreciated. In this way, Vesalius succeeded in creating a bridge between science and art, between aesthetics and specialized knowledge. Particular are the plates illustrating the male torso and the female torso: the female one, in particular, finds a singular artistic reference, since it reproduces an ancient sculpture, perhaps the Torsetto that figured in the collection of Marco Mantova Benavides, a jurist who, like Vesalius, taught at the University of Padua: the anatomical table of the dissected torso seems to echo one of these statues, yet showing us the internal organs with extreme precision. Similarly, the male one cannot in turn fail to recall the very famous Belvedere Torso. According to scholar Carlotta Moro, Vesalio was a regular participant in Padua’s intellectual cenacles, to which figures such as Benedetto Varchi, Sperone Speroni, Daniele Barbaro, and Giulio Camillo were linked, and thanks to which the doctor could evidently deepen his interest in art.

![Andrea Vesalius, De humani corporis fabrica libri septem, Basel, John Oporino (1543; printed book with woodcuts [12], 659 [i.e. 663, 37] p.; [1] c. of fold-out table: ill., 1 retr.; 2nd; Vicenza, Biblioteca Civica Bertoliana, BE-156729) Andrea Vesalius, De humani corporis fabrica libri septem, Basel, John Oporino (1543; printed book with woodcuts [12], 659 [i.e. 663, 37] p.; [1] c. of fold-out table: ill., 1 retr.; 2nd; Vicenza, Biblioteca Civica Bertoliana, BE-156729)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2025/3038/andrea-vesalio-frontespizio-fabrica.jpg)

![Andrea Vesalius, Anatomical Table with Dissected Male Torso, from De humani corporis fabrica libri septem, Basel, Giovanni Oporino (1555; printed book with woodcuts, 1555 [12], 824, [48] p., [2] c. of fold-out table: ill., 1 retr.; Imprint: uri s.s., Cam dest (3) 1555 (R). 2º; Padua, University Library, inv. B.67.b.16, p. 575) Andrea Vesalius, Anatomical Table with Dissected Male Torso, from De humani corporis fabrica libri septem, Basel, Giovanni Oporino (1555; printed book with woodcuts, 1555 [12], 824, [48] p., [2] c. of fold-out table: ill., 1 retr.; Imprint: uri s.s., Cam dest (3) 1555 (R). 2º; Padua, University Library, inv. B.67.b.16, p. 575)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2025/3038/andrea-vesalio-torso-femminile.jpg)

![Andrea Vesalius, Anatomical table with dissected female torso, from De humani corporis fabrica libri septem, Basel, Giovanni Oporino (1555; printed book with woodcuts [12], 824, [48] p., [2] c. of fold-out table: ill., 1 retr.; in-folio; London, The Wellcome Collection, Library, inv. EPB/D/6562/2) Andrea Vesalius, Anatomical table with dissected female torso, from De humani corporis fabrica libri septem, Basel, Giovanni Oporino (1555; printed book with woodcuts [12], 824, [48] p., [2] c. of fold-out table: ill., 1 retr.; in-folio; London, The Wellcome Collection, Library, inv. EPB/D/6562/2)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2025/3038/andrea-vesalio-torso-maschile.jpg)

In the Renaissance, even before Vesalius, the anatomical approach had become much more sophisticated, with the integration of graphic representations alongside scientific research. “The tension toward the naturalistic depiction of the human body and the consequent need to take possession of anatomical knowledge in order to convincingly render a body in motion,” writes Davide Gasparotto in the exhibition catalog Modern Bodies, "informed the most important fifteenth-century treatises on the arts. As early as the late fourteenth century, Cennino Cennini in his Book of Art states that ’the most perfect guide that can have and best rudder is the triumphal door of portraying de naturale.’ In De statua (1450-1464), Leon Battista Alberti suggests a complex system of measurement to achieve a coherent depiction of the human body, warning - in the wake of Vitruvius - that the statuary must have observed and understood the structure and proportions of each member of the body, the relationship between the individual members and of these to the whole, but also insisting that ’it will also greatly benefit the statuary not to ignore the number of bones and the protrusions of muscles and tendons.’"

One of the first artists to depict anatomy in a very rigorous way was Antonio del Pollaiolo (Florence, c. 1431 - 1498): although his main interest was sculpture, Pollaiolo exerted a fundamental influence on the depiction of the human body, thanks to his careful observation of its anatomical structure. Pollaiolo is famous for seeking an in-depth understanding of musculature and bone to improve his ability to depict the human figure in motion (we see this, for example, in one of his most famous sculptures, theHercules and Antheus): Antonio del Pollaiolo, Vasari wrote in a page from which the supremacy of the Florentine artist is deduced with great clarity, “s’intese degli ignudi più modernamente che fatto non avevano gli altri maestri inanzi a davanti a lui, e scorticò molti uomini per vedere la notomia lor sotto; e fu primo a mostrare il modo di cercar i muscoli, che avevano forma e ordine nelle figure.”

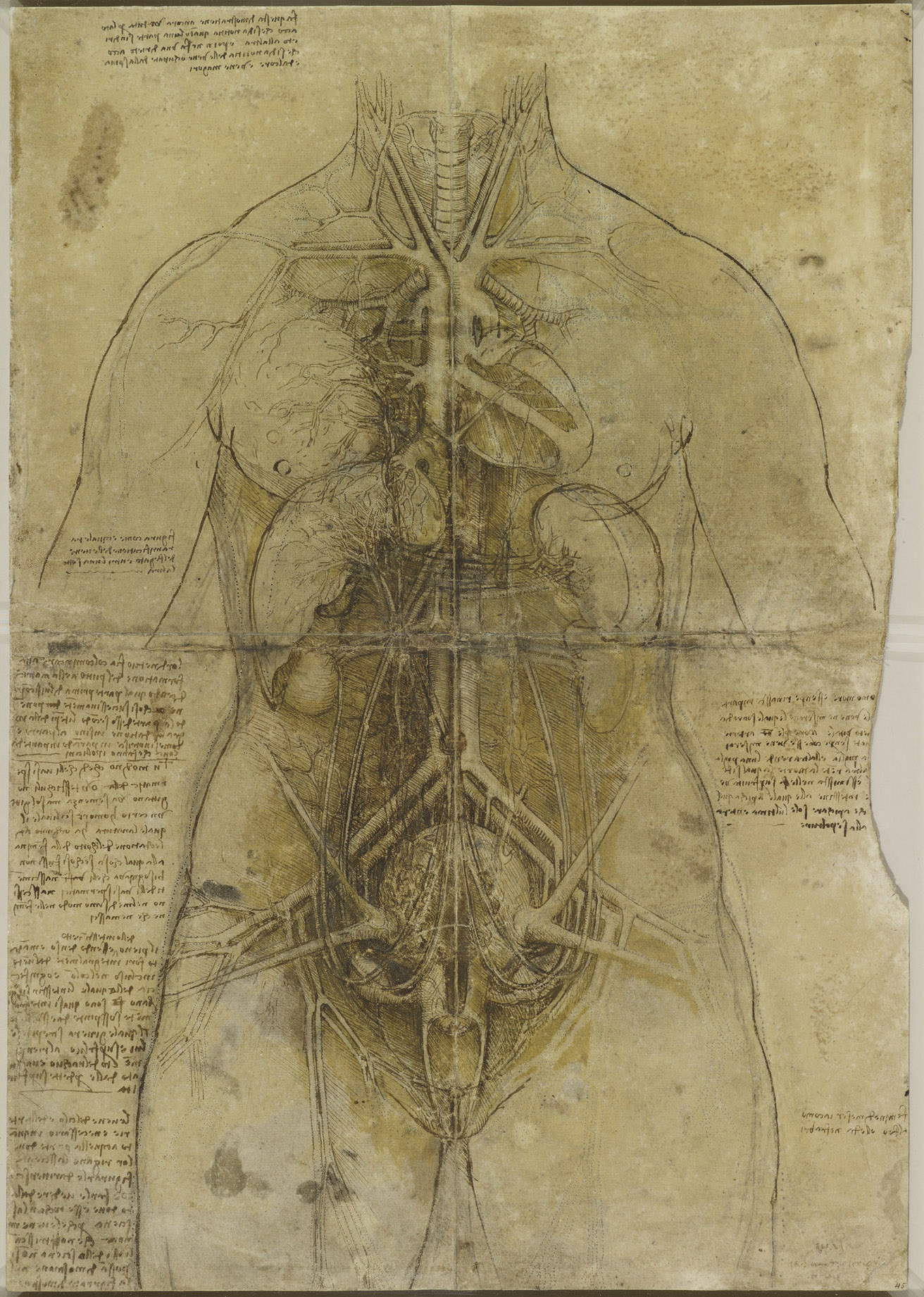

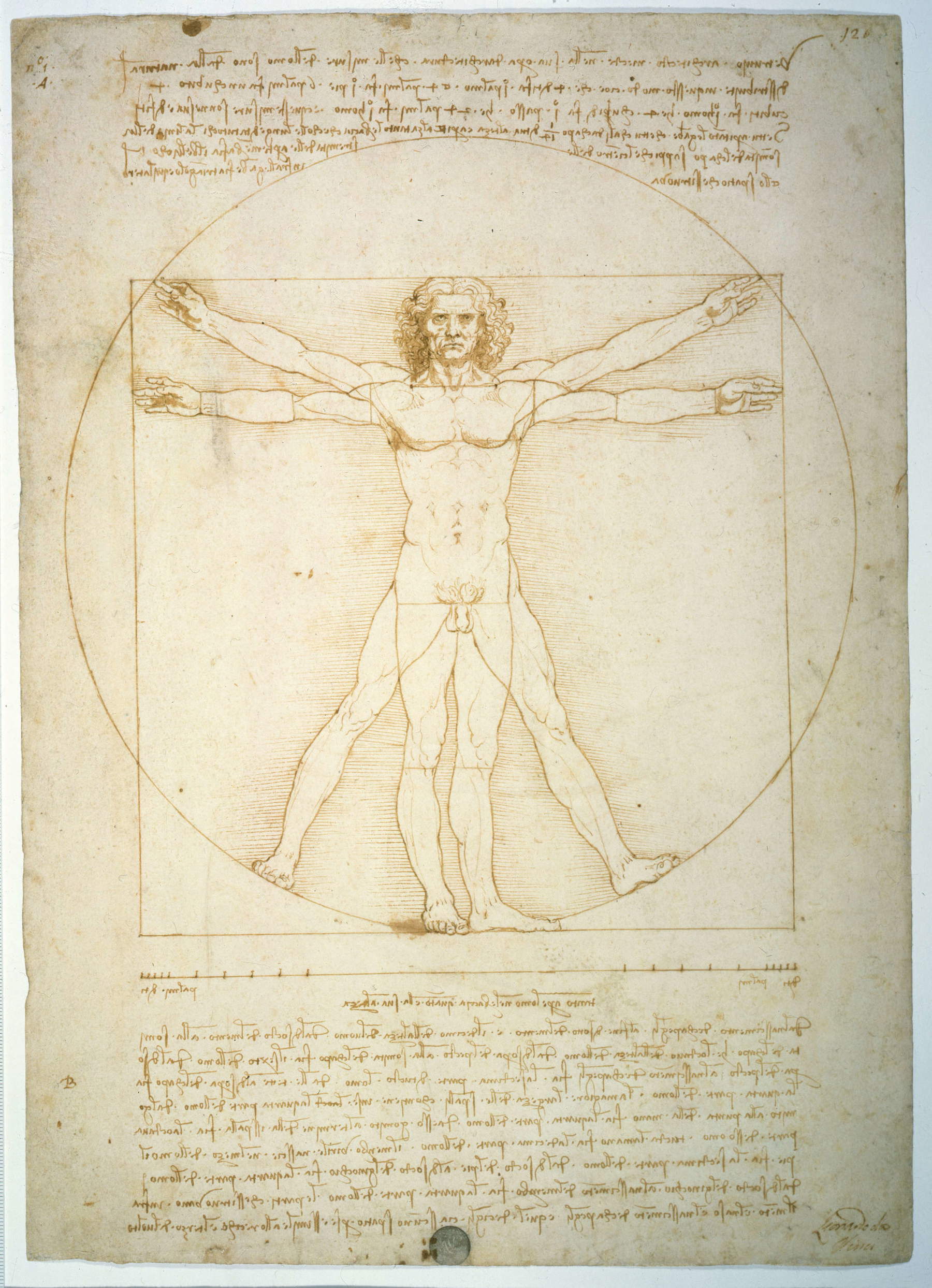

However, it is undoubtedly Leonardo da Vinci who is one of the most emblematic figures in the field of artistic anatomy. His passion for studying the human body is well documented, with dozens of anatomical drawings ranging from muscles and bones to internal organs. Leonardo did not just observe the human body, but also engaged in dissection, as seen, producing drawings of extraordinary precision. His scientific methodology and attention to detail marked a fundamental step in the development of anatomical knowledge. In particular, Leonardo studied in detail the muscular system, heart, blood vessels, internal organs, and nervous system, attempting to represent them three-dimensionally. His drawings, including those of the heart and blood vessels, are among the most accurate ever made before Vesalius’ Fabrica. His famous annotation that drawing is essential to “grasping” the nature of the human body ties him directly to the anatomical tradition, demonstrating how artistic practice was fundamental to scientific progress. Even theVitruvian Man was born, writes Adriana Cavarero, “on the basis of numerous empirical measurements conducted by the artist on the bodies of young flesh-and-blood men,” since “behind the ideal, geometrically perfect body is the empirical body, investigated and measured in its concreteness and natural variability.”

Leonardo also profoundly influenced Andrea Vesalius. Although the Flemish physician did not have direct access to Leonardo’s anatomical drawings, his work fits into the groove traced by the artist, with the idea that dissection was the way to overcome the dogmas of the ancient texts and arrive at a direct and precise understanding of the human body: attesting to this precedence of Leonardo over Vesalius is also a 16th-century Pavia physician, Girolamo Cardano, who in a passage of his treatise De subtilitate considers Vesalius’ work to be a kind of continuation of that of Leonardo da Vinci.

Among Leonardo da Vinci’s most exemplary studies is the aforementioned Great Lady preserved at the Royal Collection in Windsor: it is an anatomical study of a female body that received this nickname in 1972 from Martin Kemp, one of Leonardo da Vinci’s most distinguished scholars (Carmen Bambach, on the other hand, renamed the sheet Atlas of Female Anatomy in 2019). The work, writes Carlotta Moro, “marks the culmination of Leonardo’s anatomical research and depicts the complex configuration of the cardiovascular, respiratory, and uro-genital systems of the female body and their mutual relationship [...] The result is a visual transposition of the ’cosmography of the lesser world,’ in which the body is not a closed entity, but part of a dynamic network in relation to the laws of nature. Thanks to a delicate play of transparencies and superimpositions, Leonardo succeeds in restoring on the sheet the depth of the body and the functional hierarchy of the organs: the heart is simplified in its essential form, while the uterus, enlarged with respect to its real proportions and idealized in a perfect spherical shape, occupies a large part of the abdominal cavity.” Leonardo da Vinci, moreover, also made use of the consultation of treatises such as Johannes de Ketham’s Fasciculo de medicina , published in Venice in 1491 by the printing house of the brothers Giovanni and Gregorio de Gregori: however, the Tuscan artist surpassed the illustrations in this work precisely because of thedirect observation that was the result of his dissections.

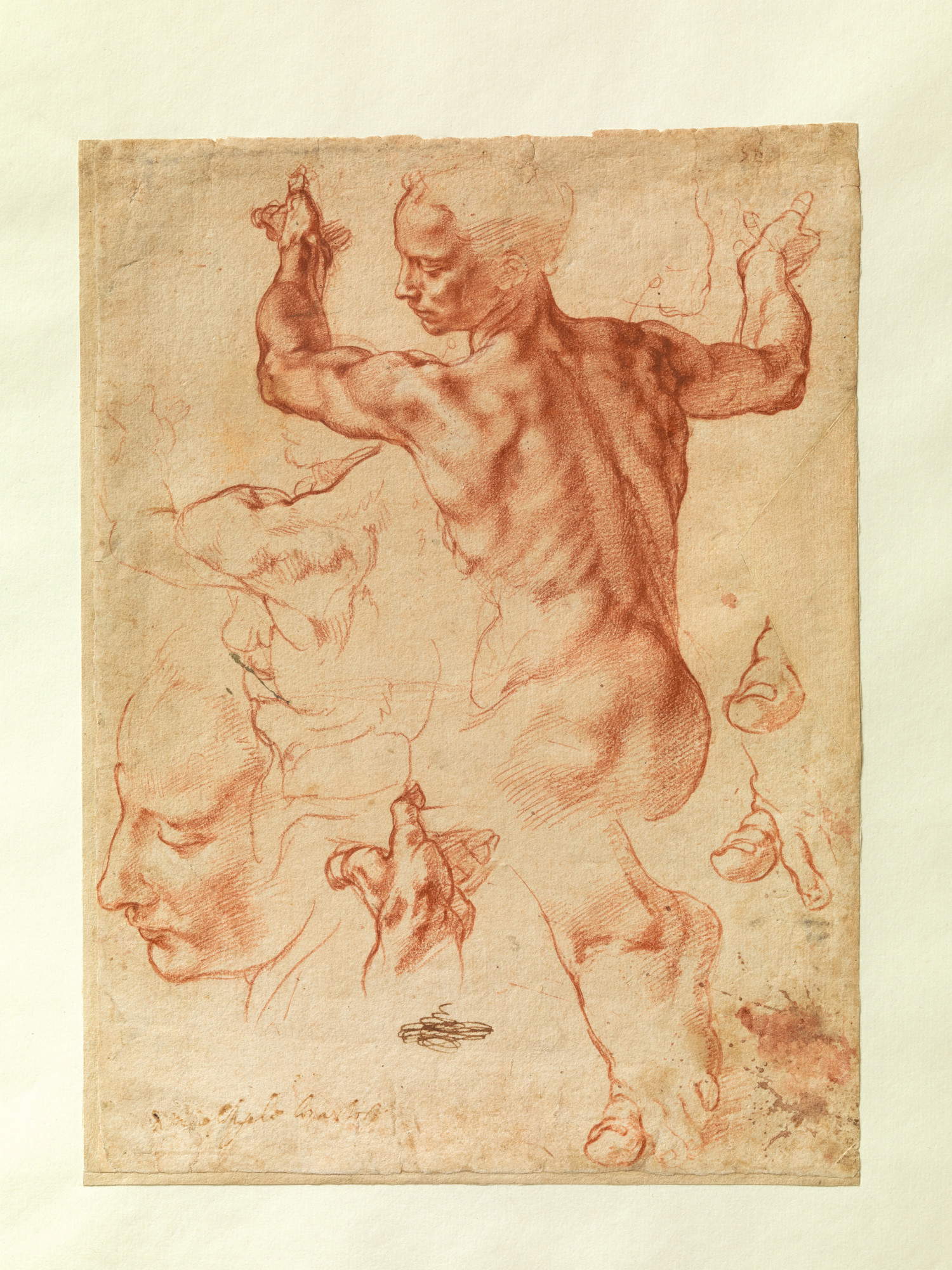

Michelangelo Buonarroti (Caprese, 1475 - Rome, 1564), although not a professional anatomist, also contributed significantly to the understanding of the human body. His relentless pursuit of perfection in representing the human body led him to study muscles, bones and joints with an intensity that made him one of the great masters of anatomical representation. His figures are famous for the extraordinary accuracy with which Michelangelo depicts muscles and bones: moreover, like Leonardo, Michelangelo was also involved in projects related to anatomy. Indeed, according to Davide Gasparotto, some Michelangelo sheets suggest that the artist was thinking of reproducing some of his anatomical studies in print: his collaboration with the physician Realdo Colombo (Cremona, 1516 - Rome, 1559) for an anatomical treatise could have led to a further development of anatomical illustrations precisely because of Michelangelo’s drawings, but in the end, Colombo published his De re anatomica without any illustrations in 1559. Leonardo da Vinci, on the other hand, had collaborated with the physician Marcantonio Della Torre (Verona, 1481 - Riva del Garda, 1511) with a view to publishing a book on anatomy, but again the affair had no conclusion.

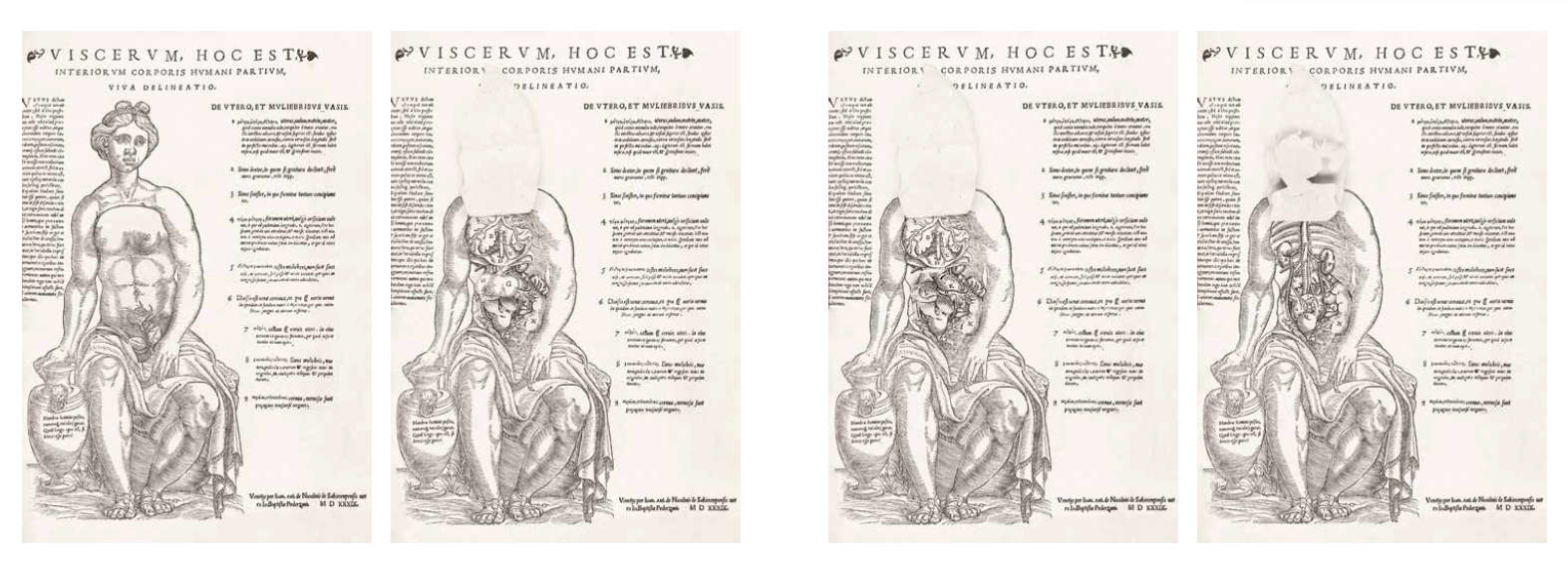

Within this framework, a certain importance was also assumed by anatomical prints with superimposed movable flaps, which were introduced in Germany and neighboring areas in 1538, thus shortly before the publication of Vesalius’ treatise. The earliest were due to the work of two artists, Heinrich Vogtherr (Dillingen an der Donau, 1490 - Vienna, 1556) and Jost de Negker (Antwerp, 1485 - 1544), active in Strasbourg and Augsburg, respectively. It was from these that Vesalius himself drew important insights for the illustrations in Fabrica: in addition to the treatise, an Epitome was also published in 1543 with figures that could be cut and mounted for teaching purposes. In Italy, the only examples of anatomical prints with movable flaps are the plates known as Viscerum, hoc est interiorum corporis humani partium , which analyze male and female anatomy and were published in 1539 by printer Giovanni Antonio Nicolini da Sabbio at the request of bookseller Giovanni Battista Pederzani. The female table, in particular, had seven flaps, seven flaps, colored by hand, that could be lifted: when the flaps were closed, a female figure could be seen, while when the flaps were opened, the internal organs were revealed. Vesalius’ treatise would come soon after.

![Johannes de Ketham, Fas[c]iculo de medicina, Venice, Giovanni and Gregorio de Gregori (1494; printed book with watercolor woodcuts 52 c., in-folio; Padua, Center for the History of the University of Padua, CSU.S.A.146) Johannes de Ketham, Fas[c]iculo de medicina, Venice, Giovanni and Gregorio de Gregori (1494; printed book with watercolor woodcuts 52 c., in-folio; Padua, Center for the History of the University of Padua, CSU.S.A.146)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2025/3038/johannes-de-ketham-fasciculo.jpg)

The practice of dissecting corpses for medical purposes is first documented in the 13th century (except, of course, for the dissections that took place in antiquity, however, not in the territories dominated by Rome, which prevented the practice: dissections are attested in Greece and Egypt), and specifically, the first record dates from 1286: that year, reports the Parma chronicler Salimbene de Adam (Parma, 1221 - San Polo d’Enza, 1288) in his Cronica, a doctor from Cremona had the body of a dead man “opened” (so in the Latin text of the chronicle) as part of an investigation into an epidemic. In contrast, the first autopsy of which we know the details, including the name of the victim, dates from 1289: it happened in Bologna, and two doctors were commissioned to examine the body of one Iacopo Rustighelli to ascertain the cause of his disappearance. The chronicles of the time then report, from this time on, several other autopsies always on the side of forensic investigations.

Also around the same time are the first dissections for teaching purposes, performed in university settings. We do not know, however, whether the practice of pedagogical dissection preceded or followed forensic dissection, because we have roughly contemporary accounts, but without exact dates: one of the first physicians to perform didactic dissections was the Florentine Taddeo Alderotti (Florence, 1215 - Bologna, 1295), who taught at the University of Bologna from 1260. One of his disciples at the Bolognese athenaeum was Mondino de’ Luzzi himself, and, as we have seen, the first irrefutable evidence of a dissection in an academic setting is precisely that described in the Anathomia Mundini of 1316. In particular, Mondino mentions one performed in January 1314; moreover, he claims to have conducted one himself in March of the same year. From then on, the practice would spread to almost all European universities, usually resorting to the corpses of criminals who had been sentenced to death. The recourse to these subjects is explained by the morality of the time: a dissection was considered disreputable not only for the honor of the dead man who received it, but also for his family. And since for the morals of the time the respect due to executed criminals was minimal, then they could more easily be employed for dissections. More rarely, dissections were done on people who had died in an unclear manner and for whom it was necessary to clarify the causes of disappearance.

Medical schools also organized public dissections in which artists who wanted to learn more about anatomy, for example, could take part. Artists could not conduct dissections on their own: the practice was obviously not prohibited in general, but could only be conducted in medical or academic settings. As for Leonardo da Vinci, for example, we do not know for sure when he began to do the dissections he claims to have performed, but Vasari, for example, writes that he used to practice them together with Marcantonio Della Torre, although it is assumed that Leonardo began to engage in dissections even before he met the Veronese physician. From what Leonardo himself claims, it is in fact possible to imagine that the artist had conducted some dissections in the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova in Florence: in his papers for example there is a detailed account of the dissection of an elderly man, datable to 1508, which took place precisely on the hospital premises. It is from this period, however, between 1505 and 1510, that Leonardo’s drawings begin to be based on direct observation.

As for Michelangelo, we know from Vasari that he must have begun probably even earlier than Leonardo (although Michelangelo was twenty-three years younger) to practice dissections: in fact, the historiographer relates that, by virtue of his friendship with the prior of the convent of Santo Spirito, in some rooms of the hospital attached to the convent that the prior himself put at his disposal, Michelangelo, “many times flaying dead bodies, in order to study the things of notomia, began to give perfection to the great design which he then had.” Michelangelo is presumed to have attended to this practice roughly between 1492 and 1498.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.