It may be hard to believe today, but the Olympic Games, for seven editions, also hosted art competitions. One finds it hard to believe, because we are always used to thinking of art and sports as two totally separate fields, perhaps even incapable of communicating with each other. One finds it hard to believe, because in the society of hyperspecialization one cannot even imagine such a seemingly strange, dissonant, unexpected contamination. And those who learn about it usually express surprise, astonishment: often not even the most ardent sports fans, those who could quote from memory all the podiums of men’s epee or bicycle racing from Athens 1896 to the present, remember that, for several editions of the Games, art and sports were part of the same competition program. Thus, there existed a time in history when painters, sculptors, architects, men of letters, and musicians participated in the Olympics on a par with runners, fencers, swimmers, boxers, wrestlers, and gymnasts. They too represented their nations. They too competed to win the gold medal. They too are now registered in the huge database of the Olympic Games website, just like the athletes.

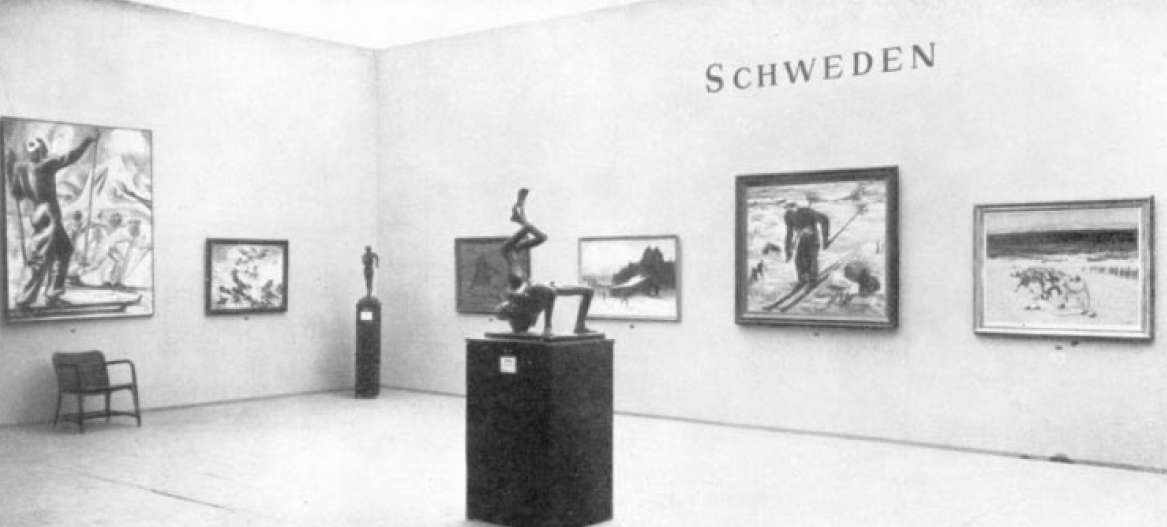

Art competitions first entered the Olympic program in 1912, at the Stockholm Games, and remained there for seven consecutive editions, until the 1948 London Olympics. It was Italy, moreover, that prevailed in the first edition, winning two gold medals (music and painting) and hoisting itself to first place in the discipline’s medal table, ahead of France, the United States and Switzerland. The idea of including a program of artistic competitions within the Olympic Games came from Baron Pierre de Coubertin himself, who as is known was among the founders of the modern Olympics, and who had always nurtured a desire to combine art with sports. “The time has come to set a new stage,” he wrote in 1904 in an article published in Le Figaro, “and to restore the Olympiad to its original beauty. In the days of the splendor of Olympia, letters and the arts, harmoniously combined with sport, ensured the greatness of the Olympic Games. It must be the same in the future.” In 1906, De Coubertin therefore convened a meeting of the IOC, the International Olympic Committee that had been founded in 1894, in Paris to discuss the possibility of having artists participate alongside the athletes by including in the Games a program of five art competitions: architecture, literature, music, painting and sculpture. The art competitions were to be included as early as the 1908 London Olympics, but organizational problems forced the IOC to postpone the debut of the art competitions to the 1912 Stockholm Games. Thus it was in Sweden that art competitions were held for the first time.

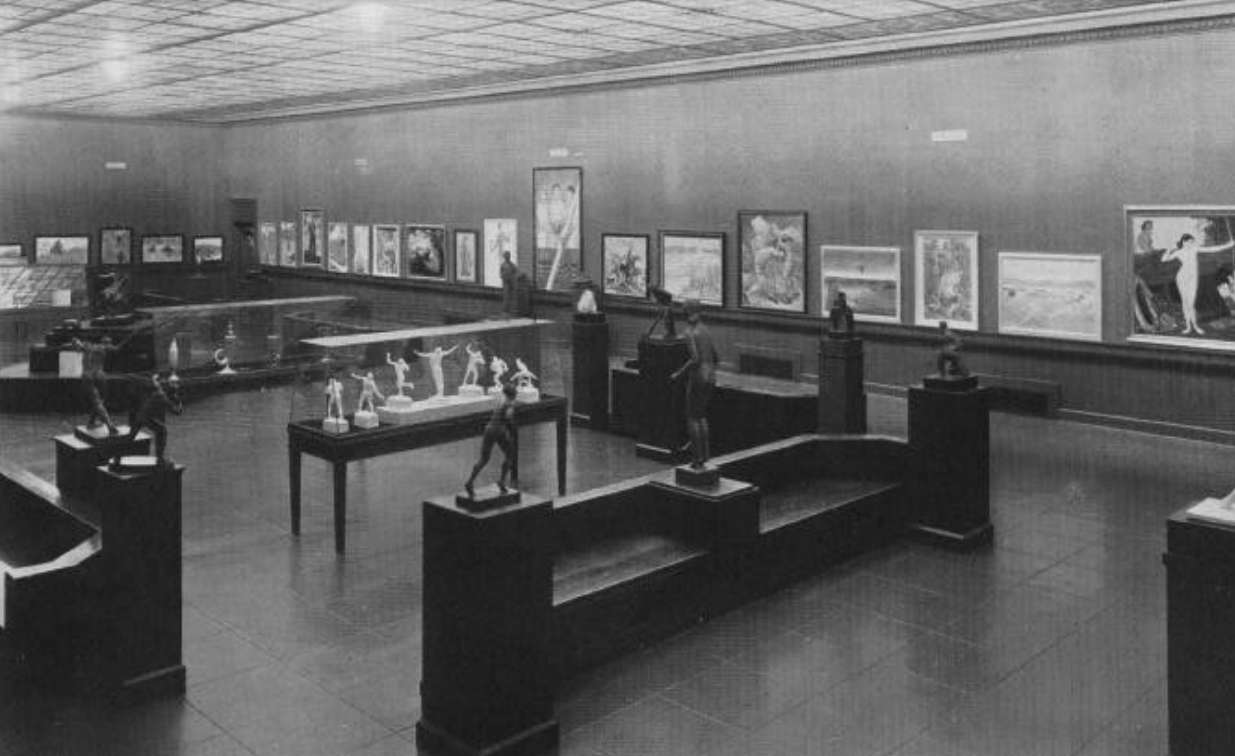

“The Fifth Olympiad,” reads the official report of that edition of the games, “will include competitions in architecture, sculpture, painting, music and literature. The jury may consider only subjects that have not been previously published, exhibited or performed, and that have some direct connection with sports. The winner of each of the five competitions will be awarded the Olympic gold medal. Selected works, as far as possible, will be published, exhibited or performed during the 1912 Olympic Games. Contestants must notify their intention to enter one or more competitions on January 15, 1912, and the works must be in the hands of the jury before March 1, 1912. There are no limits on the size of manuscripts, plans, drawings or canvases, but sculptors are required to send clay models not exceeding 80 centimeters in height, length or width.” We do not have to imagine art competitions in the sporting sense of the term: participants did not compete at the same time at an agreed place, but were required to send in their work before the Olympics began, after which an exhibition would open in which the works would be displayed, and a jury would finally evaluate the pieces and award medals.

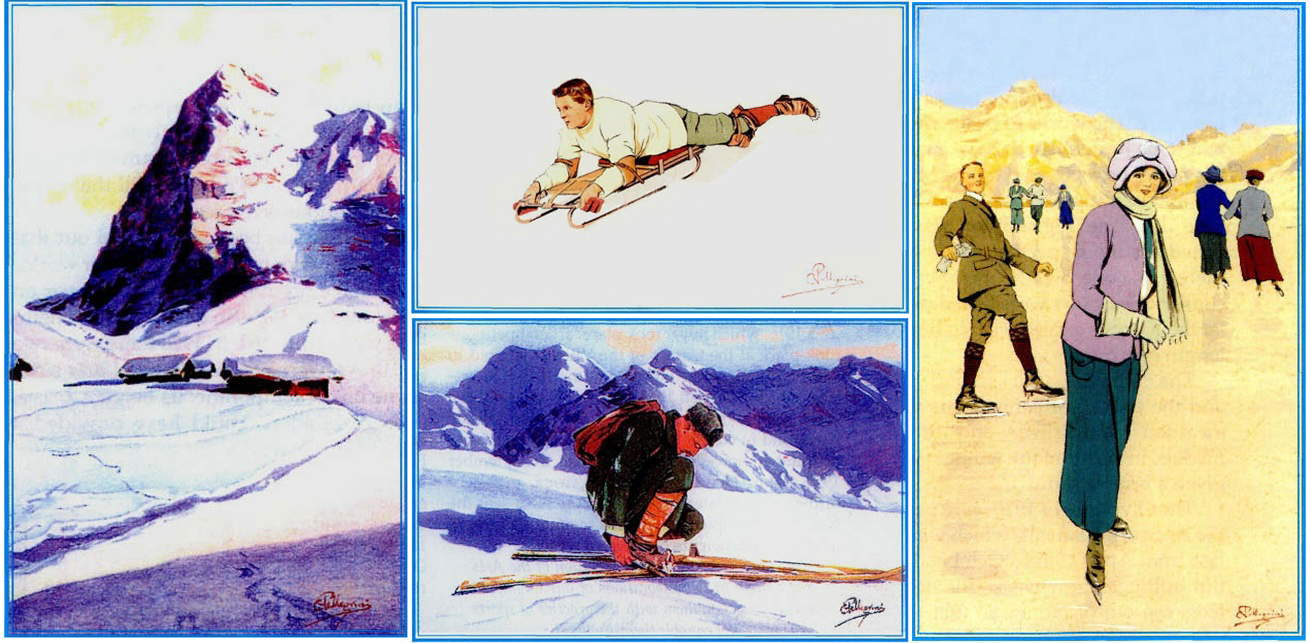

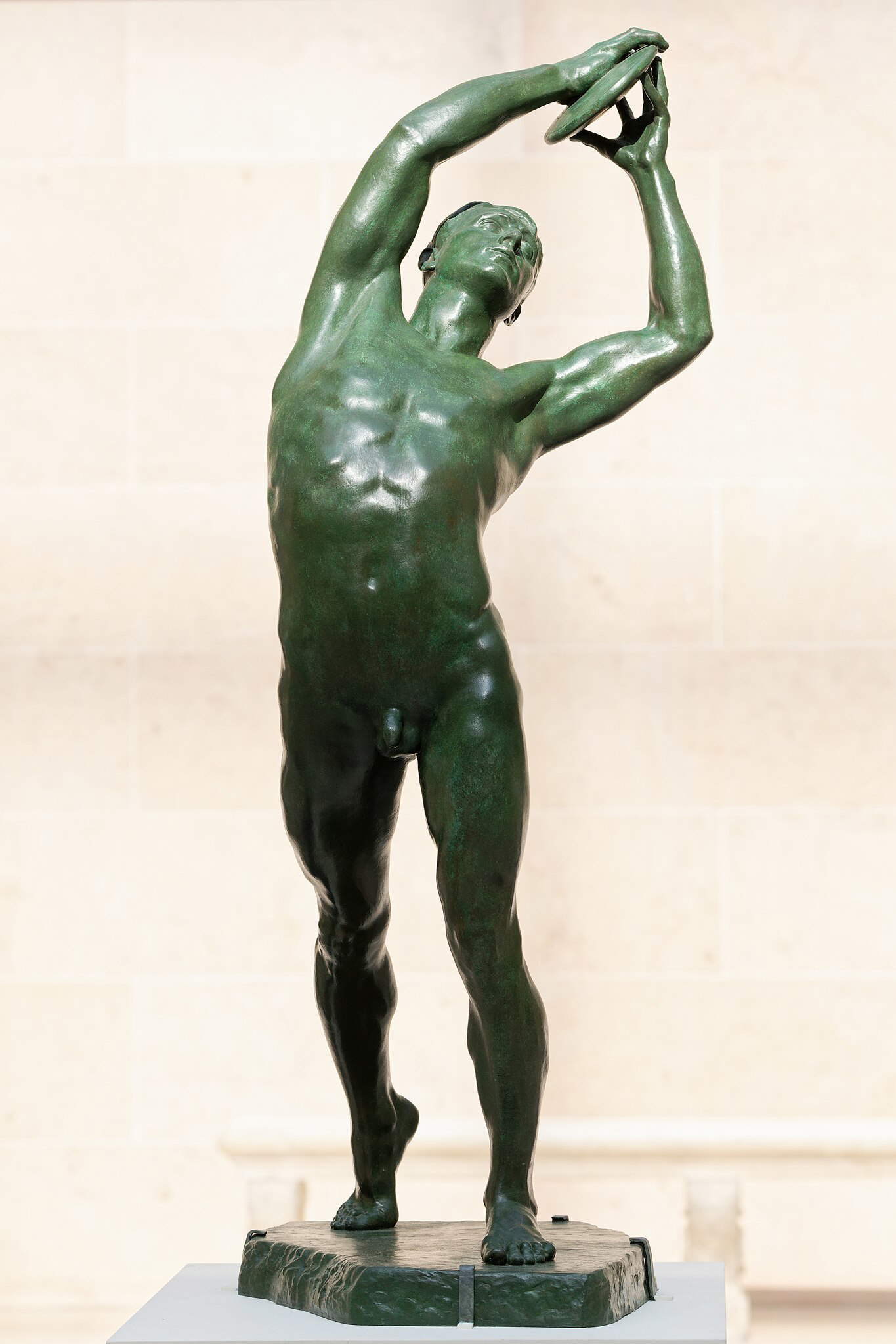

The designs submitted by competitors, as noted in the 1912 Games report, had to do with sports in some way. At the first edition of the art competitions, the architecture competition was won by the Swiss Eugène-Édouard Monod and Alphonse Laverrière (the latter was the one who designed the Lausanne train station) with a construction plan for a stadium. In literature, Pierre de Coubertin himself won, with anOde to Sport, but he entered a double pseudonym “Georges Hohrod & Martin Eschbach,” and took the satisfaction of even beating Gabriele d’Annunzio, who was also in the race. For music, the gold medal went to Italian Riccardo Barthelemy, who won with an Olympic Triumphal March. The gold medal for painting went to another of our compatriots, Carlo Pellegrini, who presented three friezes dedicated to winter sports. And the sculpture competition was won by American Walter Winans for his bronze An American trotter. Interestingly, Winans had also managed to win a medal in sports competitions in the same Olympiad, since he won a silver in shooting (while four years earlier, in London 1908, he had won the gold medal). He was one of only two performers to achieve the feat: the other was Hungary’s Alfred Hajós, gold in the 100 and 1200 freestyle swimming in Athens 1896, and silver in architecture in Paris 1924. Winans was, however, the only one to win a medal in art and one in sports in the same edition of the Games.

The division among five disciplines went on until the 1924 Paris Olympics: it was the games of Luxembourg painter Jean Jacoby, a name unknown to most today, but he was the most medaled artist ever, having won gold at both the Paris 1924 Games (beating Irish expressionist Jack Butler Yeats, brother of the William who had won the Nobel Prize for literature the year before) and the Amsterdam 1928 Games. The gold for architecture was not awarded (if the jury felt that the criteria for awarding the most coveted prize were not there, it could refuse to award an artist the gold, and could instead directly award thesilver), and even in the music competition no one was considered worthy of receiving a medal (“the jury,” reads the laconic verdict in the official report, “did not establish any award”). It was not a happy edition for Italy: we did not win any medals, also because we participated with only three artists. Yet among those three was one of the heavyweights of Italian art at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Vincenzo Gemito, who was now in his seventies at the end of his career, and participated with no less than seven works, including his very famous Acquaiolo, but none of them earned him a medal: the sculpture podium consisted of Greece’s Kostantinos Dimitriadis, Luxembourg’s Frantz Heldenstein, and two equal bronze medalists, France’s Claude-Léon Mascaux and Denmark’s Jean-René Gauguin. Yes, Jean-René was the son of the better-known Paul Gauguin, the fourth fathered by his Danish wife Mette Sophie Gad; he was forty-three years old at the time, had taken his mother’s citizenship, and was also an artist like his father, although he had taken up sculpture: he won the bronze with a massive Boxeur. It was possible to participate with more than one work, with the consequence that there were those who obtained two medals in the same competition, a situation that is impossible in sports: this was the case of the Swiss Alex Diggelmann, who won a gold in advertising graphics at the 1936 Games, and especially a silver and a bronze in the “applied arts” category (heir to advertising graphics) at London 1948.

At the 1928 Olympics, the five categories had their respective specialties: architecture awarded medals for architectural design and urban planning; literature competed in the disciplines of poetry, dramatic works and epic; music had the competitions of song, instrumental composition and composition for orchestra; painting was divided into painting proper, drawing and graphic design; and sculpture awarded medals in the categories of “statuary” and “reliefs and medallions.” Italy won only one silver (Lauro de Bosis in the dramatic works category: moreover, he was the only medalist in his discipline, because gold and bronze were not awarded). The case of music was curious: of three specialties, only one medal was awarded, bronze in composition for orchestra, won by Rudolph Simonsen of Denmark. Among the well-known names who participated in that edition of the Games, those of Franz von Stuck, George Grosz and Erich Heckel (both competing in painting), Max Liebermann (competed in graphic design), and that of Carlo Fontana from Carrara, who appeared in the sculpture competition with a very famous work, the design for the Quadriga of the Vittoriano, installed on top of the very monument in 1928, should be remembered. Also present was German sculptor Arno Breker, who went down in history primarily for his works celebrating the Nazi regime. And there was another artist who participated in the painting competitions after a background as an athlete: the British Edgar Seligman, winner of two silver medals in the men’s team epee (in London 1908 and Stockholm 1912). The next Games in 1932 saw the reinstatement of the single competition for literature and music (a discipline that continued to have no winner). Among the big names who participated in that edition, scrolling through the list of participants one comes across Walter Gropius, futurist Gerardo Dottori, fauve Kees van Dongen, and Dutch impressionist Isaac Israëls. Also participating was the American artist John Russell Pope, who was responsible for the building that houses the National Gallery in Washington: he won the silver medal in architectural design.

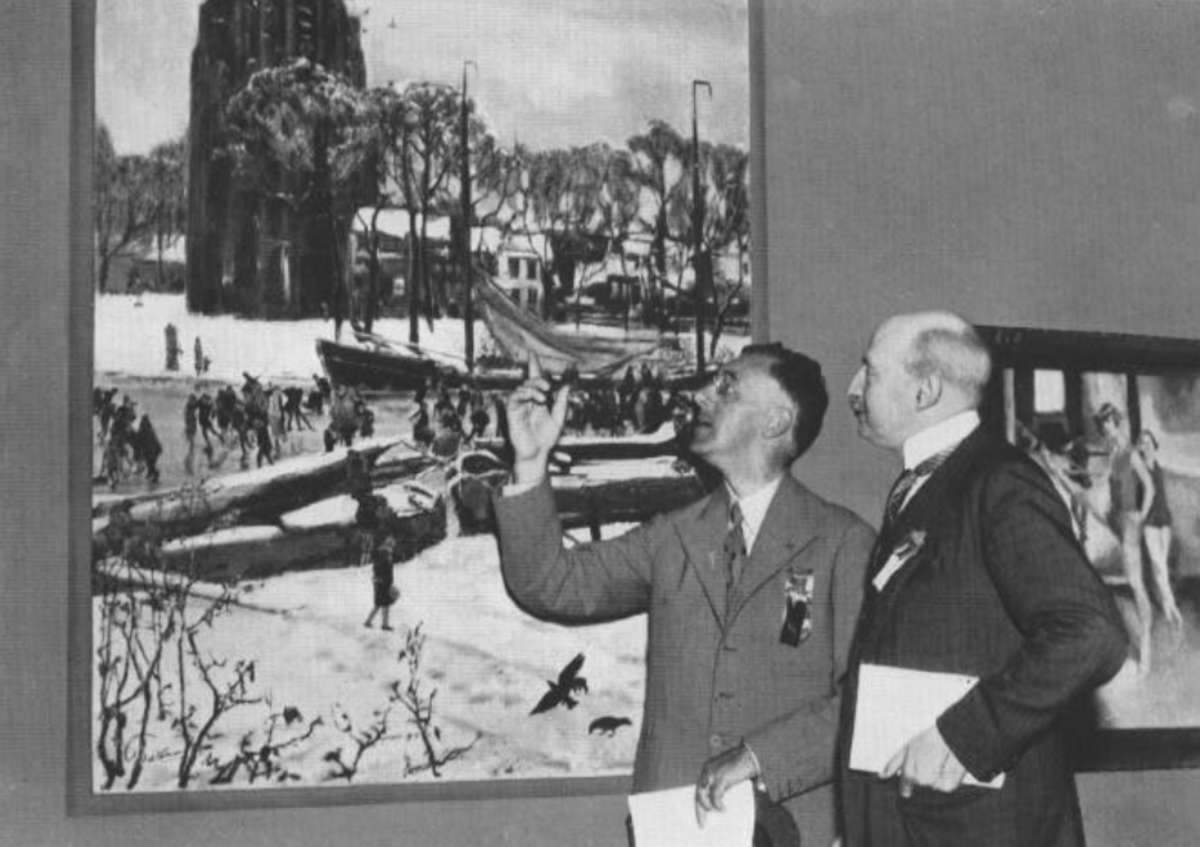

With the 1936 Berlin Games there was a return to the disciplines of the edition of eight years earlier, and in addition a new specialty, commercial graphics, was introduced, while medallistics and relief were separated. The Olympics organized under the Nazi regime saw, as one would naturally expect, the triumph of German athletes, who took home twelve of the thirty-two medals awarded, winning five golds out of nine. Regime sculptor Arno Breker took silver in statuary, surpassed only by 29-year-old Italian Farpi Vignoli. The Italian contingent at the German Olympics was decidedly large, and a number of famous names can be found among the participants: an early-career Pier Luigi Nervi who took part in the architectural design competition, the Giulio Arata who designed the Ricci Oddi Gallery in Piacenza and the Bologna Stadium, sculptors Publio Morbiducci, Francesco Messina, Aldo Buttini and Romano Romanelli, and a large Futurist cohort consisting of Enrico Prampolini, again Gerardo Dottori, Tullio Crali, Thayaht.

The 1948 London Games (attended by, among others, Mino Maccari, Giuseppe Capogrossi, Marino Mazzacurati, and even the great poet Giorgio Caproni) were the last to count art competitions in the official program: it was during an IOC meeting in 1949, in Rome, that it was decided to turn the art competitions into art exhibitions, without prizes or medals for the participants. The cause that led the International Olympic Committee to make this decision lay in the status of the participants: at that time, only amateur athletes were allowed to participate in sports competitions (with some exceptions, such as fencing masters: even though the latter drew their livelihood from their sporting activities, they were still accepted to competitions), while art competitions were also open to professionals. It therefore appeared “illogical,” as the minutes of that meeting put it, that professionals were able to “compete in these exhibitions and be awarded Olympic medals.” The orientation imposed by the then vice-president of the IOC, the American Avery Brundage (who later became president in 1952), a staunch defender of amateurism, had a considerable influence on the choice: he had fought hard for art to be excluded from the competitions after London 1948, believing that artistic competitions represented an inappropriate showcase reserved for professionals in a major event intended for amateurs. From these reasons came the resolution to no longer consider artists on a par with athletes. No more competitions and medals for painters, sculptors, musicians, and men of letters. The debate over “amateurism versus professionalism” would hold sway for decades, with various arguments: trivializing, it could be simply recalled that, on the one hand, supporters of amateurism wanted to prevent athletes from participating out of self-interest and that forms of business revolved around the event, which Pierre de Coubertin disliked and had always opposed, while supporters of professionalism believed that opening the competitions only to amateurs excluded the strongest athletes and in particular those who did not have a standard of living that would allow them to train without earning from their sporting activity. A long-standing issue: only the 1988 Seoul Olympic Games were opened, for the first time in history, to professionals in all disciplines.

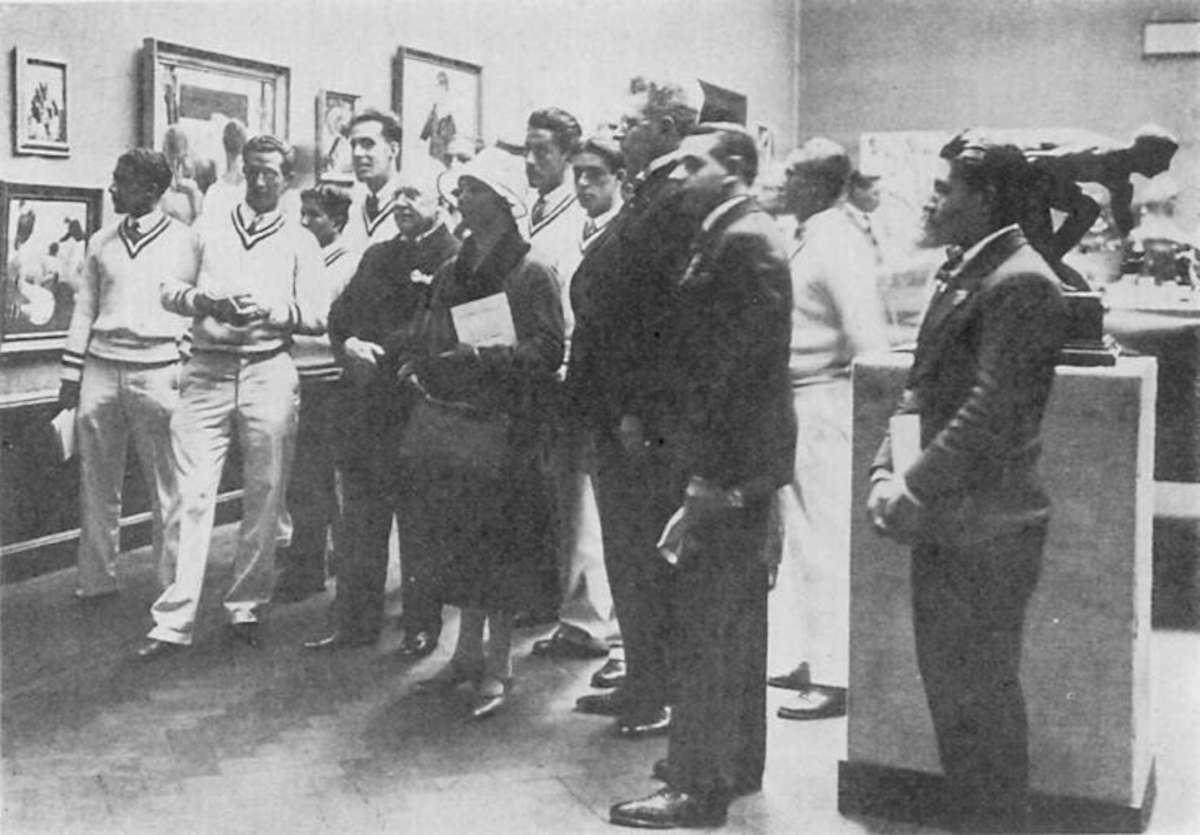

Looking at the lists of medalists, the names of the many participants, looking at their works, perhaps one can guess why, contrary to what one might think, the art competitions were not very successful among the artists of the time. Very few greats took part in the Olympic Games, compared with hundreds of mediocre artists, amateurs forgotten by history, and this despite the fact that the organizing committees fought to bring the most recognized and celebrated artists to the competitions. Many did not participate because they feared that a defeat might damage their reputation. Others, on the other hand, considered them to be less than prestigious competitions because they were organized by individuals who had nothing to do with art, and this in spite of the fact that the jury lists of all editions include prominent names (a few names from the jurors of Paris 1924, for example: Pietro Canonica, Maurice Denis, Ettore Tito, John Singer Sargent, Ignacio Zuloaga, and even Gabriele D’Annunzio on the literature jury). Nonetheless, the Olympic art competitions were almost always well received by the public, with thousands of people flocking to the exhibitions to view the works of the competing artists. The success, however, was not enough to change the IOC’s mind: since the 1952 Helsinki Games, no more art competitions. And the medals so far won by the artists would later be spun off from the overall medals table of the Games, by IOC decision. As a result of this decision, Britain could no longer count on the medal awarded to the oldest Olympian, painter John Compley, who at seventy-three won silver in theengraving at London 1948 (the record valid for the official overall medal table is therefore that of Swedish shooter Oscar Swahn, who won several medals in three editions, including a team silver at Antwerp 1920 at the age of 72). The medal table for the art competitions thus remains as a stand-alone ranking, with Germany in front (precisely because of the medal haul in Berlin 1936), and then followed by Italy, France, the United States and Great Britain.

There have also been a few attempts to reintroduce art competitions at the Olympic Games, all of which have foundered: the organizers have always realized the anachronism, the paradox of a competition that equates artists with athletes. Art, however, is always present at the Olympics: there are the posters, the official sculptures, the exhibitions that accompany each edition of the Games, although artists do not compete to win the gold medal. And then, since Paris 2024, the breakdance competition has been introduced into the sports program: it’s not really like a painting competition, seeing a breakdance bout is not like visiting an exhibition, and then it’s considered sports dance, but it’s still as close to the old art competitions as one can find at the Olympic Games today. In the improbability of a return of painters, sculptors and literati among the medalists, art enthusiasts have enough to content themselves with. And that’s just fine.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.