When art in the Renaissance was also political propaganda: Garofalo's masterpiece

It is an episode in the history of the Renaissance perhaps not known to many, but certainly the Battle of Polesella can be counted among the most singular ones, and not only because in the aftermath of this Ferrara military feat, events ensued that led to the birth of a masterpiece by Benvenuto Tisi known as il Gar ofalo (Garofalo di Canaro, 1481 - Ferrara, 1559), namely the Minerva and Neptune, an extraordinary painting from 1512, now in the Gemäldegalerie in Dresden (returned, however, temporarily to Italy in 2024 for the exhibition The Sixteenth Century in Ferrara. Mazzolino, Ortolano, Garofalo, Dosso, curated by Vittorio Sgarbi and Michele Danieli, at the Palazzo dei Diamanti in Ferrara until February 16, 2025: here is our review): it was also a relevant event because it helped, at least initially, to fuel the ambitions and prestige of a duke, Alfonso I d’Este (Ferrara, 1476 - 1534), who was eager to prove that he deserved the leading role in the political events of early 16th-century Italy.

The Battle of Polesella represented a great success for Ferrara militarily, showing that the duke’s army, under the right conditions, could be capable of defeating the large and well-equipped Venetian fleet, but above all it was important because it strengthened the role of the Este duchy on the Italian chessboard of the time and Ferrara’s position within the League of Cambrai, allowing the duchy to gain international relevance. However, it was a fleeting moment: the continuation of the war was not very fortunate for the duke. And it is in this context, therefore, that we need to imagine the birth of Garofalo’s masterpiece.

The Battle of Polesella

The clash between Ferrara’s land forces and the Venetian maritime armada took place on December 22, 1509 near the town of Polesella, on the Po delta, in the broader context of the League of Cambrai war that had begun theyear before, and which pitted Venice against a vast coalition that initially included the Papal States, the Empire, France, Aragon, Urbino, Mantua, Monferrato, Saluzzo and, indeed, Ferrara, united to oppose the expansionism of the Serenissima: it was, however, a conflict with fluctuating phases, with decidedly fluid deployments, in the sense that the contenders found themselves shifting with a certain ease (typical of the time, after all) from one side to the other, and even at a given moment Venice and the papacy found themselves even fighting on the same side of the front as allies in an anti-French function, following disagreements between the King of France, Louis XII, and Pope Julius II, promoter of the League. The beginning of the war was not easy for Venice: on May 14, 1509, La Serenissima suffered a heavy defeat at Agnadello and was forced to retreat from Lombardy, in late spring the French and imperials occupied almost all the major cities on the mainland beginning with Bergamo and Brescia, which were part of the Republic’s dominions, and the first signs of recovery for the Venetians came only in the fall, with the victorious siege of Padua that ended with the occupants being driven out of the city. The Battle of Polesella, however, ended the favorable moment for the Venetians and produced a stalemate that led Venice to negotiate an agreement with the pope already that same winter.

By November, in fact, the Serenissima had succeeded in retaking almost all of the Veneto occupied by the coalition, and had also managed to drive the Ferraresi out of the Polesine, which they had occupied in the early stages of the war. The Venetians, however, were not satisfied with regaining what they had lost: they had a desire to inflict on the Duchy of Ferrara a resounding and unequivocal defeat, and for this reason they sent a fleet of 17 galleys to rout the Ferraresi for good in the waters of the Po. Having arrived on the river, the Venetians built two bastions from which they intended to launch the final attack by land on the city of Ferrara once the land reinforcements arrived, which were, however, slow to arrive, as part of the army was still engaged in Venetia against the French. The Venetians, however, did not wait and continued to advance, eventually occupying the town of Comacchio on December 6. The Ferrarese, meanwhile, prepared to repel their enemies, and on December 21, commanded by Alfonso I’s brother, Cardinal Ippolito, they attacked the bastion, after which, in the night of the same day, the Ferrarese artillery was deployed along the Po, because the Ferrarese commanders, with millimetric precision and strengthened by their knowledge of the territory, had predicted a flooding of the river, which would have the effect of bringing the Venetian galleys to firing height with respect to the Este positions. The land forces of the Duchy of Ferrara then wreaked havoc on the Venetians (the Serenissima had over two thousand casualties), and the Estensi managed without difficulty to capture 15 galleys of the 17 that the Venetians had deployed. The Este victory, as mentioned, was also important for the continuation of the war, since it broke the favorable momentum of the Venetian Republic, which during the winter worked to find an agreement with the Papal States.

There is a painting that depicts the clash: it is a work by Battista Dossi (Niccolò di Battista Luteri; San Giovanni del Dosso?, before 1500 - Ferrara, 1548), executed around 1530 and now in the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Ferrara. It is a portrait of Duke Alfonso I, advanced in years, who is depicted with, in the background, precisely a scene of the Battle of Polesella. It is clear, in short, that the Este duke considered that victory the greatest military feat of his life. So much so that he wanted it eternalized behind his effigy, which was anything but common in portraiture of the time.

Garofalo’s painting

We do not know the early history of Minerva and Neptune, also known as theAllegory of Alfonso I, but it is entirely safe to assume that Alfonso I d’Este commissioned it from Garofalo shortly after the Polesella enterprise. In fact, the first known mention of the work dates back to 1618, when the painting is attested in the Ducal Palace in Modena, but there are many scholars who trace the possible commission to the celebration of the military victory. Reinforcing the hypothesis is also a curious fact: in some letters from 1512, Alfonso I is nicknamed precisely “Neptune”: the duke was thus compared to the god of the sea precisely for having inflicted a defeat on the Republic of Venice on the ground on which the Serenissima felt most secure, namely a naval battle (although it was not such in the strict sense, since the Este family fought from land). Remaining in Modena for nearly a century and a half, it ended up in Dresden in 1745 as part of the massive sale of one hundred paintings from the Este picture gallery to Augustus III of Saxony, a momentous purchase that brought a wealth of masterpieces to the German city.

In ancient times the work was attributed to Frnacesco Francia, but as early as the 19th century it was correctly assigned to Garofalo, who was still young at the time (he was 31 in 1512) and thus linked to training with Lorenzo Costa. The scene is set along a river that we can easily identify as the Po, despite the unrealistic landscape at least for Ferrara, since there are no cliffs or mountains overlooking the river in Este territory as we see in the painting. The two deities occupy the entire composition: Minerva, posed in the contrapposto pose of an ancient statue, holds a long arrow and with her left hand points to the god of the sea, Neptune, in whom it is easy to recognize the features of Alfonso I. The god is seated on a tree trunk, resting his foot on top of a dolphin and holding the trident, his typical iconographic attribute.

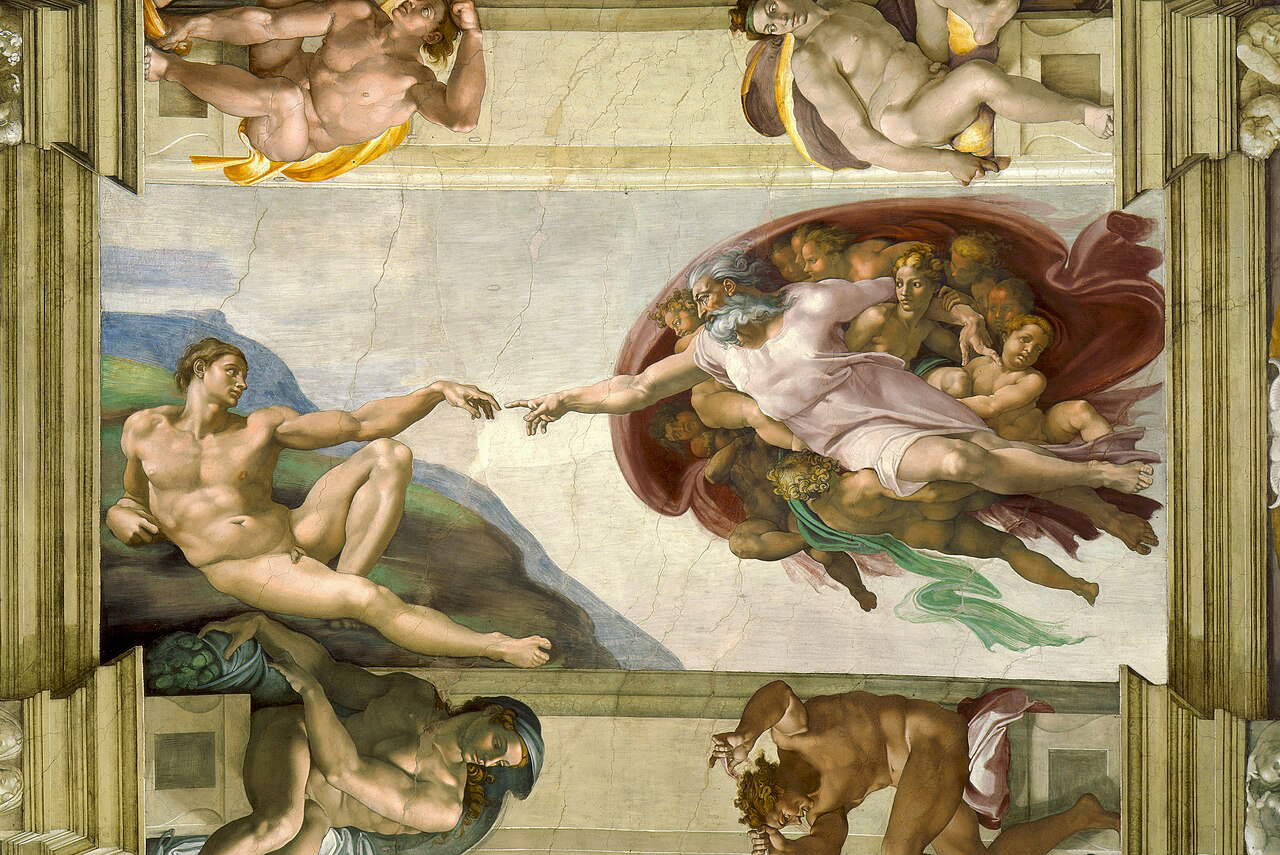

The work sums up several suggestions, as well as being a cornerstone of Garofalo’s production, a fixed point from which his entire career can be reconstructed, being his first dated work. Art historian Michele Danieli has emphasized possible links with works from the height of the Renaissance that Garofalo was able to see directly in Rome, precisely in 1512, when he most likely had to travel to the capital of the Papal States following a diplomatic mission of Alfonso I to Pope Julius II. We do not have the certainty that Garofalo was part of the mission, but given that at the time it was not uncommon to find artists in the context of diplomatic legations, and given that his art seems to reflect, starting at a precise moment in his career, what was being painted in Rome precisely during that turn of the year, the circumstance is entirely plausible. It seems that the duke, and with him undoubtedly the painters as well, had been particularly impressed by the frescoes that Michelangelo was finishing on the vault of the Sistine Chapel: the Ferrara delegation, in fact, on July 11, 1512, had the opportunity to go up on the scaffolding of the Chapel and visit the Vatican Rooms. “Signor Ducha,” one of the Ferrara delegates, Giovanni Francesco Grossi, wrote to Isabella d’Este, “went up the vault with several people, tandem each one a pocho a pocho se ne vene down de la vollta et il Signor Ducha restò up with Michel Angello who could not be sated to look at those figures et assai careze gli fece di sorte che Sua Excellencia desiderava el gie facesse uno quadro et li fece parlare e proferire dinarij et li ha inpromesso de fargiello”. The work with Minerva and Neptune is fully fitting for the date it bears (it is initialed “NOV 1512” on the stone in the foreground) precisely because of its obvious links with the Roman Michelangelo and Raphael, and for this reason it is also considered a watershed work in the context of16th-century Ferrara art, precisely because starting from this painting the painters of Ferrara would open themselves, without any kind of prejudice and with a certain precocity, to Roman novelties.

According to Danieli, the figure of Minerva, with her foot resting on her helmet, another iconographic attribute, and her torso tilted to the left, “echoes the mock statue of Apollo in the background of the School of Athens; and the gesture of the raised arm of Minerva herself, with a muscular anatomy totally unprecedented in Garofalo, seems to repropose Michelangelo’s very famous one in the Creation of Adam in the Sistine Chapel, publicly discovered on October 31 of the same year, but probably visible in July, at the time of Alfonso’s ill-fated ambassadorship to Julius II.” It is not just a matter of individual quotations, however: “the turning point with respect to the previous production is undeniable, starting above all with the setting: never before had Garofalo measured himself with such a calm, symmetrical and solemn rhythm, with a group of such monumentality, and its success shows the uncertainty of the beginner.” An approach that nevertheless does not deny the memory of what Garofalo looked at in the previous phase of his career, starting with the landscape ch’è of evident Giorgionesque influence: even, Roberto Longhi traced the same figures of Neptune and Minerva to a hypothetical recollection of the figures of the Fondaco dei Tedeschi painted by Giorgione himself (an opinion so cumbersome, that of Longhi, that it prevented for a long time, according to Danieli, that Garofalo’s painting be considered in the light of the Roman novelties).

A fundamental work for Ferrarese art, but whose true meaning remains to be discovered

Even before its possible political significance, Garofalo’s masterpiece is important above all for the fate of the arts in Ferrara, from that moment, from that 1512, increasingly open to Roman art. The importance of this work in the context of Ferrara art of the time is, moreover, now shared and widely accepted. Less clear, however, are its propagandistic implications, since no documents are preserved that can help us shed light on the context in which the painting was born. Thus, we do not know why it was painted three years after the battle, whether it was really commissioned by the duke, or what setting it was intended for.

There are, however, some circumstances, recalled in an essay by scholar Alessandra Pattanaro, that might clarify the circumstances of the eventual commission. Indeed, in August 1511, again in the course of the war of the League of Cambrai, Ferrara had laboriously succeeded in regaining Polesine and the city of Rovigo, including the salt pans of Comacchio that had often been at the center of clashes and rumblings between the Duchy and the Republic. Again, Alfonso I was among the commanders of the Franco-Ferrarran forces that defeated the alliance between the Papal States and the Empire at Ravenna on April 11, 1512, at the end of what is believed to be the most violent battle fought in Italy in the sixteenth century. It was not, however, a decisive victory, so much so that a long diplomatic phase ensued, within the scope of which Alfonso I’s mission to Rome recalled above also falls: in fact, the duke hoped to obtain from the pope the revocation of the excommunication that had been inflicted on him two years earlier and, above all, to regain possession of the territories he had lost during the war, although the outcome of the mission was politically unsuccessful. Therefore, it cannot be ruled out that Garofalo’s painting was made at the end of these events: Minerva, in this context, can be read as an allegory of religion due to the effect of that “ancient Minerva-Mary equation, attested since the Middle Ages,” Pattanaro writes, which would lead the female figure to call to herself "the concept of peaceful Minerva, Venus Victrix, Virgin Mary and Religio.“ So much so that in the seventeenth century the arrow was transformed into a cross, later removed with the restorations (however, there are still engravings from the painting in which it is possible to see how Garofalo’s work was modified). Evidently, Alfonso I did not want to celebrate himself as master of the Po, as victor over the Venetians: in this case, the work would have been painted immediately after the battle of Polesella, and then perhaps there is some reason to think that it would have been ”a real smargiassata," noted scholar Alessandro Ballarin, even though it was seen that, even years later, Alfonso I did not fail to be represented in the guise of victor of the Serenissima. Moreover, the idea of Alfonso I’s high regard for himself would not be undermined should one not give up identifying him as the god of the sea.

It is probable, at the very least, that Alfonso I did not just want to be portrayed as the ruler of the waters: perhaps, he also intended to present himself as a moral victor in diplomacy, and this was not so much to assert his own prerogatives before the political protagonists of the time, but rather, probably, to strengthen internal consensus, given that the summer of 1512 had not procured great successes for the duke: he had not obtained from the pope the territories that Ferrara had previously lost (after the Polesella victory there had in fact been many Ferrara reverses: the duchy had lost several cities such as Carpi, Finale Emilia, Bondeno, and especially Modena, occupied by the papal army in August 1510), it had had to suffer the occupation of Reggio Emilia by the Urbino army, which at that stage of the war was allied with the pope, and Garfagnana had also been invaded. In short, the territory of the duchy had now been reduced to just Ferrara and a few surrounding areas, which included Polesine and the cities of Argenta and Comacchio. Probable, then, that Alfonso I needed some form of internal propaganda.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.