It was 1222 when theUniversity of Padua was founded: eight hundred years of history making it one of the oldest universities in the world. The study in Padua immediately became one of the points of reference for legal studies, which flourished not only in Padua but also in the Studia established at some of the city’s convents and monasteries (the Eremitani convent, for example, was home to an important Studium generale). Witness to this fervent season in the field of jurisprudence is a manuscript preserved in the University Library of Padua, Codex 941, which contains the Digestum vetus: it dates from the first half of the 12th century and is one of the oldest codices that hand down the first partition of the Digestus, which was commissioned by Emperor Justinian between 530 and 533 and returned to circulation precisely between the 11th and 12th centuries. The Digest, which itself was part of the Corpus iuris civilis, was a collection of fragments of works of Roman jurisprudence that were to serve as a legislative reference for the empire: it contained rules on property, contracts, family law and other matters. The Digestum (which derives from the Latin digestus, past participle of digerere, meaning “to distribute,” “to classify,” referring to the order that the jurists appointed by Justinian had given to the subject matter) was divided into fifty books, and the locution Digestum vetus refers to the first twenty-four.

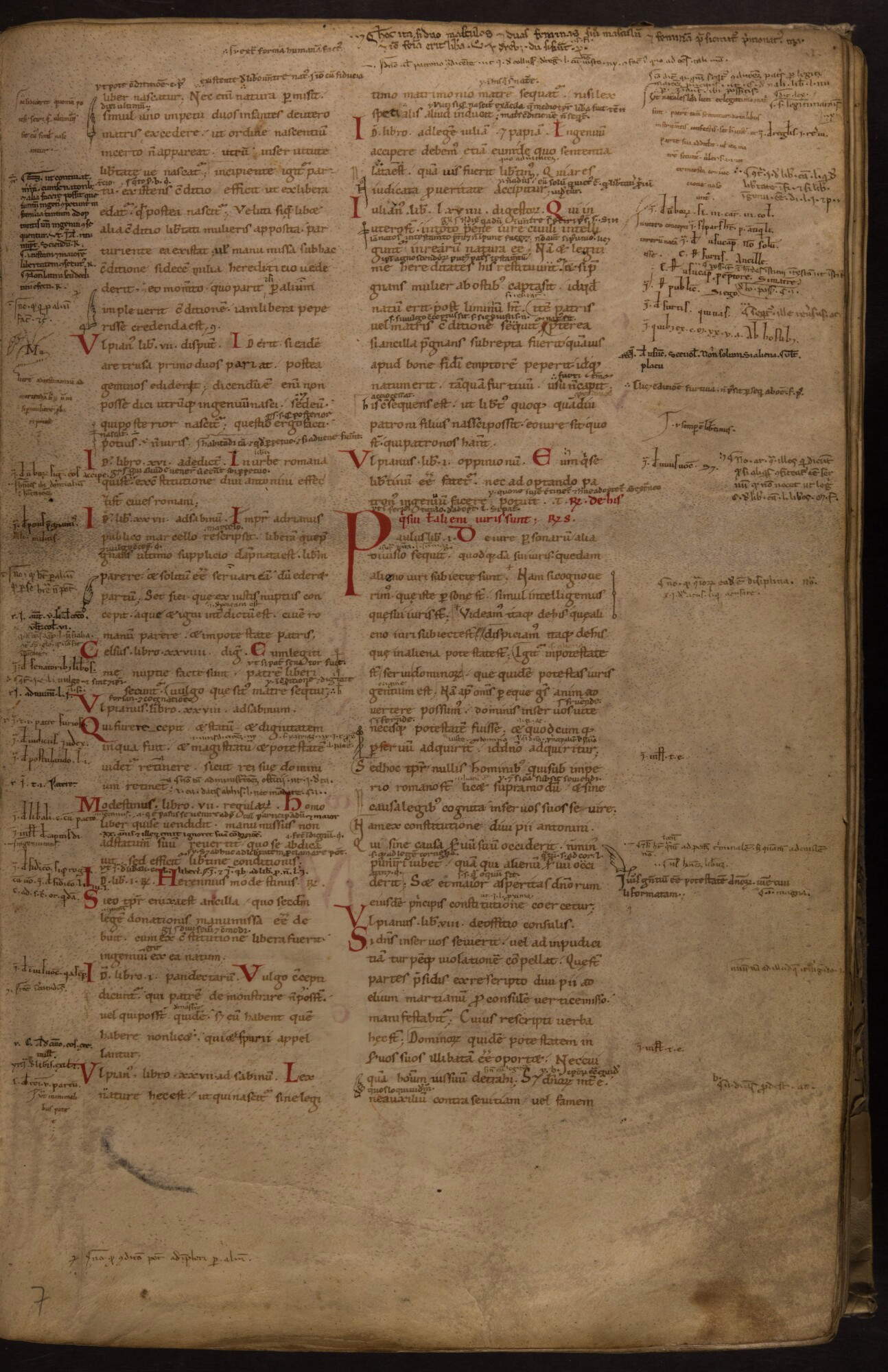

The Digestum vetus in the University Library of Padua is also one of the oldest codices bearers of that version of the Digestum that would come to be called the Littera Bononiensis (“Bolognese Letter”) or Vulgate, a redaction of the Digestum on which studies were being conducted at the University of Bologna. The Digestum vetus, moreover, had been glossed (i.e., commented on) by some of the most famous jurists of the time, including the celebrated Irnerius, an academic and glossator of Germanic descent who was among the founders of the Bologna study and among those who rekindled attention to the legislative texts of the Justinian age. Such is the importance of the Paduan Digestum vetus, after all, that these texts were common study material in early European universities, on which doctores taught and students learned. In addition, Codex 941 also contains many glosses from the 12th-14th centuries, which relate the thought of many famous medieval masters of law, such as Martin, Bulgarius, Rogerius, Azone, and others. The Digestum vetus of the University of Padua would in fact have been used throughout the 13th century and even in the early 14th.

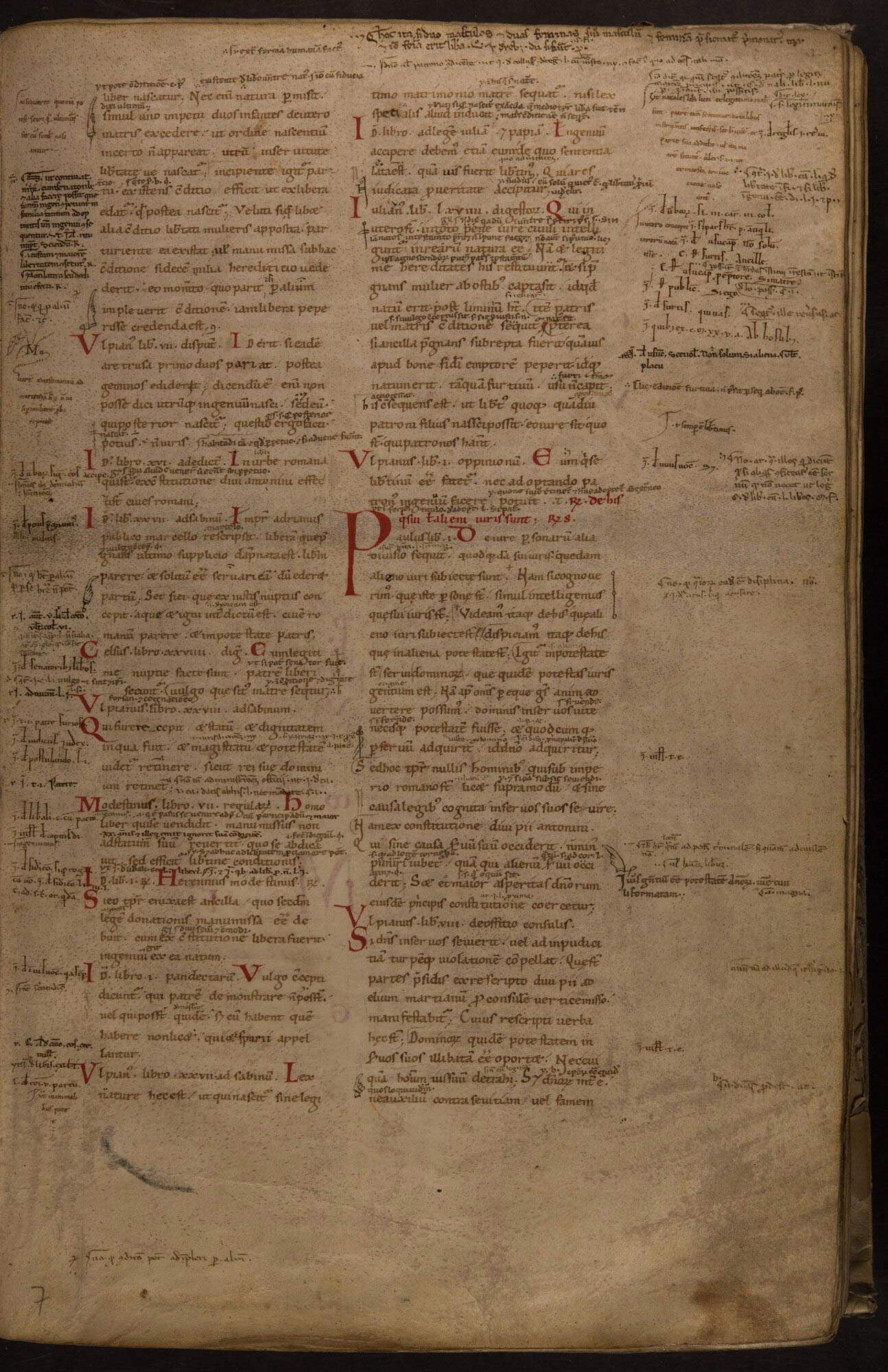

As mentioned above, the codex comes from the library of the Augustinians of the Eremitani convent: this is attested by a 14th-century possession note traced on paper 198v, which reads “Liber ordinis fratrum Heremitarum sancti Augustini concessus ad usum fratris Augustini de Plebe,” or “This book of the order of the hermit friars of St. Augustine is granted for use to Brother Augustine of Piove di Sacco.” Scholar Lavinia Prosdocimi described the Digestum vetus as probably the most important illuminated codex of those from the library of the Eremitani that are now in the possession of the University of Padua. The manuscript was still in the availability of the friars of the Eremitani in the seventeenth century: on the first paper of the manuscript there is in fact another note, with a marking that can be dated to a period between the end of the seventeenth and the beginning of the eighteenth century and that has been attributed to the hand of Evangelista Nomi, who was chancellor of the Eremitani convent in 1691. After the suppressions of the monastic orders in the Napoleonic era, between 1806 and 1810 the codex was deposited, along with others from the same library, in the monastery of Sant’Anna before being deposited in the convent of San Francesco and later arriving, between 1836 and 1841, at the University Library of Padua, which has since become its owner.

We do not know where exactly the Digestum vetus of the University of Padua was produced: perhaps in a scriptorium located between Bologna and Mantua, scholar Giovanna Nicolai has speculated (according to others, instead, between Modena and Bologna), and it is therefore likely that before reaching Padua the codex wandered among the studia of Bologna, Modena, and Reggio Emilia. The text, consisting of 198 sheets of parchment, is written in minuscule carolina tarda, from the first half of the 12th century: minuscule carolina was a script whose origins date back to the late 8th century and which, by virtue of its practicality and the speed with which a text could be written if it was used, soon became established in several European regions. The name is due to the strong connection that the birth of this script had with Emperor Charlemagne: in fact, it is believed that the Carolingian minuscule was born through the action of Abbot Alcuin of York, one of the leading figures of the Carolingian Renaissance (in Medieval sources the same script was called littera antiqua or littera Francisca). Thus, the Carolingian minuscule had become, Nicoletta Giovè Marchioli explained, “the graphic expression of Carolingian politics and cultural production,” capable of imposing itself “progressively as a totalizing script, used in both book and documentary spheres, in both public and private acts.” Moreover, because of its great clarity it was able to be successful for centuries, so much so that it was still used, as seen in Codex 941, by 12th-century copyists. Giovè Marchioli defines it as an “extremely posed and crisp script, with a rounded outline, in which the basic unit that characterizes its flow is the single letter,” characterized by clarity and extreme airiness that “are accentuated by the presence of rather wide interlinear spaces, a circumstance that allows both upper and lower rods to be very widely spaced.”

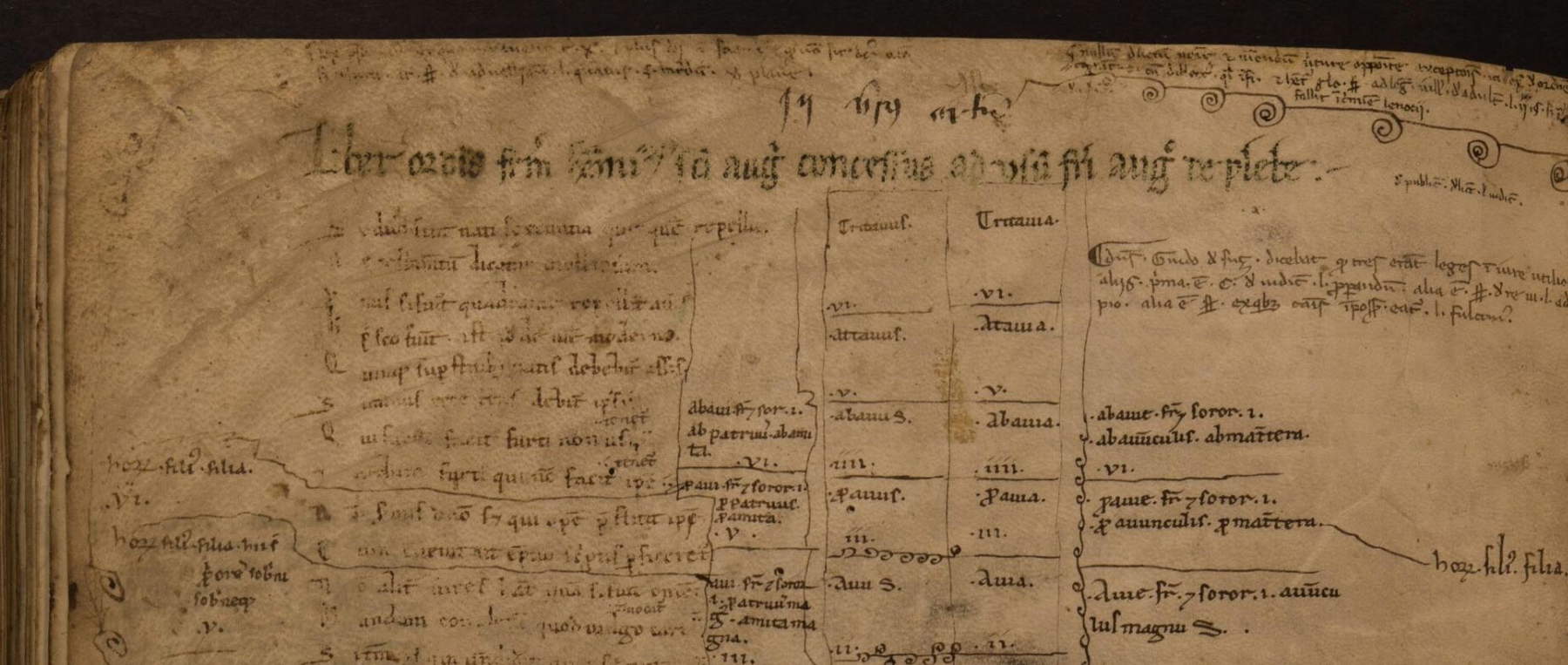

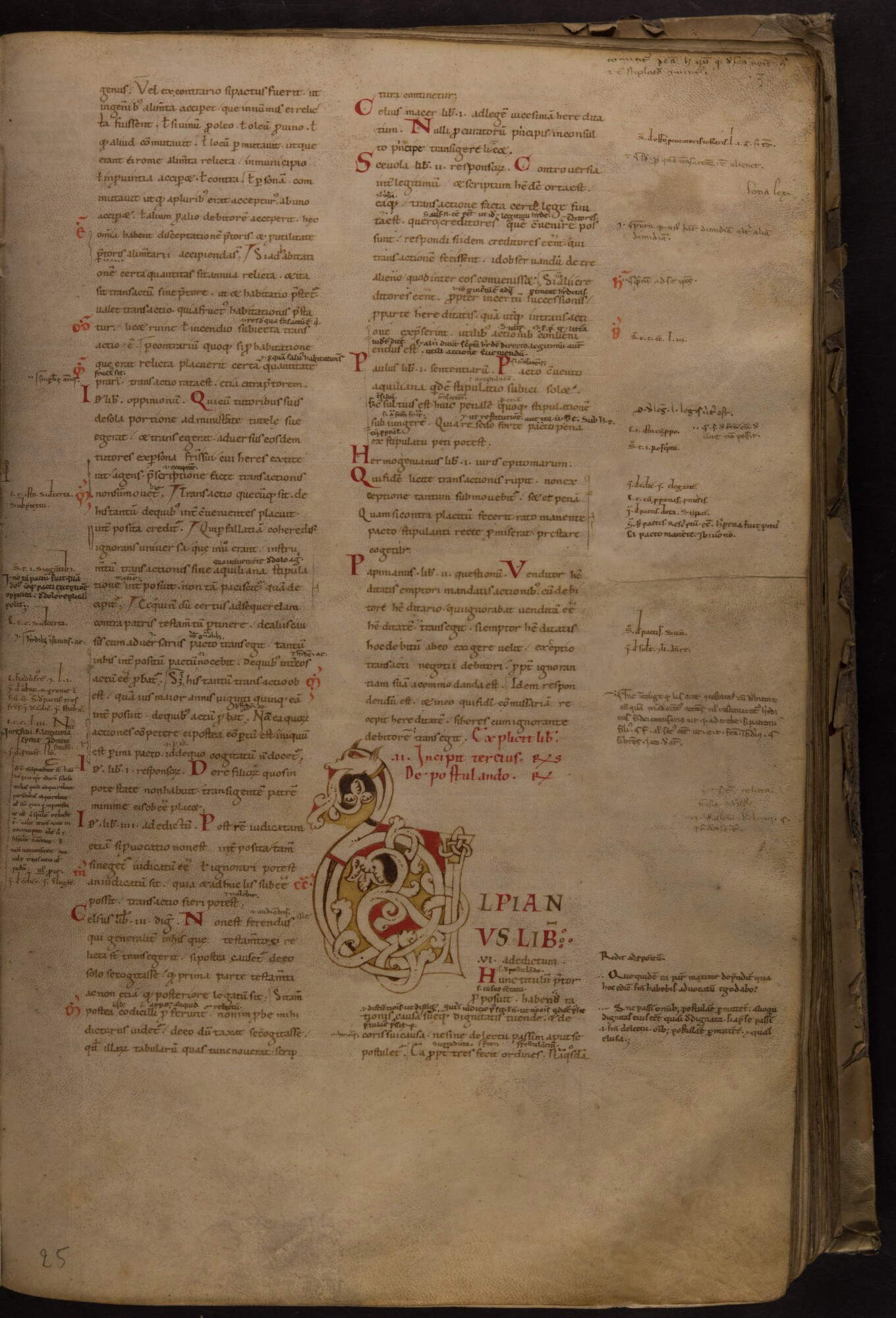

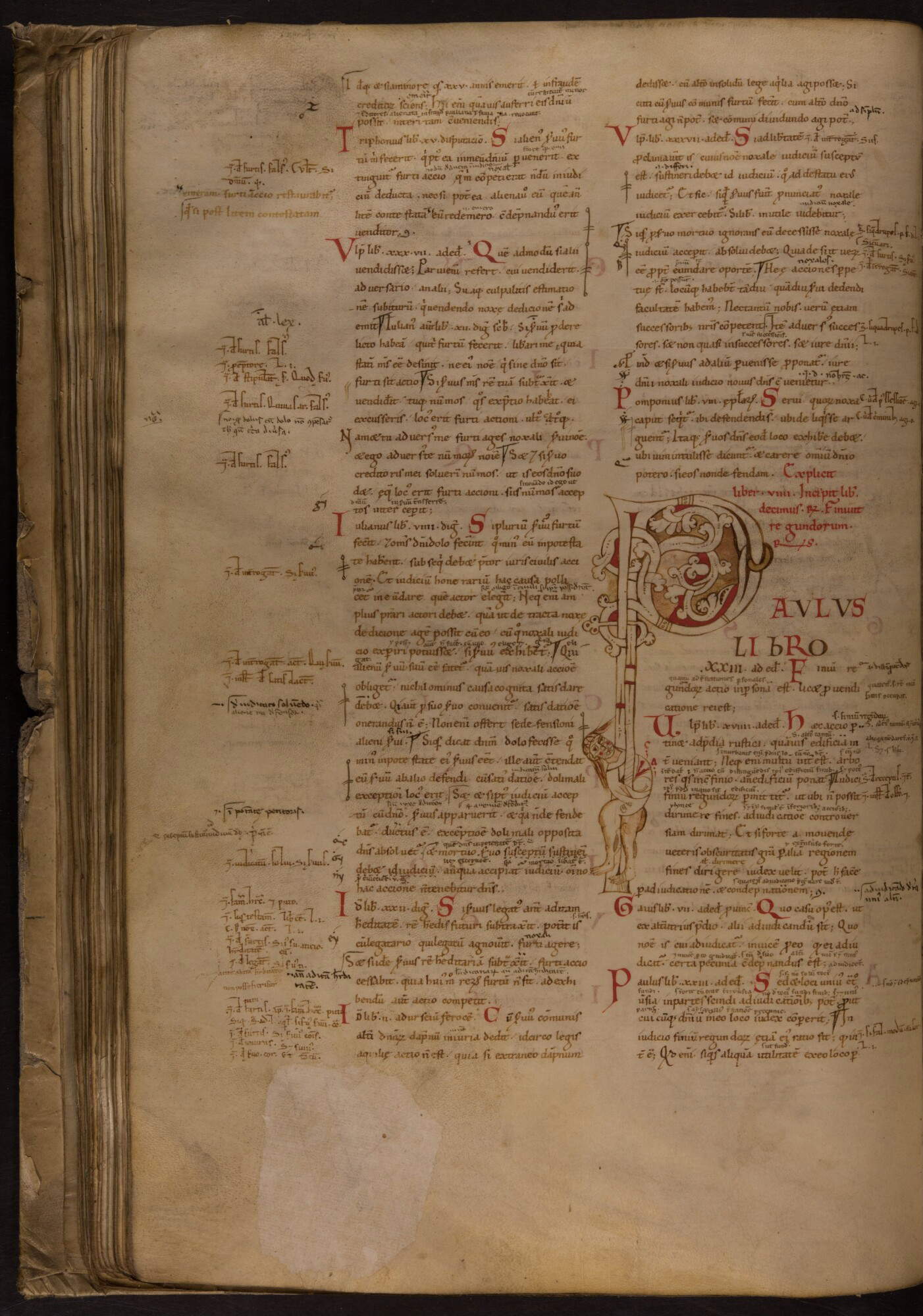

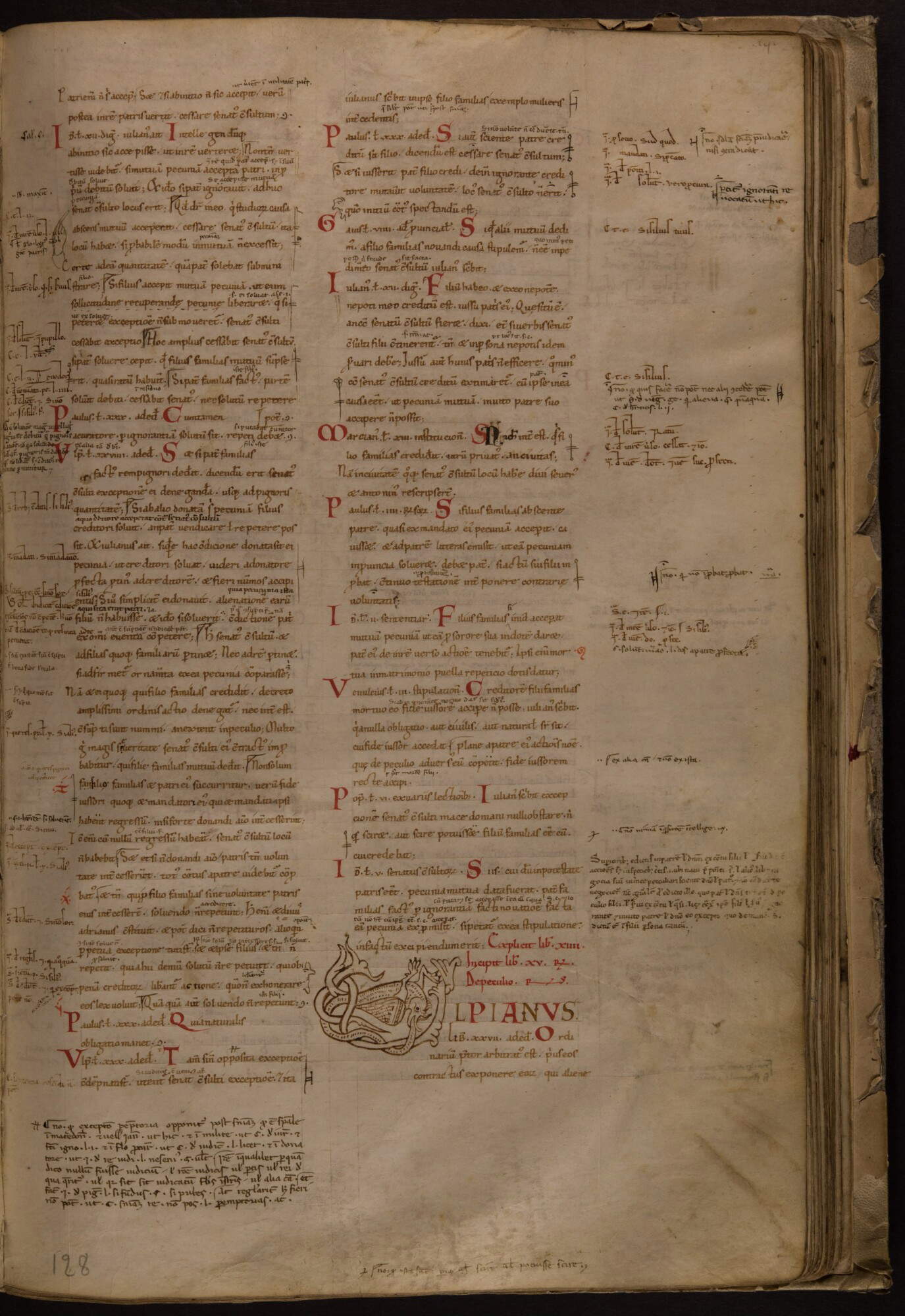

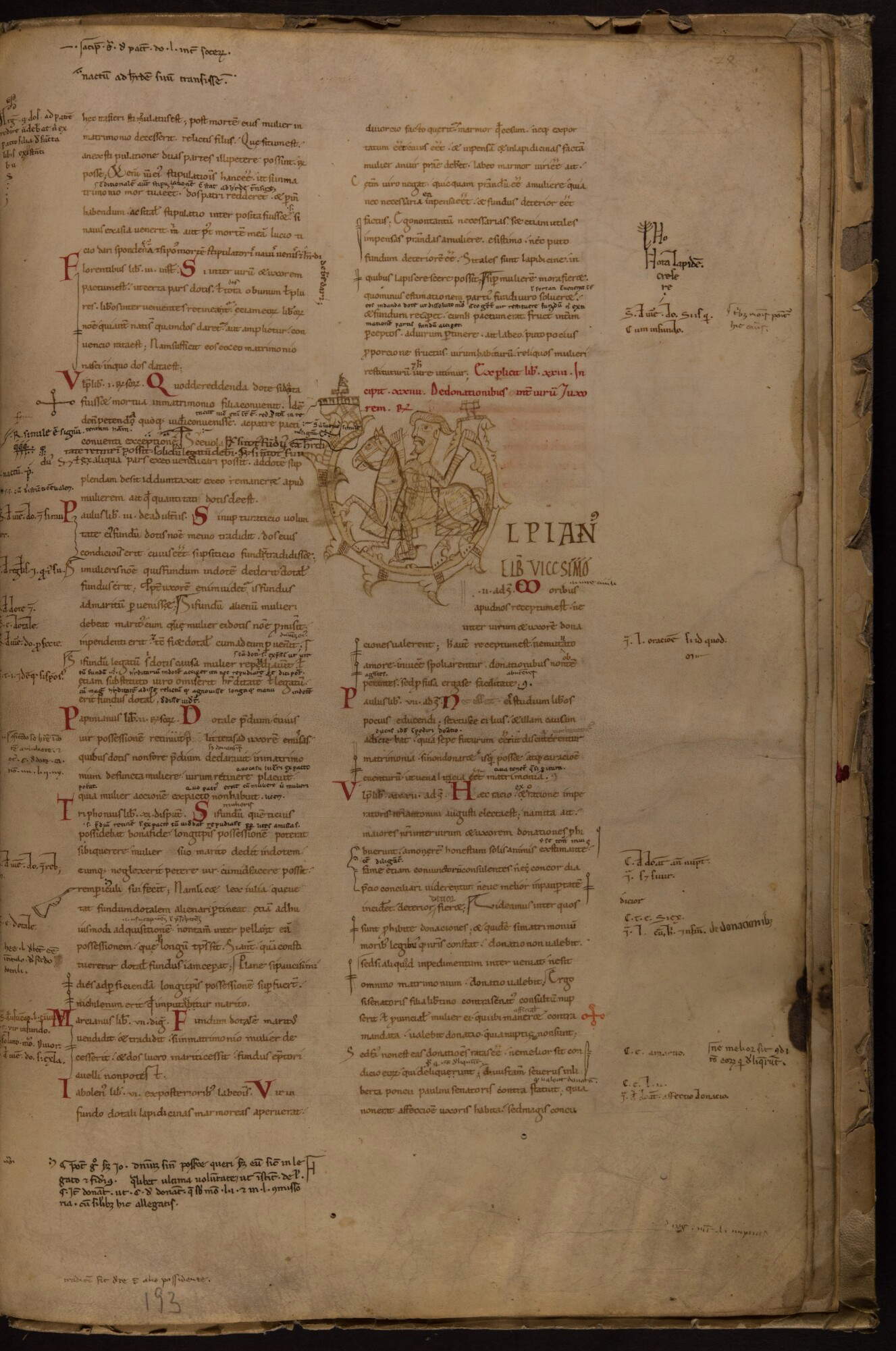

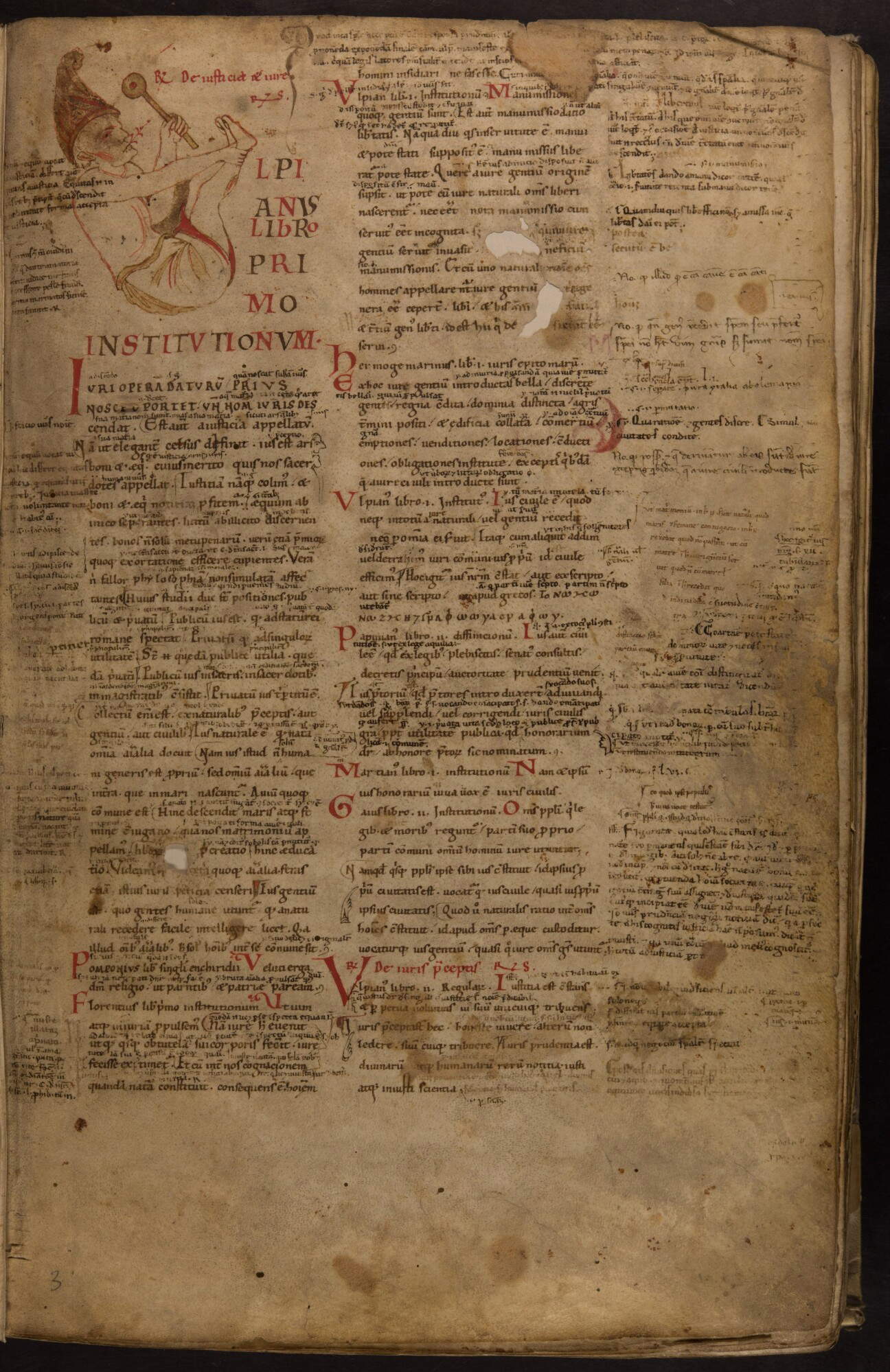

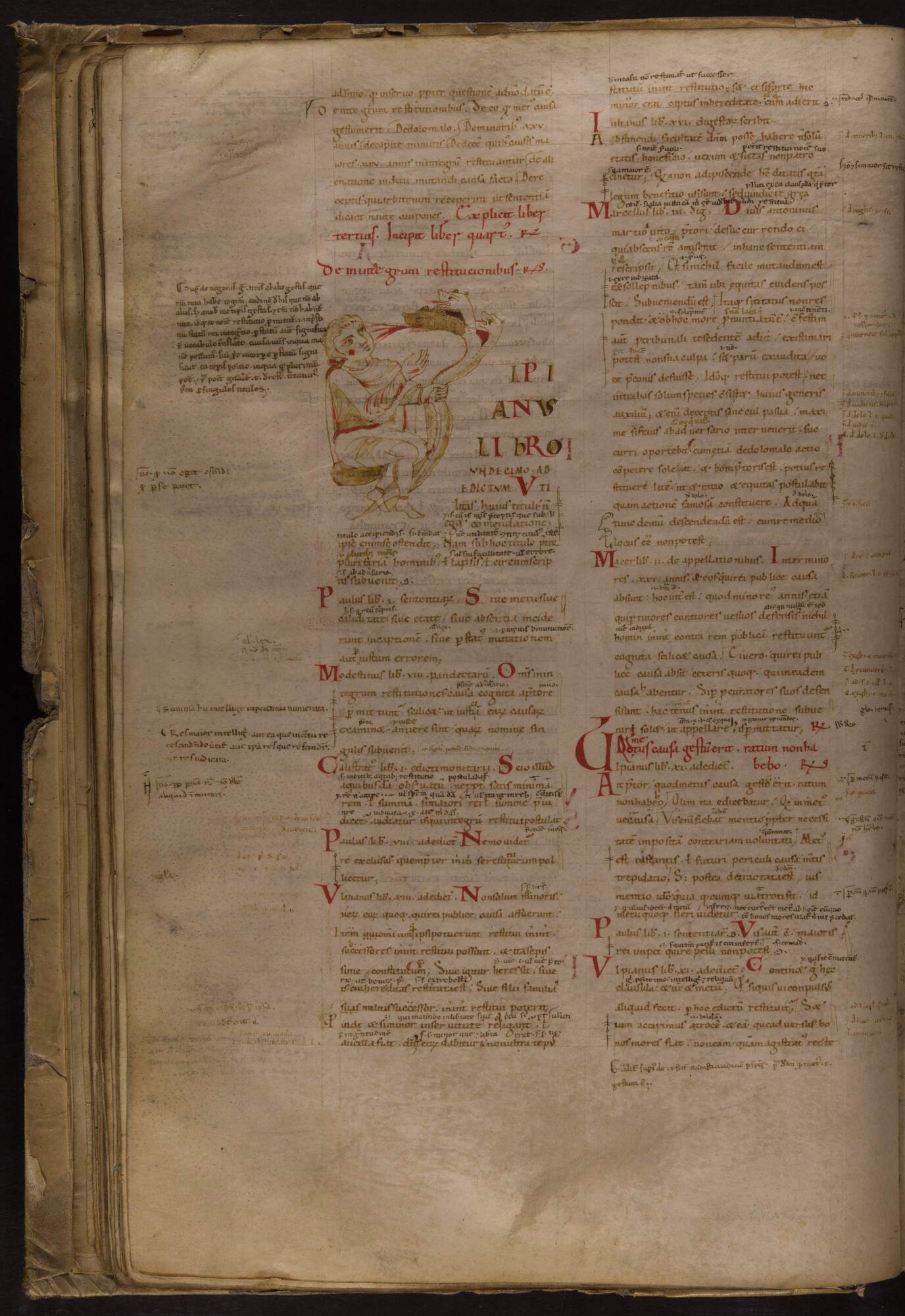

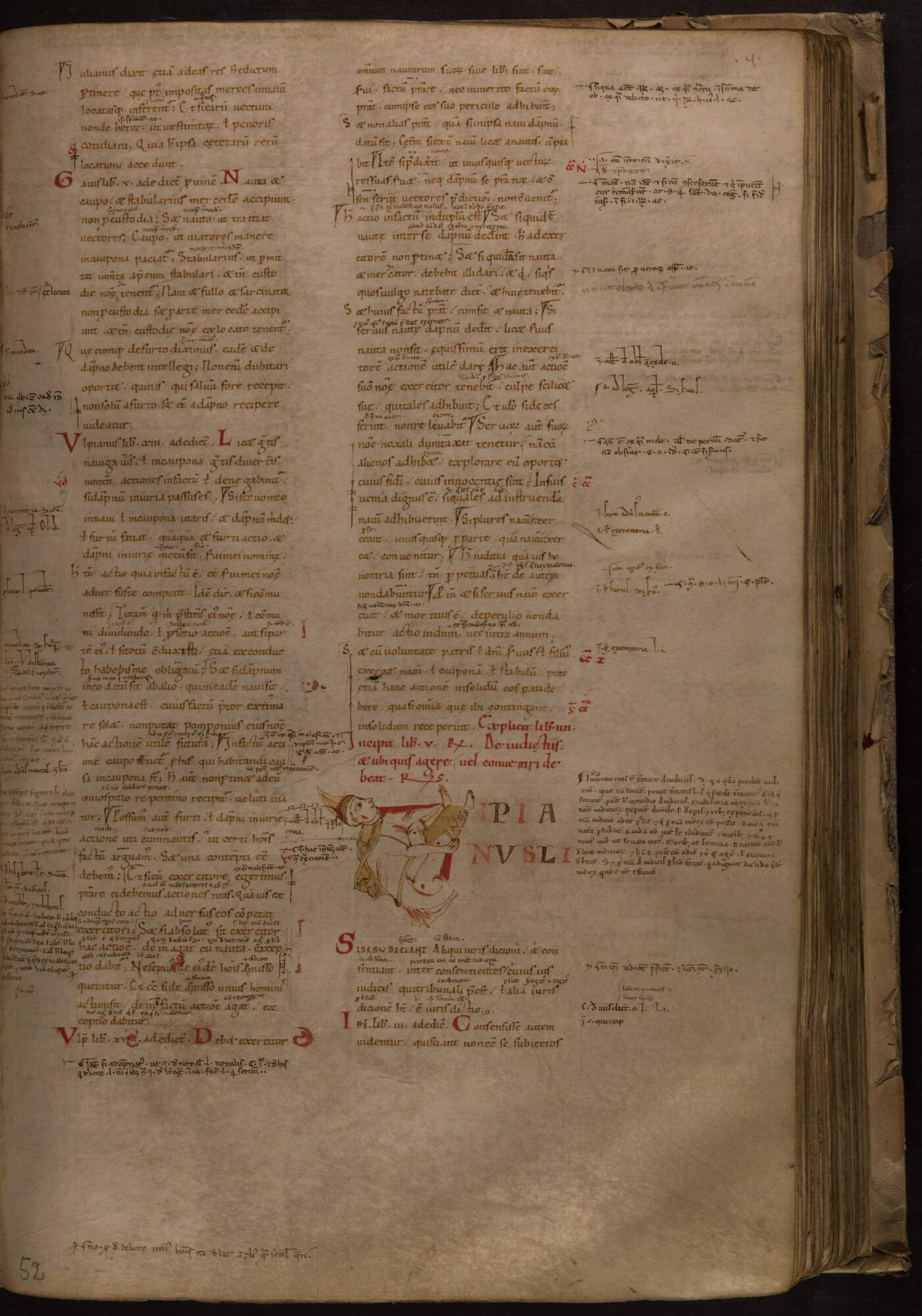

However, the interest of the Digestum vetus of the University Library of Padua also lies in the decorations found between its pages, which testify to one of the earliest phases of the decorations of the Corpus iuris civilis books, which would later flourish especially in Bologna. The book is not illustrated with miniatures, nor are they particularly elaborate decorations, since only the incipit initials of the books are mentioned. Most of the letters (nineteen in all) are decorated with plant motifs (racemes or intertwined), on red and yellow-ochre colored backgrounds; some also feature dog-headed protomes (such as the initial U on folio 25r), and in one case there is even a human figure, intent on holding the shaft of the letter P (on folio 94v). However, there are also more valuable initials, such as that on folio 128r, with a griffin, or that on 193r, which instead bears a knight, and then again three strange allegorical images: one at the beginning of the text (folio 3r), with a young man dressed in a tunic and wearing a Phrygian cap on his head and who, seated, lifts his legs holding them with his right hand while holding a rattle with his left; a young man in classical dress, placed at the beginning of Book IV, throttling a three-headed dragon and which, according to scholars Leonardo Granata and Gianluca Del Monaco (the latter author of an important iconographic study on manuscript 941), is to be identified as the episode of Hercules with the Hydra of Lerna; a final figure at the beginning of the fifth book with a character similar to the one on folio 3r, but without a rattle. According to Del Monaco, the illuminated set of the Digestum vetus of Padua “appears to be the most articulate and refined among the codices that constitute the oldest manuscript tradition of the work”: the other codices in fact have only simple decorated initials.

The three singular allegorical figures open questions about their function. Giovanna Nicolai, at the suggestion of Chiara Frugoni, has proposed identifying the two young men in acrobatic position with the figure of theinsipiens, or the fool who in the Psalms denies the existence of God, but if so, it would be necessary to admit that such iconography is unicum, since it is not attested otherwise before the thirteenth century (first theinsipiens takes, if anything, the guise of a sovereign). Besides, the thirteenth-centuryinsipiens presents very different characters than the figures in manuscript 941 anyway. Del Monaco believes, however, that these figures should be traced back to "a subject indeed related to what was to be the depiction of the biblical fool from the thirteenth century onward, namely the ioculator or histrio, the comic actor of the Roman theater, often mentioned by ancient and later medieval Christian writers as an example of immorality." It is a figure that finds many parallels in the psalters (the collections of psalms) between the 12th and 13th centuries, “finding in nudity and acrobatic movement its distinctive features.” Musical instruments are also often part of the outfit of these figures, although most often they are wind instruments. The idea of including this figure in the text may respond, according to Nicolai, to the need to offer a figuration of a stultus that appears in a tale about the origins of law that a thirteenth-century gloss accounts for.

The episode of Hercules and the Hydra of Lerna also has no immediate relationship to the Justinian text, however, Del Monaco explains, “it is significant that the theme of the twelve Herculean labors has an imperial connotation in the culture of the European Middle Ages perhaps as early as the controversial Herculean panels of the front panel of the throne probably donated by Charles II the Bald to Pope John VIII on the occasion of thecoronation in Rome in 875, namely the so-called Cathedra Petri preserved within Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s bronze monument in St. Peter’s in the Vatican,” and consequently Hercules choking the Hydra could be symbolic of the ruler defeating hostile forces, with direct allusion to the origins of Justinian’s law. We do not know who were the miniaturists who made the decorations. According to Del Monaco, however, the style of the ornamental motifs and initials harks back to the scriptorium of the abbey of San Benedetto Po, San Benedetto al Polirone, founded in 1007 by Marquis Tedaldo of Canossa. In fact, the decorative motifs hark back to some works certainly created in that scriptorium.

For the unusual iconographic choices (such as those just mentioned), for the elegance with which the initials are decorated (with a closeness to Polironian models or in any case referable to Matildic cultural circles), for the illustrious models, the Digestum vetus of Padua can be considered, according to Del Monaco, in terms of decoration, “the most significant manuscript among the witnesses of the oldest manuscript tradition of the work.” A singular interweaving of art and jurisprudence, then, that tells much about the origins of one of the world’s oldest universities.

The University Library of Padua is the oldest of Italy’s university libraries: it came into being in 1629 as the “publica Libraria” in 1629, to “commode” and “decorum” and “major ornament” of the Venetian university. Its first seat was in the Jesuit convent near Pontecorvo (today’s civil hospital), while the first librarian was the humanist Felice Osio, the creator and main supporter of the establishment in Padua of a modern library structure as a function of the university. The original library holdings consisted of the 34 manuscripts and 1,400 printed books on legal subjects that had belonged to Bartolomeo Selvatico, professor of law at the Studio, donated in 1631 by his son Benedetto, professor of medicine. In 1632 the library was moved to the prefectural palace, in the Capitaniato Square, in the Sala dei Giganti, and was later enriched by various gifts. In 1773, after Simone Stratico was appointed librarian, the reading rooms were expanded and very important collections were acquired: in just three years the library’s holdings grew from 13,000 to 40,000 titles. The library’s first season ended with the fall of the Venetian Republic: the library was closed from 1797 to 1805. Upon reopening and for the first two decades of the 19th century, the Institute acquired a large number of books accumulated in Padua, in the former monastery of Sant’Anna, following the suppression of religious corporations by Napoleon. Manuscripts, incunabula and printed books from the libraries of some 40 monasteries including that of the Dominicans, Augustinians and Theatines of Padua, the Benedictines of San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice, the Discalced Carmelites of S. Giorgio in Alga, as well as the holdings of prestigious libraries, were thus forfeited. With the second wave of suppressions, in 1867, after national unification, there was a new increase, with an overall increase of about 13,000 works, including many of considerable scientific and literary value.

In 1912, after nearly three centuries, the Library was moved from the Sala dei Giganti to its present location, the first state-owned building constructed in Italy with modern criteria specifically for library use, according to a design by engineer Giordano Tomasatti, consisting of two parts, a two-story forepart with the offices and rooms for public use, and a five-story book tower on the rear part, used as a warehouse for book deposits. In the center of the forepart is the atrium with “pincer” staircase connecting with the upper floor. Since December 1974 the University has been part of the Ministry of Culture.

The Library’s holdings amount to 2,733 manuscripts, 674,128 printed books, 1,281 incunabula, 9,622 cinquecentine, and 6,617 periodicals. Among the oldest manuscripts are St. Jerome’s Breviarium super psalterium, Bede’s Super Cantica Canticorum and St. Gregory’s Liber dialogorum; among the most recent are the autograph manuscripts of the philosopher Roberto Ardigò. The subjects most represented are history and theology, followed by literature, philosophy, jurisprudence, medicine and mathematics. Of particular interest are texts on Venetian history, including theItinerario per la terraferma veneziana, an autograph by Marin Sanudo. Also noteworthy are St. Augustine’s De civitate Dei, which belonged to Bishop Ildebrandino Conti and features an autograph distichum by Petrarch, some musical fragments from the 14th-15th centuries, and the autograph of the humanist Sicco Polenton Exempla ad filium Modestum. Among the incunabula, the oldest edition owned by the Library is that of the Epistolae of St. Jerome, datable to about 1468. Among the most valuable works are the parchment and illuminated volumes of Matteo Bosso, printed in Florence by Francesco Bonaccorsi in 1491 and in Bologna by Platone dei Benedetti in 1495. Illustrated Incunabula, on the other hand, include Valturio’s De re militari (Verona, 1472) and Schedel’s Liber chronicarum (Nuremberg, 1493). The library also holds Shakespeare’s first “in folio,” containing the English playwright’s opera omnia, printed in London in 1623, of which only two or three other copies are known outside England. The Library also possesses some of the masterpieces that came out of Bodoni’s printing press. Also of great importance is the collection of Prints, which testifies mainly to the activity of Veneto copperplate engravers between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and, subsequently, to the work of the main regional lithographic establishments.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.