When one admires a painting whose protagonists are elderly people segregated in a hospice, what one is contemplating is “not a normal aspect of our culture, so to speak,” wrote art historian Michael F. Zimmermann a few years ago, speaking of the paintings that Angelo Morbelli had set at the Pio Albergo Trivulzio in Milan, the institution that, since 1766, the year in which it was founded at the behest of Prince Antonio Tolomeo Gallio Trivulzio, had continued to welcome the city’s poor, especially the old and sick. The moment one is forced to measure oneself against a poor interior inhabited by lonely, sad, stooped and abandoned elderly people, one becomes the object of a confrontation “that is not part of the normality of life,” a confrontation that obliges us to become aware of a dimension far removed from our daily experience, especially if this is comfortable. And, consequently, to take a position (a position, of course, “lived within society”), or at least to redefine one’s way of seeing things. Morbelli’s paintings, in other words, move from two points of view: “that of the characters depicted and that of the viewer,” and the perspective of the viewer is not only that of the author, but is that of society as a whole. Thus, it is not the painter who conditions the viewer: it is society itself that prompts the viewer to provide an interpretation of the work. According to Zimmermann, “it is not Morbelli who frames the social ’real’, but it is the viewer who cannot remain indifferent to what the painter shows him.”

The scholar believed that Pellizza da Volpedo and Morbelli were the greatest in dealing with reality in this way, that is, telling it through paintings capable of challenging society. And this is what Morbelli tried to do on several occasions with his paintings at the Pio Albergo Trivulzio, a place the Piedmont-born artist frequented throughout his career. He had gone there for the first time in 1883, at the age of 30, and the contrast could not have been more stark: he young, vital, moved by the desire to document life in the shelter, which he began to study by means of drawings and photographs, many of which are still preserved, though affected by the ravages of time. On the other hand, the guests of the Pio Albergo Trivulzio, old people removed from society because they were no longer considered useful, workers who had put themselves at the service of the nascent industrial society and who became outcasts at the moment when no one needed them anymore, elderly people without means of economic sustenance condemned to spend the last glimpses of their existences together with so many other derelicts like them, in huge promiscuous environments, far from any affection. The first rejects of a world that was beginning to become frenetic, to uproot centuries-old habits of a society that until then had been largely peasant, to overwhelm anyone who did not have the strength to keep up. Entitled Days... last! the painting that inaugurates this poetics of abandonment, desolation, and suffering is entitled Days... last! a youthful work, preceding Morbelli’s Divisionist turn. A successful work, exhibited at Brera, capable of winning the prestigious Fumagalli Prize and a swarm of benevolent criticism. A work of “merciless chronicle,” as Giovanna Ginex, one of the most authoritative names in Morbelli criticism, has well written.

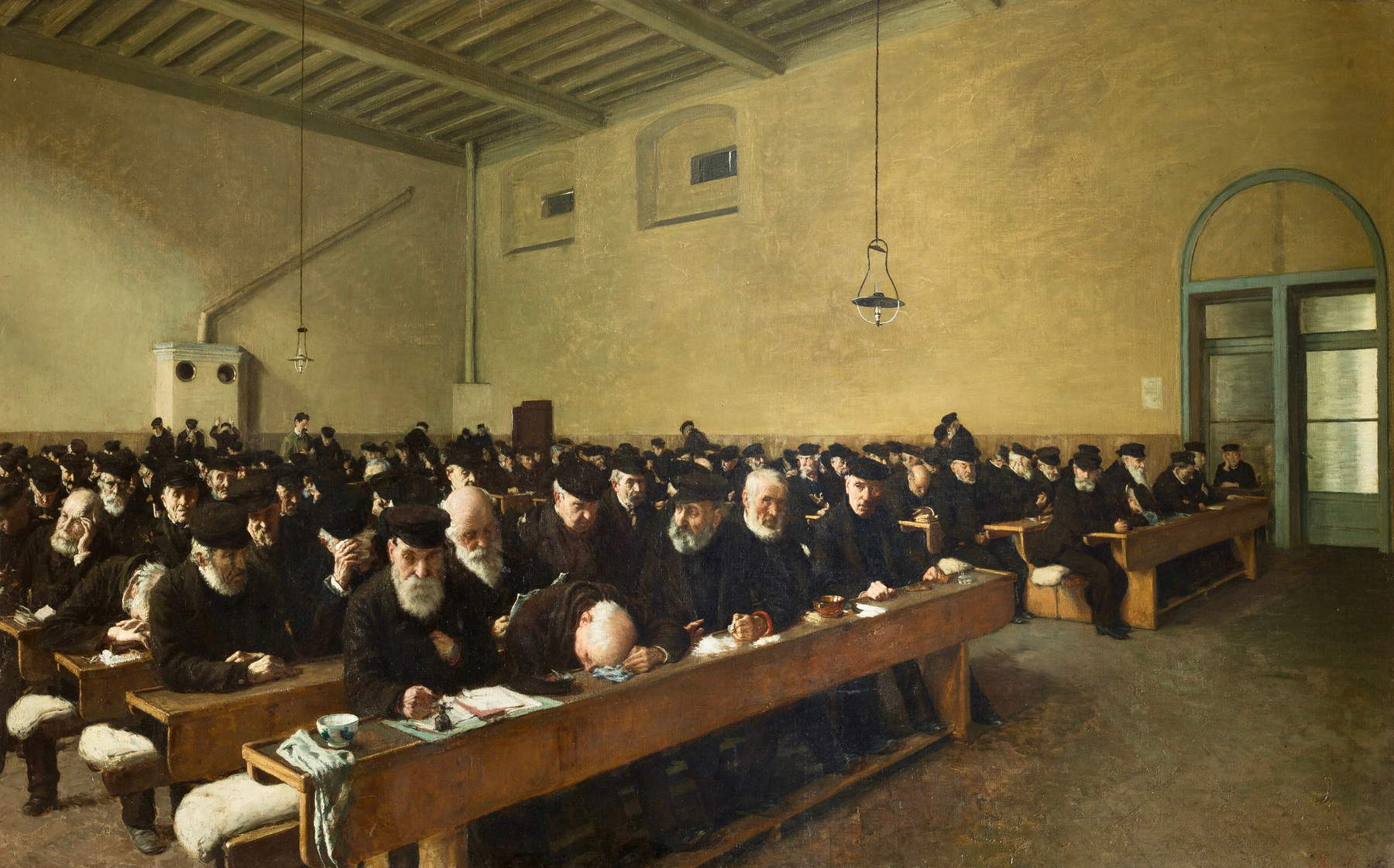

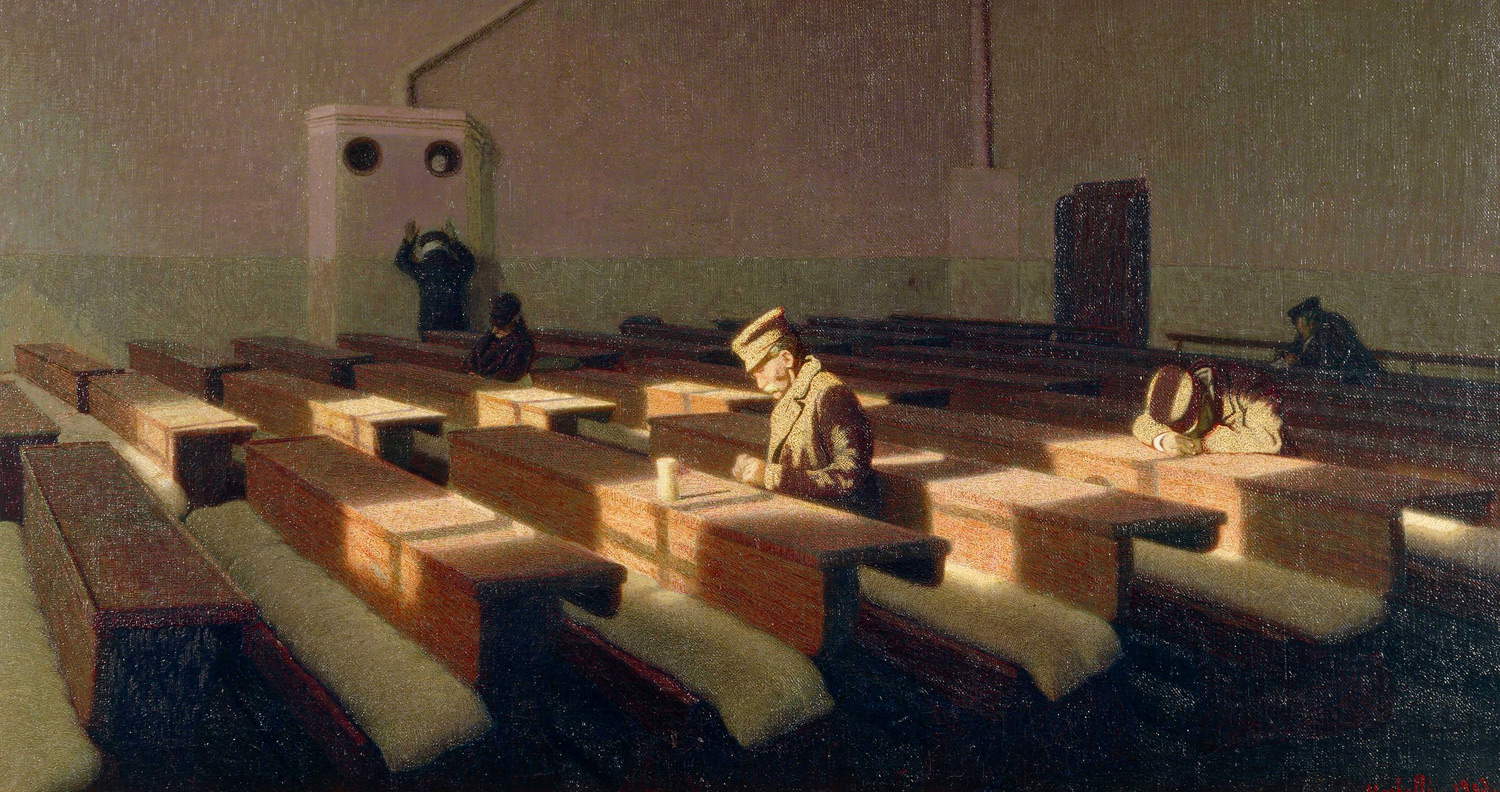

Morbelli’s brush captures a slice of everyday life in the large hall of the Pio Albergo Trivulzio, at the time still housed in the prince’s palace in Contrada della Signora: a few years later, in 1910, the premises would be moved to the current building on the Via per Baggio. The elderly guests sit on the long benches in the large room devoted to small daily activities, and the grazing light brings out their dull, melancholy faces: some read, some look lost, some hold up their heads and think, some try to write, some sleep, some look around bewildered. Fortunato Bellonzi suggested grasping the tension of this scene by observing some specific details: the ordering of the benches and walls, the lamp hanging from the ceiling that also becomes a character, the pipe that cuts obliquely through the back wall, the character who, in order to seek some warmth, rests his hands on the huge stove. Details that help reveal Morbelli’s attitude: that of the artist who investigates reality more to emphasize the human condition of those who suffer it than to denounce a concrete problem.

|

| Angelo Morbelli, Last Days! (1882-1883; oil on canvas, 98 x 157.5 cm; Milan, Galleria dArte Moderna) |

And the Pio Albergo Trivulzio was at that time anything but a hospitable place: the inconveniences were many and urgent, and they made the existence of the poor old people obliged to spend their last years here all the more burdensome. Looming, meanwhile, was the problem of overcrowding, which incidentally also emerges in the margins of Days... Last! Promiscuity was another dilemma, since many of the elderly were forced, due to the absence of adequate space, to share the same rooms and sleep in vast dormitories: the quickest way to facilitate the spread of disease (and it will be worth mentioning that, given also the conformation of the rooms, the shelter workers were unable to separate the healthy from the sick). These, however, are themes that do not emerge at first glance: at the center of Morbelli’s paintings is, if anything, “marginality understood as anguished exclusion from active life, as a lack of real motivation to survive, as disengagement from family affections” (so Luciano Caramel): the sufferings of these old people are interior even before they are physical, and it is for this reason that it is impossible to find in Morbelli the illness in its most palpable tangible evidence, made up of signs that rage on the body (contrary to what happened, for example, in Daumier, a pioneer of nineteenth-century social denunciation painting, where figures of old people bent by the passing of the years or by the lashings of misery are not rare). In contrast, Morbelli’s old people always appear in a state of good health, at least apparent. Perhaps it is because the root of everything isabandonment. Perhaps because what leaves the deepest wounds is not the disease, but the awareness of having been cast aside, discarded, betrayed, forgotten. Perhaps it is because all the problems that have historically plagued and continue to plague the elderly in hospices today are problems of humanity, even before they are medical or health problems. Perhaps, what really hurts most is to slowly fade into oblivion. The old people in the Pio Albergo Trivulzio therefore are nothing more than empty shells left empty, suspended in bitter, painful and indefinite waiting.

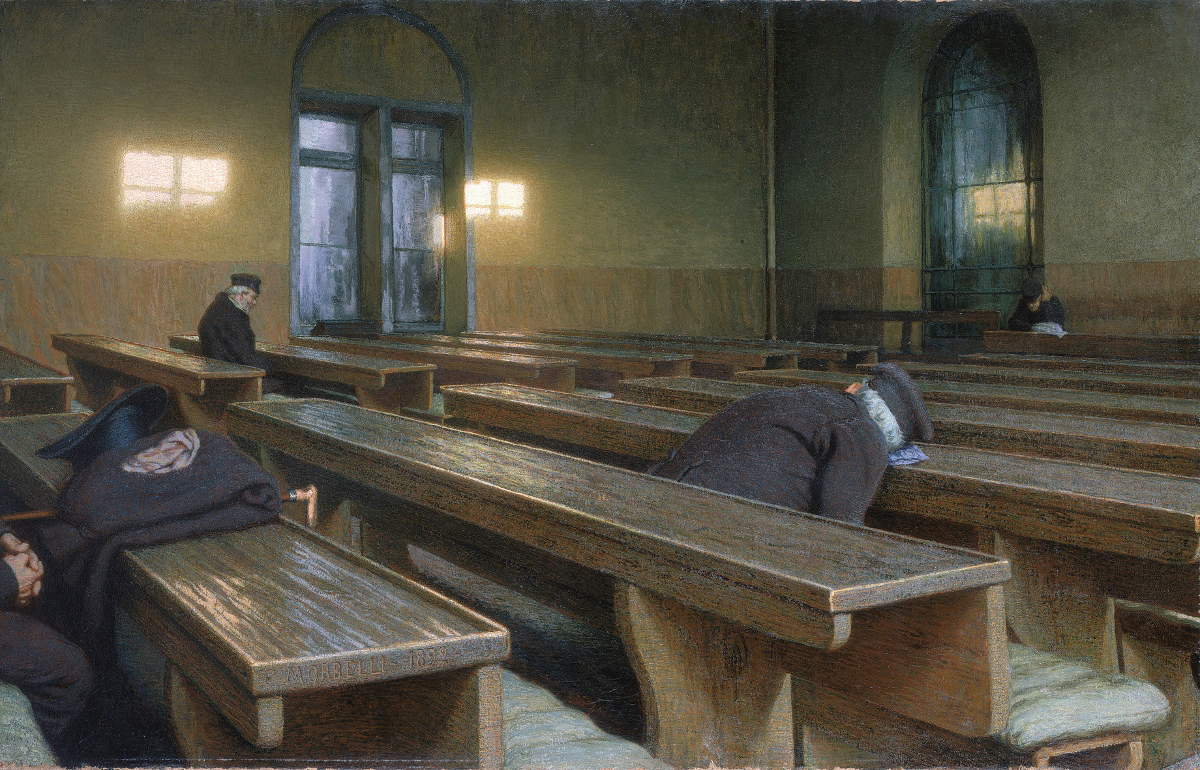

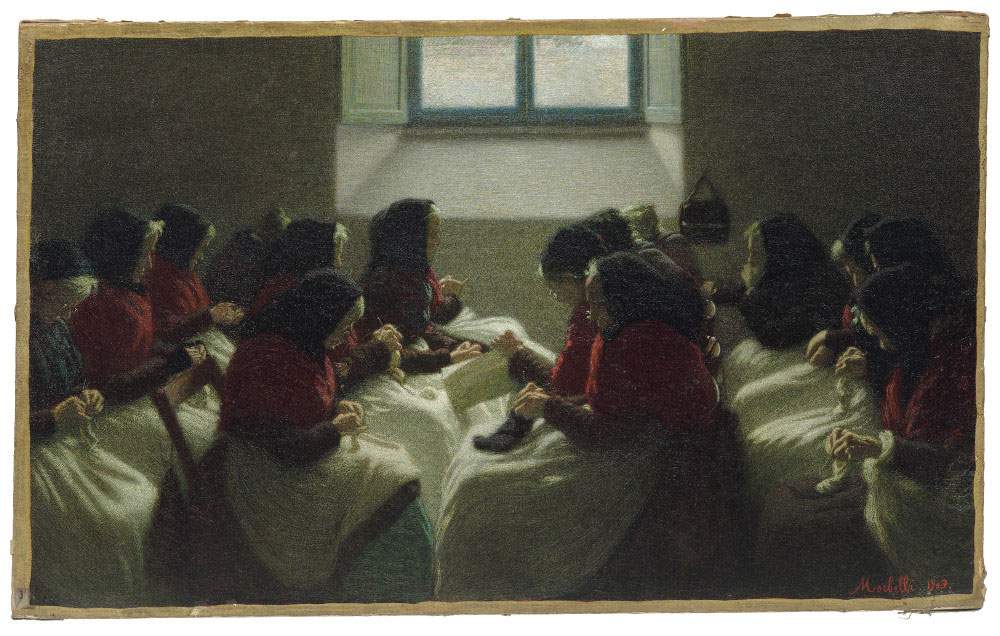

Therein lies that “disconcerting sadness” of which Corrado Maltese spoke when he referred to Morbelli’s paintings, filled with interiors “with little old men and women grazed by the last rays of sunset.” Maltese had in mind some of the most evocative works executed in the Milanese hospice: for example, the 1892 Giorno di festa al luogo Pio Trivulzio, now at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris (the work was a great success in France: it was shown in 1900 at the Universal Exhibition in Paris along with Viatico of 1884, a work depicting a funereal farewell to a guest of the Trivulzio who had passed away, and on that occasion it was awarded a gold medal and purchased by the French state), or the later Un Natale al Pio Albergo Trivulzio, of 1909, now at the GAM in Turin. The theme of the festive day in the hospice, an occurrence that exacerbates the dramatic sense of loneliness that oppresses the existence of the old folks abandoned in the shelters, was not new to European painting: Ginex enumerates precedents such as Hubert von Herkomer’s Christmas at Chelsea Hospital, from 1878, or Léon Frédéric’s Noël à l’hospice, a work from 1884, which Morbelli probably knew and from which he started for his paintings that narrate Christmas Day in the large rooms of the Pio Albergo Trivulzio. The rays of sunlight filtering through the windows draw large paintings of light on the walls and desks, and all they do is reiterate the obligatory existential isolation of the old people, emphasizing the vastness of the empty space: the few guests are there alone, spaced out not only physically but also in their souls, they are motionless, they let themselves go. Notice how obsessively the theme of the old man who leans on the stove with both hands returns: almost as if the only warmth these poor human beings can still feel is that of a thermal appliance.

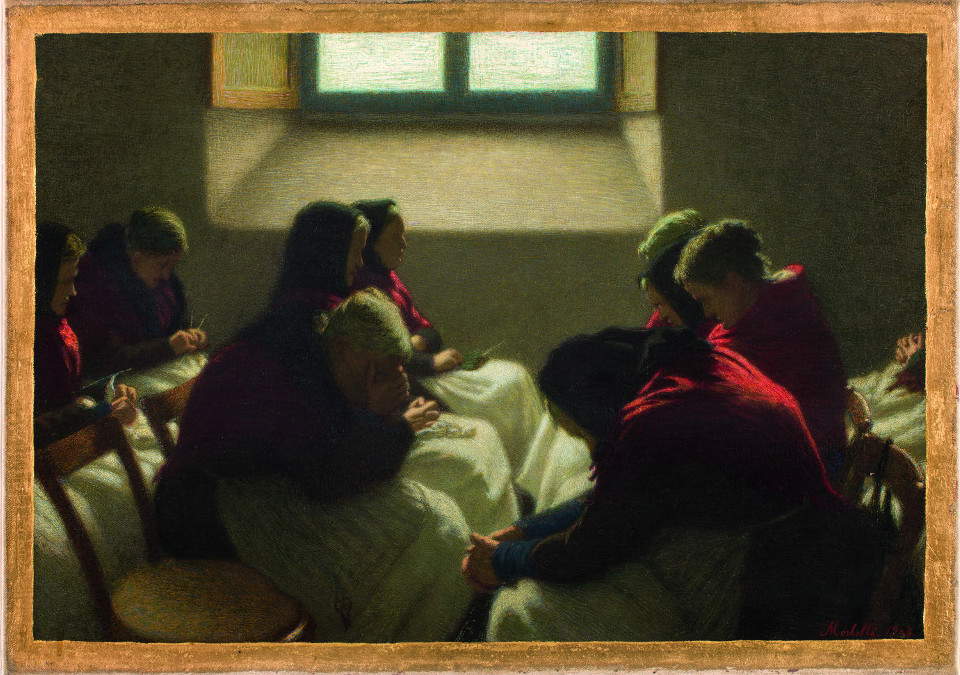

We do not have full knowledge of Angelo Morbelli’s real intentions, but it is certain that a reading of the paintings at the Pio Albergo Trivulzio based on this distressing sense of despair had already emerged at the time: in a commentary published in the 1904 Christmas issue of L’illustrazione popolare, a family newspaper published in Milan by the Treves brothers, it could be read that “they are certainly not happy, the poor old men whom the painter Angelo Morbelli saw in that asylum of poor old age, which is the Luogo Pio Trivulzio in Milan. They are old men who have lost all their loved ones; and they are left alone in the Ospizio; the other peers have been invited to the home of some surviving relative, of some friend... one of them clings to the stove, as if to the last vital thing that remains to him; the others stand pensively, bent over the deserted benches, at the pale ray of the winter sun, which penetrates the vast melancholy hall.” Even more elegiac tones will take on other later paintings, such as Inverno al Pio Albergo Trivulzio, executed in 1911 and which takes up, with a foreshortening with a photographic cut declined in a form, however, more intimate than many experimented before, an interior of the new headquarters in Via Baggina, the one in which the Trivulzio is still housed today: here, some elderly women are bent under a window from which filters a tenuous light that does not even manage to illuminate them: only one of them is illuminated, and turns her gaze outside. But they are all there, in a single room, spending a desolate day the same as all the others: the result is like an atmosphere of suspension, a sad and ineluctable waiting for the end.

|

| Angelo Morbelli, Feast Day at the Pio Trivulzio Place (A Christmas at the Pio Albergo Trivulzio) (1892; oil on canvas, 78 x 122 cm; Paris, Musée d’Orsay) |

|

| Angelo Morbelli, A Christmas! Al Pio Albergo Trivulzio (1909; oil on canvas, 99 x 173.5 cm; Turin, GAM - Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea) |

|

| Angelo Morbelli, Il Viatico (1884; oil on canvas, 112 x 200 cm; Rome, Galleria Nazionale dArte Moderna e Contemporanea) |

|

| Angelo Morbelli, Winter at the Pio Albergo Trivulzio (1911; oil on canvas, 72 x 148 cm; Milan, Galleria d’Arte Moderna) |

The interest in themes related to the days spent at the Pio Albergo Trivulzio later found a kind of organic arrangement in a cycle of six paintings that Morbelli executed in 1903 and presented that same year at the fifth Venice Biennale, in the Sala Lombarda, one of the many rooms dedicated to regional exhibitions. The rules of the exhibition stipulated that each artist could only bring a maximum of two paintings to the lagoon, but Morbelli had taken precautions in good time, writing in December 1902 to the secretary general of the Biennale, Antonio Fradeletto, to ask for a waiver, since he wanted to exhibit six or eight paintings in Venice. The request was granted, and Morbelli was thus able to present at the Biennale the Poema della vecchiaia, the series of six paintings made at the Trivulzio and having as its subject the theme of senility examined according to its most heartbreaking meanings: loneliness, boredom, nostalgia, sadness, abandonment, and death. The cycle had been exhibited in its entirety exclusively on that occasion: it was reunited only in 2018, for an exhibition at the Galleria Internazionale d’Arte Moderna di Ca’ Pesaro in Venice, which after a full one hundred and fifteen years was able to show the public the six canvases of the Poem of Old Age gathered together again.

“There is still much to be gathered in the matter of sentiment and picturesqueness”: so Morbelli wrote, on February 26, 1901, to his friend Pellizza da Volpedo, thus manifesting, for the paintings of the Milanese shelter, a sharing that, as we have seen, was dictated more by human motives than by political ones. Wanting to begin the reading according to the order in which the paintings had been exhibited at the 1903 Biennale, the first is Empty Chair, which introduces the theme of death: with a slightly off-center perspective cut (so as to give the impression of a film shot in motion, with the camera moving from one end of the camera to the other), Morbelli enters the everyday dimension of a sparse group of old ladies who, resigned, meditate on the loss of their companion in misfortune, symbolically represented by the chair left empty, an eerie allegory of the death that hovers over the shelters for the elderly (in the first draft of the painting, moreover, Morbelli had also included an umbrella for viaticum, which he later decided to remove so as not to present too explicit a funereal reference in the eyes of the subject). Mi ricordo quand’ero fanciulla, on the other hand, is set in the refectory of the women’s section of the Pio Albergo Trivulzio: here, the old women eat their park lunch (a little bread, a little wine) absorbed in their thoughts, without communicating with each other. The title of the painting, as was Morbelli’s typical custom, makes its meaning explicit: the ladies have that absent air because, far from their affections, disconsolate for an ending they evidently imagined different, forced into an anonymous environment along with so many other unhappy strangers, they can do nothing but live in memory. And the faint imprints of the past, as anyone who has had the good fortune to share part of his or her existence with an elderly person who has reached the final stages of his or her life knows, are of extreme importance to them, since it is the memory that is one of the few certainties capable of cheering them up. Old Socks is also a reflection on death: recently tracked down in Uruguay, it was the painting that was missing to recompose the cycle exhibited again in Venice. The two winters also takes up the theme of the old ladies at the window, with a thread of sadness due to the awareness that the protagonists are living the last times of their existence: the first winter is the one that stands outside the window and lets in a diaphanous light, while the second is the one experienced by the protagonists. Loneliness returns in Il Natale dei rimasti, which takes up the theme already experimented in 1892 with a large empty salon, inhabited only by five figures who do not interact with each other, but abandon themselves to their tragic thoughts (“on the feast day,” wrote Giovanna Ginex, “the salon is almost deserted, revealing the dramatic loneliness of those who have no family that can welcome them, not even for Christmas”). The last painting, Winter Siesta, is a reprise of Empty Chair with a change of angle and raised point of view.

The Poem of Old Age garnered excellent acclaim. Even Ada Negri wrote about it in the Corriere della Sera (“abandonment and senile misery are rendered with admirable and definitive synthesis”), and a young Margherita Sarfatti was also pleased, fascinated by the way the painter from Alexandria had tackled a social drama by emphasizing its existential aspects. Everyone admired the way Morbelli had defined, with intimate delicacy and lyrical refinement, the unhappiness of old age spent in a hospice. “Poverty and loneliness,” wrote art historian Elena Pontiggia, "mingled, in Morbelli’s works, with a continuous meditatio mortis, while the social denunciation was veined with a subtle bitterness, in the awareness that no progress, no revolution could ever erase the ineluctable epilogue of human affairs." As mentioned, Morbelli would return on several occasions to the subjects of the Poem of Old Age, but there is one painting that perhaps, more than others, could be considered a sort of concluding epilogue to the series: it is Dream and Reality, also known as the Triptych of Life, a work of 1905 that, not without Symbolist impulses, is distinguished by its meditative character imbued with sweet and mysterious nostalgia. The triptych is presented with two figures, a poor elderly couple, on the sides: they are seated in an interior, illuminated only by glimmers that emphasize their faces caught against the light. Both have fallen asleep, while they were attending to their small daily activities: a knitting for her, reading for him. The lady dozed off with the balls of yarn and needles still on her apron, while her companion put away his book, denoting that sleep was premeditated. In the center is an emotional nocturne, the element that makes this work one of the most moving in nineteenth- and twentieth-century Italian painting: on a terrace enclosed by an Art Nouveau balustrade, two young people embrace and let their tender feelings carry them away as they gaze at the stars, with her dreamily abandoning herself on his shoulder. It is the most obvious evocation of the memory that makes old age more bearable: the two elders recall that happy age that cannot return, trying to divert their thoughts from the bitterness that the future will hold, and from the sorrows of a present that condemns them to live on memories to make the sufferings of everyday life less unpleasant.

|

| The six canvases of Poem of Old Age on display in Venice (Ca’ Pesaro International Gallery of Modern Art) in 2018. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The six canvases of the Poem of Old Age on display in Venice (Ca’ Pesaro International Gallery of Modern Art) in 2018. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Angelo Morbelli, Empty Chair (1903; oil on canvas, 60 x 85 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Angelo Morbelli, Mi ricordo quandero fanciulla (Entremets) (1903; oil on canvas, 71 x 112 cm; Tortona, Il Divisionismo Pinacoteca Fondazione C. R. Tortona) |

|

| Angelo Morbelli, Old Stockings (1903; oil on canvas, 61.6 x 99.7 cm; Lugano, Cornèr Bank Collection) |

|

| Angelo Morbelli, I due inverni (1903; oil on canvas, 47 x 71 cm; Milan, Private Collection) |

|

| Angelo Morbelli, Il Natale dei rimasti (1903; oil on canvas, 61 x 110 cm; Venice, Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia, Galleria Internazionale dArte Moderna di Ca Pesaro) |

|

| Angelo Morbelli, Winter Siesta (1903; oil on canvas, 49 x 74 cm; Alessandria, Museo Civico e Pinacoteca) |

|

| Angelo Morbelli, Dream and Reality (Triptych of Life) (1905; oil on canvas, three panels, 112 x 80 cm, 112 x 79 cm, 112 x 80 cm; Milan, Fondazione Cariplo collection) |

One can conclude with a hypothesis put forward by Zimmermann, according to which Morbelli’s paintings of old age, while focusing on the human aspects of existence in the Pio Albergo Trivulzio (one can also derive, conversely, an idea of how precious the lives of the elderly are and how turrible a society that abandons them is), are not free from significant political implications. The starting point is the idea of the individual excluded from the community that Giorgio Agamben formulates in his Homo sacer. Sovereign Power and Bare Life: “the one who has been banished,” Agamben writes, “is [...] not simply placed outside the law and indifferent to it, but is abandoned by it i.e. exposed and risked on the threshold where life and law, outside and inside are confused.” The severe poverty in which large sections of the population find themselves (which, in Morbelli’s time, we must assume to be much wider than they are today) determines a situation in which institutions dispose almost completely of the lives of people who find themselves in distress, and since “the hospice systems were also intended to incarcerate poverty and illiteracy in some way,” Zimmermann writes, “it is certainly permissible to frame them in this perspective as well: old women and old men were kept alive by systematically taking away almost all their freedoms.” It is, in essence, a form of assistance that guarantees life in its purely biological sense, but excludes, with the aggravating circumstance of leaving the discussion in the public space. “Morbelli’s paintings,” Zimmermann concludes, “were important steps to bring these phenomena of politics made over people’s bodies into a realm of public discussion.”

To the best of our knowledge, Morbelli was not animated by the bold political consciousness that moved his friend Pellizza. However, it is safe to imagine, given his frequentations, given his interest in painting of even more explicit social denunciation, and given also the quantity of paintings dedicated to the theme of old age (the most recent studies count about thirty), that some more markedly political glimmer radiated, to some extent, the action of this great painter. The tragic fate of the elderly of the Pio Albergo Trivulzio, erased from society and forced to await their end in a shelter, is in Morbelli the most obvious symptom of the aberrations of societies founded on capitalist-type economic systems that, unable to completely abandon the individuals who make them up, simply exclude them the moment they are no longer of use. And perhaps even then, more than a hundred years ago, a painter, with only the tool of his art, tried to warn us.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.