When Albrecht Dürer drew the Castello del Buonconsiglio in Trento.

Buonconsiglio Castle in Trent is among the buildings that appear most often in the works of Albrecht Dürer (Nuremberg, 1471 - 1528): he depicted it at least four times, beginning with two famous watercolors that the artist himself marked “Tryt” and “Trint”, that is, the View of Trent from the North (1495) and the View of Buonconsiglio Castle from the North-West (1494-1496), respectively kept in the Kunsthalle in Bremen and the British Museum in London, to continue in Pupila Augusta, a pen and dark ink drawing executed between 1496 and 1500 and belonging to the Royal Collection, finally, in the burin depicting St.Anthony Abbot dated 1519 of which there are several examples (two of these are in the Metropolitan Museum in New York and the Pinacoteca Tosio Martinengo in Brescia). A place that therefore we infer must have greatly impressed the Nuremberg artist on one of his trips to Italy. However, it is not yet known with certainty when, for example, the British Museum drawing was made: scholars are divided between those who consider it to be the result of Dürer’s second trip to Italy (1505-1507), those who think it was made on the outward journey of his first stay in Italy (1494-1495) and those who date it to his return trip to Germany. In the catalog of the exhibition, organized precisely at the Castello del Buonconsiglio from July 6 to October 13, 2024, entitled Dürer and the Others. Renaissance on the banks of the Adige River, on the occasion of the centenary of its establishment as a museum, Luca Gabrielli, in his essay reconstructing the historical events that changed the appearance of the Buonconsiglio Castle over time, dates both the Bremen and London watercolors to Dürer’s first descent to Italy, in thelast decade of the 15th century, basically referring to architectural elements built between the years 1505-1506 and therefore not present in the watercolors. The appearance of the castle represented in both would therefore be, according to Gabrielli’s reconstruction, that prior to the significant interventions ordered by Prince-Bishop Bernardo Cles between 1528 and 1536. Observing these watercolors, however, it is evident, given the abundance of details, how Dürer wanted above all to concentrate on thearchitectural aspect of the places that most fascinated him and which, as if in a sort of memoir, he jotted down on sheets; less defined, on the other hand, are the so to speak naturalistic and urbanistic aspects, which the artist translated with patches of color.

Beyond the temporal placement of their creation, Dürer’s travel watercolors are considered masterpieces not only in the artist’s output but also in the history of European art. British scholar Kenneth Clark called them the “first sentimental landscapes of modern painting,” and Erwin Panofsky declared that these “show a clear advance not only in perspective, but also, and it is more important, in conception,” adding that “the whole takes on greater prominence than the parts, and each individual object, natural or man-made, is seen as participating in the universal life of nature.” And speaking of the London watercolor depicting the Castle of Trent he stated that “it is no longer a record but an image, so the depiction of the city of Trent is no longer a topographical inventory but a view.” They are, however, images that reveal a particular attention to detail, treating places and architecture as if they were portraits, and in this regard, Gabrielli recalls how Dürer, in his youth (according to what is noted by one of the earliest compilers of news about the artist’s life, a certain Johann Neudörfer from Nuremberg who had occasion to personally frequent the painter in the last years of his existence), devoted himself to depicting people, landscapes and architecture with the accuracy of detail typical of portraiture.

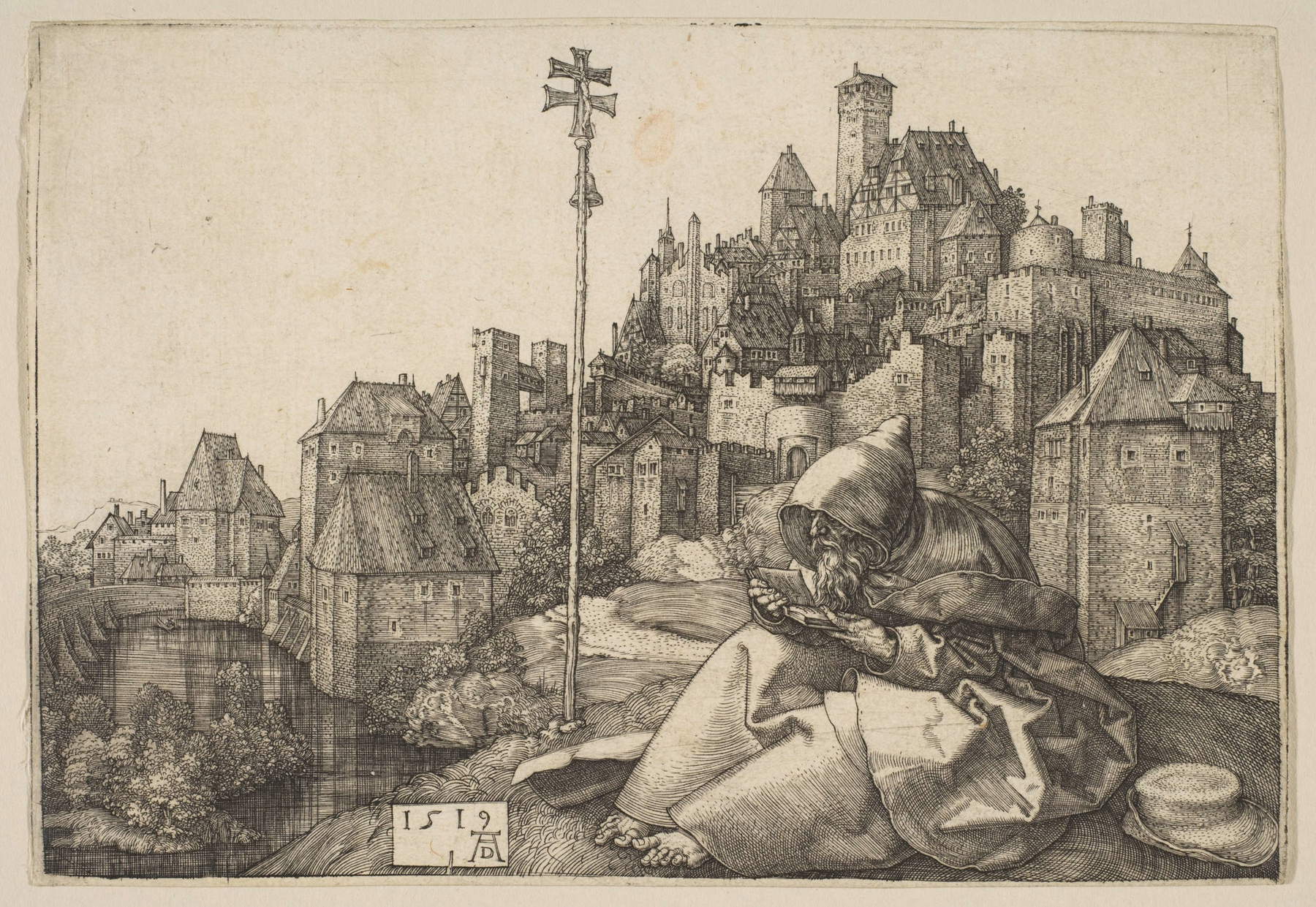

In theBremen watercolor, in which Dürer depicts with a view from the north the outline of Buonconsiglio Castle and the gate of San Martino and the portions of the city walls up to Torre Verde, the pointed spire of the Torre verde covered with green enamel-painted embrici: this element helps give a precise chronological indication of Dürer’s trip to Italy, for if the spire was erected between 1505 and 1506 it is assumed that the painter saw the tower in earlier years, probably in the 1490s. More precise and detailed than the Bremenwatercolor, although presumably made in the studio from sketches from life, theLondon watercolor, shown for the first time in Italy on the occasion of the exhibition, presents a close-up view of the castle illuminated by light from the west in the afternoon hours. The watercolor documents the state of Buonconsiglio Castle before the major interventions carried out by Bernardo Cles. Between 1528 and 1536, in fact, Cles promoted the building of a new representative wing, the so-called Magno Palazzo, which was connected to Castelvecchio, the main body of the castle. In addition, during this period, a large garden area was created, surrounded by a new and wider wall, which replaced the old one depicted by Dürer and built under Prince-Bishop Georg II Hack. This watercolor, therefore, provides valuable visual evidence of the castle in its configuration prior to these transformations.

The upper left corner of the sheet depicts the majestic main body of the castle, or as called Castelvecchio. Although there are some inaccuracies in the depiction of the battlements and the size of the openings, Dürer faithfully reproduces the structure as it had been renovated a decade earlier, thanks to the interventions of Prince-Bishop Johannes IV Hinderbach (in office from 1465 to 1486). The layout and functions of the spaces within the castle can also be reconstructed through the ancient inventories compiled between 1465 and 1527. Starting from the left, one notices the little wall connecting St. Martin’s Gate to the Green Tower, already mentioned in Bremen’s watercolor. This muraglione may correspond to the one described in the 15th-century inventories as the “green wall,” topped by a sturdy wooden bertesca that most likely served as a guard post. The cylindrical keep, significantly lower than the present configuration, is then seen. On the left, the castle shows its severe northern façade, already visible from another perspective in views of the Pupila Augusta and St. Anthony. On the right, on the other hand, the main elevation opens to the third floor, dedicated to ceremonial functions, with the so-called Venetian loggia, from which the prince and his guests could observe the city from above, whether for private contemplations or public ceremonies. In contrast, the trilobe windows of the large room north of the loggia, called the “long chamber,” remain hidden from outside view by the tower of the city wall.

Continuing southward, one notices the scaled facade of the central body, characterized on the third floor by two covered porches that correspond to the castle’s main hall, now known as the bishops’ hall, which is also connected to the loggia. On the lower floor is a balcony with metal grating that illuminates the vast hall used, among other functions, as a palatine chapel, as mentioned in the 1527 inventory. In the watercolor, only the red color of the arches and columns of the loggia suggests the refinement of the stone apparatuses and pictorial decorations of the interior, of which Albrecht Dürer could not have a direct perception, as he remained outside the barred gate of the walls. Invisible from the outside also remain the rooms used for the service functions of the bishop’s court, which included the rooms of the chancery, burgrave, captain, guards, cook and sutlers on the second floor, and those of the master of the house and cellarer, along with the rooms of the kitchen, silver room, bread oven and court refectory on the second floor. Also located in the vicinity of the castle were the press and mill, crucial elements in the operation of the complex.

Gabrielli also points out that Dürer accurately captured two elements that reveal the castle’s variety of functions. The first is the wall septum orthogonal to the scaled facade, visible beyond the rectilinear crenellated curtain wall. Unlike today’s situation, no roof pitch is visible beyond that wall, showing that the roof level was lower at the time, indicating that the room above the bishops’ hall was only an attic. The second element is a large rotating wooden trellis, hinged on the scaled facade, with a rope running down to the attic window. The same trellis also appears with hanging load in the Pupila Augusta. Sixteenth-century documents confirm that the revolving wooden trellis captured by Dürer on the Castelvecchio’s scalar façade corresponded to the “falchon da tirar suso la biava,” or a crane used to lift grains and foodstuffs into the attic space. This space called granaro was intended exclusively for the storage of food reserves and had a purely utilitarian function. It was only after 1535, with the transfer of the granary to another location and at the initiative of Prince-Bishop Bernardo Cles, that the top floor of Castelvecchio could be transformed into a representative area. This transformation was part of a larger project to reorganize the castle’s public and private spaces. However, in Dürer’s time, the top floor was still used for practical purposes, justifying the presence of the wooden trellis on the main facade of the castle. In addition to this reading of the image, Gabrielli was also able, thanks to designations taken from inventories, to extract information about the ancient topography of Buonconsiglio: on the right, in the distance, one can recognize the Aquila tower with its four-pitch roof and overhangs that facilitated the residential use of the rooms on the top floor. Despite the distance, Dürer accurately depicts the large cross window of the first-floor room and hints at the one on the second floor, corresponding to the Hall of the Months. The tower was located above one of the city gates, thus explaining the presence of the crenellated wall that protected the large ground-level archway.

The high wall that connected the tower to the Buonconsiglio, known in the 15th century as the “Eagle Wall,” is depicted by Dürer with the crenellated patrol walkway, uncovered and interspersed with sentry boxes. This walkway was later enclosed, covered and adorned with painted friezes by the Cles initiative. However, the two towers that stood astride the wall are missing: one was completely incorporated into the Magno Palazzo, while the Hawk Tower still stands. At the foot of the wall, one notices a tree-lined brolo surrounded by a low sloping wall plastered in white, equipped with a small doorway: a space that probably coincides with the “lower garden” that was soon transformed with an embankment for the creation of the new Clesian garden. Beyond the small street, on the far right, a building with wings arranged around a central courtyard can be glimpsed. This building would form, in the mid-16th century, the nucleus of the castle stables, which still exist. As early as 1527, however, the building performed several functions required of a small but well-organized court: it housed stables for horses, donkeys, and dogs, a stable for wagons, and housing for service personnel.

From Dürer’s vantage point, in addition to the elements already described, another building must have been visible: the cylindrical keep built by Prince-Bishop Johannes IV Hinderbach. This keep had been erected as an addition to the roof garden, which included a wine cellar underneath. The 1527 inventory confirms that the keep was not only a defensive or decorative structure, but also housed bath rooms and a hall, which may have been located just inside the tower. The large cylindrical tower still standing today from the Hinderbachian period must also have been visible to Dürer. This is probably aselective and intentional omission made by the artist in the course of the pictorial drafting carried out in the studio, perhaps intended to avoid the overlapping of the tower with the two bastions of the outer enclosure, which would have created difficulties for the observer in reading. According to this reconstruction of its 15th-century physiognomy, Buonconsiglio Castle was thus an interweaving of defensive, residential and recreational functions, similar to the most illustrious European residences of the 15th century.

These views of the Buonconsiglio Castle and the architectural system within the city walls of Trent were later used by Albrecht Dürer in the backgrounds of the drawing of Pupila Augusta (preparatory for a print that was never made) belonging to the Royal Collection and the engraving with St. Anthony the Abbot (on view at the Pinacoteca Tosio Martinengo in Brescia). The first, which takes its name from the inscription that reads upside down on that sort of basket on the right, is a drawing that still has not been fully deciphered: three elderly women in the foreground are noted to be approached by three young women riding a large fish; among the former, the one wearing a winged helmet points to a vessel filled with water. On the right, on the other hand, there are three small putti, two of which are climbing on the basket mentioned bearing the inscription, and another seated one is pointing to a fleeing hare. Regarding the figures, the artist must have constructed his composition from a series of Italian prints, while, as already mentioned, the city in the background would derive from the aforementioned watercolor studies made by Dürer in Trentino territory. The second, on the other hand, features a Saint Anthony the Abbot seated in the foreground and absorbed in reading, with a complex fortified city in the background, in which the castle dominates. Dürer “invented a St. Anthony for a ready-made architectural composition,” Panofsky wrote, to highlight how that landscape derived from his studies from life on views of Trent.

Four works that linked together testify not only to Dürer’s relationship with Italy, beginning with his brief but significant presence in Trentino, but also to the links that were forged in art between Italy and Germany with the birth of the variegated and original Renaissance that developed in that transitional land between 1470 and the 1430s and 1440s.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.