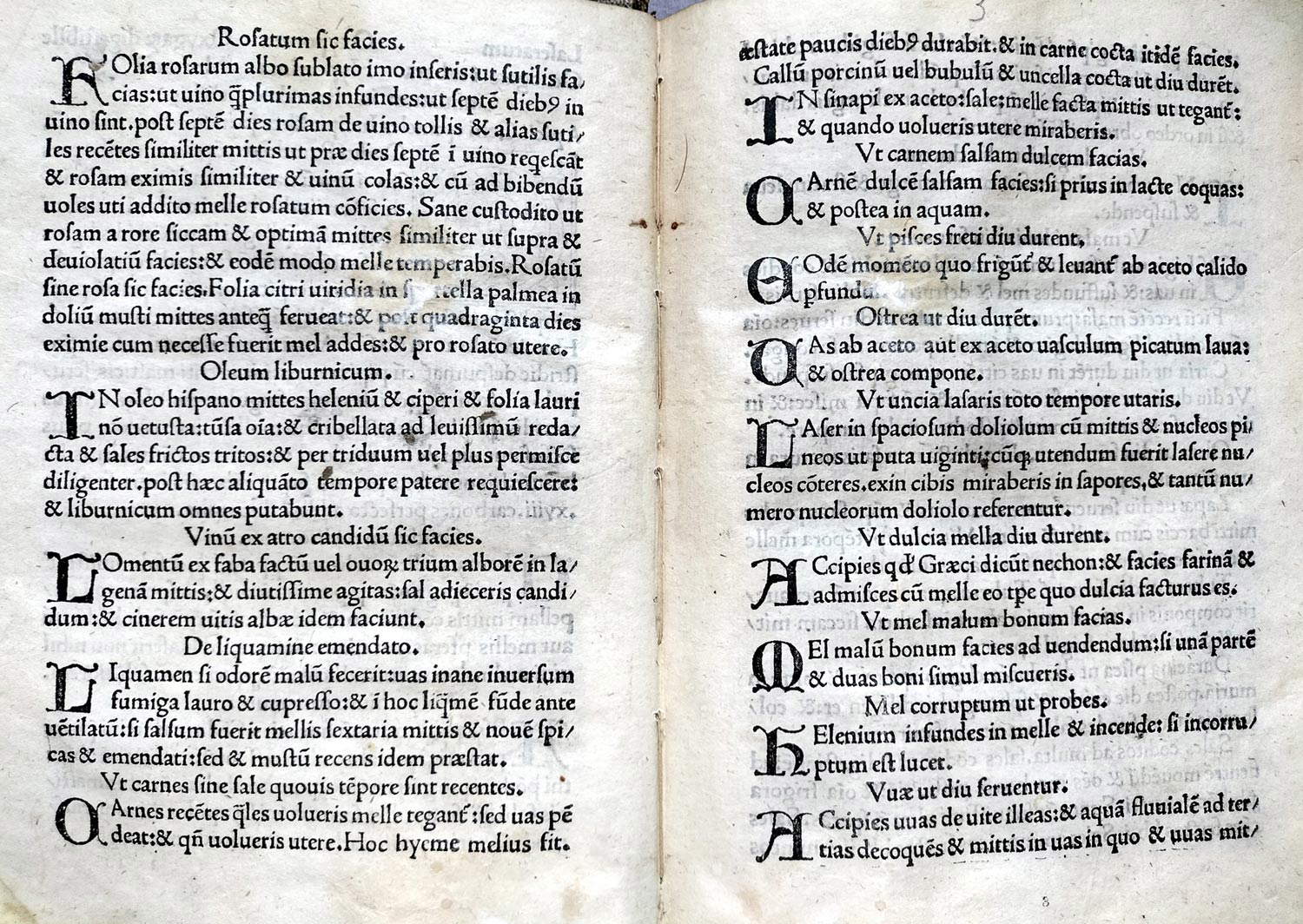

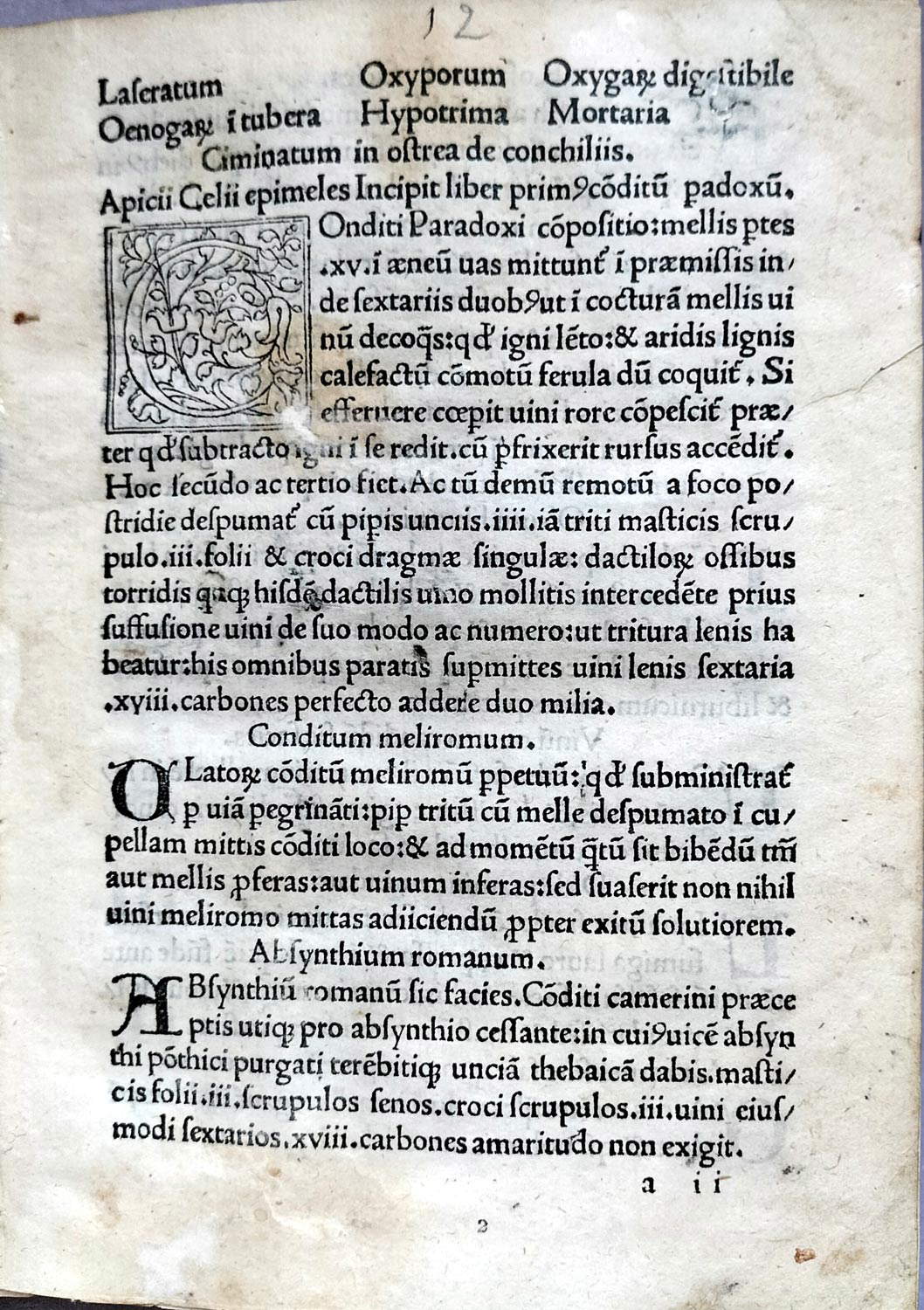

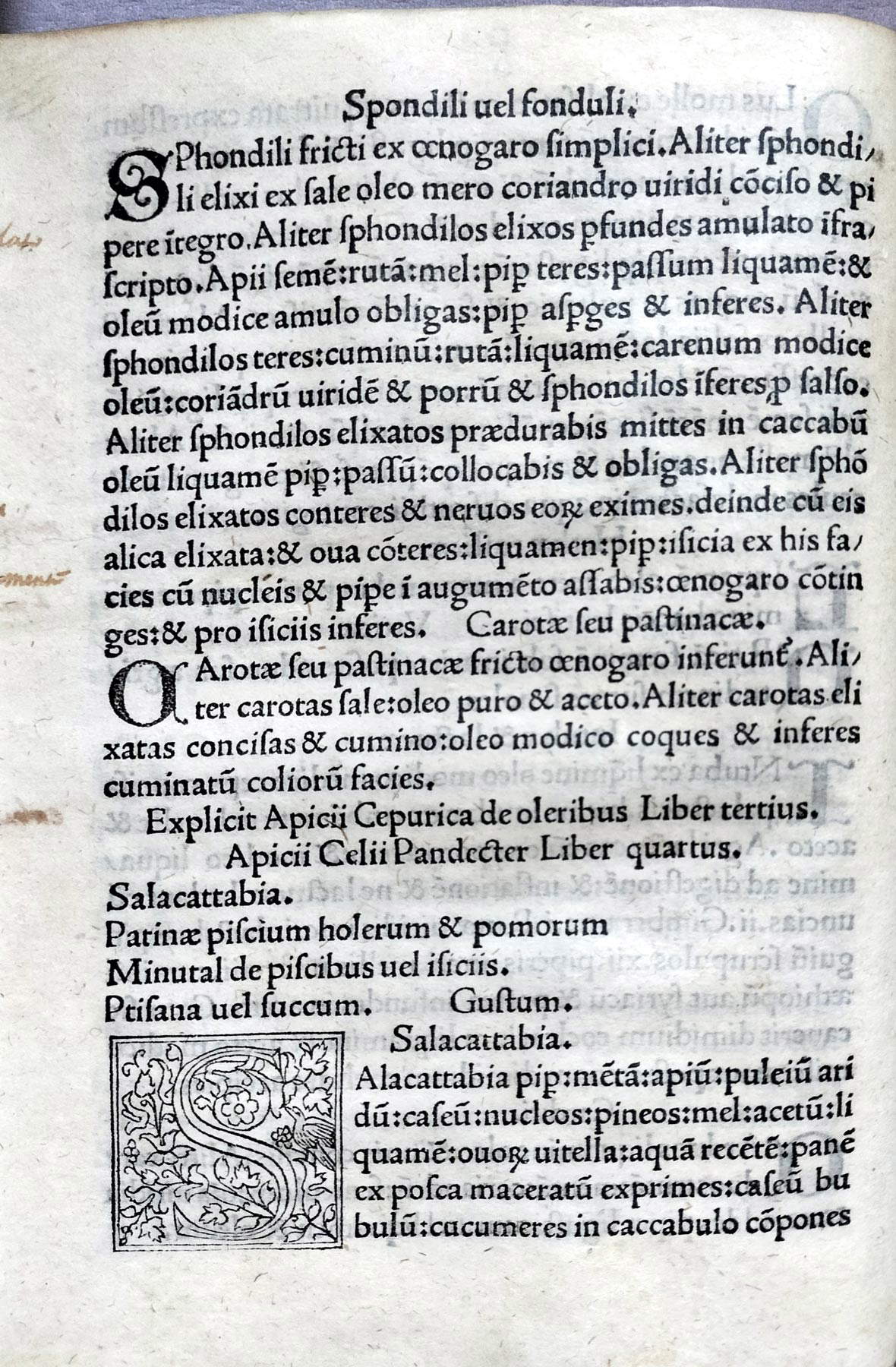

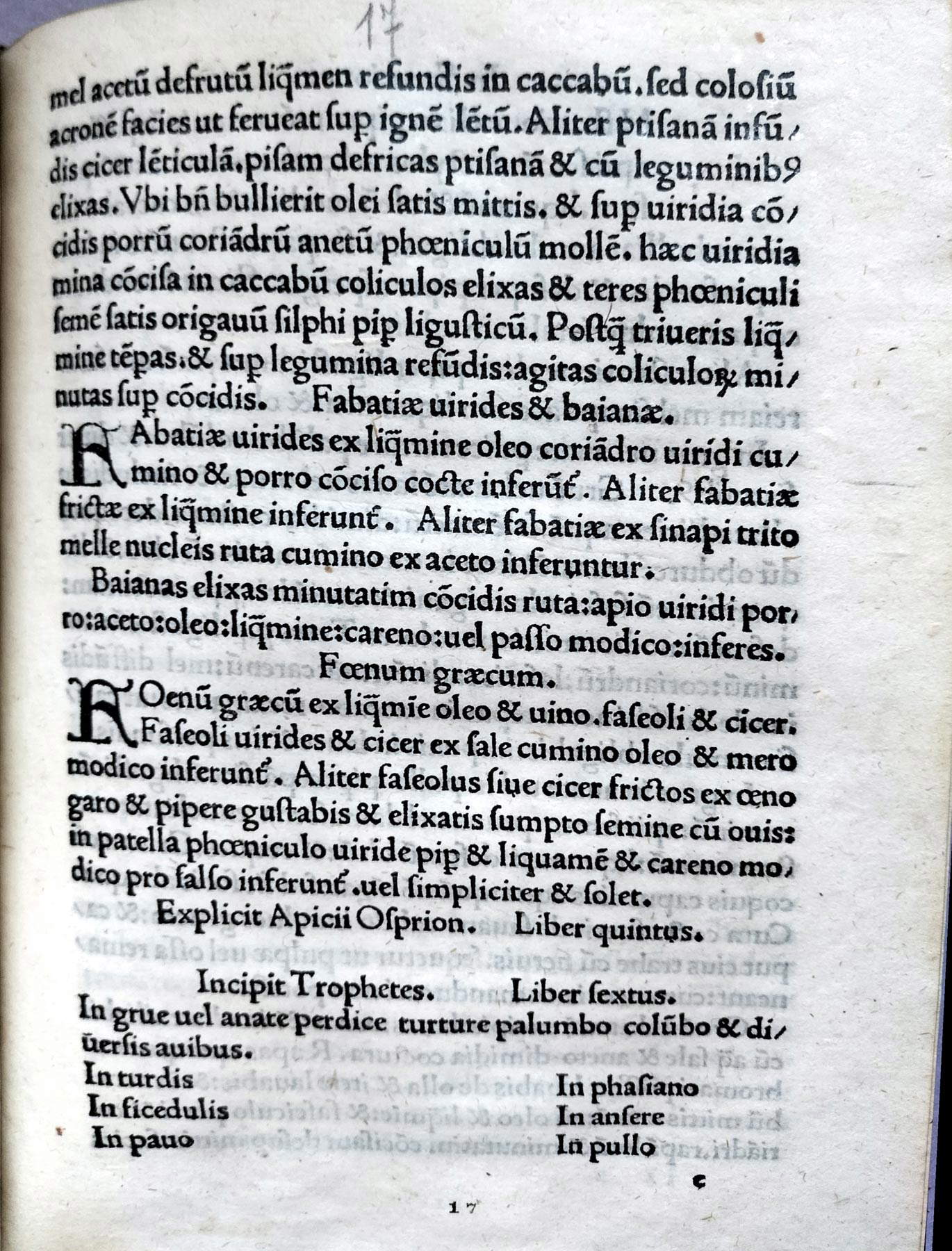

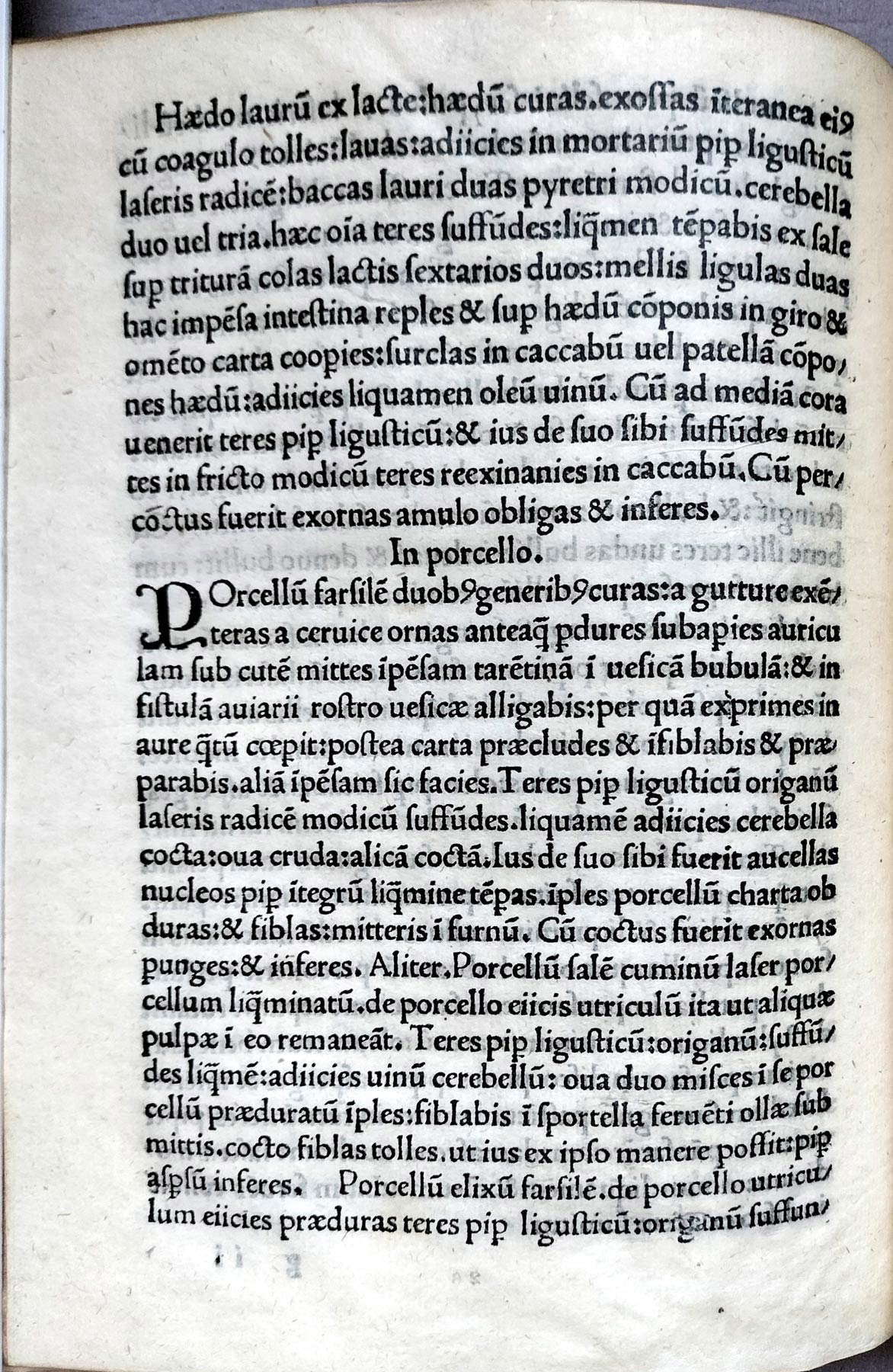

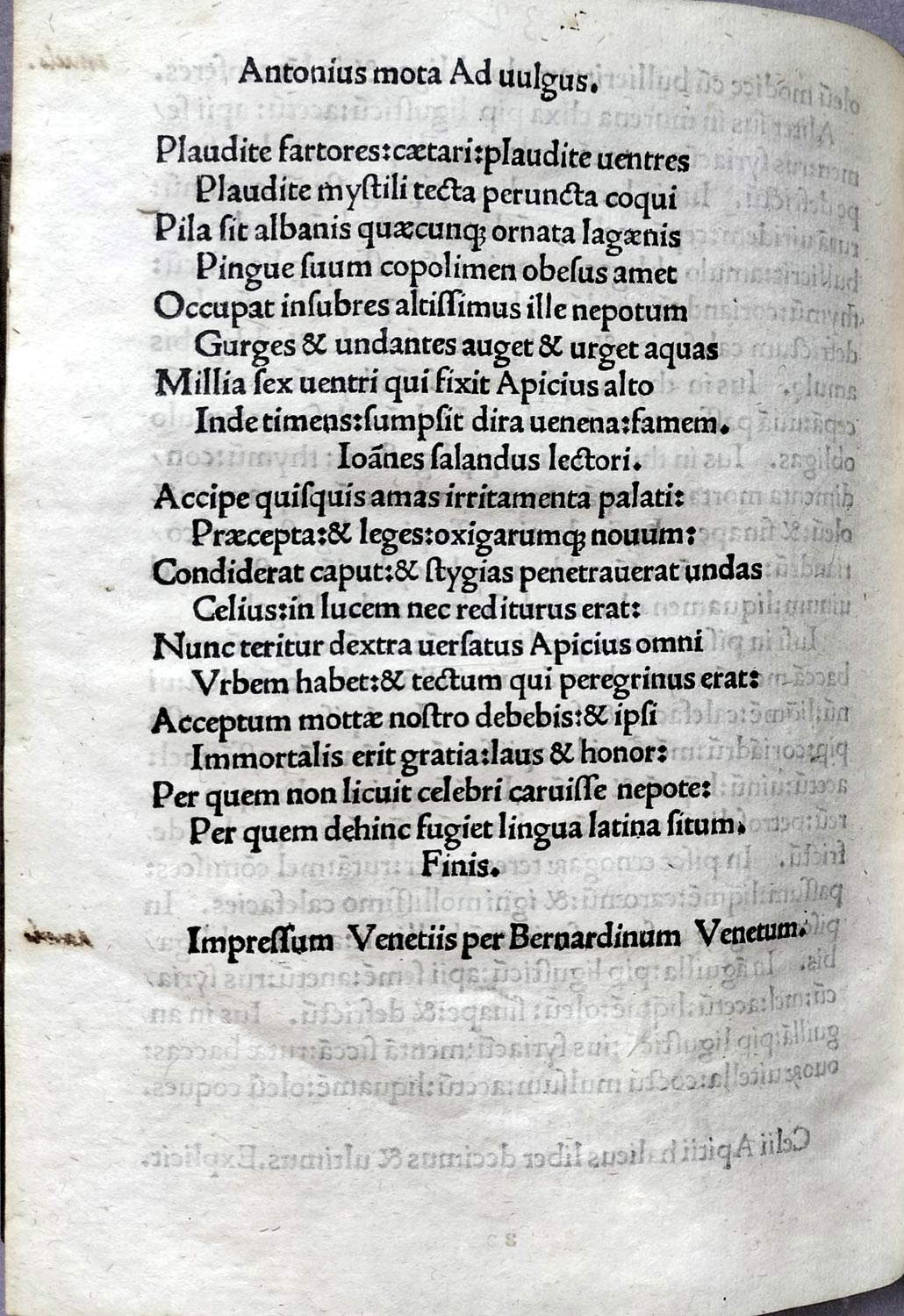

A precious incunabulum printed around 1500 and preserved at the Vallicelliana Library is one of the rare witnesses of the most famous cookbook of antiquity: Apicius’ De re coquinaria. The incunabulum (a term used to indicate a book printed in movable type from the origins of printing until the year 1500) kept by the Vallicelliana is one of the thirteen incunabula of De re coquinaria still present in Italian libraries: it is the editio princeps, or first printed edition of this work, written before printing was invented. Specifically, it was printed in Venice by the Albanian-born printer Bernardino Vitali, who was active in the lagoon between 1493 and 1539, with also a parenthesis in Rome from 1508 to 1522. The Vallicelliana incunabulum has handed down to us the fourth-century Latin vernacular reworking of the original first-century text (which we do not know: the reworking dating from three centuries later is the only way to read De re coquinaria).

Of the author of the work, Apicius, we know only his cognomen, i.e., the last of the three names in Roman onomastics, a kind of nickname acquired during life for a characteristic or event that occurred, and which followed the praenomen, i.e., the personal name given at birth, and the nomen, i.e., the family name(gens), a kind of modern-day surname. “Apicius” was, indeed, the cognomen of the author of De re coquinaria: the most likely guess as to his full name is that he was called Marcus Gavio Apicius. We know nothing about his family origins, nor is there a complete biography of him: all we know is that he lived during the time of Tiberius and that, according to anecdotal evidence about him, he was a lover of luxury, as well as, of course, a connoisseur of Roman cuisine.

How to

How to How to

How to

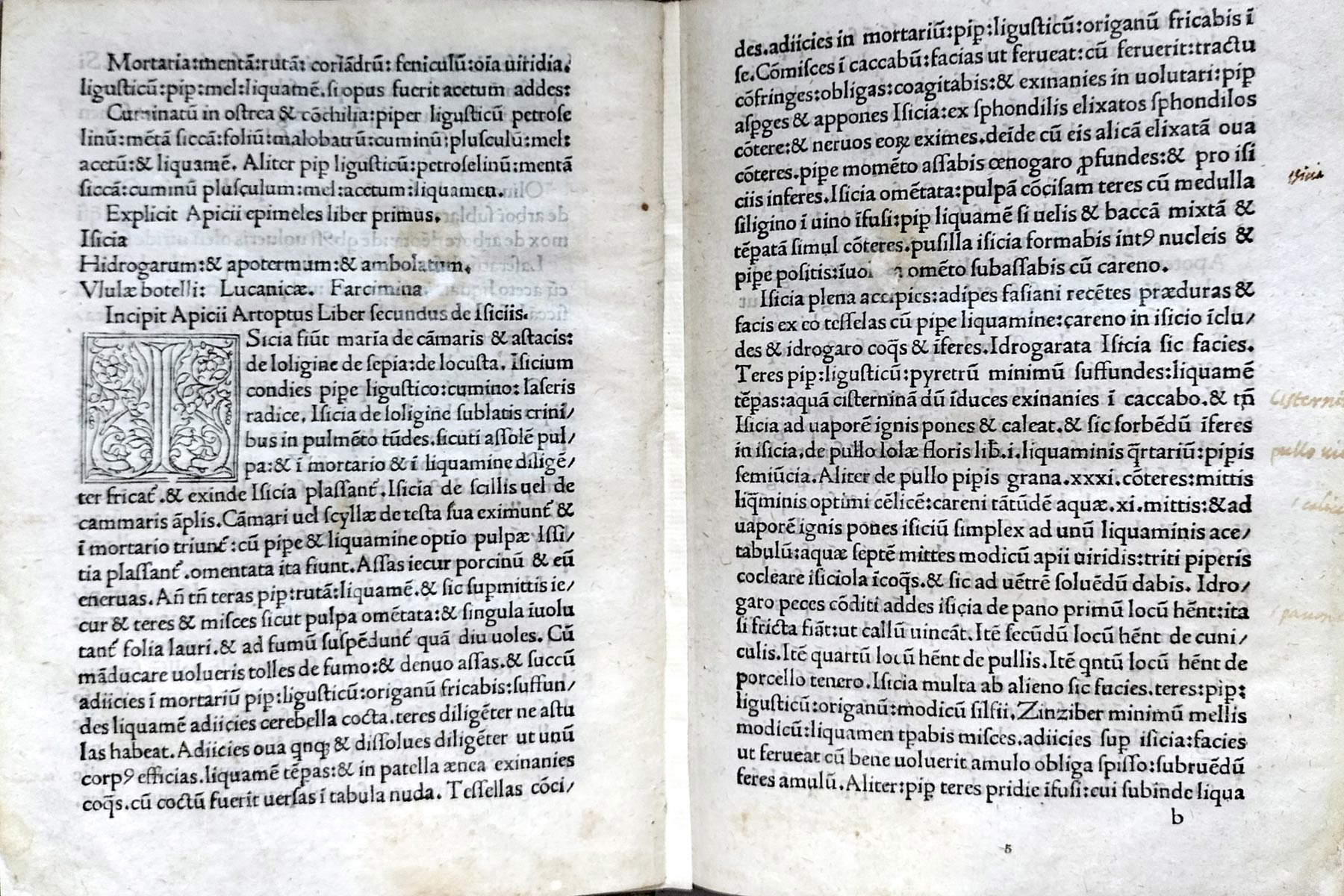

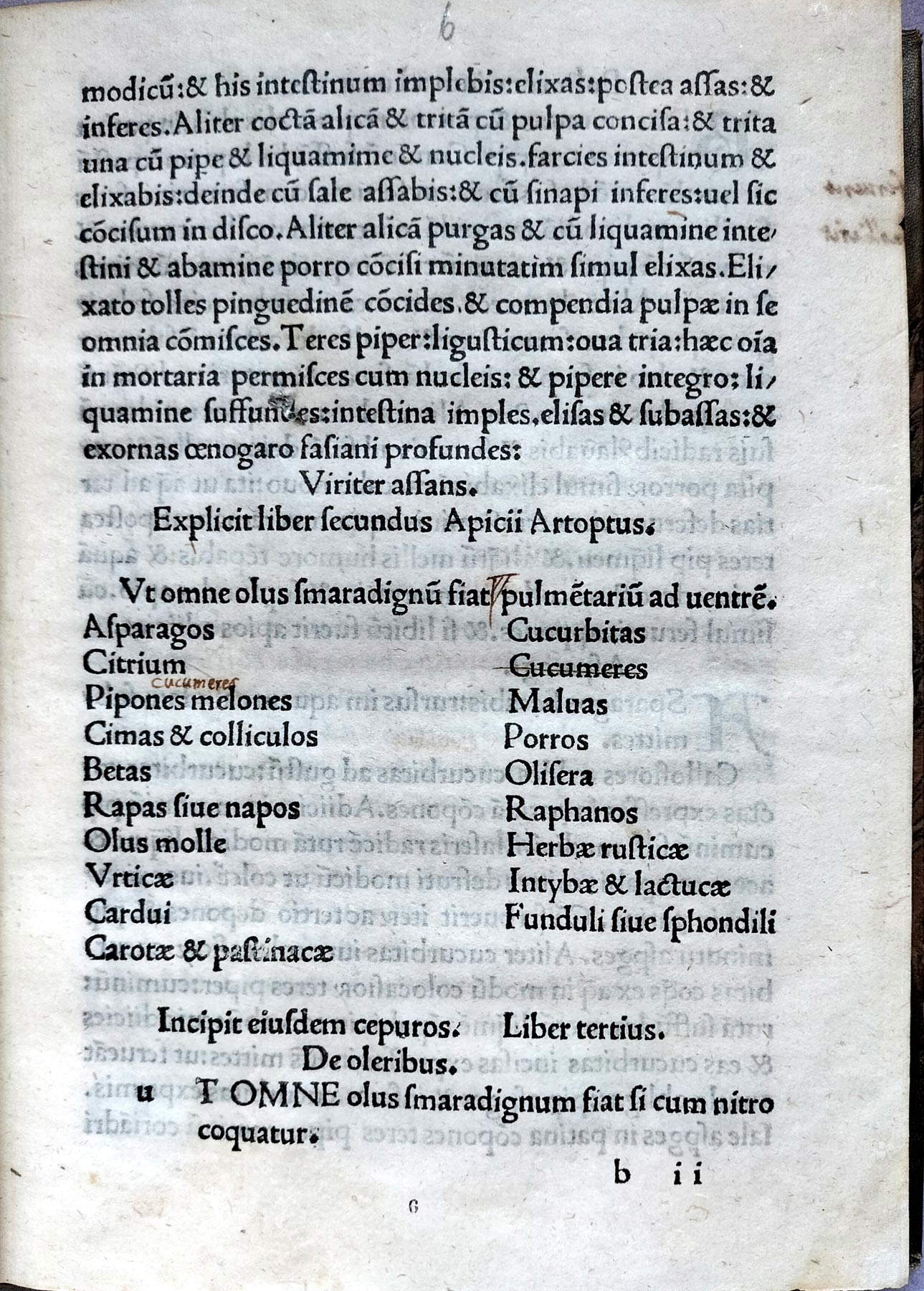

His De re coquinaria gives us an important insight into what was eaten in Roman times, in particular what recipes were most in vogue mostly among the wealthy classes: Apicius’ idea is precisely to provide recipes to the reader by indicating the procedures and quantities of ingredients to arrive at the final result. The work is divided into ten books, with titles in Greek: the first, Epimeles, “the expert in the kitchen,” is a summa of tricks and suggestions that Apicius advises those who want to cook (for example, how to flavor wine, how to make cakes made with honey last a long time, how to preserve grapes, apples, fresh figs, pears, cherries, olives for a long time). This is followed by recipes in the narrow sense in the other nine books: Sarcoptes (minced meats), Cepuros (vegetables), Pandecter (“Pandette,” a list of recipes for what we would today call “one-dish meals”), Ospreon (legumes), Aeropetes (birds), Polyteles (dainty victuals), Tetrapus (quadrupeds), Thalassa (sea, i.e., fish dishes), Halieus (literally “fisherman.” the book contains recipes for sauces with which to season fish).

One becomes aware of the fact that this is a cookbook aimed at the upper classes by the tenor of the creative and sophisticated dishes that appear in Apicius’ work: “in addition to the creation of imaginative dishes featuring the use of ostrich, wild pigeon, crane, francolin and beccafichi,” writes scholar Clotilde Vesco, who also authored the translation of De re coquinaria for Newton’s types, “in Apicius’ book one finds an incredible amount of sophisticated, inviting and tantalizing sauces .... worthy of proof.” His gastronomic treatise, however, also “leaves everyone free of his own inventiveness and-if not in rare exceptional cases-his own taste. Appearing in this work is the true love of cooking that everyone should feel as soon as he approaches the stove.” Apicius, in effect, allows the apprentice cook reader to dose the ingredients as best suits his or her taste (although the author always indicates the quantities he or she feels are correct), or to launch into variations, for example by adding something if after tasting the recipe the reader who has tried repeating it would like to modify the original.

The book is all written in the second person singular: Apicius is addressing his reader directly. Some recipes have remained virtually unchanged since then: such is the case with the Isicia (which Vesco translates as “meatballs”). “Those marine ones,” the author writes in the second book of De re coquinaria, “are made of lobsters, shrimp, squid, cuttlefish, and freshwater crayfish. You will season the meatball with pepper, ligustic, cumin and laser root” ( laser, also known as silphium, was a plant, now extinct, that grew in Roman times in Cyrenaica: of the apiaceae family, it resembled fennel). Not far from our taste is also the recipe for baked wild boar: “mince some pepper, ligustic, oregano, pitted myrtle berries, coriander, onion; bathe with honey, with wine, with sauce, with a little oil, heated, bind with starch. Pour over baked boar.” And the same can be said for dishes with squid or octopus in a pan, which involve cooking to the right point and adding a few simple seasonings (for squid, pepper, rue, a little honey, cooked sweet wine and a few drops of oil, while for octopus, pepper, sauce and laser). The term “sauce” refers (following Vesco’s translation) to a particular condiment that Apicius called liquamen: it was made from minced fish entrails, which were then cooked in a pan together with pieces of fish and then left to ferment. This produced a sauce that was usually bought ready-made: the closest modern-day counterpart can be found in the colatura di alici typical of Cetara. In De re coquinaria the sauce is used in a very large number of recipes, even on dishes that are not fish-based.

Most of the recipes, however, are far removed from what we are used to today. Roman cuisine, meanwhile, included abundant use of spices, used to season even the most unthinkable foods. Melons, for example, which were flavored with pepper, honey, vinegar, and silphium, or watermelons (here is the recipe for boiled watermelons: “You will boil peeled watermelons with already blanched brains, cumin, and a little honey, or with celery seeds, sauce, and oil. You will condense with starch, sprinkle with pepper and bring to the table.”). Or the fried anchovies, which Apicius suggests seasoning with sauce and pepper, or the “pear dish”: “mince some boiled and cored pears together with pepper, cumin, honey, passito, sauce and a little oil. Add to the eggs fan a pan, sprinkle with pepper and bring to the table.”

Then there are recipes that involve mixtures of ingredients even far apart, with results that would seem disgusting to us today. This is the case with the “Apician minute”: “cook everything together oil, sauce, wine, heads of leeks, mint, fish, small sausages, capon testicles, glands of lattonzoli. Mince some pepper, sprinkle with sauce, add little honey and the gravy from the pan, add wine and honey. Let it boil. When it boils, break off a sheet of dough and let it thicken, stirring well. Sprinkle with pepper and serve.” Or of the "ortolano pig, " a pig stuffed with chicken, thrushes, sausages, dates, assorted vegetables, to be roasted and then seasoned with sauce, honey, oil. And again, stuffed hare, which actually involves a procedure for making a double filling: “whole pine nuts, almonds, chopped walnuts or acorns, hard peppercorns, meat of the same hare. Mix it all together with crushed eggs, then wrap it in a pork net and roast it in the oven. Thus make a second stuffing: rue, enough pepper, onion, savory, dates, sauce, cooked sweet wine or must. Boil it for a long time until it becomes thick and so you will use it. But cook the hare first in the sauce with ginger and laser.” There are also many recipes for stuffing or seasoning chicken in various ways. There are also recipes for desserts in the book on delicacies. They have no particular names (they are all identified with the formula Aliter dulcia, “other sweets”), and they are all honey-based. There is, for example, a celery-based dessert: “scrape beautiful celery and put it in milk. When they have soaked put them in the oven so that they do not dry out. Remove them hot and sprinkle with honey, prick them so that they soak. Sprinkle with pepper and serve.” And then another puff pastry: “chop pepper, pine nuts, honey, rue and mix with passito. Cook in milk and with a sheet of bread. Cook when everything has set with a few eggs. Bathe in honey and bring to the table covered with pepper.”

Finally, there are several dishes with ingredients that are no longer used in cooking today. This is the case with the crane, cooked with a side of turnips, or boiled and seasoned with a dip made of pepper, cumin, coriander, mint, oregano, pine nuts, carrot, sauce, oil, honey, mustard and wine. We don’t even eat flamingos anymore, which Apicius suggests boiling in a pot with leeks and cilantro added halfway through cooking and cooked must at the end, then sprinkling with a pesto made of pepper, cumin, coriander, silphium, mint, and the flamingo’s own gravy. A dish much loved by the Romans was then the stuffed dormouse: the small rodent had to be stuffed, we read in De re coquinaria, with pork sausages, pepper, pine nuts, silphium and the ever-present sauce. Among the delicacies, in addition to roasts, cakes, ham, kidney, chops, eggs, and other dishes that might sound more familiar, Apicius also includes colocasia, a plant grown today mostly for ornamental purposes, and of which Apicius suggests boiling the bulb and then seasoning it with pepper, cumin, rue, honey, sauce and oil (today the custom of eating colocasia has been maintained, in the territories once controlled by Rome, only in Cyprus).

The De re coquinaria is not the only source for learning about Roman cuisine: also at the Vallicelliana there is a manuscript codex, E39, which contains the De re rustica, a book of advice and recipes by Lucius Junius Moderatus Columella, a military man who, at the end of his career, devoted himself to agriculture and, indeed, to cooking. This is a valuable codex probably made in Florence in the mid-15th century: along with De re coquinaria, it is one of the most useful treatises for knowing what was on the tables of the Romans. And it is interesting that two of the oldest witnesses to these treatises are preserved in the same library.

The Vallicelliana Library in Rome originated in 1581 with the testamentary bequest of the Portuguese humanist Achille Stazio (Aquiles Estaço), who left his book heritage, consisting of 1.700 printed volumes and 300 manuscripts, to the Congregation of the Oratory, which had been united since 1551 around Filippo Neri and to which in 1575 the church of Santa Maria in Vallicella, hence the name of the Library, had been donated by Pope Gregory XIII (who officially recognized the society of Oratorians that same year). The collection left by Achille Stazio was joined by the books of Filippo Neri, which passed to the Congregation in 1595. Soon the Vallicelliana Library was enriched with other funds: the Archives and part of the Library of San Giovanni in Venere (1585), the library of Cardinal Silvio Antoniano, the books of Pierre Morin and Juvenal Ancina, the manuscripts that arrived from the Abbey of Sant’Eutizio in Norcia, the collection of Father Gallonio, the first biographer of Filippo Neri, and then again part of the book collection of Cesare Baronio. Already in the early seventeenth century, therefore, the Library had reached considerable proportions. In the following centuries it was first looted during the French occupation of Rome in 1797-1799, then in 1874, following the laws on the suppression of religious corporations, the Vallicelliana became a public law library. In 1883 in some of the library’s premises found a home for the Società Romana di Storia Patria, established in 1876 and still housed in the Vallicelliana. Today the Vallicelliana Library, after having been administered for a long time by the Ministry of Education, is an institute of the Ministry of Culture.

The institute currently has a holdings of about 130,000 volumes including manuscripts, incunabula, printed volumes and music. These are mostly works with historical-ecclesiastical and theological themes, but there are also books on philosophy (including many ancient commentators on Aristotle), law, botany, astronomy, architecture and medicine. Among the library’s most valuable items are the 9th-century Alcuin Bible (ms. B 6), a 12th-century illuminated Greek Gospel Book (ms. B 133), and a valuable 16th-century Book of Hours (ms. A 45), which are among the approximately 3,000 manuscripts. Then again, among the ancient printed collection (about 40.000 volumes, mostly kept in the Borromini Hall) is the collection of the 372 works that belonged to Filippo Neri kept in the Libraria (ancient wooden scanshelf commissioned in 1662 by Cesare Mazzei), the notices, edicts, and printed notices datable between the 16th and 19th centuries, mostly issued by the Papal States or dating from the Napoleonic period in Italy, the Vincenzo Badalocchi fund consisting of over five hundred printed editions on scientific and astronomical subjects and thirteen manuscripts. Still, the Library has a collection of 1230 engravings acquired mostly in recent years, with also some pieces from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and the important music collection, an important testimony to the repertoire of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Also present is a photographic archive with about 12,500 photographs, formed in the last two decades: there are mainly images of cities, archaeological sites, Italian and European localities, and photographs bearing witness to Italian history of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.