What are the trends in young contemporary painting today? A quick overview

Those who are used to flipping through art magazines know that art magazines like to offer their audiences looks and analysis in the form of rankings. The ten best booths at the fair, the twenty artists to watch out for, the thirty exhibitions of the year, the hundred most influential personalities in the art world, and so on. Rankings have the unquestionable advantage of being immediate, easily understood, captivating to the public, capable of provoking long and often heated discussions, and for the writer they are also relatively easy to compile since they take much less time than a broader spectrum analysis. For the past few years, in art magazines, especially those of the Anglo-Saxon area (but also in the more art-conscious generalist press), it has become increasingly common to come across lists of the works that, in the opinion of those composing them, should best represent the art of the 21st century. It is difficult to find rankings that agree on names, works and positions, although some artists are recurring and although one can actually find one element that brings everyone together: the sparse presence of painting. In the Artnet News best of (September 2017) only one painting appeared out of some 20 works mentioned. The Guardian ’s (2019) featured two painters out of 25 artists. And in the top forty works in Artnews ’ recent top 100 (March 2025), there are only three paintings. This, however, does not mean that painting is not a language still capable of being alive, pulsating, surprising, spoken everywhere, although it may appear (and probably is) a medium with a hopelessly vintage flavor, to put it mildly. Today, a painter is much like a poet. That is, a figure who practices a language far removed from the sensibilities of most. Yet alive.

And it is a living language for so many reasons. First, because it has a long history and painters are, after all, repositories of a tradition that runs through the centuries. Then, Jonathan Jones wrote in the Guardian a few years ago, because painting “works wherever you put it: from the National Gallery to an Ice Age cave to the wall of a pizzeria, it is simply paint used by a human being to leave meaningful marks. That’s why painting is everywhere, because it can go anywhere and still be a type of art.” Again, painting is still widely used as a means of reflection on the present and the future, because it is one of the most immediate tools available to human beings should they be interested in offering their fellow human beings a reasoning that wants to transcend phenomenal reality and investigate the fantastic, the unknown, the dream, the surreal, the intangible. And then, trivially, because in our living room it comes back easier to hang a painting than an installation of pipes and rubble or an environmental video: painting is more immediate because it is more transversal. As a result, the market values painting, and paintings produced by contemporary artists are still sold at significant prices. Then, of course, painting today is but one of the many tools art has at its disposal, which is why, having to cope with so much proliferation of expressive media, it would seem to have lost relevance. And in a sense it has: the visual arts are no longer the dominant arts of our time, and painting, the rankings mentioned above show, is not dominant among the visual arts. However, painting is still a tool widely used by artists around the world. Therefore, it is not a stationary medium of expression. Far from it: exploring the painting scene at the turn of the quarter-century is useful for understanding what is happening to painting, what transformations this medium is undergoing, what trends young contemporary painting is going through. A task, admittedly, difficult: rankings are a widespread medium also because it is not easy to try to look at the present with detachment. But it is worth a try, with no claim to exhaustiveness. And with the awareness that today the degree of innovativeness in painting seems to be in decline. In the lines that follow, and which concern artists born since the 1980s, one will not find bombastic names. Names that everyone knows. Names well known even outside the narrow circle of insiders. This is because, first of all, painting, no longer being a dominant art, has lost much of its subversive power, its explosive charge, its ability to dictate the rules of modernity. And then it has gone out of our habits, it has ceased to be relevant to the lives of most people, it is not part of our everyday life. Or at least it is not part of it in the way that, on the contrary, a film, a song, or even a public art intervention can be part of it (which is why today’s laymen are much more familiar with sculptors or urban artists, so-called street artists, than easel painters).

Keeping this situation in mind, then, one could begin with an indisputable fact: in the last decade, the scenario has been heavily modified by globalization and, perhaps even more significantly, by the interconnectedness provided by the Internet, with all its most recent consequences. Above all, the extreme speed with which information travels and the ease of access to content: until the early 2010s, roughly speaking, that is, before the Internet moved towards the dominance ofuser-generated content (user generated content) and the ease of exchange ensured by social networks, to know vertically the art scene of another country, it was necessary to do research, study in depth and travel. Instead, today it is enough to waste some time on Instagram, on art fair websites (all major fairs make available catalogs of works), inside the viewing rooms of galleries. A sculptor in Florence can have some knowledge of what his colleagues are doing in Stockholm, a painter in Nice can find out what is happening in New York without moving from his home, a gallery owner in Hamburg can get information about artists exhibiting at a Cape Town fair. The transformations of the net have thus accelerated and further reshuffled the multiculturalism that globalization has left us as a dowry, which has helped to detach artists more and more from the constraints of national or regional artistic traditions: the main consequence is that much of 21st-century painting is, we might say, cosmopolitan painting. Young painters draw from different traditions, contaminate, mix elements that come from cultures far from those in which they grew up, sometimes even unconsciously. Young painters tend to address global issues (the climate crisis, economic crises, human rights, civil claims, migration, technology, and so on). Artists such as Salman Toor (1983), who among painters born after 1980 is one of the most interesting, or Njideka Akunyili Crosby (1983), or even Jamian Juliano-Villani (1987) move in this groove. Conversely, overabundance leads to overload, with the consequence that the multiculturalism fostered by the accessibility of networks makes painting in the 21st century increasingly homogenized: it becomes increasingly difficult to understand the origin of an artist, although there is no shortage of exceptions. On the contrary: the artist who succeeds in marking his painting with a strong imprint, which brings out his own tradition within a research that looks elsewhere, tends to gain more consideration, because he refuses homologation and imitation. One can explain in these terms, for example, the fact that African painting is held in the highest esteem by both critics and collectors: it happens because none of the most significant African artists renounce their own cultural background. A few names: Amoako Boafo (1984), Emmanuel Taku (1986), Oluwole Omofemi (1988), Tafadzwa Tega (1985). One might be accused of wanting to glorify exoticism, but in the case it would concern any artist, from any background (even an Italian, say, is exotic to an American collector): in a market that has become global, the collector rewards the painter who has, on the one hand, matured a recognizable stylistic figure and, on the other hand, is able to escape from homologation, and from homologation one moves away only through the mediation of tradition. A few examples of painters born after 1980 who seem to have taken this path well (non-exhaustive examples, but it must be said that the shortlist cannot be enlarged much since one struggles to find interesting personalities): in France, Claire Tabouret (1981), Djabril Boukhenaïssi (1993); in Belgium, Ben Sledsens (1991); in Italy, Francesca Banchelli (1981), Rudy Cremonini (1981), Andrea Fontanari (1996), Marco Salvetti (1983); in England, Michael Armitage (1984); in Switzerland, Rebekka Steiger (1993); in Mexico, Ana Segovia (1991), Felipe Baeza (1987); in Japan, Etsu Egami (1994), Ayako Rokkaku (1982).

This cosmopolitan painting, which fishes from traditional aesthetics to respond to the present, finds its own distinctive feature in a cultural nomadism that, in the history of art, is unprecedented: the new painters do not belong to a single tradition but draw their references from often distant pasts. Salman Toor, for example, draws from the history of European art (particularly Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art), and mixes it with memories of his homeland, Pakistan, to offer the relative an account of his own experience as an immigrant in the United States who moves among nightclubs, who hangs out with other Asians living on the fringes of American metropolises, who locks himself in a weekday intimacy to try to stave off his own existential malaise. In contrast, Njideka Akunyili Crosby blends Western iconographies with African motifs to produce art that, by her own admission, tries to think of both Nigerian (her homeland) and American (where she lives) audiences. In Italy, Andrea Fontanari combines an attitude indebted to American contemporary realism with an insistence on objects that is instead typical of postwar Italian art, from Guttuso to Ferroni, from Gnoli to the Scuola di Piazza del Popolo. Some of the characteristics of the contemporary cosmopolitan painters could be associated with the concept of “altermodern” elaborated in 2009 by Nicholas Bourriaud, to indicate an attitude that seeks to overcome the relativism of postmodernism, that operates in globality while rejecting standardization, that combines past, present and future with new linearity. The altermodernist according to Bourriaud’s formula, however, prefers nonlinear and open narrative structures, and is interested in process rather than content, in the way elements are related rather than in the intrinsic meaning of each element, because the altermodern work can be seen as a node in a network of connections. The altermodern, we read in the presentation of a Tate exhibition that, also in 2009, had been devoted to this concept (leaving it to the public, however, to decide what “being modern today” meant), “privileges dynamic processes and forms over one-dimensional single objects and trajectories over static masses.” In Italy, trying to elaborate an altermodern formula in painting was the art-critical collective Luca Rossi, which sees in Enrico Morsiani (1981) its “frontman,” with the series IMG, paintings linked to the project If you don’t understand something search for it on Youtube, a’work-in-progress that refers to amateur videos uploaded to YouTube to elevate a kind of ode to the chaos of digital content and in particular to forgotten content, to those uploaded to the web at the dawn of the social era and then gone into oblivion. On the other hand, none of the cosmopolitan painters mentioned above can be called altermodern, at least according to Bourriaud’s meaning, since in their practice the content is strong, the processes are traditional, and there is no focus on dynamic structures and trajectories. In any case, compared to the fragmentation and citationism that has characterized postmodern painting, contemporary cosmopolitan painters, on the contrary, attempt a coherent synthesis and, while sometimes retaining a certain irony that was also characteristic of postmodernism, seem to oppose the deconstruction, sarcasm, and eclecticism that characterized the art of previous generations, and on the contrary mix languages and traditions to create new narratives, which usually have to do with major contemporary issues: social claims, environmental crises, migration, often with personal and autobiographical approaches but trying to speak to a global audience (a reason why the new cosmopolitan painters seem more immediate, even easier, than painters of previous generations).

A lunge into the main narratives that characterize young contemporary cosmopolitan painting is needed at this point, since they are yes complex, diverse, and interconnected, but they are also recurrent and aim to reflect on the dynamics of a complex international and global situation marked by major political, social, cultural, and economic transformations (post-colonialism and the resulting power relations, racial and social inequalities, digitization and the increasing use of technology, gender issues, cultural interconnectedness, migration and environmental crises). Thus, the young cosmopolitan painter tends to be an engagé artist. Cosmopolitan painting in the 21st century, meanwhile, often insists on the concept of “identity,” seeking to understand how migrations, cultural connections, transnational ties, and the fluidity of contemporary societies, primarily Western societies, are reflected on individuals and communities: the work of the aforementioned Nijdeka Akunyili Crosby, noted above, investigates the intersections between Nigerian and American cultures. Salman Toor’s seeks to tell the story of the diaspora experience. Many painters, on the other hand, seek to tell stories of resistance and struggle for self-determination of peoples who have suffered the effects of colonialism or of communities that have long suffered racial segregation. For the sake of brevity, since there are so many artists addressing these issues today, we will limit ourselves to making quick mention of the U.S. scene associated with a painting that, for just under a century now, has never ceased to tell the story of the African diaspora, from Jacob Lawrence’s pioneering experiences with his 1940s migration scenes through theHarlem Renaissance and the art of the 1970s born in the wake of the struggles of the Civil Rights Movement (Barkley Hendricks, Faith Ringgold) to Basquiat’s graffiti art and the works of artists born between the 1960s and 1970s who chronicled the complexity of African American culture (Kerry James Marshall, Mickalene Thomas, Kara Walker, Kehinde Wiley). Young and cosmopolitan artists who stand as heirs to this significant tradition may be considered, for example, Nina Chanel Abney (1982), Tajh Rust (1989), Ambrose Rhapsody Murray (1996), Shaina McCoy (1993), Na’ye Perez (1992), Crosby herself.

There is also research on gender and queerness carried out by artists who continually question sexual identities, gender roles, and body representations themselves, with painting being used as a means of expressing personal and collective experiences that reflect on the evolution of queer culture and the public space of self-expression of one’s gender identity. Artists such as Salman Toor, Tschabalala Self (1990), Jonathan Lyndon Chase (1989), Frieda Toranzo Jaeger (1988), and Anthony Cudahy (1989) can be framed in this context. On the other hand, painters such as Madjeen Isaac (1996), Claire Sherman (1981), Zaria Forman (1982), and Ranny MacDonald (1994) work on the climate change front, while the roster of artists interested in social critique (of capitalism, economic systems, systems of power, the overwhelming power of technology, and so on) could include Jamian Juliano-Villani, Chloe Wise (1990), Vladimir Kartashov (1997). Then there are artists who investigate themes related to the female body, to femininity, often reflecting on the body as a territory of claim, if not as a space tout court. Mention can be made here of artists such as Christina Quarles (1985), Sahara Longe (1994), and Alejandra Hernández (1989), while for Italy it is possible to mention Romina Bassu (1982), Chiara Enzo (1989) and Giuditta Branconi (1998) .

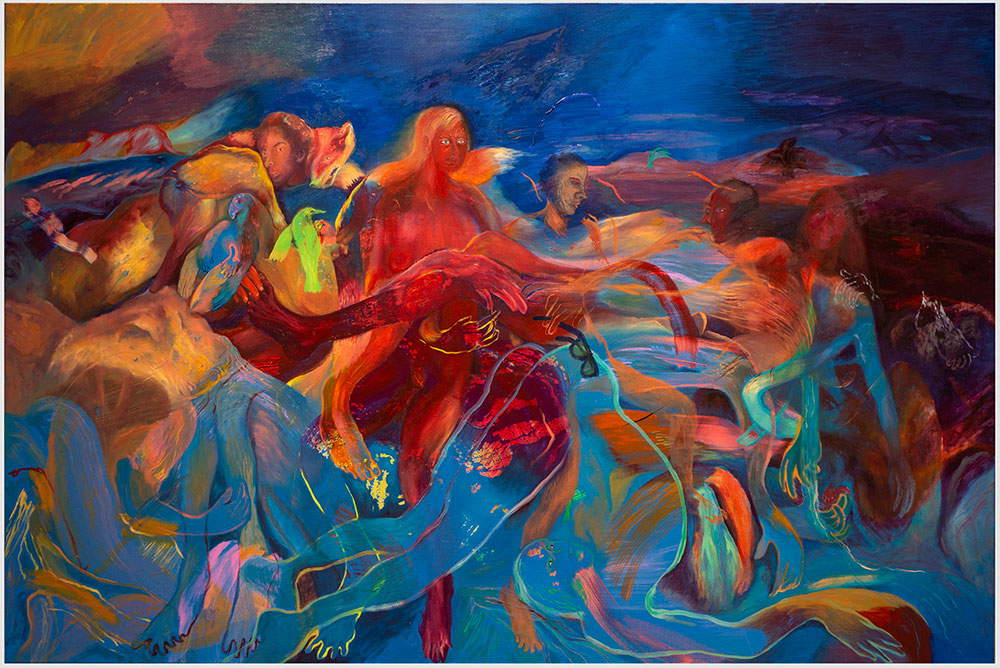

Outside of the art engagée one then finds another, no less interesting (indeed, often much more original, innovative, and even better able to describe the present), characterized by a marked tendency towards intimism, a refuge in the everyday that is at the center of the practice of many young contemporary painters. This refuge in the everyday is a response that many oppose to the challenges posed by today’s world: what emerges is a painting that finds refreshment in the domestic dimension, in affections, in the everyday, and that looks to memory, time, love, friendship as spaces of resistance, contemplation, and redefinition of reality. An art that speaks of intimate, human connections, an art that rejects the political instance (or at least the active political stance) but is nonetheless no less political than the more directly engaged. An art that also often finds refuge in dreams and then takes on dreamlike connotations. Artists such as Jordan Casteel (1989), Caroline Walker (1982) and Andrea Fontanari are those who perhaps best offer an example of this kind. On the other hand, to have a couple of examples of artists interested instead in an investigation that goes beyond the plane of the rational and instead enters the territories of the dream, the unconscious, and the subliminal, one can look at the works of Francesca Banchelli, whose recent research delves into a visionary dreamlike expressionism that renews the tradition of Transavantgarde, or those of Alessandro Fogo (1992).

Returning instead to the strictly formal level, and always moving away from the more politically committed narratives, we can end the overview with the research of abstractionists working within the framework of young cosmopolitan painting: it is difficult to find original investigations here, in a field in which it is really hard to innovate, but there are those who try nonetheless. For example, there are those who try the route of working on materials like Julia Bland (1986) and those who instead reinterpret modern abstractionism by looking at space like the Italian Erik Saglia (1989), and then, while not particularly innovative, for consistency of their research and quality of their work should be mentioned at least Emma McIntyre (1990), who draws, more or less consciously, from Richter and abstract expressionism and especially that of Helen Frankenthaler, and Jadé Fadojutimi (1993), for whom it is instead difficult not to think of Julie Mehretu. Still speaking of abstract art, critic and artist Julien Delagrange, editor of the Belgian magazine Contemporary Art Issue, wanted to identify a trend in contemporary abstractionism, namely the interest in the gradient, a motif he considers ubiquitous in today’s visual culture, from graphic design to webdesign, from printmaking toall the way to artists-from-Instagram, those suggested by algorithm filters, not infrequently abstractionists who express themselves by means of the gradient and who through that medium, Delagrange says, often manage to go viral because the gradient is popular and the public seems to like it. In his view, this interest is based on a particular sensory response, “a physical and psychological experience that combines pleasant and relaxing sensations in response to viewing a gradient.” A kind of visual ASMR, for Delagrange. Nothing particularly new, since great twentieth-century abstractionists such as Judy Chicago, James Turrell, and Lee Ufan have already worked on the gradient, but artists who seek to explore this line of research abound today: for example, Loie Hollowell (1983), Maximilian Rödel (1984), Aron Barath (1980), Ruben Benjamin (1994), and Alejandro Javaloyas (1987).

One of the characteristics of this new painting is its individual connotation. Young artists hardly form groups, they do not gather in movements. Wanting to identify the most recent movements in art history we have to go back to the last part of the last century, with the new European painting on the one hand and the Contemporary Realism of the United States on the other (Alex Katz, Eric Fischl, Philip Pearlstein ... ): in Europe, speaking of painting, the last experiences that we can connote as groups were, for example, those of the Young British Artists (Tracey Emin, Ian Davenport, Fiona Rae... ), of the Neue Leipziger Schule (Neo Rauch, Hans Aichinger, Isabelle Dutoit... ), of the new Italian figuration (Daniele Galliano, Marco Cingolani, Andrea Chiesi... ) within which groups such as the Officina Milanese (Giovanni Frangi, Marco Petrus, Luca Pignatelli, Velasco) or the Nuova Scuola Palermitana (Andrea Di Marco, Alessandro Bazan, Francesco De Grandi, Francesco Lauretta, Fulvio Di Piazza) were further born, to arrive at thelast Italian group, the only one born in the 2000s, the Italian Newbrow (Giuseppe Veneziano, Giuliano Sale, Vanni Cuoghi, Silvia Argiolas, Michael Rotondi, Laurina Paperina, Fulvia Mendini and others). Artists, moreover, almost all of whom are still active (we are talking, after all, about artists around fifty to sixty years of age, and for Italian Newbrow even in their thirties) and with outcomes that are often far more interesting and qualitatively superior to those of their younger colleagues, who rarely choose to work in groups or share ideas. Partly because of the transformations mentioned above: digital cosmopolitanism facilitates connections but paradoxically induces working alone (we all experience this, after all: we carry a tool in our pocket that has the potential to connect us to anyone in the world, but we feel much more alone, because we have the perception that digital connections are not as authentic, spontaneous and rich as physical ones). Somewhat because the developments in art in the last fifty years have sent the historiographical models valid up to the twentieth century into the dustbin: with such a vast and varied panorama it seems that it makes less and less sense to identify who first does something, without considering that it becomes increasingly difficult to innovate in a profound way, it becomes increasingly difficult to set oneself up as a breakthrough artist, as an artist (or a movement) that marks a watershed between different eras. And some because of practical considerations: “Artists are now too busy taking inventory for exhibitions, fairs and auctions to think about art movements,” wrote Scott Reyburn in The Art Newspaper. That may sound like a cynical remark, but that is the situation.

The only scene that can resemble a movement (which, however, is far from homogeneous and, in the case, would still include personalities working separate from one another but can be united by so many similarities) sees at its center a type of painting that we might find perhaps more innovative than what has been seen so far (it is so at least from a technical point of view, sometimes less so on the level of content, which indeed at times still seems tied to postmodern ideas), and which works on the borderline between analog and digital: a post-digital painting, we could call it, disturbing an adjective indeed now somewhat dated but nevertheless useful to indicate an art form that was born with the domain of information technology. The outcome is a production resulting from the combination of drawing or design conducted in the digital sphere( graphics processingsoftware, virtual reality programs, and so on) and the application of traditional techniques. Pioneering in this sphere have been the works of German Albert Oehlen, who as early as the 1990s created his “computerized” paintings, or those of Texan Jeff Elrod, who has developed what he calls frictionless painting (“frictionless painting”): his works are thus born in a virtual space and produce a rendering that is then transferred to canvas with a technique that combines digital printing and manual application. Alongside Elrod must be mentioned at least one other U.S. painter, Wade Guyton, author of paintings that run along the frontiers between figurative and abstract and are created from screenshots of Web pages, scans, and prints of Word sheets on which simple shapes or letters are imprinted, after which the same canvas is run through an inkjet printer, with the idea of bringing out clearly, even overbearingly, the conditioning that digital tools exert on our lives. Elrod and Guyton, then, are credited with paving this road, which is being traveled today by several painters in their twenties and thirties. The common intent of these artists is to explore the limits of painting by digital means, often focusing more on technique than content. Thus, New Yorker Avery Singer (1987) creates her paintings with 3D modeling software for engineers, through which she prepares models that she then transposes to canvas with an equally machine-driven airbrush (sometimes her processes change, however). There is no shortage of recognizable elements in Singer’s paintings that often refer back to the imagery of the Web: on the other hand, his peer Jonathan Chapline (1987) is linked to a singular figurativism, who starts instead from environments modeled in virtual reality, then translated onto canvas where landscapes and interiors come to life, merging reality and imagination with an aesthetic strongly linked to American figuration of the last century. Again, the Anglo-American Emma Webster (1989) is the author of a landscape painting with a dreamlike and visionary character that starts from sketches drawn on the screen, in virtual reality, then enriched by a theatrical lighting: the result is landscapes that seem natural, or at least directly inspired by nature, but which are actually the result of a digital processing.One can also include in the count the Californian Petra Cortright (1986), who produces paintings from digital images (which she often fishes variously from the web), with the addition also of real “digital brushstrokes,” which are then printed on canvas through industrial processes.

Finally, to close this rapid and necessarily incomplete overview, a mention of a particular phenomenon that is not new, but has greatly amplified in this first quarter century, and which we might call "neo-mannerism." that vast array of artists who rework the aesthetics of precise moments in art history with forms of revival more or less adherent to the source language, regardless of content, has thus expanded. The panorama is vast. Going quickly, a few examples fished out from among the most quoted, most famous or most talked about young people in recent times: the neo-baroque (Jesse Mockrin), the neo-rococo (Flora Yukhnovich, Michaela Yearwood-Dan, Mia Chaplin), the neo-impressionists (Lucas Arruda), the neo-surrealists (Rae Klein, Sarah Slappey), the neo-fauves (Tunji Adeniyi Jones), the neo-expressionists (Doron Langberg, Jennifer Packer, Antonia Showering, Yukimasa Ida), the neo-cubists (Louis Fratino, Danielle Orchard, Leon Löwentraut), the neo-pop (Szabolcs Bozó), the neo-graffiti artists (Aboudia), as well as generic derivatives that recall easily identifiable models, e.g. (with illustrious precedent in brackets) Anna Weyant (John Currin), George Rouy (Francis Bacon), Roby Dwi Antono (Margaret Keane), Cristina Banban (Jenny Saville), not to mention artists who still seem to be tied to a postmodern painting (Allison Zuckerman, Sarah Cwynar).

Of course, what has been said so far represents a snapshot of a present situation, alive and in flux, and the artists included in the overview are in constant and full activity, which is why the picture could change rapidly (an artist might abandon one strand of research and embrace another, a neo-Mannerist might seek a different and more interesting synthesis, a new movement, perhaps even disruptive, might be born the day after tomorrow, and so on). This is the main reason why it is not easy to try to frame the present, especially when some unseen elements make the work even more difficult: the enormous number of artists at work in the world today (perhaps humanity has never known such a vast number of artists active across the planet) and the consequent difficulty of delving into everything (I do not exclude, therefore, given also the non-exhaustiveness of this quick overview, that I have overlooked or left out some names, if not disruptive, since in the age of global interconnectedness it is difficult for something truly disruptive to escape attention, at the very least important), the great proliferation of events that follow one another from week to week (biennials, fairs, events, exhibitions, discussions), the very structure of the market, with increasingly professionalized artists working for an ever-widening audience of buyers and collectors that requires, therefore, artists constantly at work and constantly producing new works. Hopefully, however, we have at least been helpful in providing some insights.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.