It was Vincenzo I Gonzaga, in 1595, who began the Galleria delle Metamorfosi, destined to become a few years later one of the most astonishing rooms in the Ducal Palace in Mantua, home to the ducal library and a varied and eclectic collection of objects from around the globe. A sort of Wunderkammer, a “chamber of wonders,” that would have housed bizarre, extravagant, curious and rare pieces from the natural world. However, it was not until 1612, under the duchy of Ferdinando Gonzaga (1612-1626), that the architect and painter Antonio Maria Viani, who was entrusted with the project, completed the work with the decoration of the ceiling. And it was under Ferdinand that the Gallery was set up to house the Gonzaga court’s collection of natural objects.

Anyone who had visited the Gallery of Metamorphoses until before April 2022 (except, of course, for the long closure period of almost ten years due to the damage suffered in the 2012 Emilia earthquake) would have found it inexorably empty. Admittedly, the ceilings still retain the stucco decorations and part of the paintings, highly praised in Giovanni Cadioli’s 1763 guidebook (“The purpose for which I have properly led you here, gentle passegger,” wrote the scholar addressing the reader directly, “is that you observe its factory, divided as it is into four rooms with their respective vaults all worked with medals, decorated with stucco, and expertly painted”), but the rooms were completely bare: only the panels on the walls signaled to the visitor the ancient presences that crowded this succession of four rooms. Now, however, from April 2022, the Metamorphosis Gallery will be completely renovated: in these rooms, the director of the Ducal Palace, Stefano L’Occaso, wanted to have a collection of objects arranged that recall the Wunderkammer of the Gonzaga family. It is the project Naturalia e Mirabilia. Science at the Court of the Gonzagas, a permanent exhibition that does not intend to reconstruct in a philological manner the congeries of unusual objects that inhabited these four small rooms, but to suggest the atmosphere, to show the public what the Gonzaga’s guests could find in the Gallery, to raise its curiosity and to convey the fascination that the chamber of wonders inspired in its ancient visitors. An important milestone for the museum, said L’Occaso: the idea is to enrich the Ducal Palace tour “shedding light on an aspect of the eclectic collecting of the Gonzaga family,” with a new section that “will allow even more to work with schools and new audiences, who may not have visited the palace yet and are looking for a more fun and unusual experience.”

Since this is a re-enactment and not a reconstruction, it is explained to visitors from the very first panel that the material deployed in the Gallery is the result of recent purchases, all dating back to 2020, 2021, and 2022. Many are period objects, while others are recent items (this is true, for example, of the shell collection) that, however, by type, could just as well have been appreciated and purchased by those who frequented a seventeenth-century court. And they have been arranged in a modern arrangement, designed by architect Massimo Ferrari of the Milan Polytechnic, which recalls the frescoed quadratures on the walls of the rooms (and thus refers in part to what has survived from antiquity), but which presents itself to the eyes of visitors as an organism that is “deliberately unconventional, light and enjoyable,” declares the Ducal Palace, "also designed to appeal to schools but not without the philological rigor on which the memorable 1979 exhibition entitled Science at Court was based, which was an opportunity to explore scientific approaches between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, revealing the use and function of these and other spaces in the Ducal Palace."

The Gallery takes its name from the decorations on the ceilings, dedicated to subjects from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, a book ideally connected to the Wunderkammer: the transformations of matter, evoked by the objects on display in these rooms, were in turn recalled by the mutations undergone by the protagonists of the ancient poet’s mythological tales. We do not know, however, who was the executor of the paintings of the vaults, as part of Viani’s project: the only artist mentioned is Ippolito Andreasi, who undertakes to paint some “plates” for the room, which therefore have not reached us since the entire furnishings have been lost (or perhaps were never made), and a good part of the canvases set in the ceilings have also not reached us. In the first room of the gallery only the empty frames remain, while in the second a few episodes survive: Coronides and Ischi, the metamorphosis of Actaeon into a stag, Latona turning the shepherds of Lycia into frogs, Callisto and Arcade, the metamorphosis of Cornacchia and that of Syrinx. In the third, the central octagonal frame is empty, while around it we observe the transformation of Atlas into a mountain, Triptolemus and Linchus, Mercury and Aglaurus, the metamorphosis of Biblis, Cadmus and Harmonia, Apollo and Python, Hermaphrodite and Salmace. Finally, in the fourth room, the most intact one, we see in the center the Apotheosis of Hercules surrounded by numerous episodes, including some of Hercules’ exploits (the struggles against Antaeus, Acheloos and Nessus, the slaying of Lica) and mythological stories (Ceres being mocked by Ascalabus, Ulysses blinding Polyphemus, Theseus and Ariadne, the metamorphosis of PErnice, Circe and Pico, Circe transforming Ulysses’ companions, the transformation of the Muses into Birds, Aurora asking Jupiter to honor Memnon, the metamorphosis of Aesculapius into a snake, that of Julius Caesar into a comet, Glaucus and Scylla, Venus and Aeneas, the judgment of Midas, the Rape of Proserpine, Eurythion and Hippodamia, the metamorphosis of Diomedes’ companions into birds).

The Gonzaga’s Wunderkammer was divided into four sections: in the first room were arranged minerals and fossils, in the second room were products of the sea such as corals and shells, in the third room were objects arriving from the Americas, and finally in the last room one could admire oddities from the animal world. This scanning suggested that each room was dedicated to the four elements: earth, water, air and fire, respectively. We have attestations of visitors who already walked through these rooms in the early years. The best known is surely Federico Zuccari, the great painter who stayed here, as a guest of Vincenzo I Gonzaga, between 1604 and 1605: the artist recounts in his Passaggio per l’Italia that the “garden rooms” (so called because they overlook the Giardino dei Semplici) composed a “true gratoso appartamento di mirabile vaghezza,” adorned “di soffitte nobilissime.” As mentioned, at the time these rooms did not yet contain the naturalia and mirabilia of the Gonzaga collection: the first description of the chamber of wonders dates back to 1622, and is contained in the Praefatio del Musaeum Franciscii Calceolarii iunioris Veronensis by Benedetto Ceruti and Andrea Chiocco, a work that described the extraordinary private museum of Veronese naturalist Francesco Calzolari. The Latin text celebrates Ferdinando Gonzaga’s “exaggeratissimum conclavium,” which “glows with a great variety of colors with its excellent images and most pleasing to the eyes of the beholder,” and where “wherever you turn, you come across something in which you can be refreshed inwardly and outwardly.” It is Ceruti and Chiocco’s Praefatio that informs us of the division into four “classes” of the Gonzaga’s chamber of wonders, and describes in detail the objects that populated it.

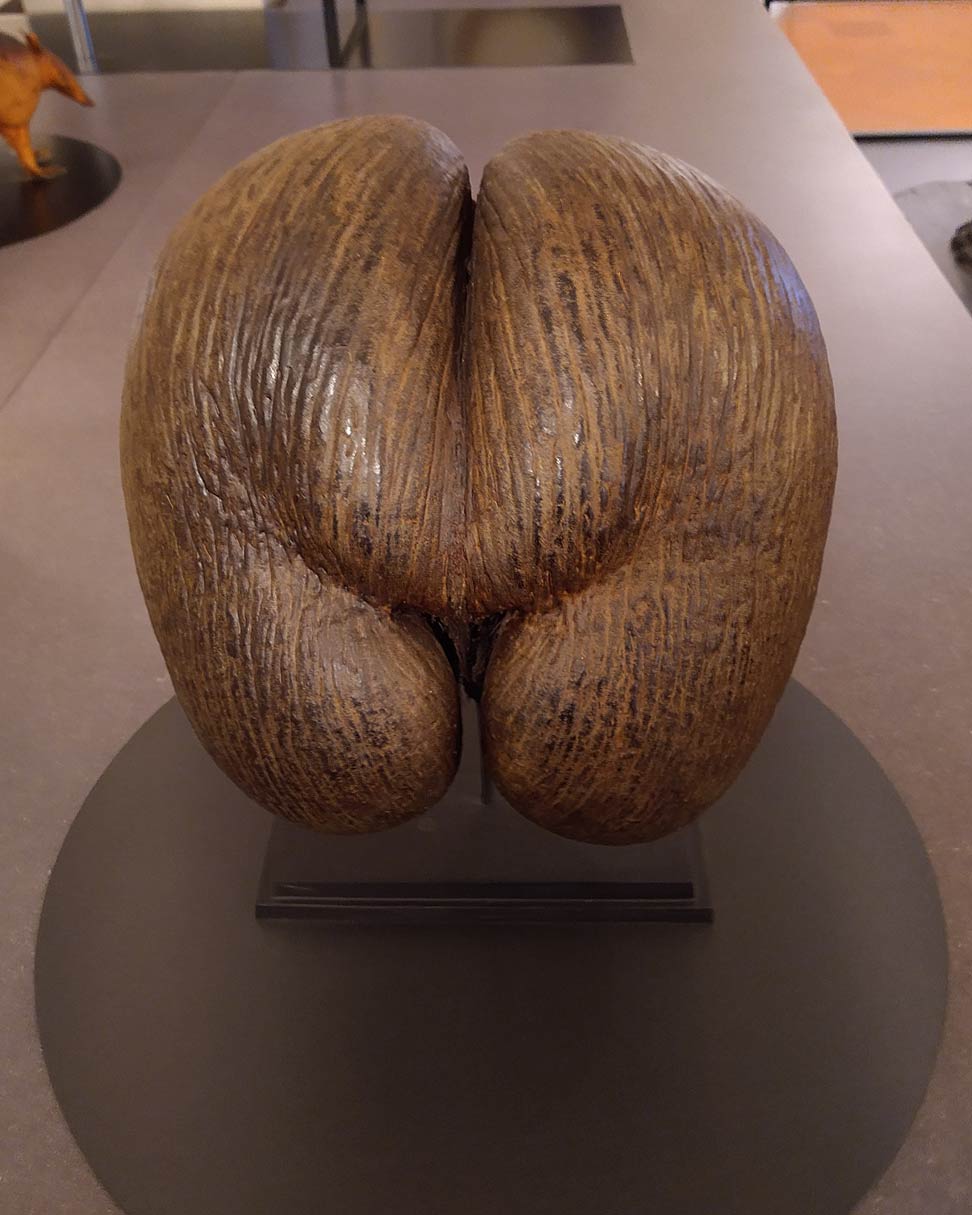

In the first room then here are the minerals (gold, silver, copper, azurite, pyrite, melanterite, sulfur... ), and then the gems, diamonds, rubies, sapphires, amethysts. In the second, reserved for objects of the sea, appeared corals of all shapes and colors (red, white and black), various sea plants, some of them from the American islands, many shells and “innumerable pearls.” As for the class of “fructus Americani,” the objects from the New World, trunks and branches of exotic plants stood out, including what is called in the text “lythoxilla,” that is, “plant-stone,” or some essence that has undergone a process of silicification and thus fossilized. Then, in the same room were arranged four “Maldivae shards,” or the fruits of the coco de mer or “sea coconut,” a plant of the arecaceae typical of the Seychelles, which produces very peculiar nuts that resemble the shape of the female buttocks, so much so that in early botanical classifications this essence was called “Lodoicea callypige.” Finally, among the objects from the animal world, here are “teeth, claws, tails, manes, hairs and the like,” and above all, Ceruti and Chiocco noted, several stuffed animals, including “the only armadillo found in Italy.” Among the rare pieces, the Praefatio, in addition to the armadillo, also names a bezoar, a particular concretion that forms in the digestive system of ruminants to which in ancient times was also attributed a certain curative power, particularly as an antidote against poisons. The gallery also contained some creepy objects, and demonstrated a taste for such oddities by the German traveler Josef Fürttenbach, who visited the Doge’s Palace in 1626 and described with vivid curiosity his passage through the Metamorphosis Gallery in a detailed account: Fürttenbach speaks of “five flayed crocodiles,” “a hydra or dragon with seven heads and as many necks,” and then again “a fetus, or abortion, with a large head and four eyes and two mouths.”

The object that amazed him the most, however, was surely the taxidermied hippopotamus: it is the only surviving original piece from the Metamorphosis Gallery, and today it is kept at the Kosmos Museum of Natural History at the University of Pavia, but it has been on temporary loan to the Ducal Palace. We do not know for sure where the pachyderm came from: it may have been one of the two hippopotamuses that arrived in Mantua, in 1603, banished to Egypt by the physician Federigo Zerenghi, at least according to what Abbot Gian Girolamo Carli reported in the 18th century. What is certain is that it is one of the oldest taxidermies known to us: it somehow escaped the sack of Mantua in 1630 and flowed in the eighteenth century into the collections of the Accademia Nazionale Virgiliana, and then was preserved, at least since 1783, at the University of Pavia. The uniqueness of this hippopotamus lies in the fact that the Gonzagas had placed on it the mummy of Rinaldo dei Bonacolsi, known as “Passerino,” the lord of Mantua ousted in 1328 by Luigi I Gonzaga (the first lord of the dynasty) and killed during the final clash for the seizure of city power. News of the presence of the macabre trophy on the hippo is confirmed by another witness, German writer Martin Zeiler, who saw the mummy in 1630. Because of the gruesome presence, the Metamorphosis Gallery was also called the “Passerine Gallery.” Speaking of the hippopotamus, Fürttenbach wrote of “a sea calf as large as an ox, but not so tall [...]. This beast is put on as if it were alive, it is completely stuffed, the skin is the thickness of an inch. On it stands completely erect the corpse of Passerino Bonacolsi covered with a curtain: he was killed a long time ago by a Mantuan, and one can still see on his skull a very extensive wound; he bled himself so that the whole body superficially, as it is now presented, desiccated just like a mummy. On one side it was opened, so it is possible to see even part of the viscera, which is something to be marveled at not a little.” We do not know what happened to the mummy: legend has it that it was thrown into the waters of the Mincio River by the last duchess of Mantua, Susanna Enrichetta of Lorraine. However, according to a prophecy, the Gonzagas would lose power if they got rid of Passerino’s mummy: thus, in 1707, Susanna Enrichetta’s husband, Ferdinando Carlo Gonzaga, defeated in war and accused of felony, was forced to leave Mantua, was declared a forfeit by the Diet of Regensburg, died in Padua the following year, and the family lost the city for good.

Fortunately, the new exhibit does not offer reenactments of the mummy: however, there are far more interesting elements. The hippopotamus stands out in the first room, although its presence is temporary, and it introduces the second room, where curiosities from the animal world and those from the marine world have been arranged, populating the showcases set up with compartments that recall the wall panels: there one can admire the armadillo mentioned in the Praefatio (this is obviously not the animal present in the seventeenth century: none of the exhibits come from the Gonzaga collection), a coco de mer, the bezoar, a tusk of Gomphotherium (a giant prehistoric elephant that had the peculiarity of having four tusks), a crocodile hanging from the ceiling (upside down according to a custom attested at the time), a pair of skulls of Bison priscus, or steppe bison, found in Rivalta sul Mincio (these huge prehistoric bison, which could be up to two meters tall at the withers, also populated Europe). Among objects from the marine world, here is a sawfish rostrum and, coming soon, also a narwhal tooth (it was thought to be from a unicorn: the one in the ancient Wunderkammer came from the collections of Isabella d’Este), a shark jaw, two cetacean ribs, and a curious guitarfish, a rhynopristiform (the same family as stingrays) that in ancient times was dried and then expertly carved to make it look like a devil, a monster: it was displayed to amaze guests. Interestingly, as the room panels well explain, collecting animal bones was a practice in vogue since antiquity (according to Suetonius, even Emperor Augustus was a collector of this type of artifact), and interest in these objects also encouraged their study: if in the sixteenth century some scientists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Torello Saraina and Girolamo Fracastoro had guessed that fossils had organic origins, it was in the seventeenth century that scientific debate intensified around these objects long thought to be stones that, for some strange reason, took on organic forms (and it was precisely in the seventeenth century, thanks to the study of shark teeth, that the phenomenon of fossilization was understood).

We continue to the third room guided by an ostrich egg, also present in the description of the Gonzaga Wunderkammer according to the Praefatio: it was not an unusual object in the 16th century, since for Christian symbolism it alluded to both the Immaculate Conception and the Resurrection, so ostrich eggs could also be found in churches. Among the most interesting pieces in the third room are the three corals (red, white and black), which therefore faithfully reproduce what Ceruti and Chiocco had seen in 1622, and which had an important religious significance as an allusion to the blood shed by Christ on the cross. Then, in the same room, here are the shells: as seen above, the Gonzaga possessed a large number of them, and they also served as a means of emphasizing the international prestige of the court, since they came from the most disparate places, and were therefore a sign of capillary and widespread relations with other states.

Finally, the last room is devoted to objects from the mineral and plant worlds: the two great protagonists of this section are the amethyst geoid and the fossil trunk, both described in the Praefatio. The geóde is a rock formation covered with crystals, in this case amethyst: it is such a singular object that in 1622 it was even illustrated in a print (there were few objects in the Wunderkammer of the Gonzagas that were given this honor). The fossil trunk, on the other hand, recalls the “lythoxilla” described by Ceruti and Chiocco: in ancient times it was thought that, for some reason, there were plants capable of turning into stones, and this object is particularly illustrative of the qualities that were once attributed to the material, and thus also explain why Ovid’s Metamorphoses was chosen for the decorations.

One last curiosity remains to be satisfied: what was the fate of the Gonzaga’s collection of naturalia and mirabilia? The chamber of wonders lasted very little, and the fate of the objects preserved here, with a few exceptions, followed that of the Celeste Galeria, the family’s fabulous collection of paintings: the art collections were partly alienated in 1627 by Vincenzo II Gonzaga, who sold many objects, at derisory prices, to Charles I of England, and the rest were plundered during the Sack of Mant ua in 1630, when during the War of Succession of Mantua and Monferrato, which sanctioned the handover of the duchy to the Gonzaga-Nevers, the besieged city, upon the entry of imperial troops in July of that year, was brutally sacked and devastated (of the episode, we know from a letter, Pieter Paul Rubens, who had worked for the Gonzaga, also deeply regretted). The army turned on the citizens and did not spare the Ducal Palace: what remained of the Gonzaga collection was stolen or destroyed. It is largely because of this event that few works predating that date have survived in the Gonzaga palace: fortunately, the few remaining paintings among those that decorated the ceiling of the Gallery of the Metamorphoses were saved. And somehow the hippopotamus now preserved in Pavia also managed to escape the devastation, although it is already absent from the palace inventory compiled in 1714, so it is safe to assume that the taxidermied animal had come out a few years earlier.

Today, a true museum of natural sciences has been set up in the halls of the Metamorphosis Gallery, conveying to the visitor the taste for the marvelous that, at the end of the 16th century, dominated in the European courts, and which, with a design that has no equal in Italy, through a modern layout, based on criteria of great scientific rigor and clarity of display, and with a choice of objects faithful to the first description of the Wunderkammer, evokes an extraordinary 17th-century chamber of wonders with an unfortunate fate.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.