As the Vincian year (2019) draws to a close, although further insights appear to be in print, it is appropriate to point out what seems to date to be the most comprehensive summary: Edoardo Villata, Leonard publications of 2019: brief art-historical review, “Art Criticism” 5-6, 2020). In anticipation of forthcoming contributions, I add one more entry of my own to what has been suggestively referred to as “la passion Léonard.” Not to augment a corpus that, for painting, has received some problematic aggregations, but to denounce an improper subtraction; a problem I have cited elsewhere, but which deserves specific consideration.

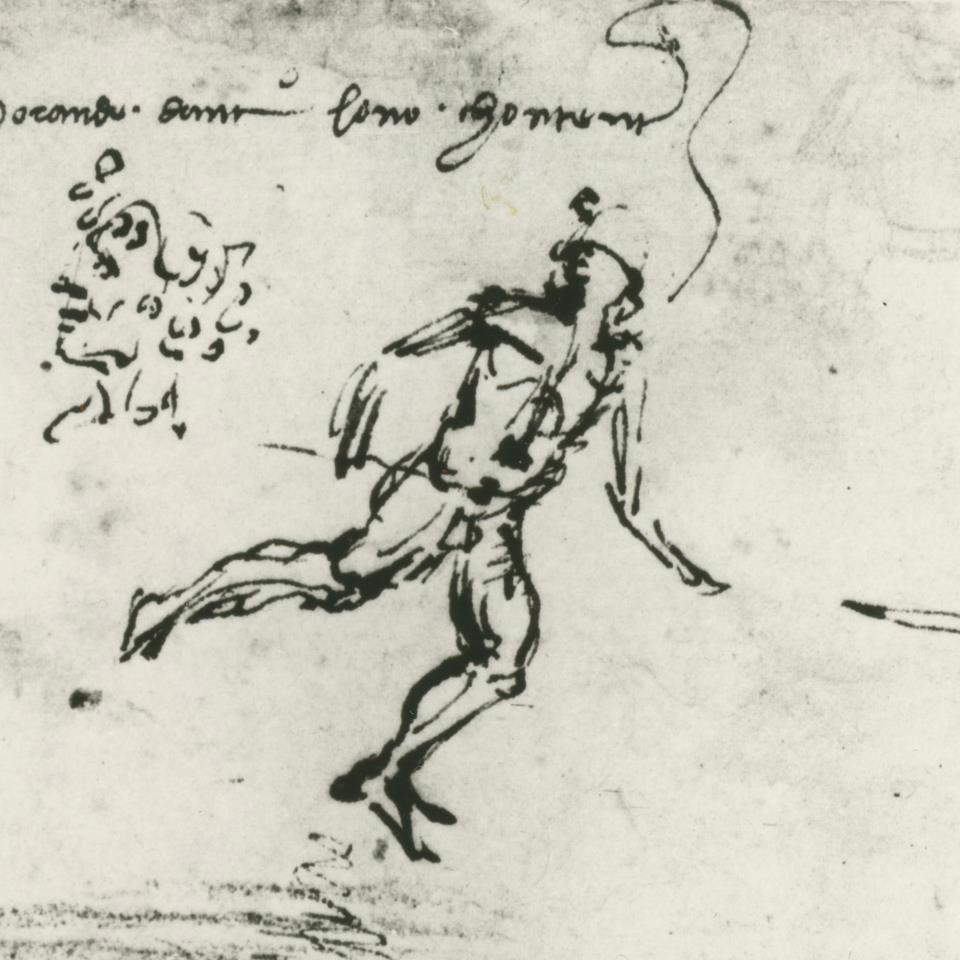

The temptation to intervene on the multifaceted Vincian legacy has always been strong, as an example that is as circumscribed as it is, in my opinion, significant, can demonstrate at the outset. I refer to sheet 8 P in the Uffizi, one of the most famous drawings in the world, recently returned to the limelight and exhibited. For the complex historical-critical affair I refer to an insightful and concurring essay by Alessandro Nova (“ADDJ 5 DAGHOSSTO 1473,” in Leonardo da Vinci on Nature, Venice 2013), and on this occasion I look not at the Landscape on the recto, but at a sketch that appears almost in the center of the verso, a nude athletic figure running, opening his arms, and with his head turned back. Drawing 8 P is a document of rare density, contextualized by the unmistakable Vincian handwriting and the date 1473, yet in the dense relevant bibliography there has sometimes appeared a certain distrust of the sketches drawn on the verso, especially in relation to the dynamically expanded figurine, whose autography has been questioned (fig. 1). Perhaps because of a widespread attitude to create a certain clamor by overturning established opinions: an operation that may be objectively motivated, but which sometimes (and increasingly so in the present day), seems artificially constructed for the sake of visibility.

I observe, in support of what Nova distensively motivated, that a critically flexible method of judgment should be able to distinguish (at a high level, and all the more so in Leonardo’s case) what belongs to distracted scribbling (the young man on the run, precisely) and what belongs to ’study sheets’: indeed, the figuretta finds partial correspondences in the many pen sketches of the early period, which reveal Leonardo’s predisposition to draw and paint ’in order to know’: studies with which the author analyzed, decomposed and recomposed his unmistakable ’posari,’ or attitudes of the human body, whether in a situation of stasis or motion (figs. 1- 2). A summary reference to one of Pietro Cesare Marani’s many papers, “I moti dell’animo,” from Leon Battista Alberti to Leonardo, in Leonardo. The Design of the World, Exhibition Catalogue, Milan 2015, and other relevant essays therein (Bambach, Fiorio, Kemp, Clayton).

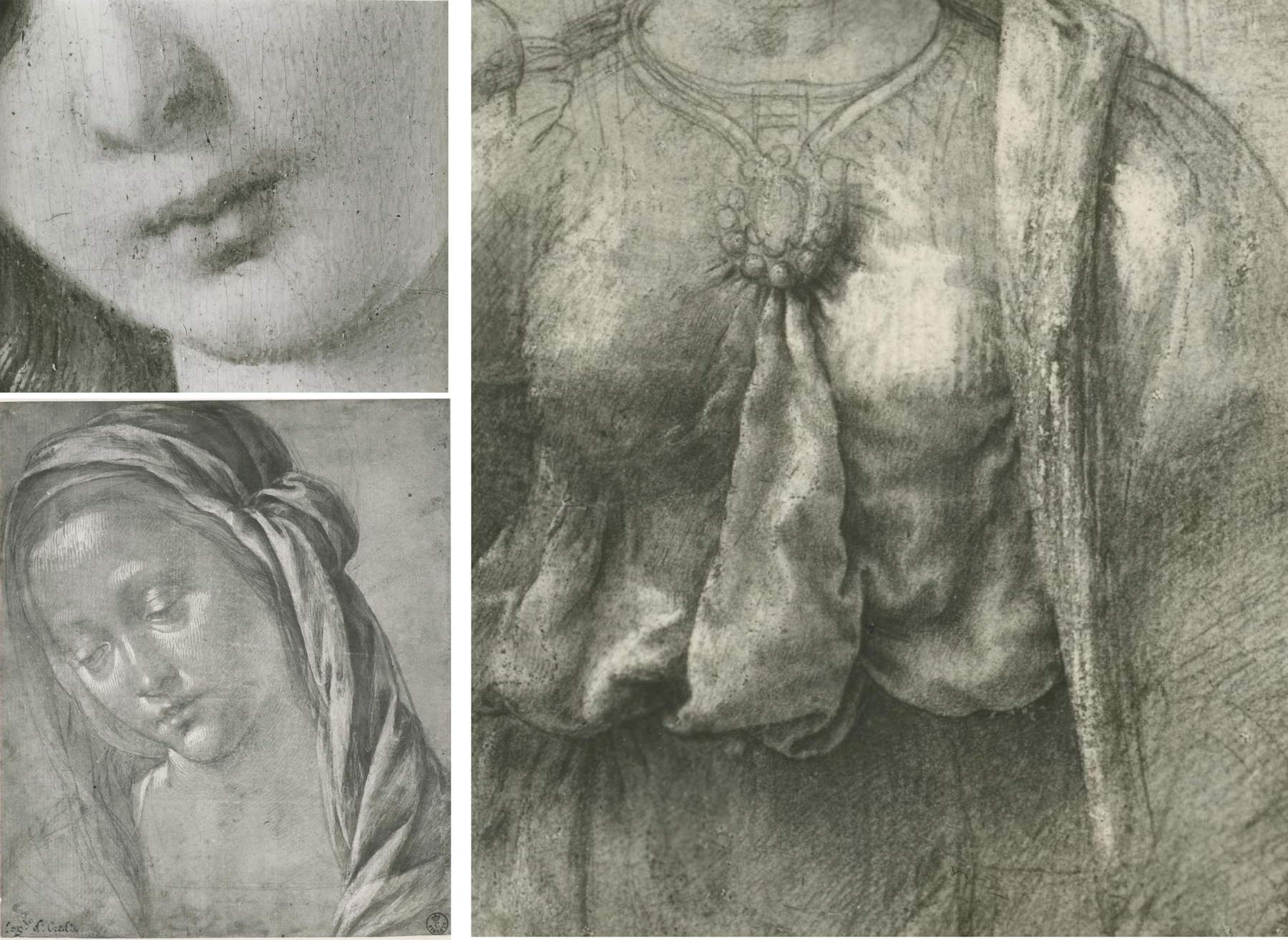

The evidence I would like to bring back to the very small catalog of Leonardo paintings is another, a tiny tablet, namely the Madonna of the Pomegranate preserved in the National Gallery of Art in Washington; a work whose attribution has remained fluctuating for a long time (Verrocchio, Leonardo, Lorenzo di Credi, others) and which today some authoritative voices are returning to bring back to Lorenzo di Credi together with what was probably a preparatory drawing, belonging to the Kupferstichkabinett in Dresden (figs. 3-4). For the material data and the historical vicissitude of the painting and drawing I refer, respectively, to the files of Andrea De Marchi (Catalogue of the exhibition Verrocchio. Leonardo’s Master, Venice 2019), and Lorenza Melli(I Disegni italiani del Quattrocento nel Kupferstichkabinett di Dresda, Florence 2006): I appreciate the work of both scholars, but in relation to the two works I do not share the attributive orientation.

|

|

| 1. Leonardo, Landscape (part.). Florence, Uffizi Gallery, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe, 8P, verso | 2. Leonardo, Figure Studies for the Adoration of the Magi (part.). Paris, Bibliothèque de lEcole Superieure des Beaux Arts. |

|

|

| 3. Leonardo (attr. to Lorenzo di Credi), Madonna of the Pomegranate, also known as Madonna Dreyfus. Washington, National Gallery of Art | 4. Leonardo (attr. to Lorenzo di Credi), Study for the Madonna of the Pomegranate. Dresden, Kupferstich-Kabinett. |

In the second half of the 1560s Leonardo was initiated into artistic activity in the workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio, patronized by a powerful and influential father who had evidently sensed the boy’s abilities. In this sphere, and up to the early 1770s, Leonardo certainly meets other already established young men who occasionally frequented the workshop, but only one name emerges in Vinci’s writings, that of Sandro Botticelli, whom Leonardo mentions in two good-naturedly polemical passages, such as to attest to a high regard on Vinci’s part, and a meaningful frequentation for both. It is, on the other hand, Vasarian Life that juxtaposes with Leonardo the names of other comprimarios and especially that of Lorenzo di Credi, described as a fellow-worker and diligent imitator: “Lorenzo liked the manner of Lionardo out of all proportion...” (Giuntina edition, 1568).

I devoted many of my early studies to Credi, even returning to him several times in recent times; I therefore welcome all those interventions that add something to the personality and work of a painter of good and not mediocre character; but I think it is improper to refer the small Washington Madonna to him. My opinion, hypothetical in detail but credible in principle, is that the “admirable and heavenly Lionardo” (Vasari) working alongside Lorenzo around 1470, granted the younger friend (they were separated by about five years) a definite moment of attention and exchange: basically an amused participation of the vincian in the elaboration of a few drawings and especially of two small-format paintings, a break from the precocious and highly original researches of various orientations: what then appeared to most as the unusual extravagances of a restless young man, and what Vasari, writing in the Lives shortly afterwards, succinctly defined as a “ghiribizzare.” Both the Madonna of the Pomegranate and theAnnunciation in the Louvre (for the sake of brevity I also refer here to the entries in the Catalogue of the 2019 Florentine exhibition) are in fact built on the basis of compositions of traditional cut, well-articulated in space, but lacking the innovative impulses that Leonardo manifested from the very beginning in his pictorial and graphic activity (figs. 5,6,17). In both cases, the execution reveals a process of image growth that, starting from an overall conventional basic scheme, leads to the very delicate and refined ’skin’ of the painting.

A blatantly unheard-of comparison between the Washington panel and the Creedan Madonnas(Leonardo. The Drawing of the World, Exhibition Catalogue edited by Marani-Fiorio, Milan 2015), already revealed a radical difference in the chromatic range, which in the young Lorenzo di Credi’s paintings is based on a limited range of hues intermediate (blue, yellow, green, rarer red) that vary with slight chiaroscuro fluctuations, while the subject matter, laid out with extreme care, emulates the smooth, static sheen of majolica (fig. 9); an open appreciation for Lucca della Robbia’s magisterium that I had once cited, and which I see fittingly reproposed in recent times. None of this in the two tablets mentioned, in the colors that exorbit from the most frequent gradations presenting here and there singular discolorations or brightenings, but which are distinguished above all by a modeling that evokes tactile sensations: dents and bulges preserve traces of a decomposition/recomposition just completed, and betray an imperceptible vitality of the surfaces, which can be felt on close viewing, as the small size demands. Exactly that internal mobility of form that is manifested in the fabric rising in suspension over the body of the maiden depicted in the Dresden drawing, and in the tingling of her hair.

Limiting the discussion here to the Madonna of the Pomegranate, I recall the peculiarity of the types and variations contained not only in Leonardo’s paintings, but also in the drawings. A group of female figures related to the required subject of the Virgin and Child and the Annunciation betray an unconventional choice, usually ignored or misinterpreted by some critical intervention: as shown in the pictures (figs. 10-12, 16-17), some are child mothers taking part in their son’s games with a cat or a flowering twig, barely smiling, and appearing simply dressed, disheveled, with a few locks spilling over their still infantile cheeks, their hair poorly pinned under the piece that characterized married women (fig. 16). It is not impossible that Leonardo looked with a twinge of pity on those young women who often, barely out of puberty, were repeatedly impregnated by husbands of mature age: wealthy men who demanded numerous offspring while procuring recognition of their manhood. Four times Ser Piero, Leonardo’s father and notary of the Signoria, married: two of his four wives bore as many as twelve children, and at least one of them went on to marry at the age of fifteen; I do not think she had many more than the Caterina who begat Leonardo, promptly settled down after childbirth and removed from Ser Piero’s house...

|

| Clockwise: 5. Leonardo, part. of fig.3 6. Leonardo, part. of fig. 4 7. Lorenzo di Credi, Study for a Madonna. Florence, Uffizi Gallery, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe, 1195 E |

|

|

| 8. Leonardo (attr. to Lorenzo di Credi), Madonna of the Pomegranate, also known as Madonna Dreyfus. Washington, National Gallery of Art | 9. Lorenzo di Credi, Adoration of the Child, private collection. |

|

| Row above, from left: 10. Leonardo, Madonna of the Pomegranate (part. of fig. 3) 11.Leonardo, Madonna and Child, also known as Madonna Bénois, part. St. Petersburg, Hermitage 12. Leonardo, part. of fig. 4 Row below, from left: 13.Lorenzo di Credi, part. of fig. 9 (Madonna of Milk) 14. Lorenzo di Credi, Adoration of the Child (part.). London, National Gallery 15. Lorenzo di Credi, Madonna and Child (part.). Turin, Savoy Gallery. |

Of a different sign is the formula of the variously posed Madonna that appears in Lorenzo’s vast pictorial output: in early accounts even the Credian Mary is very young, dressed with care and without refinement, but she responds to an explicit standardization: one and the same faintly expressionless face, the head covered by a veil or cloak, the hair flowing down in regularly wavy bands, the large hands (somewhat clumsy to tell the truth) joining in prayer or closing on the body of the Child according to constantly repeated modules (figs. 13-16, 18-20). Even for the Uffizi Venus, in my opinion a masterpiece with which the painter tried to diverge (perhaps consciously, or at least I hope so) from the triumphant and splendid Botticelli formula of the 1980s and 1990s: the face declares in the first instance coincidence with the Madonnas, the athletic body is stable, a scarf encircles it without fluttering, the hair is composed and only a few strands rise into the air, rigid in curl like a copper foil.

The image preserved in the Washington tablet, though worn down in some features (especially in the Child’s body) reveals a lightness that is concentrated in the outstretched hand, barely flexed at the wrist by the gesture that holds out the pomegranate: in the long fingers exposed in suspension there is a synthesis of explicit novelty, not comparable to the articulations that mark the somewhat prissy gestures of other refined Madonnas of the Verrocchio circle, much less those of Lorenzo di Credi; a hand akin to that which in the great Vincian Annunciation in the Uffizi the Virgin points imperiously at the great codex, manifestly forcing the articulation of the wrist.

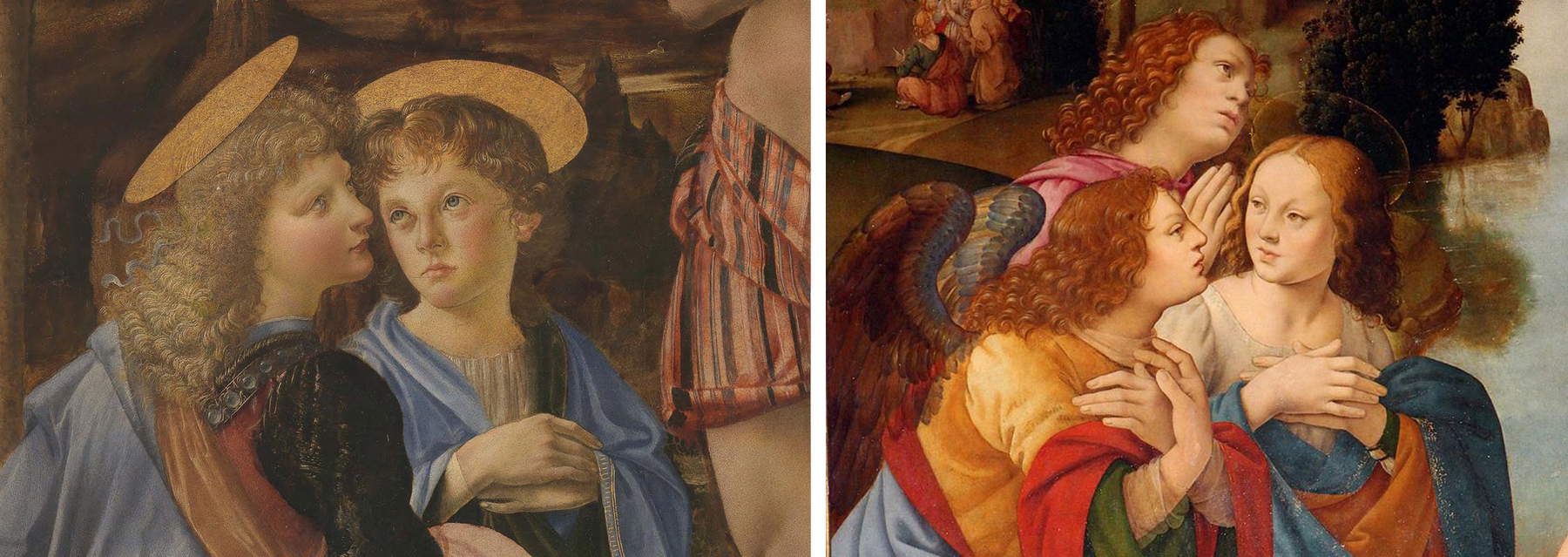

A similar vitality marks the Angel with which Leonardo introduces himself into the unfinished draft of a Baptism of Christ commissioned from Verrocchio and executed in his workshop with the help of a number of collaborators; last, and most invasive, is the contribution of Leonardo, who, starting precisely with the beautiful Angel, will modify what had been begun by taking up the pictorial elaboration of a large part of the panel (fig. 21). It is precisely the Baptism that offers the opportunity to re-propose that Leonardo-Lorenzo comparison that we have already seen in relation to the Madonnas unbalanced in favor of the Vincenzian, not only because of a gap in quality, but because of the unscrupulousness of the one in relation to the conformism of the other. If we juxtapose the Uffizi Baptism with the similar panel commissioned from Lorenzo di Credi by the important Florentine Compagnia di S.Giovanni Battista (now in San Domenico in Fiesole, figs. 21-22), the distinction between the innovative approach of the former and the conventional cut of the latter is explicit, although Lorenzo confirms the consistency of his choices: at the compositional level he takes into account the solution ’reformed’ by the ancient disciple, but the whole is traditional, founded on stable and plastically defined forms; precisely in relation to the Angels witnessing theevent, Lorenzo discards the asymmetry and fluidity of the vincian solution, and perfects his angelic group by reinforcing it in number and reaffirming his fidelity to tradition with a measured selection of colors and an equally calculated distribution of them.

|

|

Row above, from left: 16. Leonardo, Study for a Madonna of the Cat. Florence, Uffizi Gallery, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe, 421 E, recto 17. Leonardo (with Lorenzo di Credi), Annunciation (part.). Paris, Louvre Museum. Row below, from left: 18. Lorenzo di Credi, Head of a young girl (Study for Venus). Vienna, Albertina 19. Lorenzo di Credi, Venus (part.). Florence, Uffizi Gallery 20. Lorenzo di Credi, Head of a young girl. Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland |

|

| Left: 21. Andrea del Verrocchio’s workshop, with extensive intervention by Leonardo, Baptism of Christ (part.). Florence, Uffizi Gallery. Right: 22. Lorenzo di Credi, Baptism of Christ (part.). Fiesole, San Domenico. |

|

|

Clockwise: 23. Leonardo, Madonna of the Carnation (part.). Munich, Alte Pinakothek. 24. Leonardo (attr. to Andrea del Verrocchio), Study for Madonna of the Carnation Paris, Musée du Louvre, Département des Arts Graphiques 25. Leonardo, Study of a female head. Florence, Uffizi Gallery, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe, 428 E |

I return, in conclusion, to Leonardo’s youthful activity and the subject most in demand by his patrons, namely the image of the Madonna and Child. There is a slight trace in the documents that may betray a change in orientation : an autograph note containing the date 1478 sees Leonardo pointing out a moment that must have had some importance for him: the beginning of two paintings (“Incominciai le due Vergini Marie... ”)which unfortunately we cannot identify. These were perhaps two challenging commissions that led him to revise his way of looking at the character of the Virgin and the birth of Christ, and that led him to devise for theAdoration of the Magi, around 1480, a divine group surrounded by a court at once obsequious and fearful. We cannot have certainties, but undoubtedly the Madonna of the Carnation (Munich, Alte Pinakothek, fig. 23), proposes a different typology than the one I have ideally gathered around the sheet with the Madonna of the Cat; enhancing formulas of the Verrocchio style that in the early years of his apprenticeship he had perhaps polemically discarded, Leonardo elaborates an ambitious solution, perhaps in search of a success that was slow to come in Florence, and indeed in his youthful years was denied him. The protagonist of the Munich table is a luxuriously dressed and elegantly coiffed mother, bound to her son by a relationship of dynamic imprint, so much so that the offering of the long-stemmed carnation takes on the tone of a small ceremony. Considered in relation to two Female Head Studies, in which the polished faces are embellished with elaborate hairstyles (figs. 24, 25), the Munich Madonna appears to have been designed for a high-level destination, and is perhaps the one that reached the papal court, succinctly mentioned by Vasari. The craggy peaks that qualify the landscape behind the divine group, and, in the foreground, the artificially clumped drapery and the glass vase with the tuft of flowers, are unmistakable anticipations of what Leonardo would later do by broadening the range of his thoughts and experiments, and which would find echoes, both short and long distance, in the interpretations of his many admirers.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.