Vincenzo Giustiniani, a collector of Macchiaioli.

Art historian Lucio Scardino, in his 1999 survey of art collections in Ferrara in the 20th century, wrote that the most important among Ferrara’s collectors of modern art at the turn of the century was “undoubtedly,” as he took care to point out, Count Vincenzo Giustiniani (Ferrara, 1864 - Forci, 1946), known for his important collection of Macchiaioli painters , which at the end of 2024 was donated to the Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Lucca by Baroness Diamantina Scola Camerini, Giustiniani’s granddaughter, who thus decided, through a generous gesture, to show everyone a significant part of the works her grandfather had collected during his lifetime. The first exhibition of the Giustiniani collection, Art Between Two Centuries. Works from the Vincenzo Giustiniani Collection 1875-1920 , has been organized at the Complesso di San Micheletto in Lucca, under the scientific direction of Paolo Bolpagni, which can be visited from November 16, 2024 to January 6, 2025. It is a first public exhibition before the study and cataloguing of the works donated to the Foundation: works by Giovanni Fattori, probably the artist most present in the collection, stand out, and then Plinio Nomellini, Galileo Chini, Giovanni Boldini, Telemaco Signorini, Eugenio Cecconi, Odoardo Borrani, and Luigi Bechi, mostly in small format, according to a taste widespread at the time when Giustiniani was beginning to compose his collection.

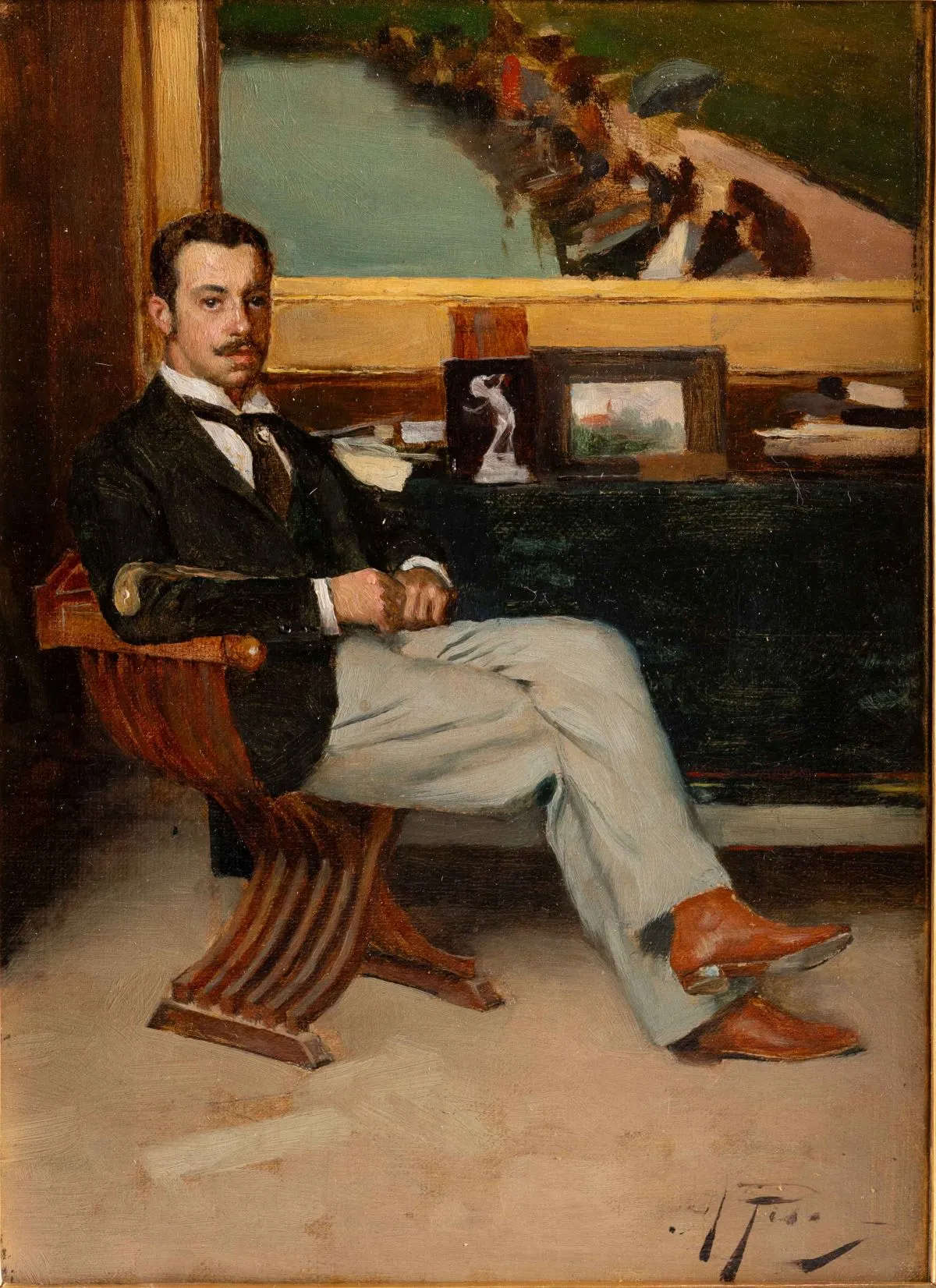

Giustiniani, who was born in Ferrara on July 29, 1864, was a member of the Ferrara branch of the noble Giustiniani family of ancient Genoese origins, which for a long time ruled the Genoese colony of Chios, in the Greek islands, which boasted among its rags literati, as many as eight doges of the Republic of Genoa, and that famous Cardinal Vincenzo Giustiniani, namesake of the ’twentieth-century’ Vincenzo, known for having been a patron of Caravaggio and for having assembled in his palace a fabulous collection with all the greatest masters. Vincenzo at the age of twenty-five married the amateur painter Luisa Nagliati-Braghini, with whom he cultivated a common love of art and particularly painting: the count himself was in fact an amateur painter, and had been practicing drawing and painting since his teens. He had studied together with his contemporary Alberto Pisa (Ferrara, 1864 - Florence, 1930), one of the leading Emilian painters of the early twentieth century: a number of portraits that Pisa made of his friend are preserved, one of which, also of small format, is part of the Diamantina Scola Camerini donation. According to Scardino, it was precisely his acquaintance with Pisa that brought Giustiniani closer to art, rather than the air in his family (Vincenzo’s father, Carlo Giustiniani, who was also elected mayor of Ferrara in 1899, however passionate and connoisseur of the arts he was, did not shine for a particular collecting verve , despite the fact that his collection nevertheless counted important pieces, especially of ancient art: Vincenzo, on the other hand, developed a passion for art that was contemporary to him, although he did not lack expertise in ancient art, so much so that in 1898, together with Giuseppe Agnelli, he was able to write the first guide to the Schifanoia Museum).

Also dating back to the same period were his first artistic experiences in which he was involved as a protagonist: in fact, from 1902 he joined Galileo Chini (Florence, 1873 - 1956) in running the Società Arte della Ceramica, the Chini family company active between 1886 and 1910 and specialized in the production of the famous Art Nouveau ceramics. Later becoming “Arte della Ceramica Fontebuoni,” it availed itself of Vincenzo Giustiniani as a financing partner: the nobleman helped to spread Chini’s ceramics to Emilia as well, of which some valuable pieces (as well as a small painted Tuscan Landscape ) are also preserved in the donation to the Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Lucca, witnesses to Giustiniani’s collecting taste and intelligence. The count helped organize several exhibitions of Chini’s ceramics: in 1901 in Ferrara, at Palazzo Massari, and then in Paris, Venice, Turin, Brussels and several other important European centers. After the company closed in 1910, Giustiniani continued to work as “marketing director,” we would say today: for a couple of years he helped bring French Protector Bloc burglar alarms, designed for museums, to Italy, after which he was responsible in Italy for glass work for the Belgian Verrerie de l’Hermitage (the glass decoration of the Teatro Verdi in Ferrara is also due to this assignment), and finally, in 1917, he moved to Tuscany , buying the large estate of Forci and becoming the de facto manager of what today we would call a large farm specializing in the cultivation of vines andolive trees (to this day the Forci estate, which has been passed from the Giustiniani heirs to the Van Ogtrop family, is one of the leading farms in the Lucchesia region, and to the production of the fruits of the earth it also supports a foundation that deals with contemporary art, thus ensuring that the spirit of Vincenzo Giustiniani continues to hover over the hills of Lucca). Upon arriving in Tuscany, Giustiniani devoted himself almost full-time to his art collection, and lived in Forci until his passing in 1946.

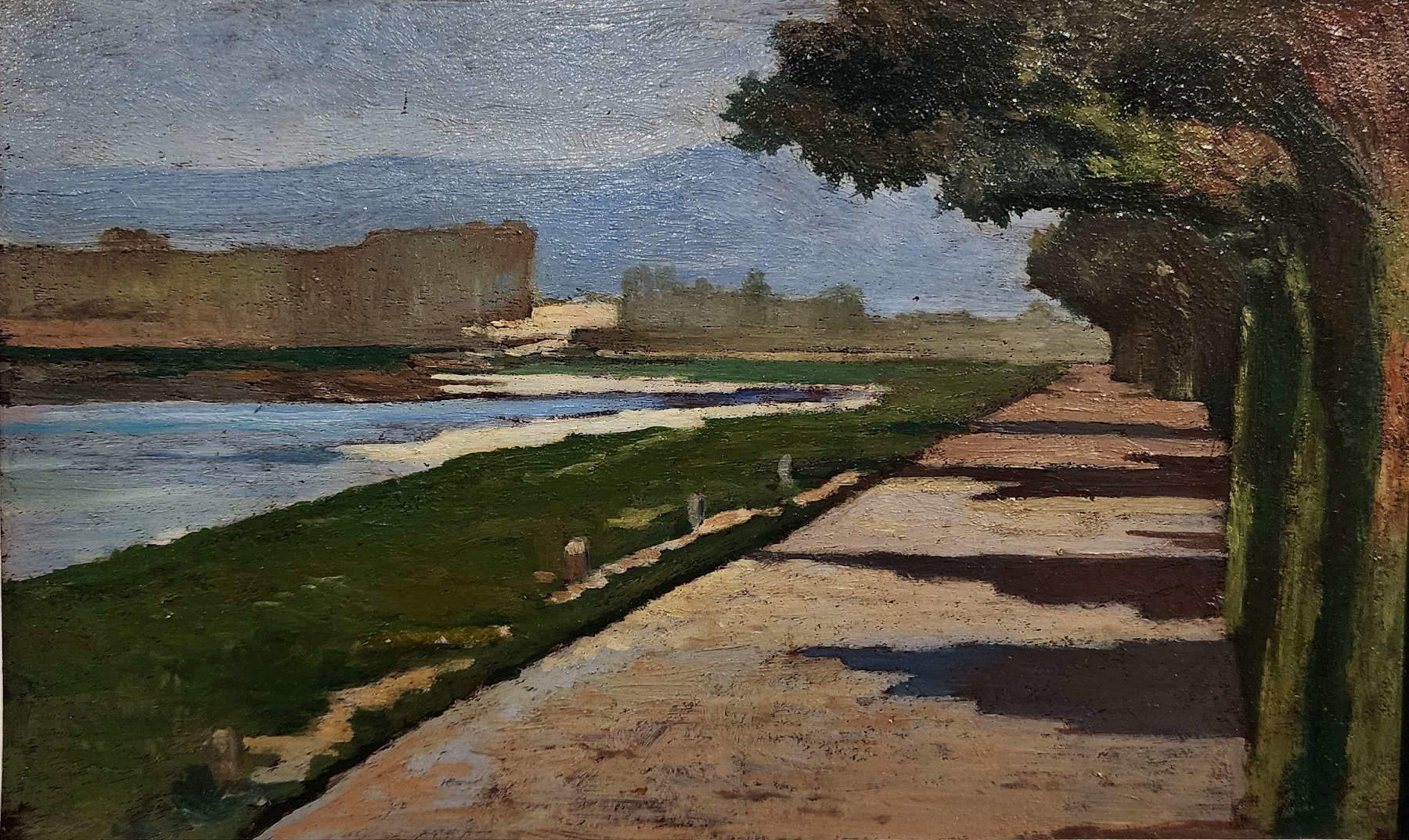

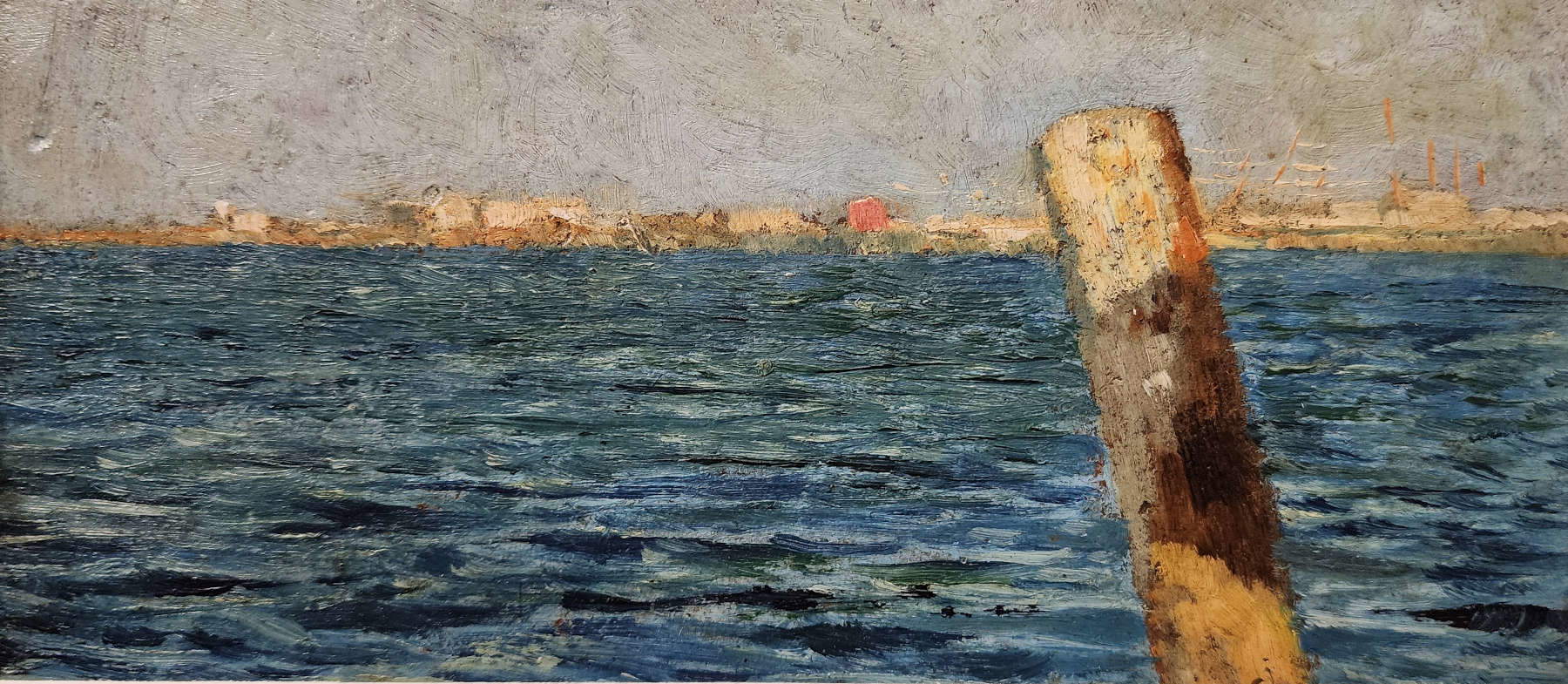

When work left him time, Vincenzo Giustiniani was, we might say, almost totally absorbed in art. He wrote articles on art in the Gazzetta Ferrarese, founded the association, which still exists today, Ferrariae Decus , which is concerned with the protection of the city’s heritage, knew scholars and art historians (he had relations with Adolfo Venturi), was among the jurors at the Venice Biennale of 1907 and 1921, and even curated a major retrospective of Giovanni Fattori as part of the First Roman Biennale in 1921. And of course he frequented dealers, artists, and auctions to replenish his collection. Fattori, as mentioned, is one of the artists most represented in Giustiniani’s collection. Among the most significant works that have come to the Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Lucca are Fishing Boats at Anchor, which is also one of the largest paintings among those remaining in the collection: a large horizontal format canvas that captures a typical early 20th century day in the waters in front of Livorno, with fishermen intent on their daily work, in a scene that succeeds in capturing the soul of the Tuscan coast by orchestrating a color scale of grays, blues and blues that expertly render the tones of the sky and the sea reflecting it on a day of variable weather. The themes frequented by Fattori are all well represented in the small formats of the Giustiniani collection: there are the paintings of military subjects (such as The Shooting in the Field - Maneuvers of Bersaglieri and the Wounded Cavalryman, both small but relevant examples of the Macchiaioli technique), there are the landscapes such as the Piccola marina and the evocative Pineta dopo la bufera, and then again theArno alle cascine and the essential Tronchi di birulle.

Giustiniani developed a predilection for the Macchiaioli especially as he always had the opportunity to frequent Tuscany: purchases were mostly made in the artists’ workshops, or at auctions, or even through merchants, such as Mario Bertini or Aldo Gonnelli. Sometimes it happened that he bought works simply by seeing them on display: Diamantina Scola Camerini, with whom we spoke shortly after the donation was announced, recalled how once her grandfather, after seeing an exhibition by Plinio Nomellini, an artist for whom he had a deep admiration, decided to buy it en bloc. It was the exhibition that Nomellini set up in Florence, in 1919, at Studio Fanfani: 83 works purchased for the sum of 75 thousand liras, which roughly corresponds to 130 thousand euros today. An important sum, but Giustiniani did not spare any expense: “I remember that all the money,” Diamantina Scola Camerini tells us, “went to buy paintings, and in the house there was the maximum of economy, of narrowness almost, but there were always resources available to buy a new painting. And if this on the one hand for the family was quite a heavy burden to bear, the recognition was having a man full of interests, a man rich in culture, a man who knew so many artists because, by buying paintings he also took an interest in the artists’ affairs.”

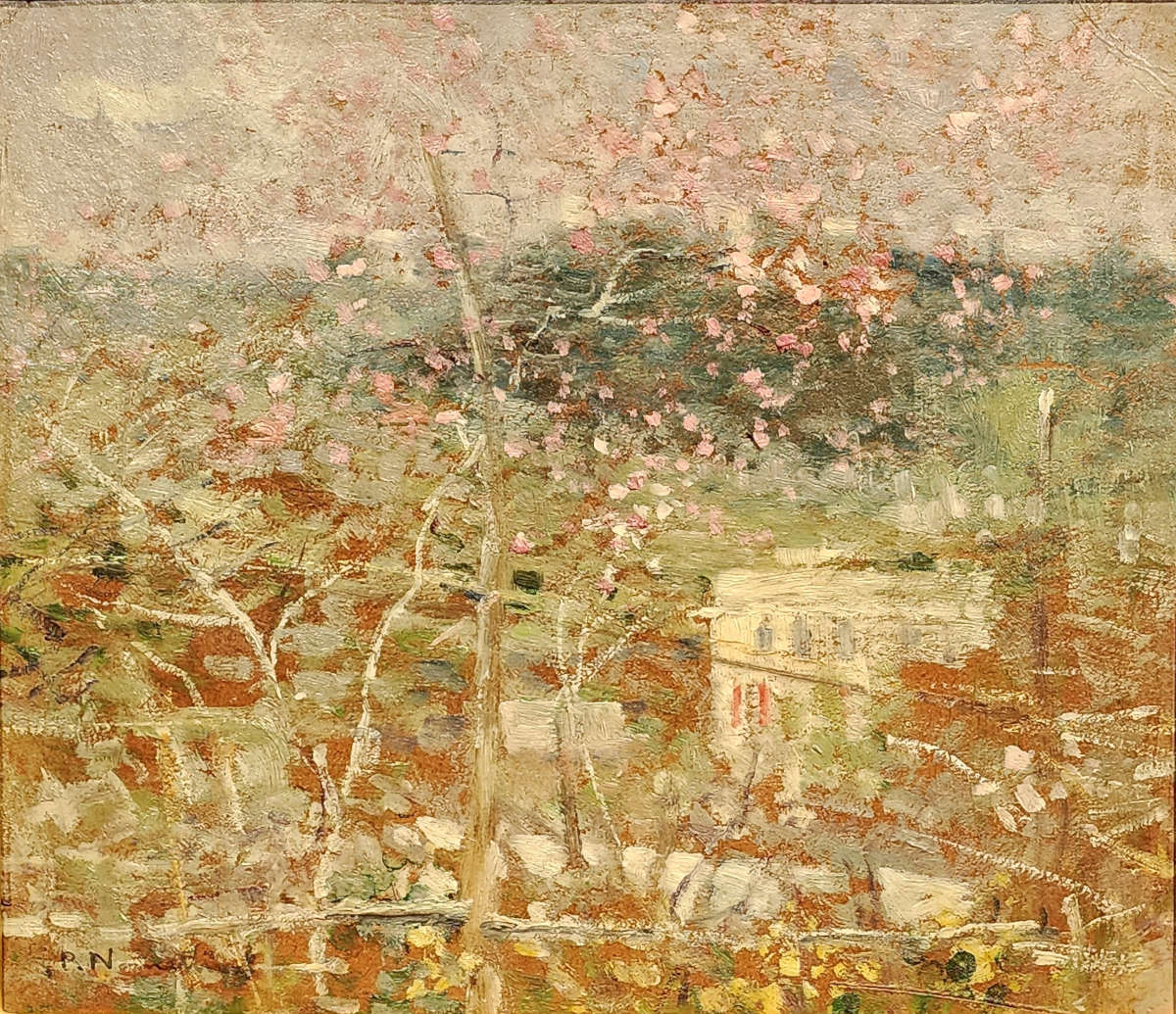

In the donation there remain paintings by Nomellini that the artist executed mainly during the early phase of his career and that denote his early adherence to macchia painting (Nomellini was a pupil of Fattori): the Mare azzurro (Blue Sea ) of 1889, the Paese con pratino verde (Country with Green Meadow ) of 1889, undated but presumed to have been made in the same years, or the Bove che pascola (Ox grazing), all tablets of strict Fattorian observance, are to be read in this sense, although there is no lack of paintings that already foreshadow the later developments in Nomellini’s art, such as the Reaping, a work in which the ears of wheat, rendered with thin, stringy brushstrokes, already hint at Nomellini’s move toward what was to become Divisionist painting, of which he was one of the leading exponents. On the other hand, the Alberi in fiore (Trees in Bloom), a panel in which the blooms are rendered with rapid touches of the brush, are already Divisionist.

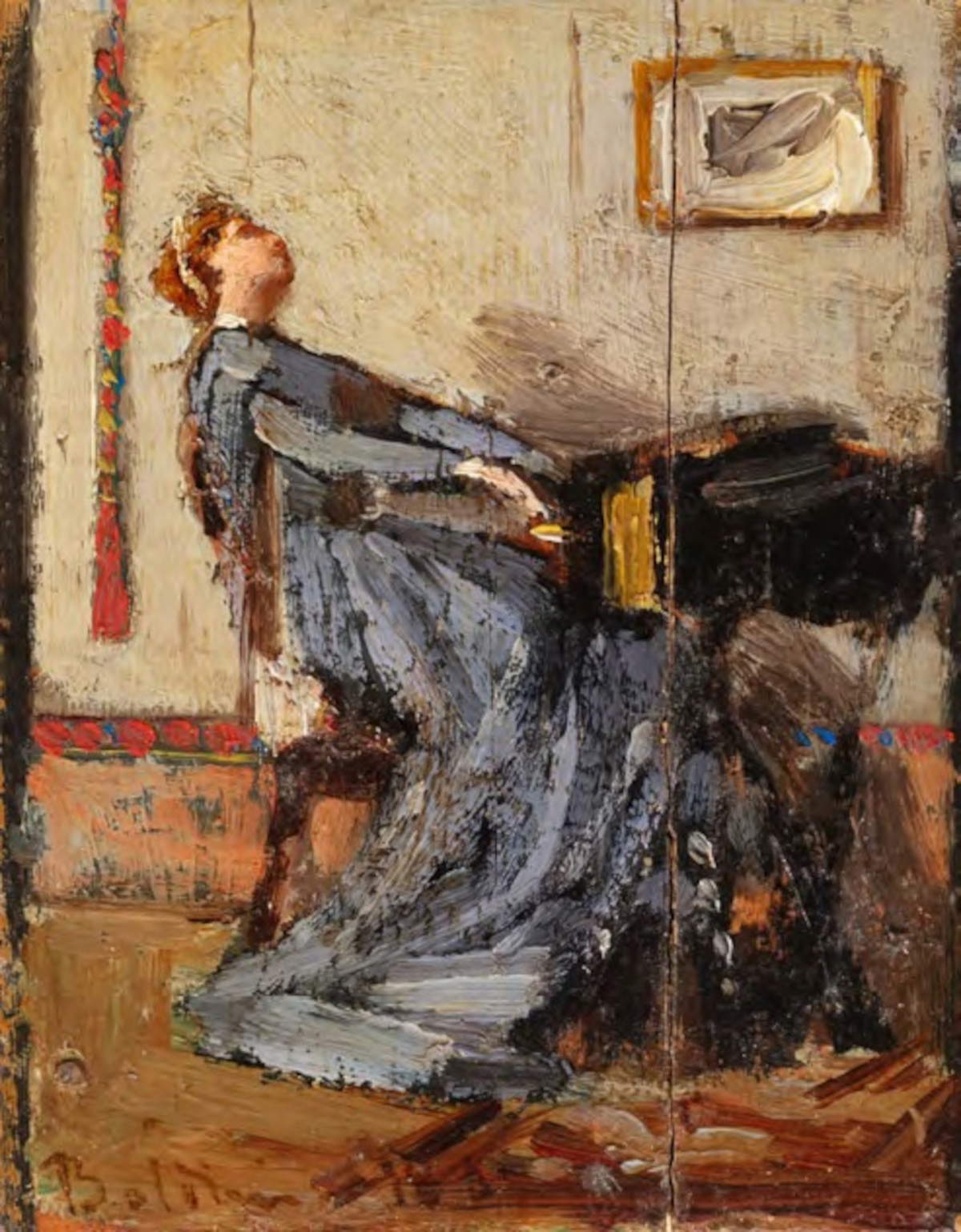

Another artist of whom a couple of small gems are preserved is Silvestro Lega, who is present in the collection nucleus that has come to the Foundation with the Porticciola rossa and especially with the Canto di uno stornello , which is the sketch for one of the Romagnolo artist’s most famous works, now kept at the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Palazzo Pitti in Florence. Then there is one of Giuseppe Abbati’s masterpieces, theArno at the Casaccia, a painting whose sketches also survive: with Abbati we go back to the origins of macchia painting, with a painting that is surprising for the reflections of the village houses on the river waters. By Eugenio Cecconi is a fine Bosco al tramonto, while there are also works by Telemaco Signorini (the Barca sull’arno, the Porticina or the Spiaggia di Leith in Scozia) and Giovanni Boldini, who is present with a portrait of Leopolda Banti alla Spinetta in which the wife of Cristiano Banti, another Macchiaiolo painter (as well as supporter of the group’s artists) is depicted while intent on playing the ancient chamber keyboard instrument. Boldini, from Ferrara like Giustiniani, is another of the artists most represented in the collection.

As for subjects, the count favored landscapes. “The countryside, in particular,” Diamantina Scola Camerini points out. “My grandfather was very fond of nature, of animals,” her granddaughter tells us, also recalling how Vincenzo Giustiniani, when she was a child, had tried to stimulate her passion for art, drawing with her with pencils and colors and teaching her some first rudiments. The countryside was also the subject Giustiniani himself loved to depict in his paintings: the Peasant Girl Stirring Grapes in the Vat is one of the most significant paintings among those executed by the count that arrived at the Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Lucca with the donation.

At its height, Vincenzo Giustiniani’s collection was expected to contain hundreds of pieces. Then, in 1929, with the international crisis that also affected the count’s activities, the collector was forced to sell part of the pieces in his collection, in an epoch-making auction sale (two hundred pieces in all) at the Scopinich Gallery in Milan that was held over three days (December 12, 13 and 14, 1929): some works that were Giustiniani’s are now in Italian museums, for example, Telemaco Signorini’s Bigherinaie at the Galleria Civica Giannoni in Novara, or Giovanni Fattori’s Il carro rosso , which is at the Musei San Domenico in Forlì. Part of the collection has been preserved, however, and in any case Giustiniani never stopped buying works and enriching his collection.

Diamantina Scola Camerini shared with her grandfather Vincenzo Giustiniani a love for Lucca: despite the fact that the family had roots in Ferrara, both she and her grandfather deeply loved this corner of Tuscany. At the time of the recent sale of the Forci estate, the works collected by Vincenzo Giustiniani still decorated, as pieces of furniture, the large Renaissance villa at the center of the estate itself: hence the decision to prevent the dispersion of the works with the act of donation, so that today everyone can see the product of a strong passion for the art of the Macchiaioli, so that that collection remains united by continuing to bear witness to the taste and foresight of those who put it together. “Having no heirs,” Diamantina Scola Camerini concludes, “I thought that the best way to keep the collection and the works of art alive was this: to have it preserved so that everyone can benefit and enjoy it. This is what art should be for: to do good.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.