Vico Magistretti's Atollo lamp: the difficulty of simplicity

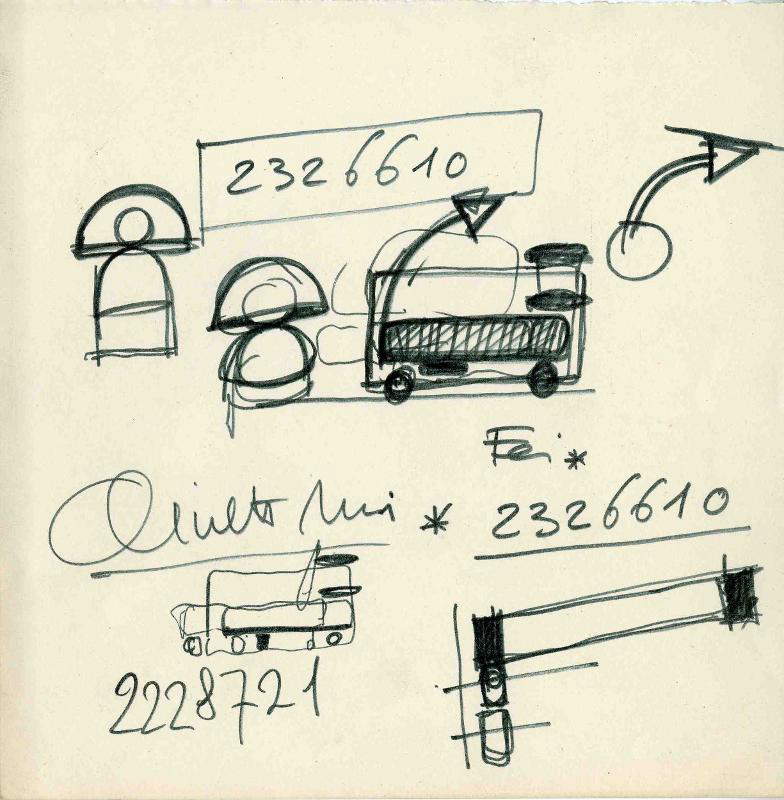

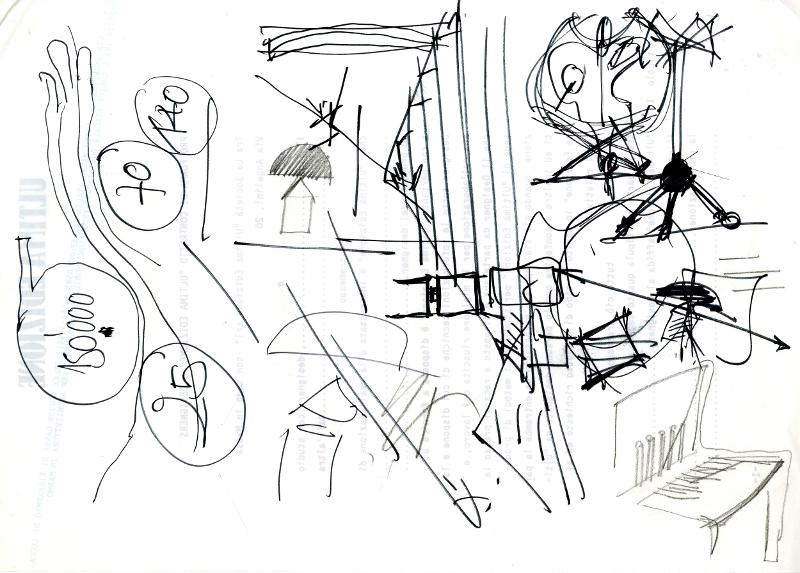

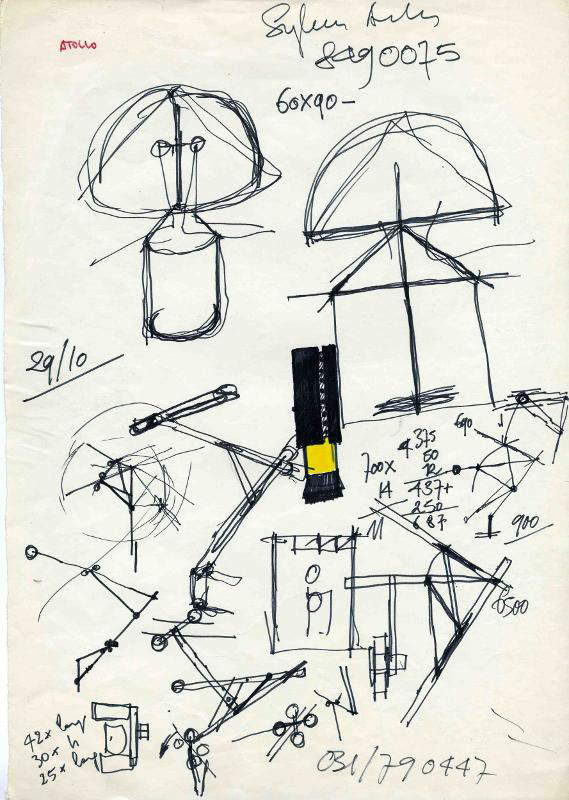

“I was tired of seeing light always used in transparency. I wanted to use light with reflections...” From this intuition Vico Magistretti (Milan, 1920 - 2006) created one of the projects that still stands today as a symbol of that all-Italian design of which he himself was a protagonist. An idea marked by solid simplicity, one of those projects that could be “said over the phone,” that is, told in words, or “by concepts,” without even needing to be drawn: the Atollo lamp. The idea that guides Magistretti is that of a lamp composed of simple, essential, almost archetypal shapes: the cylinder, the cone, the hemisphere. Thus, in 1977, a lamp was born that would soon revolutionize the concept of the table lamp, thanks to its ability to “combine formal solutions and luminous effects.”

Once again the object comes to life thanks to the close relationship between the designer and the manufacturer, a distinctive feature of Magistretti, who sees collaboration and communication between the two parties as the key to good design. The company that will and still does produce Atollo is Oluce, founded in Milan in 1945 and still active in the field of lighting today. Since its founding, the company’s mission has always been to combine aesthetic and technological research, triggering a happy union with the world of design. This happens thanks to the collaboration of personalities such as Tito Agnoli, Joe Colombo, Marco Zanuso and, since the 1970s, also and above all Vico Magistretti, who will remain art director and main designer for years, giving the company some of its most iconic products, including Atollo itself.

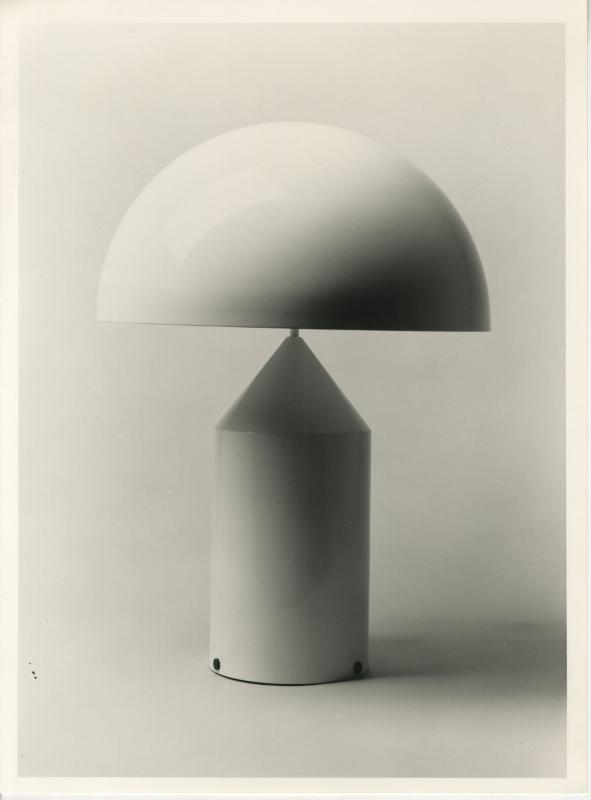

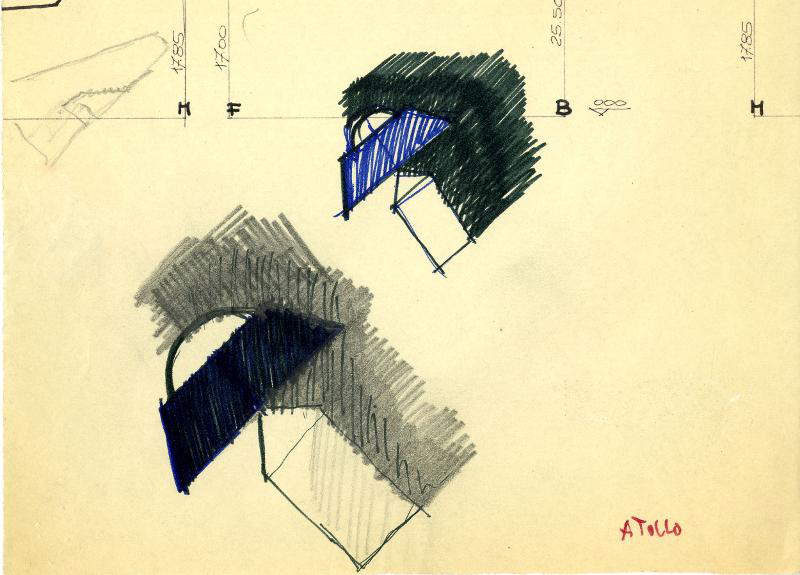

TheAtollo 233, the first model that will be replicated in other dimensional variants and changing the system that regulates the lighting and light intensity, is 70 cm high and composed of a cylindrical base with a diameter of 20 cm, which ends in a cone shape, and supports a half-sphere shaped cap with a diameter of 50 cm. All technical elements remain hidden within the base and the dome, which is lowered (to conceal the light source) and connected to it via a slender, almost invisible support, so as to highlight the geometric rigor of the composition.

The particularity lies not only in theessentiality of the forms, but also in the relationship between the material and the diffusion of light. In fact, Atollo is made of painted aluminum (of which there are several variants, such as white, black, gold, and satin bronze): it causes the outer shell of the hemisphere to remain in shadow and the light inside it to diffuse first on the conical element and in parallel on the cylindrical one. In this way the dome results as if suspended and the lamp is configured as a “luminous sculpture, from which nothing can be taken away, nothing can be added.”

The research does not stop with the use of metal alone, but continues with the creation of variants in both murano glass, transparent or opaline, and in opaline perspex, a solution less loved by the designer, since it recalls that “transparent light” from which he deliberately wanted to distance himself. The desire to create such an object, which was not only essential, that is, reduced to its essence, but gave back a new way of perceiving light, through a careful play of reflections, meant that Atollo 233 won, in 1979, the Compasso d’Oro, and entered the permanent collections of several museums, such as the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, but also, in 2007, in the Permanent Collection of Design at the Milan Triennale.

It is possible to recognize in the Atollo lamp one of Magistretti’s guiding principles, namely, the belief that the object should be useful in itself, and stripped of any decorativism. Magistretti reiterates several times that decoration makes sense only if it arises with the object, and not if it is affixed on top of it, showing that he knows that famous principle so dear to Ludwig Mies van der Rohe: “less is more.” Similarly, he shows that he has learned and reinterpreted the lesson of the Scandinavian designers, known thanks to events such as the Triennale, with “their emphatic-free way of dealing with the everyday, the piece of furniture, the object of use.” In this sense, simplicity becomes a pivotal and indispensable element, no matter how complex it actually is: “It is very difficult to make simple things. Simple things are always the result of extreme complexity. Think of the evolution of a ballet dancer: everything must appear easy, instead... The effort sustained is enormous, but it should not even be seen.” And Atollo in fact hides this effort, behind a facade of essentiality and purity of form, which makes it a current object, not subject to changing tastes, because it stands within the space showing its true nature, valid in all times.

It seems almost unbelievable that Atollo, which has now entered the everyday life of so many people, hides within itself such complexity and at the same time clarity of thought and, above all, constitutes a whole new way of looking at a common object. In this approach to design Magistretti really seems to make his own an old London adage, which, as he recalls in one of his many interviews, was told to him by the Earl of Snowdon: “look at usual things with unusual eyes.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.