Viboldone Abbey, monastic peace amid the chaos of Milan's suburbs

On the one hand, the high-rise buildings of San Giuliano Milanese, the results of the ’building expansionism of the 1960s, the straight line of the railroad, the sequence of banks, grill shops, driving schools, turkish kebabs, hairdressers, furniture stores, insurance companies, convenience stores on the last kilometers of the Via Emilia, once a consular road that facilitated the traffic and movement of the legions along the Cispadana, today a slow and free alternative route that begins at a traffic circle near the Rimini Fair and dies under the signs for Metanopoli and the terminus of the yellow line. On the other side, the industrial area of Sesto Ulteriano-Civesio, Milan’s extreme southern suburbs, the jam of warehouses under the IKEA-Obi-Famila-Burger King-Fashion City-Mondo Convenienza-Pianeta Casa totems, the queues that clog the A1 springs on Friday afternoons. In between, a sliver of countryside. Viboldone Abbey stands here, constrained, pressed, enclosed between the state highway on one side and the highway on the other, guarding what had once been its appurtenances, its lands, its fields. A severe and secluded survivor, together with the neighboring sisters of Chiaravalle, Mirasole, Morimondo, of that system of monastic settlements that arose shortly after the year 1000 to garrison the Milanese plain, a fundamental system for controlling the territory, improving agricultural yields, bringing technological innovations, making the woods on the edge of the city fruitful.

It doesn’t even seem to be a few minutes’ drive from the San Giuliano Milanese toll booth, from the traffic, from the warehouses where families suffocate on Saturdays and Sundays, from the bases of logistics companies, from the swarms of trucks entering and leaving this citadel of consumption, this fortress of commerce, this tangle of tar and concrete. It is enough to avoid leaning out of the agricultural village so as not to break the enchantment: past the last brick building of Viboldone one can already glimpse, beyond the countryside, on the horizon, the outline of the suburbs. One has to stop to have the illusion of not being inside a shred of the past that, for some reason, has not been gobbled up by urban development. Maybe enveloped by its coils yes, but the suburb today must not be all that different from what it must have looked like more than a hundred years ago, when these cottages were still inhabited by field workers. The town may have swallowed the peasants, but not their laterizî dwellings, nor the abbey, which has endured for more than eight centuries.

It had been founded in 1176 by the Humiliati, who a few decades later would also settle in Mirasole. The Lombard landscape at the time was dotted with abbeys. Indeed, the abbeys shaped the Lombard landscape, made it fertile, reclaimed what around the year 1000 was an area of inhospitable swamps, set up crops, opened canals, and helped make the Bassa one of the most luxuriant agricultural areas in all of Europe. Viboldone is the abbey that has perhaps best maintained its appearance, and its integrity, said Sandrina Bandera, longtime superintendent of Milan, “is not just its architecture: it is its perfect relationship with the surrounding nature, and Viboldone Abbey is perhaps the most complete testimony to this unified vision between culture and nature, between intellect and the harmony of color, light, and water.”

The Humiliati remained here until the year 1571, when Pope Pius V suppressed the order: Carlo Borromeo would have liked to reform it, but the humiliati were firmly opposed, to the point that one of them even went so far as to fire an arquebus at Borromeo, who managed to escape the attack and probably thought that the only way to bring the humiliati back to mild counsel was to use strong-arm methods. The friar who had shot him ended up on the gallows, and not even six months later that order of ancient origins that preached work and sobriety, that had faced accusations of heresy, that had been the first in history to recognize even laymen as its members, also died. Then came the more framed Olivetans, who did not fail to pay homage to the one who had been their de facto benefactor, since we see Charles Borromeo, already a saint, depicted dispensing miracles on a canvas placed to decorate one of the 17th-century altars of the abbey church. The Olivetans remained here until Milan came under Austria, then the Austrians also began their suppressions, and Viboldone Abbey, this time, was abandoned. Only in 1940 did the monks’ cells come back to life: Cardinal Ildefonso Schuster offered the abbey to a community of Benedictine women, who have not left since. And they continue to live here, in the silence of the abbey, while not even five hundred meters from their retreat flows the roaring traffic of the metropolis.

The nuns’ day begins when most of the city is still asleep. Morning office shortly after five o’clock. At seven o’clock praise. At eight o’clock the Eucharist. At noon the prayer of the sixth. At six in the afternoon, vespers. Daily, with slight time changes on Sundays and holidays. Ancient rhythms while all around chaos rises, prayers and work amid the clanking of Frecciarossa trains, amid the loudspeakers of shopping malls, amid the bustle of commuters in columns between the interstate and the highway, between downtown and the suburbs, between the suburbs and downtown, on the interchanges and side streets, toward the ring road, toward the first circle of avenues, toward no one knows where and no one knows what. Instead, there is peace here in Viboldone, in front of its tripartite red-brick facade designed and planned to rise toward the sky, in the courtyards in front of the monastery, between the aisles of the abbey church dedicated to Saints Peter and Paul. It happens often to see the nuns in the church, the only portion of the monastery to which visitors have free access. And it is also the reason why people usually visit the Viboldone complex: here, however, there is not the orderly siege that is laid on Chiaravalle Abbey every weekend, nor is there that air of conviviality that one breathes at Mirasole. At Viboldone there is calm, most of the time one is alone, hearing nothing but the sound of one’s own heels on the terracotta floor.

At the church one enters through a wooden doorway that is still that of the time of the construction of the simple gabled facade, a very rare case. Before entering one stops to look at the mullioned windows open to the sky that lighten and soar the three sectors into which the two half-columns divide the façade; one lingers on the white marble portal, on the lunette of the architrave where a Madonna and Child between Saints Ambrose and John of Meda find their place, works whose author has not yet found a name, and is still called “Master of the sculptures of Viboldone.” A still unknown artist who must, however, have had certain Lombard origins, a vigorous, sturdy, firm sculptor, but one who knew how to be caught up in moments of intense delicacy, as one who has good eyesight and can catch the motion of gentleness in the hand of the Virgin caressing the Child, or one who has a very good zoom on his phone and can capture the sincere expression of that solemn, peasant Madonna looking down on those entering the church.

Inside the church are the same bricks as on the facade, used for the squat columns dividing the three naves of the basilica layout and supporting the cross vaults. When the church was built, the bricks of the columns and the arches were colored red, even though they were already red: the intention was to avoid any kind of chromatic dissimilarity that might occur in the natural coloring of the brickwork. One immediately notices the frescoes that decorate the interior: they were made over a span of at least thirty years, but it would not seem so. The decoration has been able to maintain a harmony, a balance, it knows how to give an impression of unity. To think that, until 1938, anyone entering here would have seen nothing: the Olivetans bleached out all the decorations, a coat of white to erase the entire legacy of the humiliated. Then, three and a half centuries later, a first restoration had the merit of resurfacing the ancient paintings.

One is greeted by a cascade of colorful little flowers that stand out against the white walls, mixed with stars composed of eight red palmettes alternating with as many dark buds and from which depart eight wavy black rays: it is a decoration also found in other Lombard buildings of the time (the basilica of San Bassiano in Lodi Vecchio, for example), and it is the friars’ way of telling us that we have arrived in heaven; it is the “celestial tapestry,” as Hans Peter Autenrieth called it, signaling our entry into the kingdom of heaven. A similar function is probably served by the segmented irises that decorate the center of the vaults and restore a suave sense of lightness to the observer. Giuseppina Suardi, the restorer who worked on the Viboldone frescoes between 2014 and 2015, noted the extraordinary unity of painting and architecture: a decoration of flowers and stars, which might appear trivial to us, here becomes functional to give aesthetic unity to the rooms, following a circular course to accompany the architecture. Not only, then, a symbolic function, which is nonetheless essential to lead the visitor to the chapels with the painted scenes.

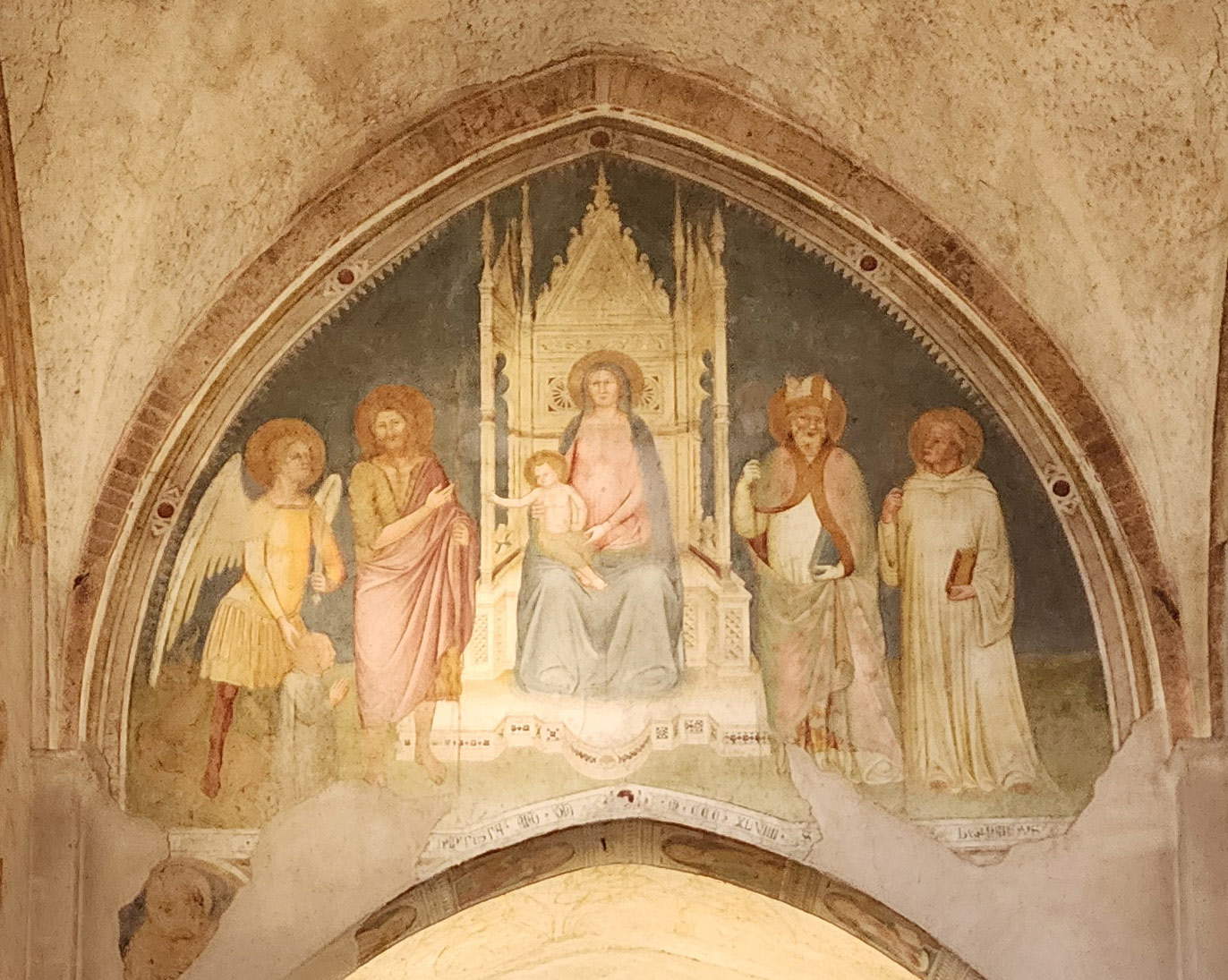

The provost who commissioned the frescoes, Guglielmo da Villa, called to Viboldone artists from Tuscany, or at any rate those who looked to Tuscany, who attended to the decorations throughout a thirty-year period: one notices, in the background, a votive fresco, namely, a Madonna and Child Enthroned surrounded by Saints Michael, John the Baptist, Ambrose and Bernard and honored by a donor, which is dated 1349 and was probably the first scene to be completed, or at least dates from the first phase of the decorations. We do not know whose hand painted it: we cautiously refer the work to an undefined “Master of 1349.” Having dropped some past proposals, such as that of identifying him with a follower of Maso di Banco or other assorted Tuscans, it cannot be ruled out that he was a local, young painter, open to the innovations that Giotto had also introduced in Lombardy, staying in Milan between 1335 and 1336. Longhi, on the other hand, thought the exact opposite, namely that this artist was a Tuscan called to Lombardy and fascinated by certain chromatic softnesses, certain brightnesses typical of Milanese painting: the fact remains that the firm, plastic figure of the Virgin seated on that magnificent Gothic throne that looks like ivory is as close to Giotto as can be admired here at Viboldone.

Few doubts, however, about the scene facing the votive fresco, the masterpiece of the entire fresco cycle, namely the Last Judgment , which critics have almost unanimously assigned to Giusto de’ Menabuoi, here engaged in painting one of the most visionary of medieval art, with Christ the Judge who, from his mandorla with the colors of the theological virtues, accompanied by a host of angels, divides the blessed from the damned while the dead open wide the lids of their tombs. The blessed are facing him, they are kneeling, as in the case of the friar in whom the effigy of the patron has been sought to be recognized, or they are praying to him with folded hands, a dense and orderly array opposed instead to the chaotic throng of the damned, some already in the mouths of a ravenous Lucifer who is rendered as a sort of horned bear from whose body snakes set out to bite sinners who are not beaten by the devils, including one who curiously wears a tiara, almost a denunciation of the corruption of the Church. Above is the curious, tasty detail of angels rolling up the sky sanctioning the end of time and the beginning of eternity, which begins behind the gem- and gem-quilted walls of the heavenly Jerusalem. One recognizes the typical elements of Giusto de’ Menabuoi’s painting before the Padua Baptistery undertaking: the firm forms, the lightness of color, the hieraticity of Christ and the angels, the expressiveness of the figures. One can read here one of the best pages of 14th-century Italian art.

Less easy to read, however, is the rest of the decoration, which is developed in the vault of the triumphal arch, on which we see painted a Crucifixion by a still different hand, a hand that reflects the spread of Giottism in northern Italy, but which remains difficult to decipher, like the one that painted the stories of Christ on the vault (the Annunciation, the Adoration of the Magi, the Presentation in the Temple and the Baptism) and on the side walls: on the right here are scenes from the Passion (from above the Last Supper, the Kiss of Judas and the Oration in the Garden side by side, and then below thegoing to Calvary and the flagellation), while on the left, as an ideal continuation of the Crucifixion, all that happens afterwards (the Deposition, further below the Ascension and the Incredulity of St. Thomas, and in the lower register the Pentecost). All realized within panels, as if we were witnessing a story in pictures, the illustration of an illuminated codex. A tale still in search of its author, a tale that is still waiting to give a name to the hand that painted those slender and elegant figures, those colors so soft and unreal, those scenes that “open like bellows” on the vaults, Longhi observed, scenes that evade the law of gravity to follow instead the trend of triangular scores, something that a Tuscan would hardly have done, while more likely the work of one of those Lombards accustomed to “isolate and abstract now one or another of the figurative modes [...] and push it to the greatest and most complex expressive capacity.”

It is inside places like these, under frescoes like these, that one gets to know a Church that is far from the official one. Paolo Rumiz, in Il filo infinito, his journey among the Benedictine monasteries undertaken to retrace their history, to try to understand today’s Europe through the Europe of that time, wrote that here at Viboldone one feels “better than elsewhere that the Church is not structure, it is not the cardinals, the power, and perhaps not even the pope. The Church is these frescoes, it is this landscape. It is the solitary prayer of a lost creature faced with the unspeakable, a prayer that becomes song, first solitary and then choral.” Of course, perhaps even beneath these frescoes it is difficult to forget what the Church is beyond these walls. But that we have the perception of being “aboard a lifeboat,” of having arrived in a port after having sailed in the middle of a sea where the sacred has become superfluous, this is so. We notice it. We live it. And perhaps it is so for everyone, even those who do not believe in the God of Christians. The rising city is back here, ready to grip you, it is pressing, looming, perhaps even threatening, it is near. But it could not be further away.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.