Urbino Renaissance--from theory to practice: the Annunciation by Giovanni Santi

One of the main protagonists of the Urbino Renaissance, namely Giovanni Santi (Colbordolo, 1440 - Urbino, 1494), is best known today for having been the father of one of the greatest painters the history of art can remember, Raphael Sanzio (Urbino, 1483 - Rome, 1520): in reality, remembering him exclusively for his illustrious son does not do justice to his high artistic stature. Certainly, on Giovanni Santi has weighed for centuries the heavy judgment of Giorgio Vasari, who had described him, in the first edition of the Lives, as a “not very excellent painter, indeed not even mediocre,” an assessment later limned in the Giuntina edition: “not a very excellent painter, but so good a man of good wit and apt to direct his children by that good path which to him, by his ill fortune, had not been shown in his youth.” A prejudice that, apart from a few pioneering nineteenth-century contributions (beginning with that, dating back to 1822, by Luigi Pungileoni, the first to separate Giovanni’s activity from that of his unwieldy son, and continuing with those of Crowe and Cavalcaselle, and the research of international scholars such as Johann David Passavant and Henry Austen Layard) it was demolished only in the twentieth century, first with a few essays in the 1930s (above all the one of 1934 by Raimond van Marle), and then in the second half of the century thanks to the studies of art historians such as Renée Dubos, Ranieri Varese (author of the first Italian monograph devoted to the artist: it was published in 1994), Pietro Zampetti and Rodolfo Battistini, who helped to redraw the physiognomy of this long-forgotten artist, and finally definitively delegitimized him with the important monographic exhibition that the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche in Urbino has organized, from November 30, 2018 to March 17, 2019, to mark another important stage in the path of his revaluation.

Rodolfo Battistini has described Giovanni Santi as “not a great artist but one of wide culture”: and indeed he was not only a talented painter, but also a scholar (in 1482 he wrote a long poem, La vita e le gesta di Federico di Montefeltro duca di Urbino, a terza rima composition of over twenty-two thousand verses: to provide a yardstick for comparison, the Divine Comedy numbers just over fourteen thousand), playwright (for the theater, one recalls his Amore al tribunale della pudicizia of 1474, a play he not only wrote but also directed) and, wishing to use a modern yardstick of judgment, also an art historian, since in his aforementioned rhymed chronicle on the life and deeds of the Duke of Urbino there is no shortage of judgments on artists that show how vast his knowledge of art was. On Mantegna, for example, he wrote that “et certamente la natura, Andrea / dotò de tante excelse e degne parte, / che già non so se più dar potea. / Perché de tucti i membri de tale arte / lo integro e chiaro corpo lui possede / più che huom de Italia e de le externe parte.” Santi was also among the earliest admirers of Leonardo da Vinci, an artist whom he compared to Perugino (when he wrote the poem about Federico da Montefeltro, Leonardo was just twenty-five years old) in a list of painters active in Florence: “due giovin par d’etade e par d’amori / Leonardo da Vinci e ’l Perusino / Pier della Pieve che son divin pittori.” Flattering opinions also those on van Eyck and van der Weyden: “A Brugia fu, among the others most praised / el gran Jannès, e ’l discepul Rugiero, / cum tanti di excellentia chiar dotati / ne la cui arte et alto magistero / di colorir, son stati così excellenti / che han superato molti volte el vero.”

And indeed, the theme of comparing the real to the painted was very passionate about Giovanni Santi, who of the Italian painters of the late fifteenth century was among the most attentive to the descriptive languages of the Flemish painters. There is a particularly interesting passage in his rhymed chronicle, and one on which scholars have long focused their attention, which reads, “Who is that which may the clear color / lucid and transparent of a ruby / ever counteract its vague splendor? / Who is that which may the sun in the morning / ever paint / or a mirror of the waters / cum fronde e fior vicini al loro confino ? / Which ever so excellent in the world was born / that a white lily makes or fresh rose / cum quel bel pur ch’a natura piacque ? / El paragon se trova ove ogni cosa / Vinta riman né si può causare / al paragon sufficiente chiosa”: in these verses, Giovanni Santi wonders if there are really painters who are able to capture the “lucid and transparent color of a ruby” by reproducing its splendor, if there is someone capable of perfectly restoring a lily or a rose, and, ultimately, if art can really imitate what is found in nature. Many critics have read this passage as Santi’s negative criticism of painters who strive to create paintings that are as close to the real thing as possible: a different interpretation, however, is that of art historian Kim Butler, who, on the contrary, catches a vein of irony in the words of the Urbino artist, and argues that one would not explain certain attempts on Santi’s part (above all, those in making many gems and precious stones that adorn his characters and which, Butler points out, were always “rendered with great accuracy”) if one were to take the verses of his chronicle literally. One of the interesting aspects of Giovanni Santi’s production is that, thanks to the bulk of his writing, it is possible to try to identify, in his artistic practice, the echoes of his ideas, and particularly illustrative in this regard is one of his greatest masterpieces, theAnnunciation now in the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche in Urbino.

|

| Giovanni Santi, Annunciation (c. 1489-1491; oil on panel, 260 x 187.2 cm; Urbino, Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, on loan from Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan) |

|

| Giovanni Santi’sAnnunciation on display at the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche in Urbino. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Giovanni Santi, Annunciation, detail |

|

| Giovanni Santi, Annunciation, detail |

|

| Giovanni Santi, Annunciation, detail |

|

| Giovanni Santi, Annunciation, detail |

Giovanni Santi executed the painting around 1489, commissioned by Giovanna Feltria della Rovere (Urbino, 1463 - Rome, 1513), the last member of the Montefeltro dynasty and mother of Francesco Maria della Rovere (Senigallia, 1490 - Pesaro, 1538), the future duke of Urbino. The work was probably commissioned precisely to celebrate the arrival of the unborn child, the second male child of Giovanna (who in turn was the daughter of Federico di Montefeltro) and her husband Giovanni della Rovere, duke of Sora, and was intended for the church of Santa Maria Maddalena in Senigallia, a city to which, moreover, the work temporarily returned in 2014: in fact, during the period of the Napoleonic spoliations, and in 1809 to be exact, it was sent to the Pinacoteca di Brera, where in all likelihood it was exhibited together with other paintings from the Marche, and to which, moreover, the work still formally belongs, although it has been granted since the 1960s for exhibition in Urbino. For the sake of completeness, it should be added that, in 2009, the Pinacoteca had tried to re-obtain the work from Urbino (along with the predella of the Montone Altarpiece, a work by Berto di Giovanni from Perugia), and unanimously critical voices had been raised from the Marche region, however. After a few days, the Milanese Superintendency had given up on re-obtaining the work, but in return had asked and obtained that theAnnunciation be moved from Raphael’s house, where it was then located, to the National Gallery, where it is still displayed today.

The scene takes place, as per Renaissance iconography, under a beautiful portico overlooking an enclosed garden (thehortus conclusus symbolizing Mary’s virtues): the Virgin stands under the portico and the angel is just outside, having just arrived (his wings are still spread), while he, also as per iconography, bears the lily symbol of purity to the Virgin, who is about to kneel with her hands clasped on her chest as a sign of respect. Above, the Eternal Father observes the encounter from a large roundel and, beside him, the infant Jesus made flesh descends on a pink cloud holding a cross. Finally, behind the figures a vast hilly landscape opens up, the kind that was probably familiar to the artist from the Marche region.

On this Annunciation, critics have expressed somewhat oscillating opinions. Adolfo Venturi, who in his Storia dell’arte italiana thus described the painting, placed himself in negative terms: “Again lenorme God the Father, within a multicolored ring; again larchitettura with marble coverings, imitated by that of Fra Carnovale; the country with the side rock and globose mountains, as in Paimezzano. LArcangelo takes on an aspect of grace, and the somnolent Madonna is clothed in humility.” Rather harsh were also van Marle, who called theAnnunciation“mediocre,” and Crowe and Cavalcaselle, who spoke of it thus, “the figure of the Virgin has the usual gentle characters and forms which, more or less, are noticed in all Our Women of the Saints. That of the Eternal Father is likewise of a somewhat vulgar type and form as Our painter used to do in such figures. LAngelo has a very loose move not devoid of grace but a little studied, and svelte forms with good proportions.” Passavant, who in his 1882 work Raffaello d’Urbino e il padre suo, Giovanni Santi had described the drawing as “harsh” and the coloring as lacking in harmony, was also very rigid. Far too enthusiastic, however, were the remarks of Fréd Berence, who wrote in 1936 in his study Raphaël, ou la puissance de l’esprit: “s’il avait peint, ou plutôt s’il nous était resté, quatre ou cinq tableaux de cette qualité, il aurait sa place entre Mantegna et le Pérugin. Il se dégage de l’ensemble de l’uvre une sincérité immédiate, à laquelle Pérugin n’a jamais atteint, une sévérité qui rappelle Mantegna, avec moins de précision, et Piero della Francesca, avec moins de puissance” (“If he had painted, or rather if we had four or five works of this quality left, [Giovanni Santi] would have found his place between Mantegna and Perugino. The composition gives off an immediate sincerity to which Perugino never arrived, a severity that recalls Mantegna, with less precision, and Piero della Francesca, with less power.”). Drawing the conclusions would be Ranieri Varese in his 1994 monograph: “the almost unanimous negative judgment seems to us unfair and not corresponding to the real quality of the painting which demonstrates a conscious and sure use of the elements of perspective construction and, while attentive to the experiences of contemporary painters, does not renounce autonomous choices.”

TheAnnunciation is, in fact, an interesting compendium of the interests, theories, cues and, indeed, autonomous elements that make up the art of Giovanni Santi, an artist who remained faithful to his own ideas for almost the entire span of his career, and produced works in a style that, over the years, hardly changed (consider also that Giovanni Santi’s first dated work is the Gradara altarpiece of 1484, and that the artist passed away in 1494). The aforementioned Kim Butler has carried out a close analysis of Giovanni Santi’s iconographic sources, and all that is evident from the “practice” of the painting finds a timely match in what we may consider a kind of “theoretical statement” formulated by the painter in his poem The Life and Deeds of Federico di Montefeltro Duke of Urbino. Butler begins with the Eternal Father, whose facial morphology would recall those of Melozzo da For lì (Forlì, 1438 - 1494): the frescoes of the Sanctuary of the Holy House of Loreto, contemporary or slightly earlier than Giovanni Santi’sAnnunciation (who cited the Forlì artist as the “Melozzo a me sì caro / che in prospectiva ha steso tanto il passo”) come to mind, in particular. Continuing on, the Virgin is an almost slavish quotation of the Madonna found in the cymatium of the Polyptych of St. Anthony by Piero della Francesca (Borgo Sansepolcro, 1412 - 1492), the sumptuous work now in the National Gallery of Umbria in Perugia but originally executed for the convent of Sant’Antonio in the Umbrian capital: for Butler, this is evidence of Giovanni Santi’s presence in the city. But from Piero would also derive the idea of placing the characters appearing in the sky on a diagonal line leading toward the Virgin: in Piero it was the dove of the Holy Spirit, in Giovanni Santi, however, it is the Eternal Father in the round (the one that to many commentators has seemed almost bolder and intrusive) and the Child Jesus made flesh. A choice that, for Butler, “proves fruitful both for the perspective depth and for the geometric order of the composition, which proposes an almost rational interplay of rectangular, semicircular, circular and triangular forms”: Giovanni Santi, in short, makes his own Piero’s propensity to set compositions on solid geometric patterns.

There are also important suggestions from the art of Leonardo da Vinci, the young man whom, as we have seen, Giovanni Santi greatly admired. We can find them in the figure of thearchangel Gabriel, and for Butler there are even three “points of contact” that the Marche painter’sAnnunciation reveals with the counterpart Annunciation that Leonardo painted between about 1472 and 1475 and which is now in the Uffizi. The artist from Vinci introduced the iconographic novelty of the archangel kneeling directly on the grass in the garden-an idea that is punctually taken up by Giovanni Santi. The second tangency with Leonardo lies in the pose of the figure, which almost traces a drapery study by the Tuscan genius, now preserved in Rome at the Istituto Centrale per la Grafica: some scholars have speculated it was a study for theAnnunciation. Santi, too, gathers the drapery around the angel’s feet (as well as the Virgin’s): “these techniques,” Butler points out, “together with meticulous foreshortening of the figures, manage to give the protagonists dynamism, in sharp contrast to the static figures, with linear, columnar draperies, of Piero della Francesca’s painting.” And finally, a further demonstration of interest in Leonardo’s work, is the study of shadows, which exudes a certain attention to research on optical effects by the young Vinci artist. Then look at the jewel adorned with pearls that stops on the chest the surcoat of the archangel Gabriel: an interesting example of Giovanni Santi’s glyptics, the large brooch, with the light that makes the pearls and gold parts shine, contradicts to some extent the intention outlined in the chronicle of letting go of challenges to nature, since the painter is clearly in search of those same effects of verisimilitude that he also tries to achieve with the softly shaded shadows of the two protagonists.

|

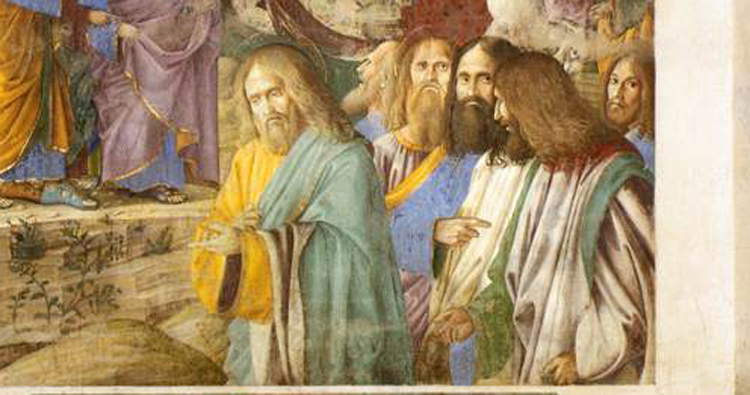

| Melozzo da Forlì, detail of the faces in theEntrance of Christ into Jerusalem, fresco at the Shrine of the Holy House of Loreto |

|

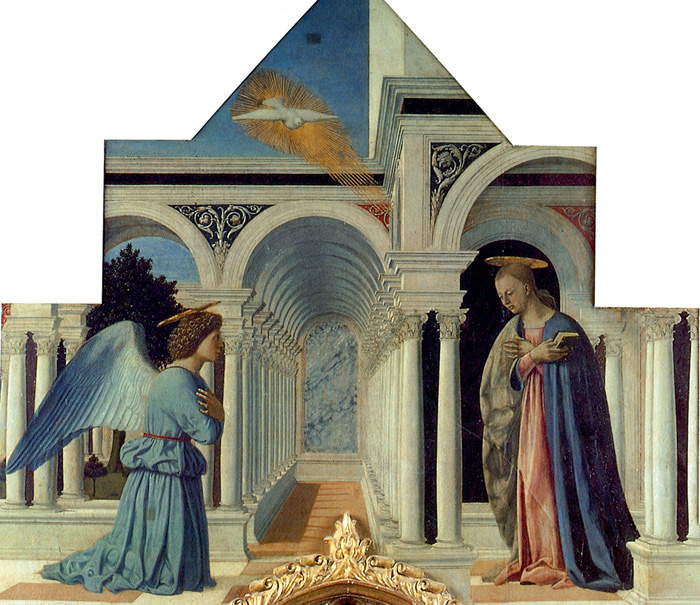

| Piero della Francesca, Polyptych of St. Anthony (c. 1460-1470; mixed media on panel, 338 x 238 cm; Perugia, National Gallery of Umbria) |

|

| Piero della Francesca, Polyptych of St. Anthony, TheAnnunciation |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Annunciation (c. 1472-1475; oil and tempera on panel, 98 x 217 cm; Florence, Uffizi) |

|

| The Angel of theAnnunciation by Leonardo da Vinci |

|

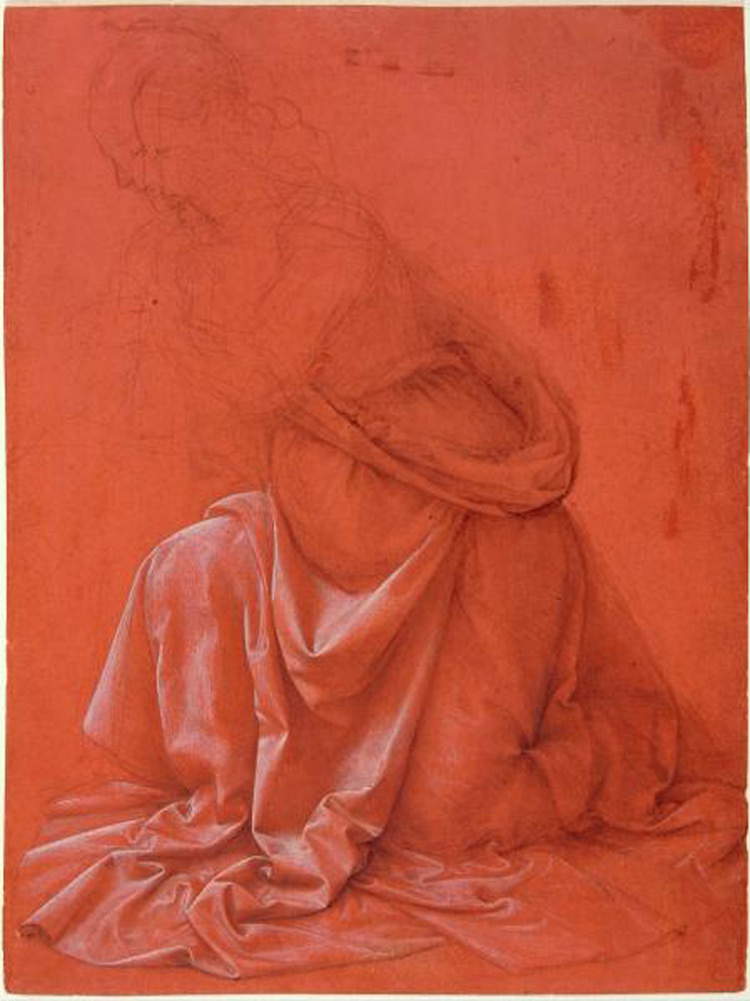

| Leonardo da Vinci, Study of drapery (c. 1473-1480; drawing in white lead and metal point on paper, 257 x 190 mm; Rome, Istituto Centrale per la Grafica, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe, Fondo Corsini) |

The Urbino painter absorbed the lesson of the artists he wanted to refer to in setting up a composition that, in accordance with his intentions, should be devoted to harmony and movement, and go in search of “relievo,” or sculptural effects: “then diligentia e vago colorire / cum tout i termini suoi e varij distanzi / moventia de disegnio e fa stupire / qualunque i scorti suoi vede e remira / che inganan l’ochio e l’arte fan gioire / le prospective quale drieto se tira / arithmetrica e insiem geometria / e l’alta architectura a lei se invia / cum quanto ingegno in huom possibil sia / reluce e splendende exprime in gran concepti / onde io stupisco i’ nella menta mia. / Insuma quel che molti alti intellecti / nella pictura excelsa hanno dimostrati / riluce in lui cum sui termin perfecti / ne pretermesso ha ancora cum dolci e grati / modi il relievo per che alla sculptura / mostrar quanto idea el cielo e i dolci fati”. Summing up, Giovanni Santi shows his appreciation for artists who employ their ingenuity by resorting to the science of perspective in order to give life and foreshortenings and illusionistic effects “che inganan l’ochio e l’arte fan gioire.” And Giovanni Santi, with the means he had at his disposal, and looking to his lofty models of reference (not by chance all great interpreters of perspective like Melozzo and Piero della Francesca, extraordinary masters of optical effects like Leonardo, and superb imitators of the real like the Flemish artists), tried to put his intentions into practice in theAnnunciation as well.

Finally, it must be imagined that this way of understanding art would have been transmitted to the very young Raphael (although it must be pointed out that the real contribution of Giovanni Santi’s lesson on the child Raphael has long been debated and is still debated): “Giovanni Santi’s artistic practice (theoretical and imitative),” Butler concludes, “allows us to contextualize very precisely his son’s first approach to the art of painting. In particular, it allows us to understand the latter’s syncretic approach to sources, almost always consisting of the models praised and imitated by his father.” If one thinks of Raphael’s first tests, from the Stendardo della Santissima Trinità to the Pala del beato Nicola da Tolentino, but even if one goes further, it will not be difficult to find references to many of the artists that his father Giovanni had appreciated: certainly, these were largely the painters who had animated the artistic environment of Urbino in the last decades of the fifteenth century, but towards his models the young Raphael always showed that “critical” attitude that had animated his father’s research.

Reference bibliography

- Maria Rosaria Valazzi (ed.), Giovanni Santi.

- "Da poi... me dette alla mirabil arte de pictura, " exhibition catalog (Urbino, Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, from November 30, 2018 to March 17, 2019), Silvana Editoriale, 2018

- Paolo Cova, Giovanni Santi in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, volume 90, Istituto Treccani, Rome, 2017

- Kim E. Butler, Giovanni Santi, Raphael, and Quattrocento Sculpture in Artibus et Historiae, vol.

- 30, no. 59 (2009), pp. 15-39

- Lorenza Mochi Onori (ed.), Raffaello e Urbino: la formazione giovanile e i rapporti con la città natale, exhibition catalog (Urbino, Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, April 4 to July 12, 2009), Mondadori Electa, 2009

- Fermo Giovanni Motta (ed.), Giovanni Santi .

- Atti del convegno internazionale di studi (Urbino, 1994), Mondadori Electa, 1998

- Ranieri Varese, Giovanni Santi, Nardini Editore, 1994

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.