Tradition and modernity: the Polyptych of Mercy by Piero della Francesca

On June 11, 1445, the ancient company of Santa Maria della Misericordia of Borgo San Sepolcro commissioned Piero della Francesca (Borgo San Sepolcro, c. 1412 - 1492) to paint a panel to be placed in the confraternity’s church, obliging the artist to use woodwork that had already been entrusted years earlier, in 1428, to a local carpenter, Bartolomeo di Giovannino d’Angelo: this is the date from which the story of the Polyptych of Mercy, the earliest documented work by Piero della Francesca that has come down to us, begins. The contract was particularly detailed: the company, whose monogram we see in the two panels in the corners of the polyptych, in the lower register, required Piero to carry out the gilding in “fine gold” and to color the figures with precious colors, “especially ultramarine blue.” The artist also pledged to deliver the work within the space of three years. In the end, the company had to wait as long as twenty to see the work completed: in between, even an official reprimand to the artist in 1454, nine years after the commission and an all too patient wait by the brotherhood. The brethren were also content with the work being done with some recourse to workshop assistants, although the contract specified that every part was to be done by the hand of the master. And so, in 1467, twenty-two years after the commission, the balance finally came to the artist, who had taken so long to complete the work because of the many commissions and commitments that had kept him busy all those years (and, of course, also because his interest in the Polyptych of Mercy, which can perhaps be considered Piero della Francesca’s most traditional work , had somewhat waned, although he did not lack interesting innovative elements capable of making this work a work of relevant modernity). The ensemble was, however, long overdue, for it was still running in 1422 when Urbano di Meo Pichi, a member of one of the most illustrious and wealthy families of Borgo San Sepolcro, left the company 60 gold florins to pay for a panel to be used for the high altar of the confraternity’s church. By 1430 the woodwork was ready, and the name of the artist who was to paint the panels, the Umbrian Ottaviano Nelli, was also ready, but he never completed the work, we do not know why. The fact remains that, a few years later, the confraternity decided to turn to Piero della Francesca, who had probably already made a name for himself in the undertaking of the Polyptych of San Giovanni in val d’Afra, and thus had evidently been identified as the right artist for the job. He was young, he was local, he was promising-all elements that perhaps guided the confraternity’s decision.

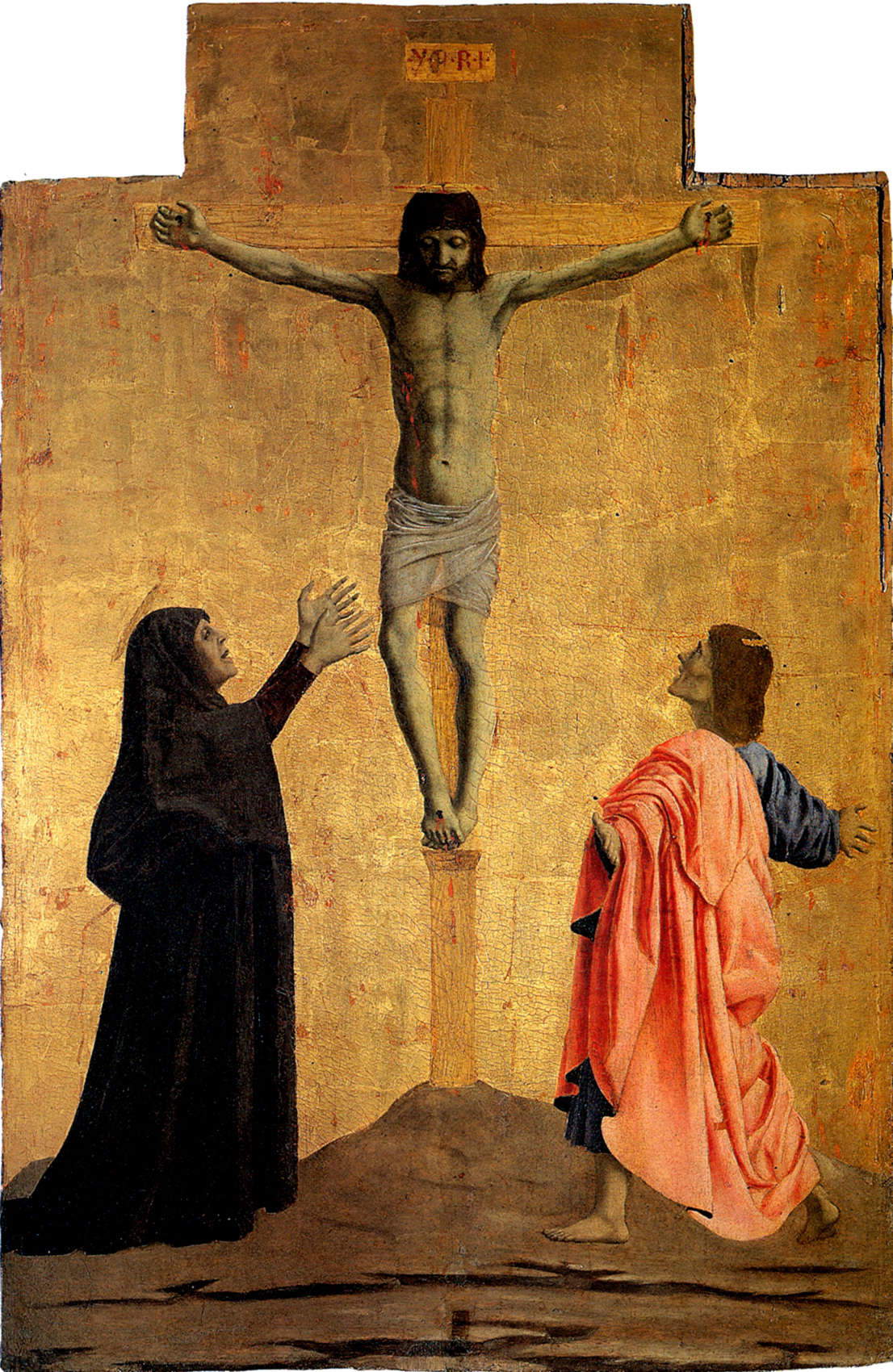

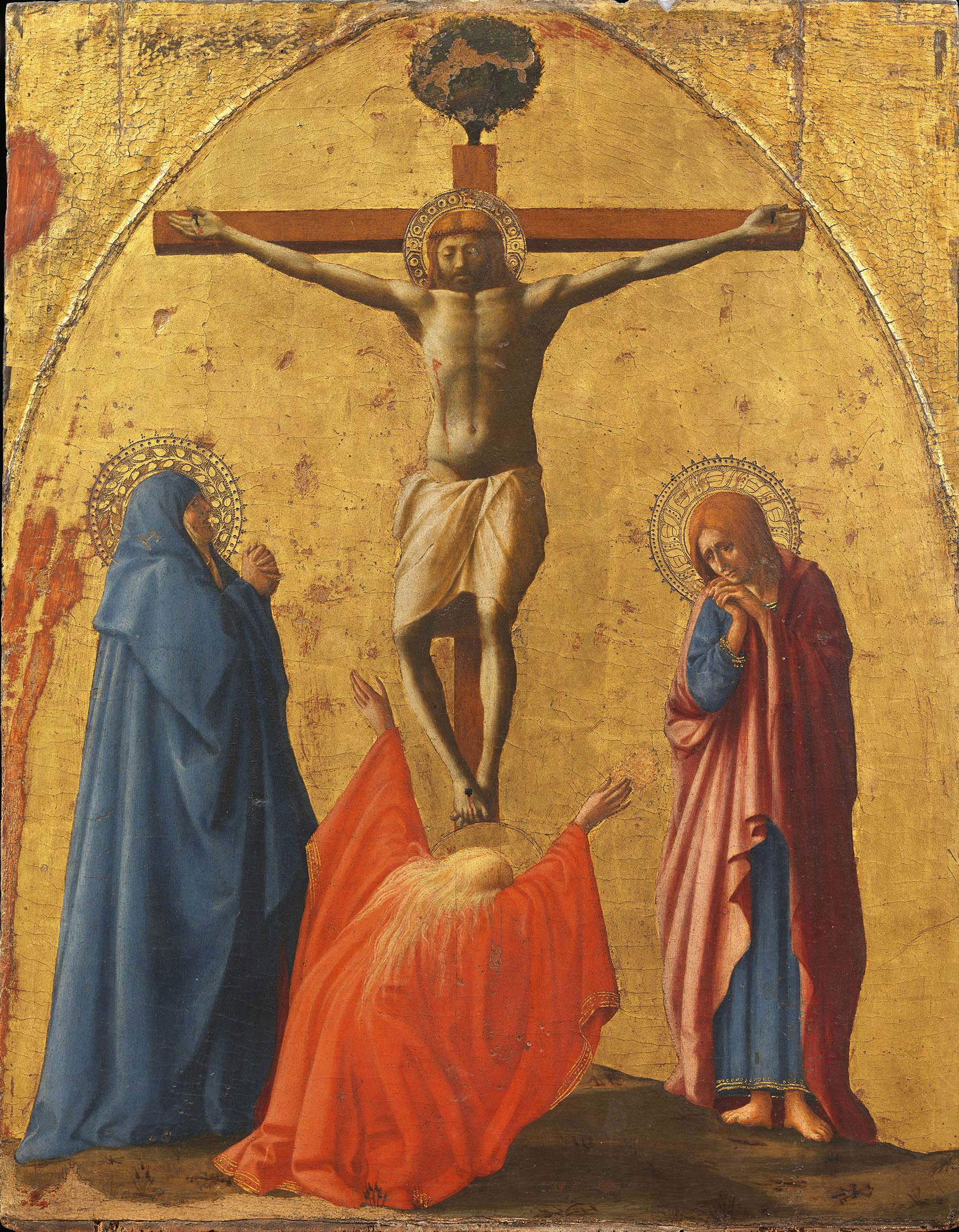

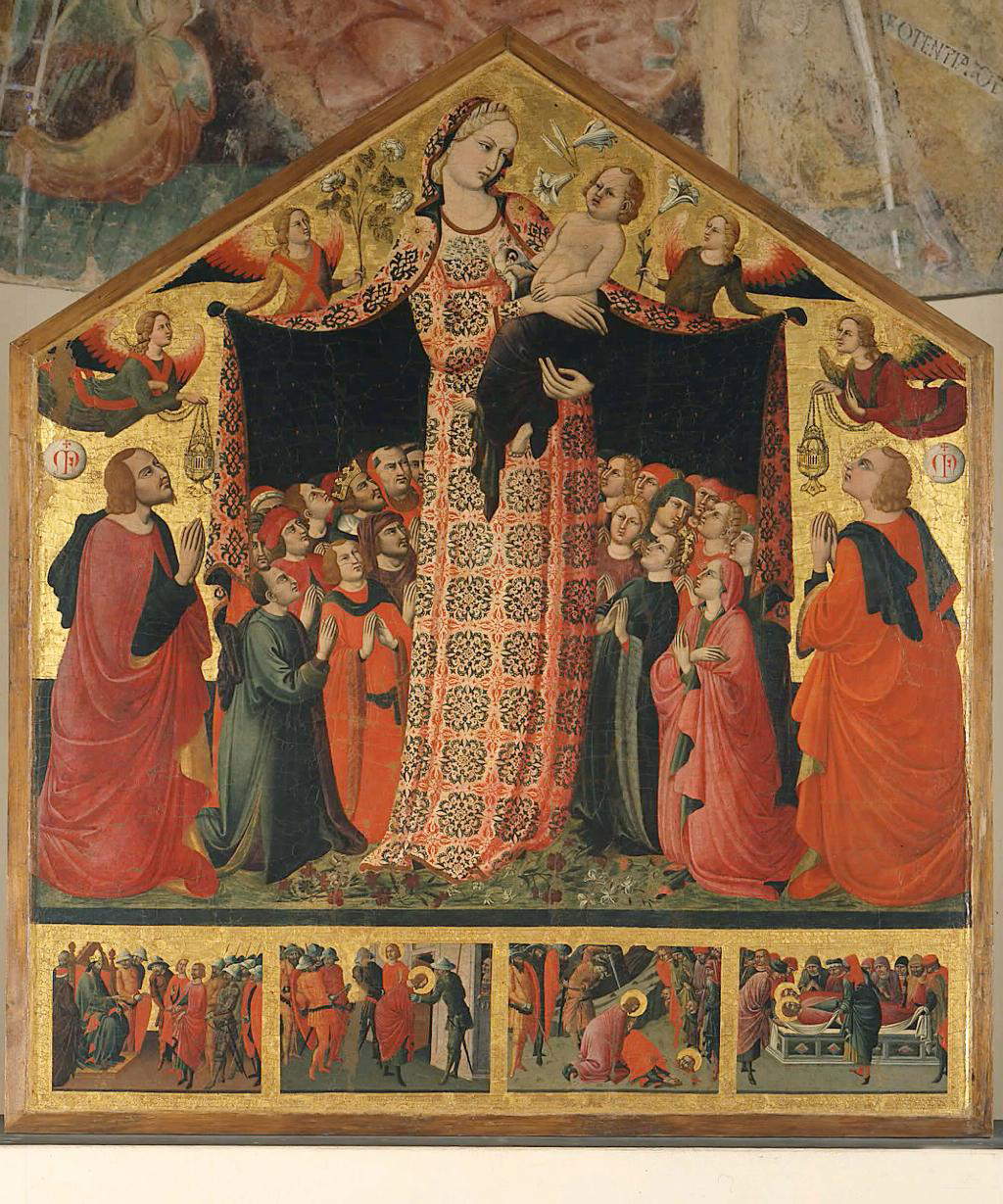

Today we have lost the original frame of the polyptych, so we can no longer see it as Piero’s contemporaries saw it (although we can get an idea: at the Museo Civico in Sansepolcro, where the polyptych is kept today, we see it displayed according to the most likely reconstruction): the whole was dismembered in the seventeenth century, and the woodwork has not survived. The gold backgrounds that characterize all the panels in the ensemble, except, of course, for the predella compartments (here, in fact, it was permissible to paint the background with landscapes), show that Piero’s patrons must not have been particularly eager to keep up to date with the novelties of what we now call the “Renaissance.” in Florence, in those very years, several artists were experimenting with innovative solutions for altarpieces, which included the abandonment of the rigid division into compartments typical of medieval art, as well as the abandonment of gold backgrounds. In Borgo San Sepolcro, the echo of these innovations had probably not yet arrived, or had not aroused enthusiasm. A situation common to much of Italy at the time, after all: it should not be forgotten that Florence, at the time, represented theavant-garde, if it is permitted to use that term. Piero della Francesca’s work must therefore have had a traditional arrangement. In the central compartment, the artist painted Our Lady of Mercy who under her mantle protects the members of the confraternity, while in the side compartments here are in order St. Sebastian, St. John the Baptist, St. John the Evangelist and St. Bernardine of Siena. In the cymatium is a Crucifixion, with tablets depicting St. Benedict, the Announcing Angel, the Virgin Annunciate and St. Francis on either side. In the side pillars, three saints on the left (Jerome, Anthony, and Arcane) and three on the right (Augustine, Dominic, and Aegidius), with the coat of arms of the Company of Mercy below. Finally, in the predella, the Oration in the Garden, the Flagellation, the Deposition in the Tomb, the Marys at the Tomb, and the Noli me tangere.

The gaze is inevitably drawn to the broad figure of the Virgin who embraces the brethren with her mantle, almost as if creating a large dome to protect them. The Madonna is fixed, solemn, hieratic, Byzantine; the proportions still follow the hierarchical canon of medieval art: that is, the more important the figure, the larger her scale. And this despite the fact that Piero is both painter and scientist, a perspective theorist who nevertheless accepts a violation of natural proportions. And then, that sculptural form is “a sign of new times,” Lionello Venturi observed, its volumes innovatively solving the problem of inserting the figure into space inevitably speak the language of Renaissance art, with the result that the central compartment of the Polyptych of Mercy today appears to us as an admirable synthesis of past and future, ancient and modern. “It opens the great blue mantle, thus revealing its great scarlet reverse and forming, at the same time, a very wide pavilion to contain the devotees, to protect them,” wrote Roberto Longhi commenting on the work. “They kneel around the vermilion shaft, arranged in a free hemicycle, tranquil under the tower above them of such an African giantess, secure indeed under the colonnade of folds. In the great structure of this Virgin is the sign of a new and impassive humanity, but also of a new architecture, for in the compartment of this mantle already one breathes the air of a Bramantean niche and the School of Athens. Whoever considers for a moment the meaning of such a structure bestowed on the Virgin of Mercy will come to the conclusion that within this category of crystalline measure Piero was paid and intent on including humanity as well as divinity. [...] There is no doubt, we mean, that, out of deference to the supreme feeling of divinity, Piero left place and principal dimensions of the Virgin according to the concept of the fourteenth century, and that, after the free symmetry of the Baptism, he deliberately subjected himself to the central and rhythmic symmetry, easy to assume symbolic value. The gold imposed by the devotion of the brethren came to accentuate that meaning still further, and, in short, the whole work results in an arcanely iconic and, even, idolatrous severity that seems to make use of that sense of unbreakable stability that the Egyptians chose as a symbol of eternal duration.”

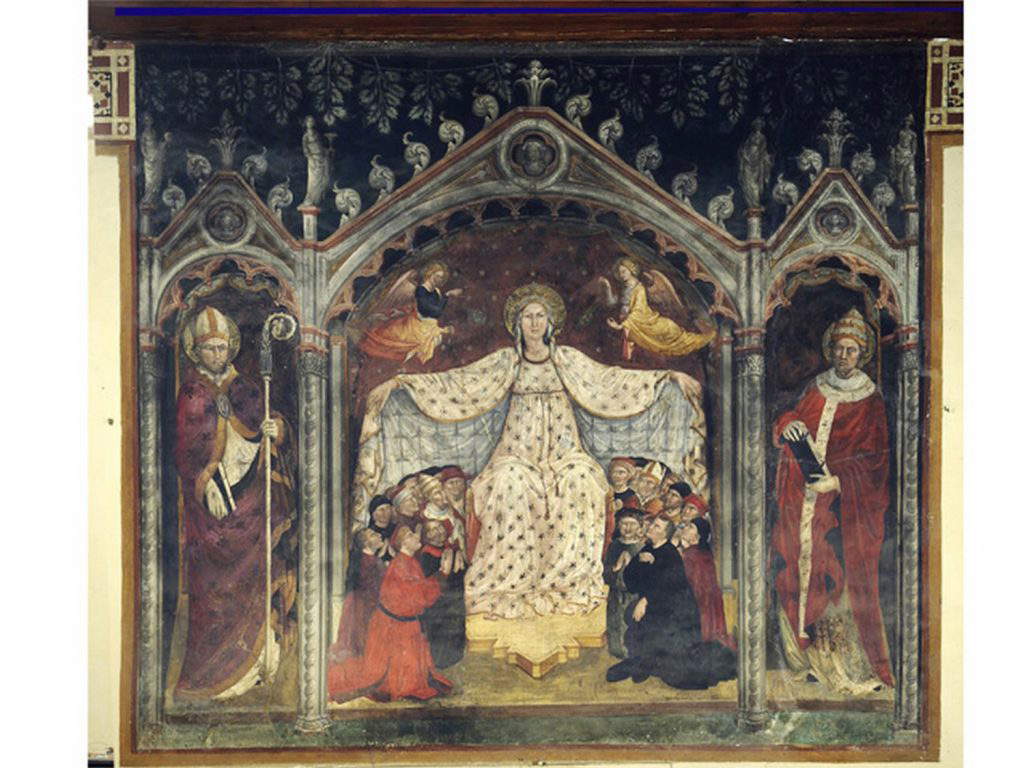

Piero treats space in a unified way. There is gold on the background, yes, but it becomes a pure convention: for the artist that background must be a credible space, and it is for this reason that any decoration disappears from the background, and the gold becomes pure light. The figures are thus all illuminated by a natural light coming from the right, there are no punctuation or other concessions to any decorativism that would have made the final result less modern, and even, the fur on the edge of the Virgin’s mantle shines realistically from the golden light that illuminates it. We are not yet talking about a Piero della Francesca in his full maturity, or at least not for all the scenes (it will be recalled that it took the artist some twenty years to complete the work): as early as 1922, Adolfo Venturi noted that the “multifaceted construction of the form, somewhat rough and wooden,” was reminiscent of the works of Andrea del Castagno. This applies first and foremost to the saints on the left, those that Piero presumably painted first, the most Masaccesque of the whole: but since his destiny, as Antonio Paolucci had written, was not that of the “Masaccio reborn,” Piero, within a few years, went from the more angular figures on the left to the more outstretched ones in the right-hand compartments until he reached the central panel, painted perhaps when the work was in the home stretch. There is thus in the Polyptych of Mercy as much Piero masaccesco of the beginnings (there is also the possibility of direct comparison: compare the Crucifixion of the cymatium with the one Masaccio painted for the Carmine Polyptych), as much as the concrete evidence of that new world that would later enter his art with the works of his full maturity, a world that is revealed here above all in the monumental, geometric conception of the figure of the Virgin that appears as a sort of great dome protecting the faithful below. Piero thus renews an iconographic subject that had a long history and counted several examples near Borgo San Sepolcro: for example, the Madonna of Mercy that Domenico di Bartolo had painted for the hospital of Santa Maria della Scala in Siena, or the one by Niccolò di Segna painted for the church of San Bartolomeo in Vertine, near Gaiole in Chianti, and now in the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Siena, and then again the Madonna of Mercy by Parri di Spinello at the Sanctuary of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Arezzo (the same artist had previously practiced the same subject in a panel now in the Museo Nazionale d’Arte Medievale e Moderna in Arezzo). Compared to precursors and contemporaries, Piero also stands out for having reduced the number of the faithful who find welcome under the Virgin’s mantle, and given also their marked individual characterization (albeit in the idealistic-geometric impetus that distinguishes the art of the painter from Biturgia since his beginnings), it cannot be ruled out that we can trace in those faces the portraits of precise members of the confraternity, impossible, however, to identify. It must be said, moreover, that in the man to the left of the hooded figure a self-portrait of the artist has often been recognized.

Piero della Francesca succeeded in blending tradition and innovation in a work intended not only for the confraternity of Misericordia, but for the entire community of Borgo San Sepolcro, and which was therefore meant to be almost a sort of totem for the population of the small town in Valtiberina: St. John the Evangelist is the patron saint of the town; St. John the Baptist, depicted at the right of the Virgin, is instead the patron saint of Florence, on which Borgo San Sepolcro at the time depended; on the pillars are depictions of Saints Arcano and Egidio, who, according to legend, founded the town bringing to the Holy Land several relics including a stone from the Holy Sepulcher (hence the name), and the three scenes of the predella (the central one and the two on the right, which follow the two on the left) revolve around the events that occurred at Christ’s tomb after the Passion (the deposition in the tomb, the episode of the Noli me tangere , and that of the Marys and the angel announcing the resurrection to them). And because a community cared for the needy, Piero della Francesca’s polyptych does not lack iconographic elements related to its destination, the church of the hospital run by the Confraternity of Mercy: St. Sebastian, for example, was the saint who protected against plague and disease, while St. Bernardine was the one who, in the 15th century, had helped spread the cult of Our Lady of Mercy (it could therefore be said that he in fact worked to comfort the sick). The Virgin’s brooch and crown, as well as the veil, identify her as the Queen of Heaven who, in this case, intercedes with the confraternity by offering shelter to its members and, consequently, to those who were cared for in the hospital they ran. Claudia Cieri Via gave a particular reading to the image of the Virgin: its monumentality, of Byzantine ancestry according to the scholar, denotes its “value as a tabernacle-temple to which is linked the symbolic meaning of Ecclesia,” and the Virgin becomes “mediatrix and protector towards humankind,” also on the basis of some elements that would find theological parallels (for example, the Madonna’s firm posture finds references in Albertus Magnus, who speaks of ’a Mary “rigid as a column” because “she was never inclined by sin, but was always upright,” or her placement between John the Baptist, forerunner of Christ, and John the Evangelist, the author of theApocalypse where the Virgin is Ecclesia). And then, the predella scenes with episodes related to the limitations of men in recognizing the divinity of Christ, linked to the theme of incarnation. Thus, not only “a purely devotional purpose, but also a doctrinal one, sensitive as much to the presence of tradition and the Eastern Church as to the progressive shift from Mariology to Christology.”

Over the centuries, the Polyptych of Mercy has had a rather troubled history. In 1634 it was moved inside a new wooden altar, made by the Binoni brothers, and was placed in the center of the church. Then, when the church was converted into a new hospital ward in 1789, Piero della Francesca’s ensemble was dismembered, and the panels arranged in no particular order. The panel with the Madonna, moreover, was not even exhibited to the faithful, but was displayed only at special ostensions. A first recomposition took place in 1892, performed by restorer Giuseppe Parrini, after which, in 1901, the polyptych was given to the Civic Museum of Sansepolcro, where the work is still preserved. Recently, between 2007 and 2010, the polyptych was restored (without being moved from the museum: the intervention was carried out on site) by the Superintendence of Arezzo, with material execution by Rossella Cavigli and Fedele Fusco for the pictorial film and Andrea Gori for the wooden support, and under the direction of Paola Refice. Precisely as a result of the campaign of studies conducted on the occasion of this restoration, aimed at fixing some conservation problems that had emerged as a result of analysis, it has been possible to understand the original arrangement of the Polyptych of Mercy, and some important elements that make us understand Piero della Francesca’s modernity have been recognized with abundance. First of all, the use of preparatory drawing, which, Roberto Bellucci and Cecilia Frosinini have written, “had many functions of a design type, which therefore always define it as pertaining more to the intellectual sphere than to the merely practical one.” among the functions, “that relating to the determination of the relationship between the gilded background and painted figures, that of the determination of the measurements of the figures with respect to space and in a reciprocal relational measure, that necessary to provide indications relating to the pictorial drafting (such as partitions of light and shadows, creations of preliminary volumes, etc.)”. And then, the study of drapery that Piero fine-tuned through the use of mannequins, also attested to by Giorgio Vasari (“Usò assai Piero di far modelli di terra, et a quelli mettere sopra panni molli con infinità di pieghe per ritarli e servirsene”): like many other artists of the time, Piero della Francesca used to dress mannequins with wet cloths to study the folds. However, write Bellucci and Frosinini, “it turns out [...] particularly interesting the strong attestation of this in Piero’s school, so much so that it is possible to think of a distinctive technique of his that is taken up by his pupils.”

The campaign also made it possible to recognize the high level of expertise with which the work was conducted from the earliest stages: no signs of incisions were found, which served to distinguish the areas to be painted from those to be left with the gilding in view. But it was also found that there is no overlap between paint and gold leaf: in order to save money, in fact, gold was not spread everywhere, but only where it could be seen. The peculiarity here, however, is that in the absence of incisions there are also no smudges, that is, there are no areas where the paint, even if in a small part, goes to cover the gold. This is a sign that the gilder, i.e., the craftsman who assisted the painter in laying down the gold leaf, had to do an impeccable job by following a very detailed design, but it has also been hypothesized that it was Piero himself who took care of the gilding, thus without external help, precisely because of the fact that there are no clear signs of the design on the plaster of the preparation.

And perhaps it is precisely in this mixture of high and low that lies the charm of the Polyptych of Mercy. Borgo San Sepolcro was a town of few inhabitants, unaccustomed to seeing important works of art, and the few that were there came from outside. There was never, as in major cities, a guild of artists: the town was simply too small to provide steady employment for artists and artisans in the ancillary industry, as Christa Gardner von Teuffel has observed. Besides, the genre of Our Lady of Mercy was among those most associated with popular worship. The peasants of the Valtiberina recognized themselves in the image of the Madonna. They were convinced that they found shelter under her mantle; they were convinced that the Virgin mediated between them and heaven. Piero della Francesca knows this. He knows very well the history of this iconographic subject and the villagers’ attachment to her. And he knows that he has to follow a traditional pattern, not least because he is working for a small confraternity that would probably not take well to a work that was too driven, too innovative. However, this is not enough to restrain him, not enough to make him desist from the idea of intervening in an established iconographic scheme and transforming it into a solemn yet modern image, an almost scientific, monumental, geometric, almost abstract work. In a watershed between different eras that coexist in a single image. But if the ground is that of the past, the gaze is turned to the future.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.