Tommaso Buldini, the surreal painting of an artist with a prolific subconscious

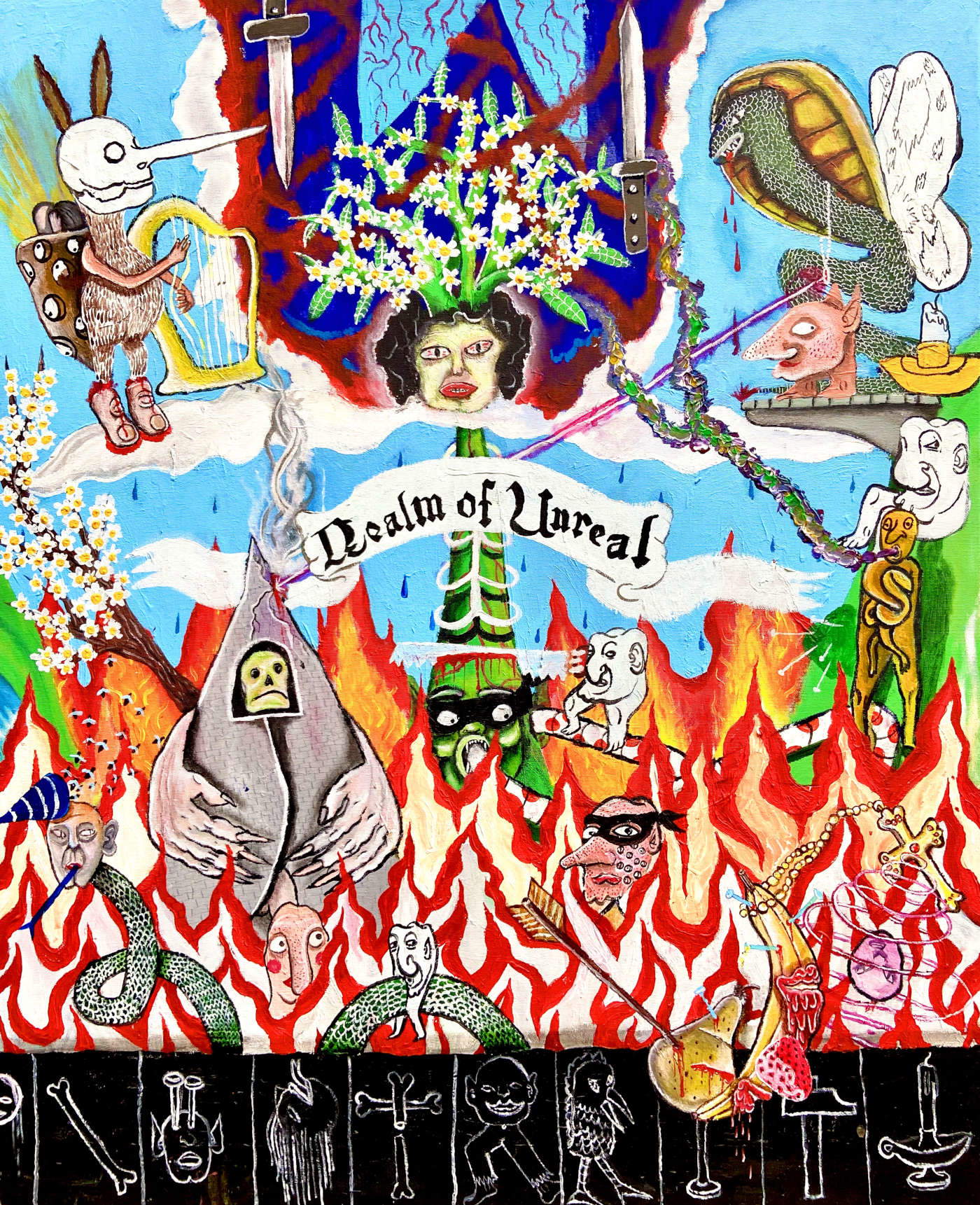

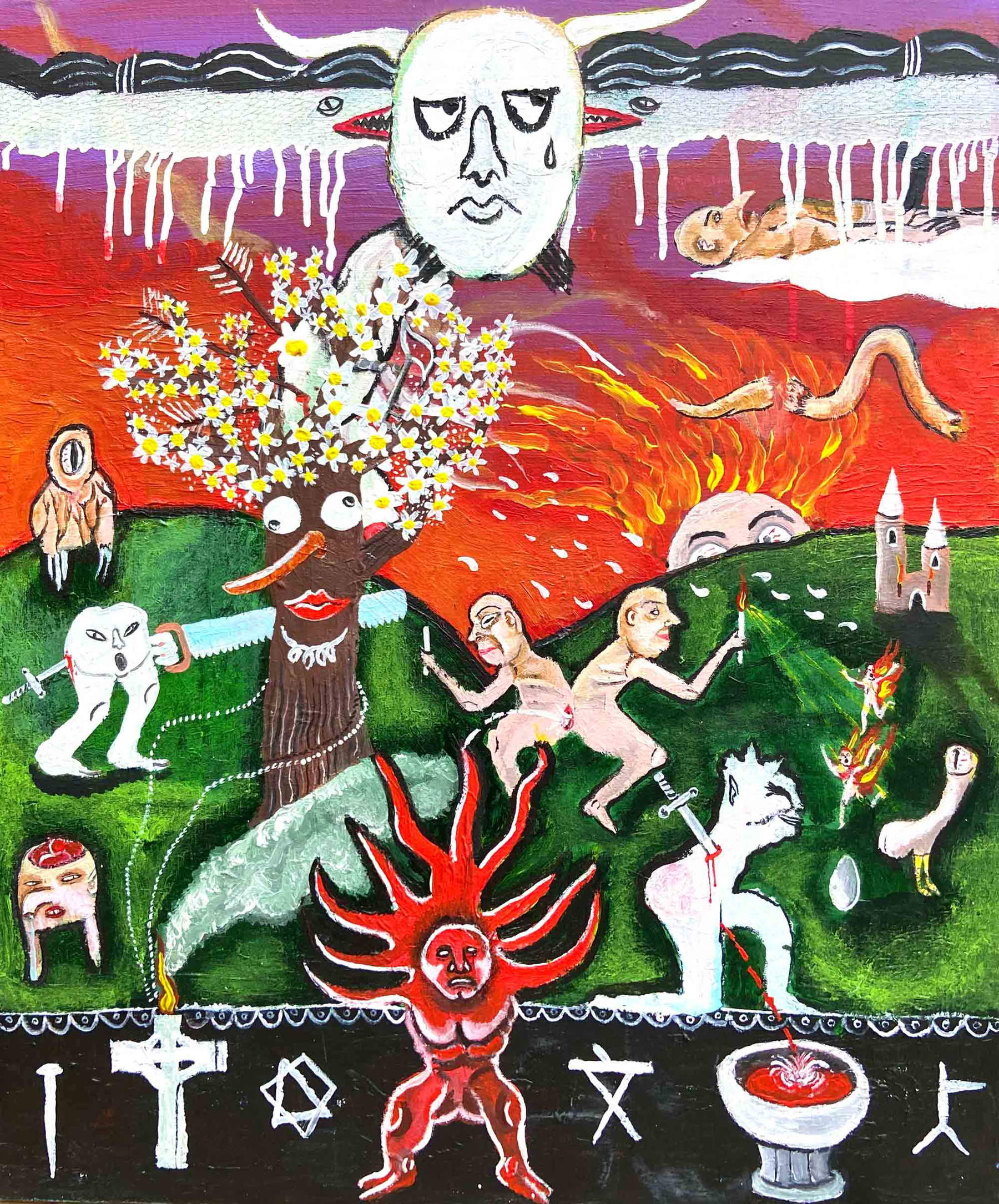

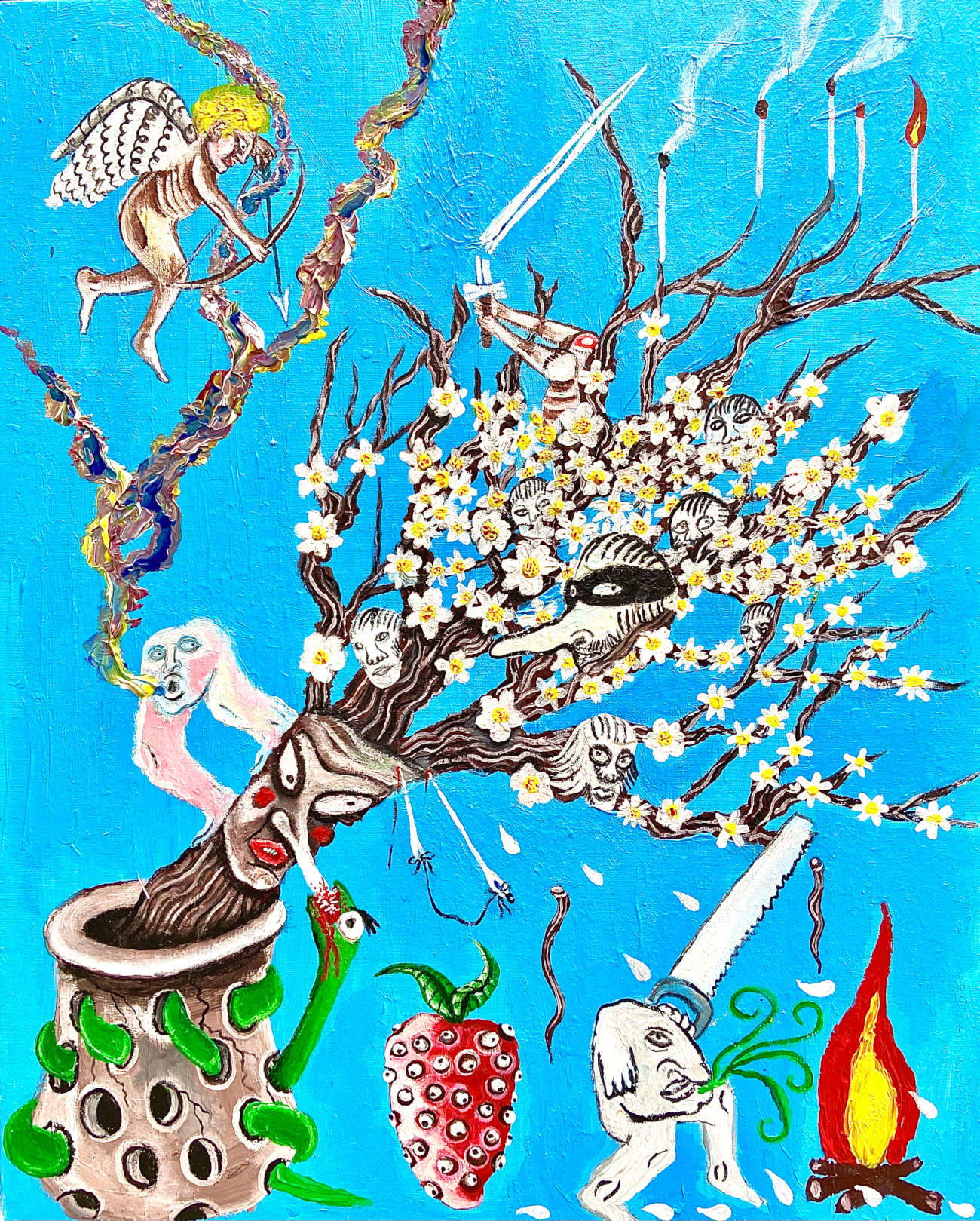

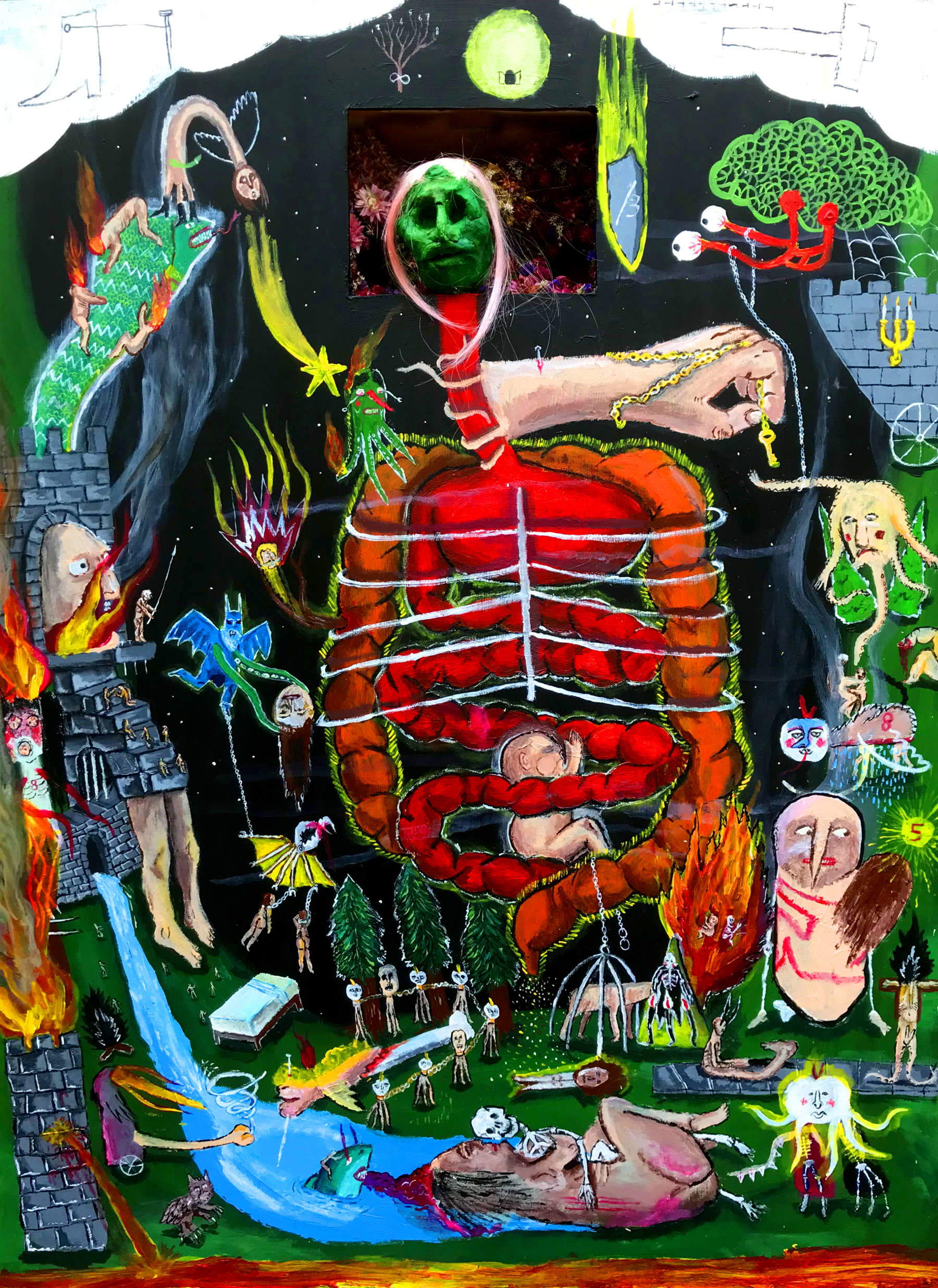

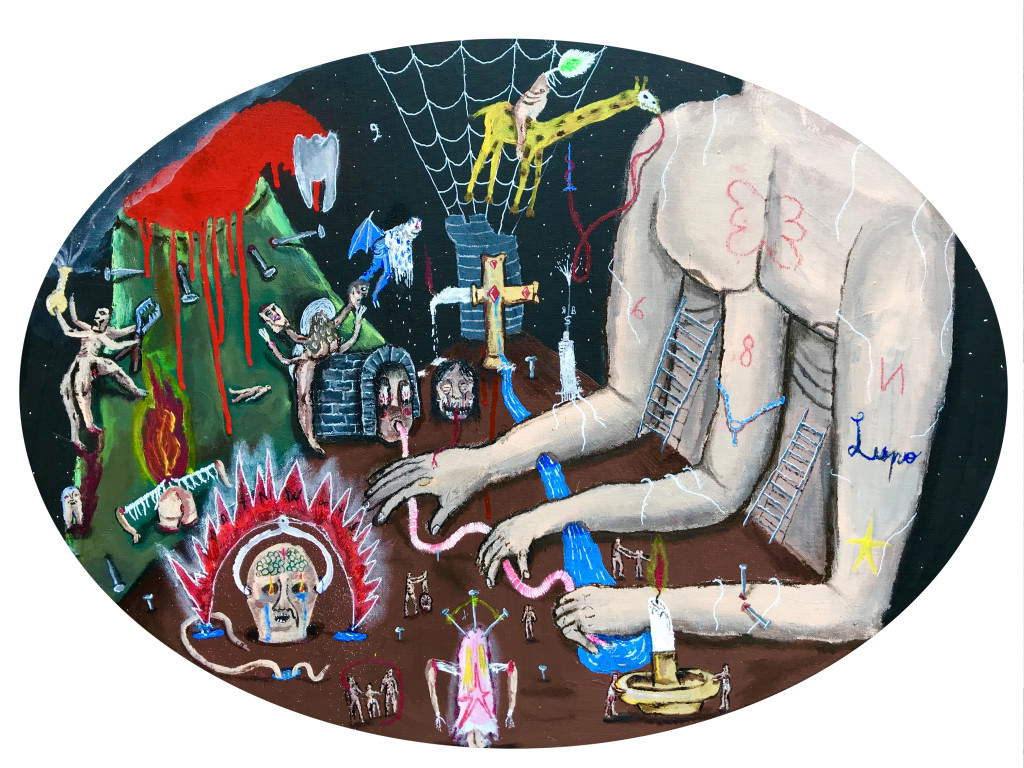

“Anything can happen” in the worlds of Tommaso Buldini (Bologna, 1979), to quote his own words borrowed from the last scene of Fanny and Alexander borrowed, in turn, from Strindberg. “Everything is possible and probable”, even that devils coexist with blemmas (headless beings with eyes and mouths on their bellies or chests), anthropomorphic trees and eyed towers, hooded, little monsters, gloomy harpists with faces-texts of Collodian memory, floating anatomical parts, headless bodies or heads without bodies from whose orifices anything goes in and out (little men, spaghetti, insects, strange animals), intent on actions often meaningless because in these microcosms “time and space do not exist. On a weak frame of reality, imagination spins weaving new patterns.”

Buldini, after studying graphic design in Milan, went on to work as an illustrator, graphic designer and video animator and, at first, approached art by making etchings and Indian ink. “I started drawing during middle school and continued until junior year,” he tells me, on a warm July morning when I had the opportunity to converse with him. “I used to draw landscapes full of characters, violent and perverse things not appreciated and understood by teachers. When I grew up, I was inspired by that same imagery, also influenced by artists related to me such as Giovanni Battista Podestà.” Since 2018, he has been painting on canvas, wood and paper using acrylics and bright colors, bringing to life improbable universes, nightmarish realities in a Realm of unreal consisting of staged uncontrollable impulses, grotesque and disturbing theaters of the absurd in a delirious chaos where everything is calculated and ordered with obsessive minutiae of detail. These brightly hued streams of consciousness, teeming with little creatures and elements spawned by a prolific subconscious, speak a surreal, often unacceptable, hallucinatory language, however, imbued with humor and comic references, with a glimpse of the Middle Ages (I am thinking of Giovanni da Modena to stay in the Bologna hinterland and the fresco in San Petronio where a devil cripples Muhammad), or Bosch’s paintings.

His universes are dense with iconographies that are repeated and often migrate from work to work: trees, demons, bodiless heads, decapitated bodies, but also skulls, eyes, pyramids, hoods, keys, swords (elements, the latter, with symbologies inevitably associated with the world of the occult and esotericism). If we think of the Greek etymology of symbol, συμβαλλω (“symballo”), this refers us to the verb “to put together,” to realities to be filled. Buldini transfers these images from one work to the next with an almost compulsive precision, within spaces where a certain horror vacui is felt, despite the fact that one of his works, almost mockingly, is instead titled Invoking Emptiness. And he explains why: “I invoke emptiness as an inner state. Regarding the images it is about codes to speak to those who can understand,” he confides. “The most beautiful part of these six years of experience is having had the opportunity to communicate without words to people who have since become important in my life thanks in part to a shared language. These figurations refer to archetypes closely connected to a personal experience, or to traumas, family secrets. They speak to people who approach my work and recognize themselves. Ninety percent of the things you see in my creations have to be there; each element is there for a specific reason. I represent something I see, transpose it to the canvas, and only then do I understand what I have done. The pyramid for example, as far as I’m concerned, is a container of something kept inside for a long time, a treasure chest. These are symbols that have an aesthetic that I like but that is untied from esoteric or Masonic references as some have mistakenly interpreted.”

They are works dictated by a kind of automatic painting that look to a certain independent, “over the top” cinema, such as Harmony Korine’s Gummo , from which Buldini himself acknowledges he was emotionally influenced, to early cinema (Méliès comes to mind in some ways with some dreamy Luna Park atmospheres crossed by anthropomorphic moons) and to horror films. Also inspiring Tommaso are those street artists, who have now become internationally renowned names, gravitating around the Bologna area of the caliber of Blu and Ericailcane or exponents of Art Brut (a current, along with that of Lowbrow, into which Buldini’s own work flows) such as the aforementioned Giovanni Battista Podestà in whose works he came across in 2012 during the exhibition Banditi dell’arte at La Halle Saint Pierre in Paris. “Certainly,” he adds, "certain cultural references such as Tommaso Landolfi’s The Tales and particularly Burroughs’ The Island of Cockroaches, The Soft Machine and The Naked Meal but also some of Sartre’s The Wall and Dostoevsky’s The Doppelganger played a key role."

The eye, a fundamental organ when it comes to art, is omnipresent in his works, multiplied, out of place, seeming almost to take on a controlling significance, as if an observer from above did not want to lose sight of us. “Again,” Buldini continues, “it is rather an awareness of what is wrong with me or what has not gone. It is not a Masonic symbol, it is not the eye of power as many have thought, but it is an eye sometimes closed others open, aware of experiences. It can refer to my eye or my parents’ eye. The work is based on my past to those who are still there and those who are no longer there. I allude to episodes that involved my family members as well as me. What I do addresses a personal experience or that of my ancestors: my grandmother used to prepare cadavers for anatomy exercises, and when I was three years old I frequented these faculty corridors filled with skeletons that are still etched in my memory. My great-grandfather, on the other hand, Lodovico Barbieri, director of the Archiginnasio library, was killed under the rubble during the bombings of ’44 that hit the Casaglia building where the most precious books had been sheltered.”

His beginnings were with Rizomi Gallery in Parma, which took Tommaso to Scope Basel in Basel, and then to France where he collaborated with Hey magazine and took part in two group shows at Arts Factory and the P/cass and Ddessin fair. Rizomi also presents his work at the Outsider Art Fair in New York; then it will be the turn of Miami Art Fair and Brussels. With Demoniaco, a “delirious and luciferous” animated painting show sonorized by Colapesce and performed by the duo Plastikhare, he exhibits in Milan and Slovenia. From his meeting with the musician in 2020, a couple of collaborations were born that saw him involved in music videos(Luna Araba, Noia mortale) together with Colapesce himself, Dimartino and Carmen Consoli. Buldini loves experimentation: hence NFT works, dioramas, the set designs of videos for Silvia Malagugini’s Parisian company Nonna Sima, and even the creation of a parapsychological video game with the evocative title Hallucinator. In June this year he concluded his latest exhibition, a two-person show with artist Margherita Paoletti, I Santi dell’anno 2064 at Cellar Contemporary in Trento.

These days , Buldini is working on The book of the Death, “pages, notes and drawings from a diary of death” inspired by the recent loss of his father. “I lost my father three weeks ago,” he explains “I do experiments with India ink, to create a bridge, to externalize deep visions, unconscious worlds.... Even before painting I was always interested in getting in touch with the deceased especially with members of my family to connect with them and reconnect. Regarding death I think there is something left of people who are gone.” This is not the only work Buldini is currently devoting himself to. Right now, he is doing new experiments for an exhibition in Paris and working on “a video project with a projector and two screens with some of his infernal animations, characters reciting mantras and musicians playing”: it will take place in Ravenna in front of Dante’s tomb.

Before saying goodbye, I ask him if there is anything that no one has ever asked him. Thomas doesn’t think twice: his thoughts immediately go to young artists. "I would like to tell them to move forward without being influenced by other people’s prejudices. Because if one has something to say, one should not be afraid to externalize it.... it is important to bare oneself, to have the courage to be oneself; the moment you listen to your solitude, you are no longer afraid of the judgment of a gallery and a critic. In Letter to a Young Poet Rilke, addressing Kappus, writes: ’A work of art is good if it arises from a necessity ... look within yourself, explore the depths from which your life springs; at that source you will find an answer to the question whether you should create.’"

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.