Time discovering the truth: a certificate of solidarity from Domenico Fiasella to Artemisia Gentileschi?

March 4 marked the end of theFiasellesco year, celebrated to commemorate the four hundredth anniversary of the commission of the celebrated altarpiece with St. Lazarus asking the Virgin Mary for protection for the city of Sarzana, entrusted to Domenico Fiasella (Sarzana, 1589 - 1669) on March 4, 1616. The “closing ceremony” of the long series of events commemorating the great Ligurian painter fell to a lecture given by Piero Donati and focused on the artist’s youthful production, from his beginnings in Rome to his return to Sarzana shortly before the fateful March 4, 1616. A topic as topical as ever: this year, in fact, the Fiasellesco catalog recorded an interesting novelty, which was mentioned on these pages in the review of the exhibition on Artemisia Gentileschi in Rome, since in that context the unpublished work was presented to the public.

The novelty, proposed by the Genoese scholar Anna Orlando, is a painting, Time Discovering Truth and Unmasking Deception, attributed precisely to Domenico Fiasella and placed in the years of his stay in Rome: in particular, the art historian proposes a dating close to 1611-1612. There are several reasons that prompted us to devote an in-depth study to this painting: first, because the name of Domenico Fiasella is one of the leading names in seventeenth-century art, and we consider any discovery concerning him worthy of attention (all the more so for the present site, whose headquarters are located very close to Fiasella’s city of origin). Thus, because this would be an important addition to a phase of Fiasella’s career about which there are still many question marks. Third, because this new attribution prompts us, at the very least, to think again about the relationship between the Ligurian painter and the Gentileschi, Orazio and Artemisia. And again because, at least according to the writer’s knowledge, this would be the only case of direct citation of an entire figure of someone else in a painting by Fiasella during his stay in Rome.

|

| The painting attributed to Domenico Fiasella, Il Tempo scopre la Verità e smaschera l’inganno (1611-1612; oil on canvas, 196.5x 142.5 cm; Private Collection) at the exhibition, compared with Artemisia Gentileschi’s work, Danaë (c. 1612; oil on copper, 40.5 x 52.5 cm; Saint Louis, Saint Louis Art Museum). |

Before we begin discussing the painting, however, an appropriate clarification is needed: this small contribution does not pretend to arrive at any firm conclusions (it is not our subject). In order to establish the accuracy of what we are about to present, a proper examination in a scholarly setting, which this site is not, will be appropriate: our intent is exclusively to stimulate a discussion around a work of certain interest, but on which hang several questions that, in our opinion, deserve to be analyzed. The one of greatest interest is probably theoccasion in the context of which Fiasella is said to have created the work: that occasion, according to Anna Orlando, was provided by the trial of Artemisia Gentileschi. In fact, the scholar writes, in the catalog entry for the aforementioned exhibition on Artemisia, that the work could be read “as a tribute and sign of solidarity with the friendly family.” We move, of course, into the realm of pure hypothesis: it is indeed very suggestive to think that Fiasella wanted to express closeness to the violated young woman with such a challenging work (we are in fact talking about a painting that, given its size, it is hard to think of as intended for domestic devotion), but what certainties do we have to confirm an idea that undoubtedly pricks our imagination? It is possible to start with the relationship between Domenico Fiasella and Orazio Gentileschi.

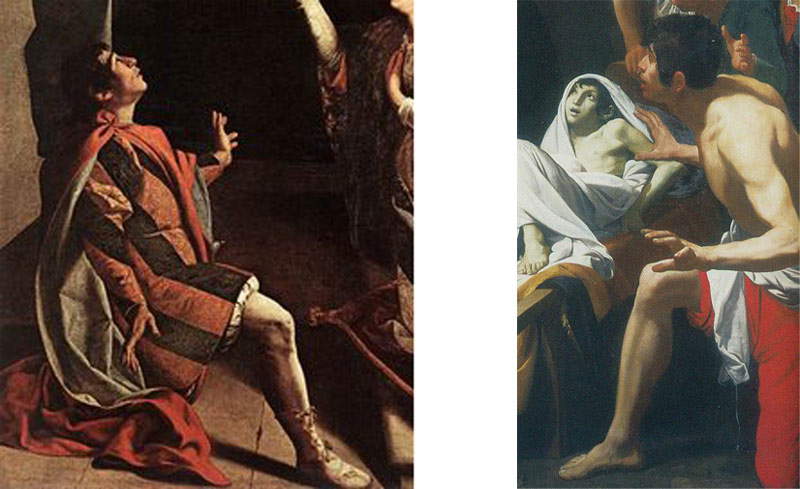

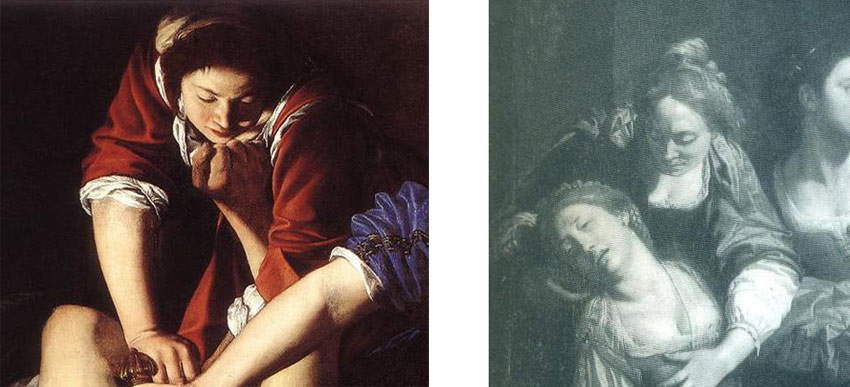

That there had been contact between the two is now taken for granted: there is, if anything, the question of when this frequentation may have had its beginning. In the catalog of the major exhibition on Fiasella in 1990, Donati closed to the possibility of suggestions received during the Roman years, believing that Fiasella “shows himself impermeable in the certain works of the Roman years” to the “early influence of the reformed Gentileschi.” A little less than twenty years later, between 2008 and 2009, on the occasion of the exhibition that Donati was still curating between Sarzana and La Spezia, an essay by Roberto Contini was published in which he left room for the hypothesis that the contacts between Fiasella and Orazio Gentileschi might have begun precisely in Rome: “an authentic Gentileschian red thread runs through in every way - certainly not univocally - the Fiasella of these years.” The years in question are those of the Roman sojourn (or at least those of the latter part of that sojourn in the capital of the Papal States), and Contini identified in several details possible points of contact between the two. For the sake of brevity, we will mention in this article just the proximity that the astonished bystander in the Resurrection of the Widow of Naim’s Son, a painting now preserved in Florida, shows to the Saint Valerian of the altarpiece that Gentileschi painted (in Rome) for the church of Santa Cecilia in Como in 1607. Regarding the relationship with Artemisia, for Contini a sort of quid pro quo was configured such that a work like Fiasella’s Suonatore e cortigiana would constitute a premise for Artemisia’s Madonna col Bambino today in the Spada Gallery, while in Fiasella’s Svenimento della moglie di Pompeo in the Cattaneo Adorno collection, the protagonist’s servant would be descended from Artemisia’s fantesche. If from such references one can imagine that Fiasella also had friendly relations with the Gentileschi family, one must ask to what extent the bond was strong enough to induce the painter to make a striking (and exceptionally modern) attestation of solidarity at the time of the trial (an attestation of which no other examples survive).

|

| Comparison between Orazio Gentileschi(The Angel Visits Saint Cecilia, Saint Valerian and Saint Tiburtius, 1607; oil on canvas, 350 x 218 cm; Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera) and Domenico Fiasella(Christ Resurrects the Son of the Widow of Naim, c. 1615; oil on canvas, 275 x 178.5 cm; Sarasota, John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art). |

|

| Comparison of Domenico Fiasella(A Player and a Courtesan, 1608; Trieste, Lloyd Adriatico) and Artemisia Gentileschi(Madonna and Child, 1610-1611; oil on canvas, 116.5 x 86.5 cm; Rome, Galleria Spada). |

|

| Comparison between Artemisia Gentileschi(Judith and Holofernes, 1612-1613; oil on canvas, 158.5 x 125.5 cm; Naples, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte) and Domenico Fiasella(Fainting of Pompey’s Wife, c. 1625; oil on canvas, 188 x 164 cm; Genoa, Cattaneo Adorno Collection). |

As far as style is concerned, it has already been mentioned how the slavish reprise of the figure of Truth from Orazio Gentileschi’s Cleopatra, in turn imitated by his daughter in her Danae in the Roman exhibition and compared with the painting attributed to Fiasella, constitutes, at least in the memory of the writer, a unique case in the production of these years of a Fiasella who was permeable to various suggestions, but who hardly ever adhered so closely to his own model of reference. It will be appropriate to shed light on this modus operandi as well, which would constitute another major novelty.

|

| Particular with the figure of Truth. |

Turning to more “safe” subjects, one can analyze the most eminently Fiasellesque element of the whole painting: the face of theallegory of deception. If Fiasella’s hand is to be seen in this unpublished work, the latter may be most apparent in such detail: we may encounter similar types in more or less well-known paintings by Fiasella. I have here dabbled in proposing, without any pretension and purely for amusement, a brief overview: from the closest face, that of the prophetess Anna who appears in the Madonna of the Misericordia church in Massa, to the woman who appears in theAchilles with the Daughters of Lycomedes in the Carispezia collections, to a face of higher quality, but still of a type perhaps not so distant, in the Meretrice driving out the prodigal son, a splendid unpublished work presented in a small but very tasty exhibition held in Carrara in 2015 (on the subject there would be, however, some debate: in the catalog it was given as plausible, but not certain). We do not discover today that Fiasella had a certain ability to masterfully render “wrinkled heads and aged breasts,” as the turbulent scholar Luca Assarino acknowledged (although, without detracting from this peculiar skill of his, we grant the Sarzanese that the qualities for which we appreciate him are other), and the piece in the painting on display at Palazzo Braschi fits well with such expertise. These are, however, three works referable to the 1930s-40s (albeit with all the doubts involved): we are therefore far from the Roman sojourn.

|

| Detail with the figure of Deception. |

|

| Comparison of the faces of Fiasella’s works. From left: Madonna and Child, the Prophetess Anna, and Saints John the Baptist and Simeon (c. 1640; oil on canvas, 280 x 169 cm; Massa, Misericordia Church); Achilles and the Daughters of Lycomedes (c. 1630-1635; oil on canvas, 150 x 160 cm; La Spezia, Carispezia Collections); The Whore Drives Away the Prodigal Son (c. 1640-1642; oil on canvas, 230 x 176 cm; Carrara, Cassa di Risparmio Collections) |

To reiterate, in conclusion: there is much to talk about regarding such a painting. Of course: one must consider that the development of Fiasella’s very long career was anything but linear, and that the Sarzana painter often accustomed us to surprises. Can Time Discovering Truth be considered one of these surprises? I turn the question over to those who have been tickled by reading this article and have titles and experience to answer it.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.