On September 5, 1922, Arturo Martini took the membership card of the Fascist Party. It was a choice that the Venetian sculptor would never repudiate, not even after World War II ended, when he stood trial and was suspended from teaching for his adherence to fascism. “Since I was starving with Giolittism,” he had to tell his lawyer on that occasion, “I believed in this movement, that is, fascism, for the betterment of my and Italy’s fortunes. [...] If it then comes to my activity of twenty-five years of sculpture and fascism [...] I answer that this is my trade, that is, as much to serve the devil as the eternal father and I will always do so [...]. The sculptor is like the shoemaker who makes shoes for those who order them; for example, I don’t believe in priests, but I would very gladly make a deposition or whatever. As for the pre-March on Rome enrollment, it seems noble to me, because it was a hope, while those who enrolled afterwards were nothing but cowardly and self-interested opportunists.” So much has been written about the relationship between art and fascism, and if it is necessary to identify the reasons why various artists supported fascism from the very beginning, then Martini’s statements offer an interesting key to interpretation. A “hope”: such was Fascism for so many young people who approached the movement from its earliest hours, in an Italy struggling to rise from the rubble of World War I. Likewise, much has been said about the artists who opposed the regime when fascism was in its twilight years. Little known to the general public, however, are the stories of the artists who opposed fascism from the very beginning.

A premise, however, is necessary: already in the years when Mussolini’s movement was beginning to structure itself, it is possible to observe a certain overlap between the nationalistic claims on which fascism knew how to sink its roots and the gaze that the main and most up-to-date Italian artists of the interwar period turned to the past. In 1919 and 1920 two texts were published that are fundamental for understanding the majoritarian orientations of Italian art of the period: the first was Giorgio de Chirico’s Il ritorno al mestiere , published in Valori plastici, which opened with a polemic against the avant-garde (“By now it is a blatant fact: the research painters who for half a century now have been scrambling, scrambling to invent schools and systems, sweating by the continuous effort of original opinions, of flaunting a personality, sheltering themselves rabbitishly behind the aegis of multifarious tricks, pushing forward as the last defense of their ignorance and impotence, the fact of a claimed spirituality”), and called for a return to traditional techniques, subjects and manners, a restart from the academies, and even corporate models inspired by those of the distant past ("those who will come to be the best and will be considered masters, will be able to exercise control and act as judges and inspectors over minors. It would be good to adopt the disciplines in use at the time of the great Flemish painters."). The second text is Against All Returns in Painting, in which Leonardo Dudreville, Achille Funi, Luigi Russolo and Mario Sironi railed against the “false primitives” and, with the idea that “the true Italian tradition is to have never had any tradition at all”, they were promoting “a new and synthetic plastic construction” that would eschew the pedestrian imitation of the ancient, but also the deformation and “too minute analysis of forms,” the “too fragmentary decompositions of bodies to give all their formal developments.” the text, in fact, laid the foundation for the development of the poetics of the Novecento group, whose first exhibition, in 1923, would be attended by Dudreville, Funi and Sironi themselves.

It is clear that the modern classicism of the Novecento, the revaluation of ancient art beginning with that of the Renaissance, and, in general, all the “returns to the crafts” or, more generally, to tradition, found fertile ground in Italy after World War I, and toward these directions the researches of most of the artists were oriented: there were even those who, like Carlo Carrà (who before the war had also been close to the anarchist movement), even went so far as to abjure their futurist pasts: “Unfortunately, behind the arts,” he wrote in 1920 in Valori Plastici, “there still peeps out the mocking sneer of revolutionary and dissolving mythology. The fact, however, that today we speak again of tradition and classicism has its cautionary significance as well. It has been more than half a century that subversive art and aesthetics have been all but administered. Now, however, after having been sensual and materialistic, the artist is again becoming mystical, or, what is the same, idealistic Platonic discoverer of forms.” Already in 1922, then, would come the first proposal of an art “that fascism should spread and make triumph,” and that Ardengo Soffici, in one of his articles(Il fascismo e l’arte, published in Gerarchia), defined above all by negation: an art, therefore, that avoided the imitation of foreign things, that rejected the most driven modernity (the one “logically glorified by Russian Bolshevism”), but also the pedestrian emulation of ancient Italian art. A modern Italian art, in essence, like that of the Novecentisti.

This then, in extreme synthesis and trivializing, was the context, and these were the reasons why fascism found very few opponents among artists in those years, although the artists’ adherence to fascism was neither immediate nor even taken for granted: it was, if anything, progressive and diluted, and had to be enacted through an assimilation that the regime was forced to pursue programmatically and in stages. There was, however, alive, present and pulsating an opposition that hardly ever took the form of open contestation and proceeded without coordination and in a piecemeal manner, but which did not fail to make its own, albeit feeble, voice heard, albeit in the context of anItaly governed by a regime that never got to the point of planning a defined cultural model, an Italy that, despite its nationalist afflatus, continued to nurture a lively interest in the literatures and arts being produced on the other side of the Alps. “A kind of tacit pact was created between the regime and intellectuals,” scholar Daniel Raffini has written, “which gave intellectuals a space to maneuver, albeit a small one from the cultural point of view, often in exchange for loyalty from the political point of view. Censorship tended to target people rather than content: those who spoke out directly against Fascist policies were targeted, while those who maintained a lower profile or accepted assimilation to the organs of culture enjoyed greater freedom of action even with regard to issues frowned upon by the regime.”

An early form of opposition, which later resulted in more or less happy outcomes, was that of the journals, according to three modes identified by the aforementioned Raffini: confrontation, compromise, and attempted assimilation. Significant, for example, are the cases of 900 and Solaria, both journals open to Europe, both founded in 1926, and both critical of the regime’s policies, so much so that the first was forced to close after three years of activity, the ’other, on the other hand, experienced a marked split between those in the editorial staff who would have preferred to follow the path of political disengagement, and those who, on the other hand, considered even political action fundamental (Alberto Carocci, founder of Solaria and supporter of the more intransigent line, would later found La riforma letteraria in 1936 and later participate in the Resistance). Singular was the line followed by Giuseppe Prezzolini, who, writing to Piero Gobetti in 1922, hoped for the formation of a “Society of the Apoti” (i.e., “those who do not buy it”), which would promote distance from the fray, from the most fierce contention, from the “average fierce, from the ”current average Italianity“ in favor of intellectual work guided by the goal of ”clarifying ideas, of bringing out values, of saving, above the struggles, an ideal heritage, so that it may return and bear fruit in future times." Gobetti, from the columns of La Rivoluzione Liberale , which he himself founded, responded to Prezzolini on October 25, 1922 by loudly emphasizing that “in the face of a fascism that with the abolition of freedom of the vote and of the press would want to stifle the germs of our action we will form well, not the Congregation of the Apoti, but the company of death. Not to make revolution, but to defend revolution.”

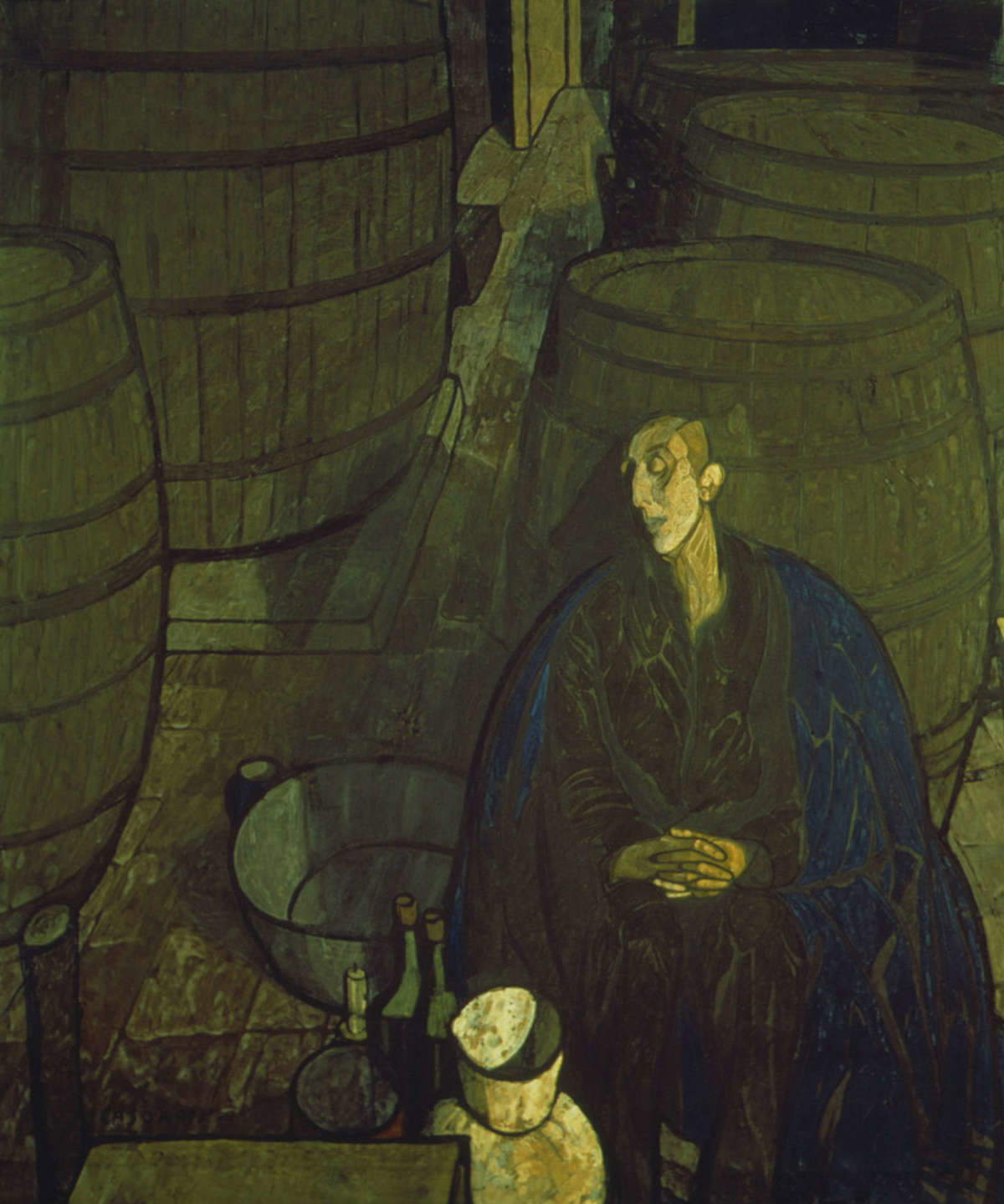

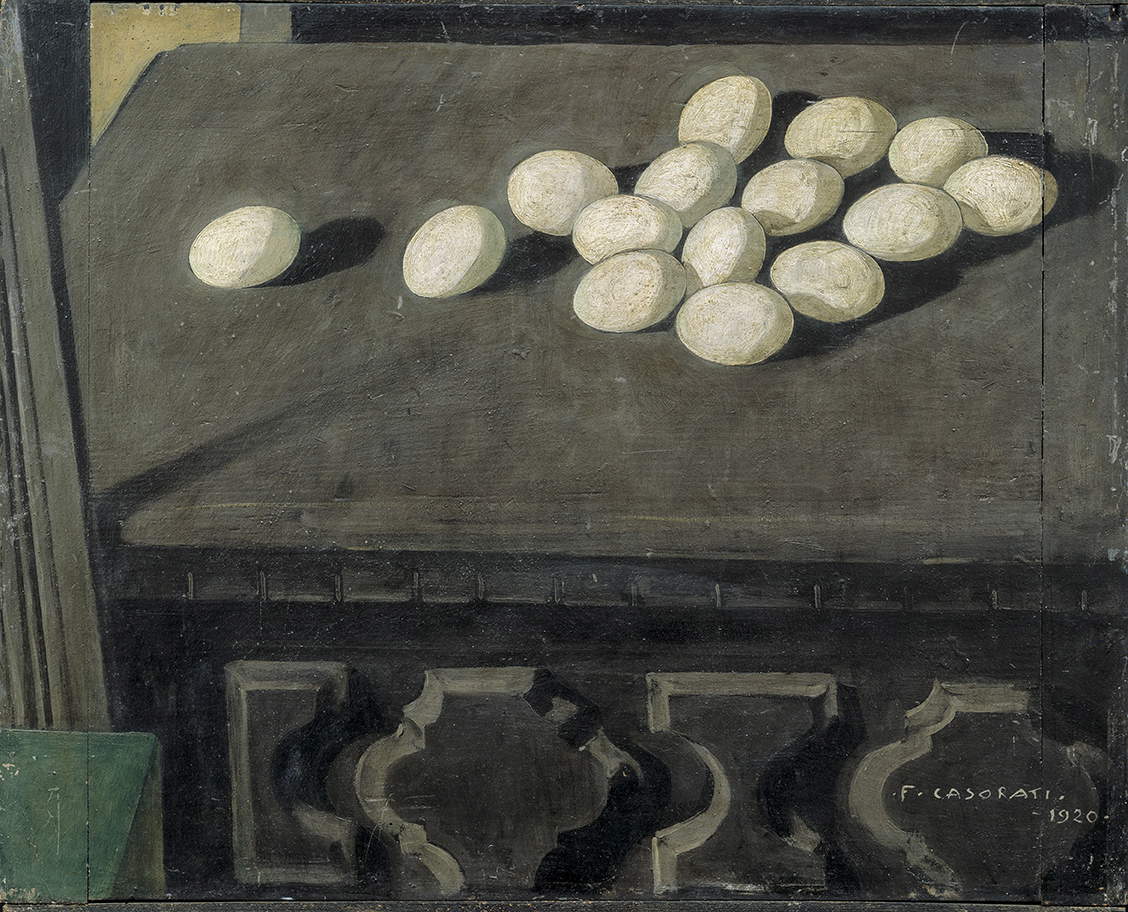

One can identify Felice Casorati as the artist who most and best shared Gobetti’s positions, partly by virtue of the friendship that bound the Novara painter to the young journalist from Turin, a friendship that Casorati would describe, a month after Gobetti’s untimely death, as “tenacious complete perfect.” The two had presumably met shortly after the end of World War I, when Gobetti, just 18, had already founded the magazine Energie Nove and Casorati had approached him looking for an opportunity to exchange new and youthful ideas. Casorati’s art, at those chronological heights, is open to European experiences: if in the years of World War I his painting looks predominantly to the cues of the secessions, after 1920 he will seek a mediation between the analytical approach of Cézanne and recourse to the Italian tradition. Works such as L’uomo delle botti, Uova sul cassettone, and Mattino are from this period, which proposed a different path to a “return to order” than that of Novecento. However, Gobetti considered The Studio to be Casorati’s true masterpiece: the work was destroyed during the fire at the Glaspalast in Munich in 1931, but was replicated by the artist in the 1950s. “The constructive unity of the painting,” Gobetti wrote in his monograph dedicated to the artist, “is all in the spatial sense and in the distances that the painter manages to create by giving all the plastic values a singular freedom and autonomy so that the environment breathes with due breadth. The lyrical movement is kept exclusively in the foreground with obvious danger to the eurythmy, except that in the background the shadows measure it and are in turn enhanced as tonality by the blackness of the background. In this geometric struggle the pause of the gray frame, which has its origin in the center of the picture from the varied play of colored forms that constitute almost the rested and hidden source of luminous variety, usefully intervenes.”

Another front of opposition to Fascism was opened within the broad Futurist cohort: there existed, within the movement, a broad so-called “left wing” composed of artists who had felt the appeal of the October Revolution, and whose conviction was that “the question of education related to machinism,” writes scholar Monica Cioli, should “not concern an elite but the proletariat, the true historical force of the revolution.” Leftist Futurism’s contestation was directed, on the cultural level, at all those art forms that looked back to the past (a contestation, moreover, intrinsic to the Futurist movement), while on the political level, leftist Futurists fought against nationalism, against war, against ’imperialism, ideals to which they contrasted the idea of a constant and unstoppable renewal, of an eternal transformation capable of continuously releasing novelty, ideas, regeneration. Their claims would find shape in 1924 in a pamphlet by Duilio Remondino, Il futurismo non può essere nazionalista (initially conceived as a speech, which, however, he was prevented from delivering for reasons of public order), ch’is both a lengthy attack on Marinetti’s futurism (basically accused of conservatism and therefore opposed as being unfaithful to the movement’s primal instances) and a short political manifesto: “An Italy that still had Rome for its heart, even under the guise of renewal,” we read there, “would in time return to pulse with dominatrix blood that wants for its life superb and despotic blood and slavery, old forms of human life and old concepts that would return to establish the purest passatism, dragging art into the whirlpool of authoritarian arrogance, which would not be slow to become the servant of decrepit conventionalism, the tickler of bored despots [...]. The war is passatist, and the nationalism that promotes it, and strives to support it, comes to be an old idea, an inconsistent movement, an anachronism of the ideal.”

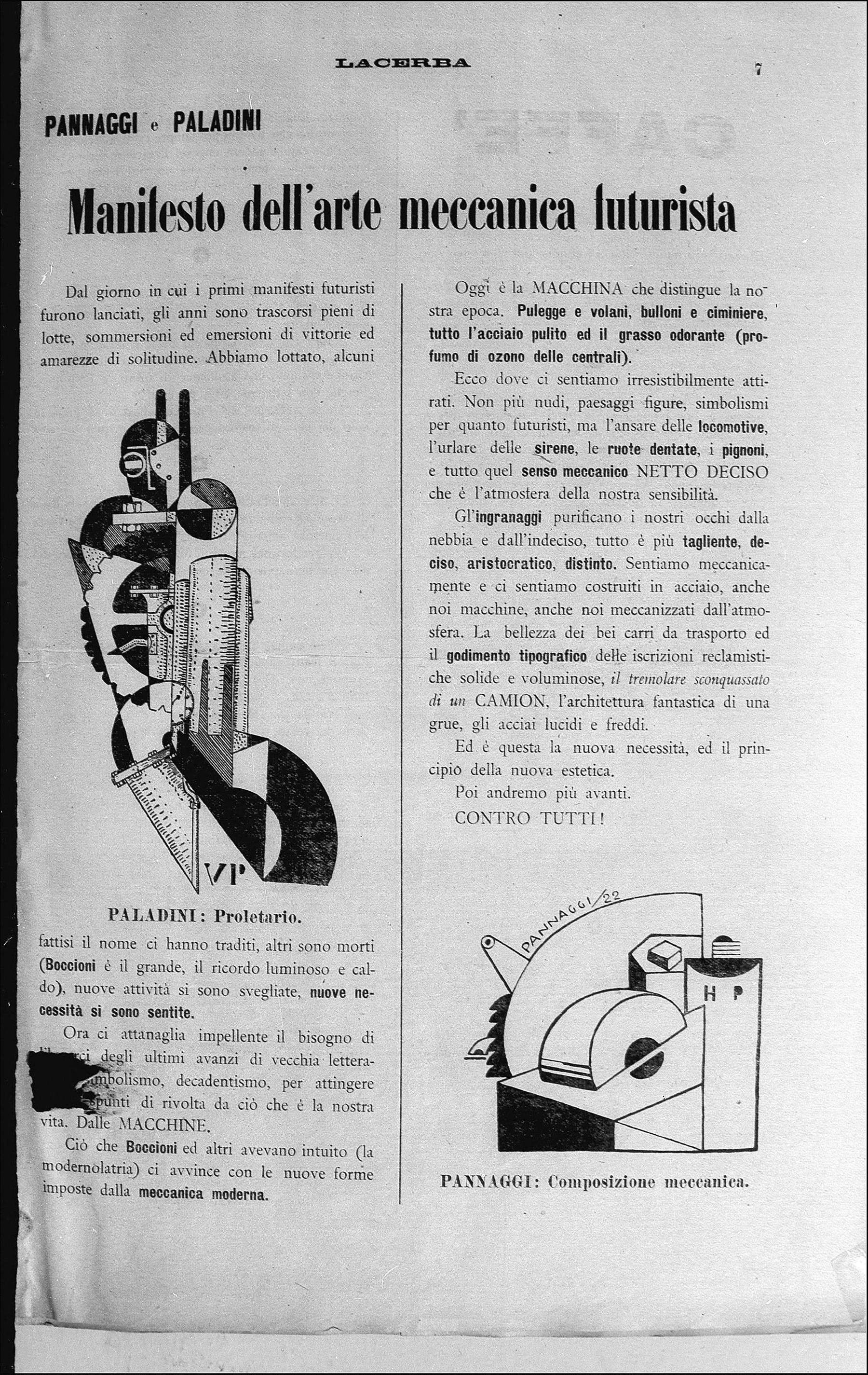

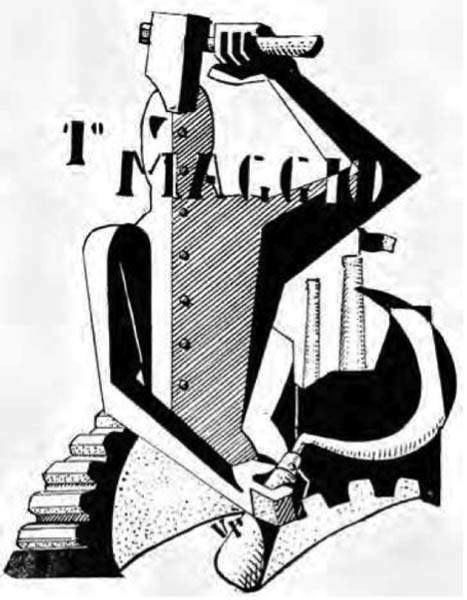

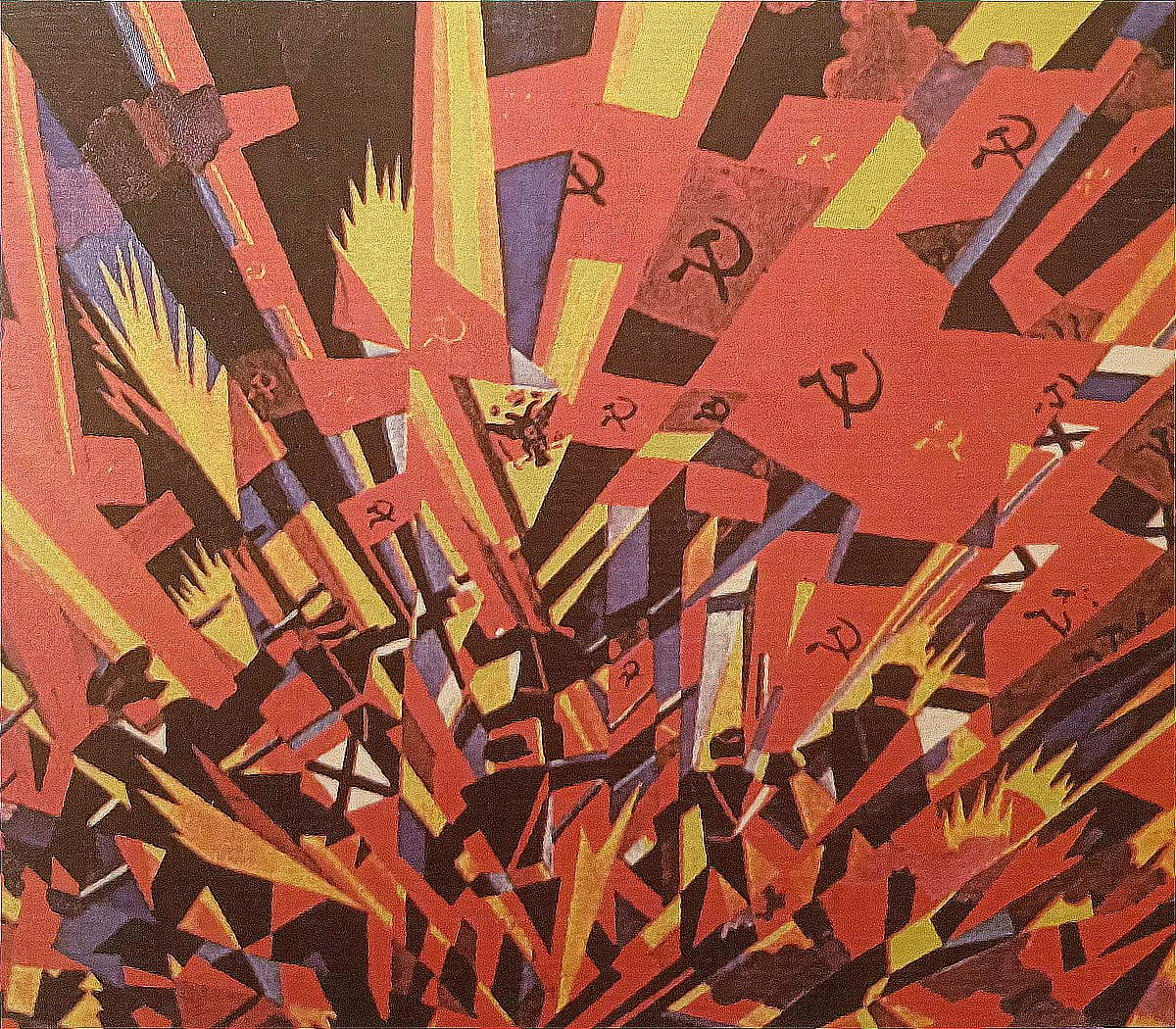

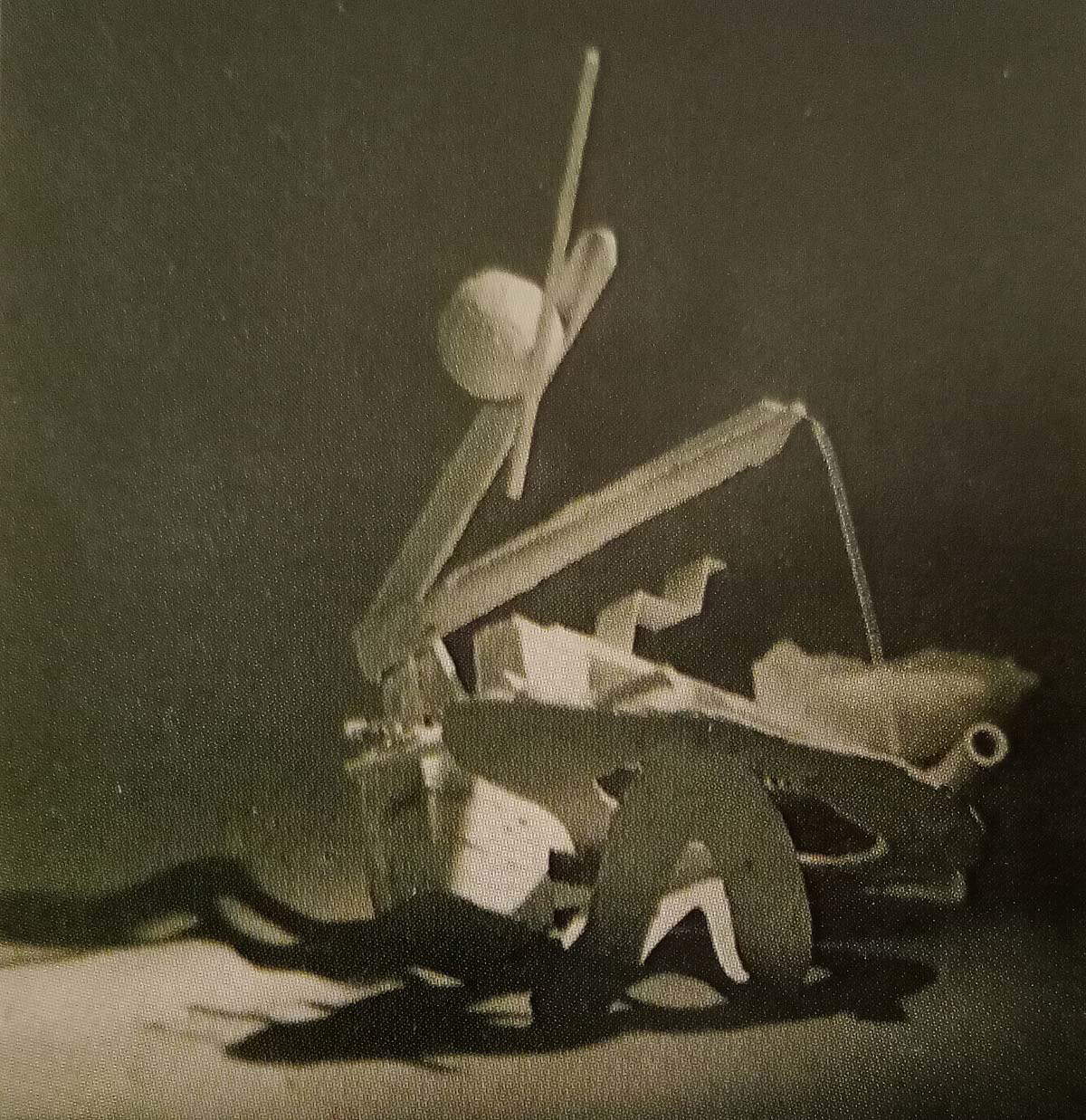

Remondino would later join the ranks of the Communist Party of Italy, and of communist faith would be other leftist futurists, such as Vinicio Paladini, who considered it a duty for the artist to create “for the people [...] new, original scenes for the plays that will be given in the communist theaters, [...] for the most beautiful, luminous and advanced decorations for their rooms” (so wrote a 20-year-old Paladini in 1922 in an article entitled Communist Art, published in the magazine Avant-Garde). He shared his demands with another painter, Ivo Pannaggi, who together with Paladini signed in 1922 the Manifesto of Futurist Mechanical Art, published together with two drawings, a Proletario by Paladini and a Mechanical Composition by Pannaggi: the machine, in the conception of the two Futurist artists, was to be understood not only as an inspirational force in art, but also as a possible source of the revolution of the proletariat, an association that Paladini himself, again in 1922, would make even clearer in an Appeal to Intellectuals also published in Avant-Garde in 1922 (“a marvelous divinity has arisen in our tormented spirits, and it is the proletariat and its machine. We feel that our art by faith in the proletarian and the revolution, can take on the aspect of soul-cerebral constructiveness.”). Pannaggi and Paladini shared the means of expression with other futurists who were instead aligned with fascism, but they moved away from the latter both on the artistic level (the leftist futurists looked a lot to Russian constructivism) and, above all, on the level of content. The same is true for all other leftist futurist artists, from the Friulian Luigi Rapuzzi Johannis, who even went so far as to paint a futurist painting dedicated to the October Revolution, to the Piedmontese Fillìa (pseudonym of Luigi Colombo), who in 1922 wrote a booklet 1+1+1=1 Dynamite. Proletarian Poems moved by the idea of merging the “Red” of the proletarian revolution with the “Black” of the anarchist revolt.

Finally, in this regard, mention should also be made of the sparse, but significant, anarcho-futurist nucleus that intended to follow up on the most subversive ideas of futurism, beginning with the cultural ones (paroliberalism, for example), and could not fail to form a front of opposition to fascism. It was 1919 when Pistoiese anarchist Virgilio Gozzoli started the publications of theIconoclast! an important anarchist periodical that was quite successful but immediately clashed with the violence of fascism: as early as April 1921, squadrists destroyed the printing press whereIconoclasta! was printed and violently beat Gozzoli, who decided to move his activities of opposition to fascism to Paris. However, the life of the “anarchist magazine open to various collaborations,” asIconoclasta! called itself, was now definitely over, despite several plans to restart publication: the last issue remained that of April 15, 1921. TheIconoclast! nevertheless played a leading role in the discussion, which had arisen in 1920, around anarchists’ adherence to futurism, in the context of which the personality of the poet Renzo Novatore, pseudonym of Abele Ricieri Ferrari, a leading name in the La Spezia anarchist nucleus that gravitated around the magazine Il Libertario, founded precisely in La Spezia in 1903 by Pasquale Binazzi and Zelmira Peroni, and which was suppressed as early as 1922 by the regime. Also part of the group was Giovanni Governato, a painter of Piedmontese origins but who soon moved to the shores of the Gulf of the Poets, and who in 1921, together with Novatore himself and Auro d’Arcola (a pseudonym of the poet and journalist Tintino Persio Rasi), founded precisely in Arcola the magazine Vertice, which came out in only two issues. We do not know precisely when Governato joined Futurism, but there is a terminus post quem , which is December 1920, when an article by Marinetti entitled Il pittore futurista Giovanni Governato was published in the magazine La Testa di Ferro, the organ of the Fiume Legionnaires, . In 1921, the artist was to participate in the exhibition Peintres futuristes italiens held at the Galerie Reinhardt in Paris, where Governato exhibited along with Balla, Boccioni, Dottori, Dudreville, Funi, Prampolini,Russolo, Sironi, Baldessari and Depero and where he displayed four works, with programmatic names(1er Dynamisme, 2ème Dynamisme, 3ème Dynamisme, 4ème Dynamisme), but of which no trace remains today, just as we do not know the works he exhibited in 1923 at Ruggero Vasari’s gallery in Berlin, where Governato exhibited together with the Futurists Boccioni, Depero, Dottori, Marasco, Prampolini and Russolo and several international artists, above all Archipenko.

Because of his closeness to Novatore, who was killed in 1922 during a firefight with the Carabinieri while he was wanted for his activities considered subversive, Governato was imprisoned for three months and also suffered a trial, in 1924: Novatore, on the day of his assassination, had a document in his pocket bearing the painter’s name. There remains the transcript of the harangue of Governato’s lawyer Enzo Toracca, whose line of defense centered on the Chromatic’s “drama as an artist,” “which has its origin in the torment of a sensitive and delicate spirit, a burning heart and a fantastic brain ... a rebel certainly, by nature and temperament, against the impositions and dictates of triumphant mediocrity,” and for such reasons, together with Novatore (who could only be described as a man who spread “murky sympathy” around him), he had founded Vertice, a publication to be understood solely as “a symbol of spiritual elevation and ascent, toward poetry, beauty, and glory.” Toracca also quoted excerpts from the pictorial manifesto that Governato had published in Vertice, useful for understanding the way he understood his own art: “Listen: you want to create. Well, to create means to make something not yet existing, with the nonexistent [...]. Creation [...] must be the unconscious made manifest by cerebral instinct, strained in a spasm of sincerity and spontaneity [...]. One must truncate the stupid pretense of understanding the picture. The painting will be creation only when, independently of any representation other than arbitrary and improbable form and color, conceived abstractly and above any intellectual speculation, it reaches such power of fantastic expression, as to produce absolutely new emotions.”

How did the experiences of artists who exercised opposition, artistic or political, to the fascist regime end? Casorati, because of his closeness to Gobetti, was attentive from the very beginning by the regime, so much so that two prominent critics, Carlo Efisio Oppo and Corrado Pavolini, were sent a note warning them not to publicize Felice Casorati and the publisher of his monograph (i.e., Gobetti), as they were “notoriously communist and paid by the foreigner,” on pain of expulsion from the PNF and the magazines in which they wrote. On Feb. 6, 1923, Casorati was also arrested, along with Gobetti, Gobetti’s father and the printer who printed the magazine Ordine Nuovo, on charges of subversion: they were all released shortly thereafter, the arrest being mainly for intimidation purposes, but the circumstance probably should have suggested caution to the artist, especially after Gobetti’s disappearance and thus the interruption of the collaboration between the two. Thereafter, Casorati would avoid any direct involvement with politics, and his “relationship with Fascism,” wrote Francesco Poli, “would be, in later years, very diplomatic, without frictions such as to compromise his participation in major official artistic events, from the Novecento exhibitions to participation in Biennales and Quadrennials.” Casorati’s experience, however, gave rise to a large group of followers, later dubbed as the “school of Casorati,” who organized his first exhibition as early as 1921, which proposed an art, Gobetti himself would recognize in reviewing that very exhibition under a pseudonym, “far from any systematic of academia, born from nothing, remained hidden and limited,” thanks to a “Felice Casorati who remained solitary” who “felt the need to work harder, to help the work of those who could understand it, to prepare practically for the creation of a new taste and a new sincerity of expression.” The “Six of Turin” would have been part of it, artists all united, in addition to their common alumnus at Casorati, by a strong interest in French experiences, among them Carlo Levi, who would later become one of the most committed artists on the anti-fascist front.

Vinicio Paladini, after his promising beginnings, lived substantially on the margins of artistic and political life, and in 1938 left Italy to move to the United States (he would not return until fifteen years later), while Ivo Pannaggi continued his futurist research but stayed away from active political contention: then, in 1942, after his marriage, he moved to Norway (his wife was Norwegian).

Giovanni Governato emerged from the trial acquitted; however, he was kept under strict control by the regime: this circumstance, combined with the dispersion of the La Spezia anarchist nucleus, distanced him from his previous experiences (except for a speech, at the Futurist Congress in Milan in 1924, in which Governato reaffirmed his anarchist position), so that even the Futurist phase of his career could be said to have ended (by the end of the 1920s, Governato would turn to landscape painting of a Symbolist stamp). Little remains, however, of his Futurist work: “his activity as a painter in these years,” Alessandra Gagliano Candela has written, “can count at the present state of knowledge on little evidence: a few suggestions may come from photos from his archive” in which works are seen that reveal “similarities with Futurist works of the 1920s,” as well as from some Plastic Complexes preserved at the Villa Croce Museum in Genoa, exhibited in 1950 at an exhibition at the Rotta Gallery in the Ligurian capital.

These are, however, experiences that have been scrutinized by critics in a discontinuous manner, usually with a monographic slant (an exhibition was devoted, for example, to the relationship between Gobetti and Casorati, and Governato also had his own monographic exhibition, although much remains to be discovered about his production, beginning precisely with that of the Futurists): the work of the artists who already in the early 1920s diverged from the artistic tendencies of the artists close to Fascism, or who even opposed a direct contestation to Fascism, and of which mention has been made here in brief and without any claim to exhaustiveness, has, however, never been considered according to a transversal and broadened point of view, and could therefore constitute a new, interesting field of research.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.