Abruptly extinguishing the yearning for freedom and the right to human and social dignity can sometimes have unimaginable repercussions, not always negative. Sometimes, in fact, abuse and deprivation can so shake the human soul that the eager search for redemption, when combined with a happy conjunction of events, is met with exceptional and unexpected results. The story of Mattia Preti (Taverna, 1613 - Valletta, 1699) is one such extraordinary case. All the more rare is his story, if we consider that, sacrifices and efforts made, even when paid dearly, usually do not guarantee a sure success. The decisive event, which changed the fortunes of the Preti family, and which for Mattia personally represented a clear recognition, occurred in 1661. In that year, "moved by zeal [the artist] offered to depict, and gild at his own expense the whole vault of our major conventual church of San Giovanni. "1 An episode this, which represented the sign of the regaining of a right erased for years. These are the facts as they unfolded. Let us turn the hourglass back to February 13, 1660.

The artist, by then a well-known figure in the artistic sphere, having received the title of Knight of Grace of the Order of Malta, which meant being able to “enjoy all the gratie, honori, and privilegij, which the other Cavaglieri d’obedienza magistrale enjoy, ”2 in a truly commendable gesture, offered the Order of St. John to decorate the vault of the present Co-Cathedral of Valletta, Malta. A “disproportionate” price, as highlighted by Giuseppe Valentino (founder and director of the Taverna Civic Museum), that “Mattia Preti paid to regain, in his name, the noble rehabilitation of the family, paid with very hard and incessant years of work on the island [of Malta] in which the artist nevertheless managed to reach the apex of his gigantic creative force. ”3 The antecedent, which constitutes the crux of the story, goes back about a decade before Mattia’s birth (in 1613), to 1605, when in Calabria, in Taverna, his hometown, with some “rules imposed by the ruling noble classes [...] through the implementation of a new form of state independence [one] erased in one fell swoop every principle of democratic equity to reintroduce involutive forms of feudal power. ”4 A certainly not insignificant episode, which not only conditioned, from that moment on, the fate of the Preti family, but which in Mattia originated a series of changes, moves and travels from Calabria (perhaps as early as 1624) that were motivated by the recovery of a sense of honor and likewise, were aimed at rehabilitating the dignity of his lineage.

|

| The vault of the Valletta Co-Cathedral, painted by Mattia Preti |

|

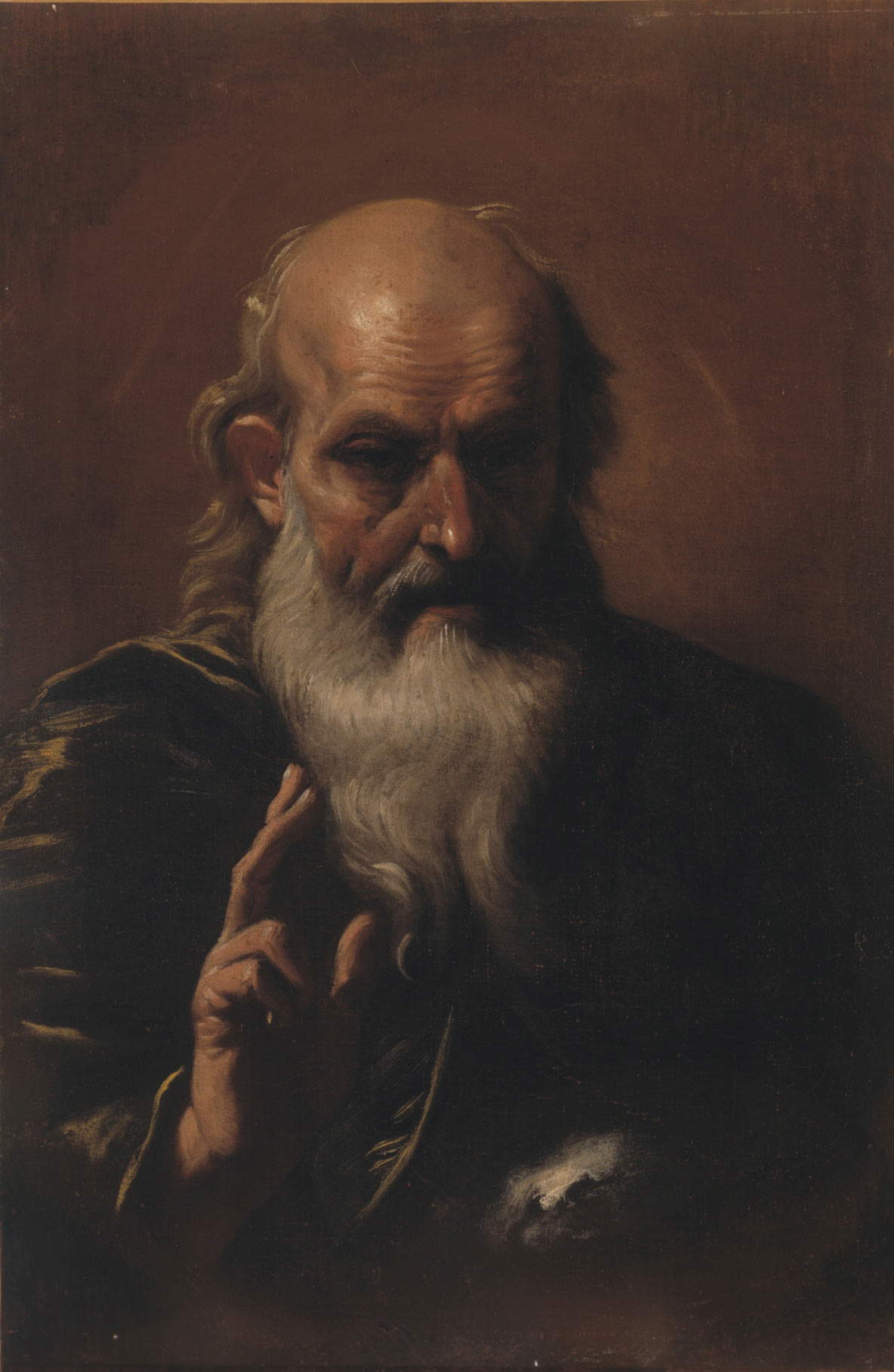

| Mattia Preti, Preaching of Saint John the Baptist with self-portrait (1672; oil on canvas, 290 x 202 cm; Taverna, San Domenico) |

After that gesture, there were numerous confirmations of one’s social prestige over time, all symptomatic of a real recognition of Mattia Preti in Calabria: proof of this, in 1672, is that form of “self-satisfaction” that is the self-portrait made within the canvas the Preaching of St. John the Baptist: the artist thus elevated his own pictorial dignity while also affirming his social dignity. And later, with the opportunity to build “his own aristocratic altar within the most important religious building of the place, ”5 Preti, in the same church of San Domenico, reconfigured the social framework of his family by restoring the dignity of his own surname. In Malta, too, in the decoration of the Co-cathedral, particularly in the works of the Baptism of Christ and St. John questioned by priests and Levites, Mattia Preti will pay homage to his hometown, clearly manifested in the effigy of Taverna as “a version of a real ’pictorial testament’ that the Cavalier Calabrese decided to leave to posterity, before his earthly end. ”6 But what sort of hometown are we talking about? What is the history of Taverna? And what had it been in those years to become, ultimately, the incunabulum of a great artist’s talent? While it cannot be said that Taverna for Mattia Preti was the place of artistic affirmation, as were the cities of Rome and Valletta, the Calabrian town nevertheless represented the point of origin for the formation of his talent, especially considering the presence of some fundamental social components and a lively ferment that has always characterized the town, albeit in different ways throughout the centuries of its long history.

Taverna has ancient origins. Its artistic heritage, represents “the legacy of a forgotten Greek origin made more reliable today by the findings in the archaeological excavations in Uriah, where the Greek colony of Trischene probably stood. ”7 But especially, since the medieval period, it has been a very fruitful productive center: an important silk production activity was active here (in fact, the relations between Venice and Albi, a neighboring municipality, are to be clarified), a documented paper production (there was a factory in the Village of St. Sophia), which could also confirm Preti’s habit of copying prints. "In the seventeenth century, the graphic patrimony [as evidenced by the publication of an inventory] must have reached considerable quantity and value, given that Cavalier Calabrese himself "solea copiare alcune stampe degli elementi del disegno lasciate in casa da Gregorio suo fratello allor ch’ei partì per Roma. "8 However, beyond the more pragmatic, productive, in a word, economic aspects, Taverna had also been a key junction in the establishment of temporal power. It should be remembered that as early as the fifteenth century the Church here had been lavish in its support of artistic commissions. Commissions that even at other times had been promoted by the Dominican order (active in Taverna since 1464 with the foundation of the monumental church of St. Dominic) and the Franciscans. The latter even managed “to channel sculptures by Antonello Gagini and his Sicilian workshop into their convents perched on the foothills of the Crotone Sila ”9. All this proves that “social history determines [sometimes] the history of the art of any place, whether small or large ”10, and likewise, confirms, how much cultural ’intermittencies’ can find space even in a small, seemingly marginal village, such as that of the Calabrian territory, where, in spite of an established preconception that always sees it among the most backward regions, a history, in the past, was written that was very lively: Taverna was a culturally vibrant, prolific center. This vibrancy was mainly due to the presence, as mentioned above, of religious orders and authorities, but we know that the large number of noble men of letters in the canonical and civil laws, too, is not an element that should remain extraneous in the indication of social renewal through the diffusion of new media such as prints (lithographs in particular) and specimens of illustrated volumes. It is well known how, although relations between Taverna and Naples or Rome were assiduous, “the making of some paintings [is] directly traceable to the diffusion of graphics. ”11

|

| View of Taverna. Ph. Credit Francesco Fratto |

|

| The church of San Domenico with the statue of Mattia Preti. Ph. Credit Franco Parrottino |

|

| Interior of the church of San Domenico. Ph. Credit I love Calabria |

|

| Mattia Preti, Christ Lightning - The Vision of St. Dominic (c. 1680; oil on canvas, 372 x 260 cm; Taverna, church of San Domenico) |

|

| Gregorio Preti and Mattia Preti, Madonna and Child in Glory between Saints Gennaro and Nicholas of Bari called Madonna of Purity (c. 1636-1644; oil on canvas, 248 x 196; Taverna, San Domenico) |

|

| Mattia Preti, God the Father Blessing (c. 1672; oil on canvas, 76 x 53 cm; Taverna, San Domenico) |

|

| Mattia Preti, Miracle of St. Francis of Paola (c. 1678; oil on canvas, 183 x 127 cm; Taverna, San Domenico) |

|

| Mattia Preti, Crucifixion (c. 1682-1684; oil on canvas, 233 x 159 cm; Taverna, San Domenico) |

|

| Mattia Preti, Madonna and Child between Saints Lawrence, Francis Xavier, Apollonia and Lucy known as Madonna of Carmel (1770s; oil on canvas, 206 x 136 cm; Taverna, San Domenico) |

|

| Mattia Preti, Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian (before 1687; oil on canvas, 272 x 195 cm; Taverna, San Domenico) |

|

| Mattia Preti, Martyrdom of Saint Peter of Verona (c. 1687; oil on canvas, 290 x 202 cm; Taverna, San Domenico) |

|

| Mattia Preti, The Madonna and Child Deliver the Rosary to Saints Dominic and Catherine of Siena (c. 1687-1689; oil on canvas, 285 x 230 cm; Taverna, San Domenico) |

|

| Mattia Preti, Infant Redeemer (c. 1690; oil on canvas, 185 x 112 cm; Taverna, San Domenico) |

Valuable evidence of Taverna’s artistic richness is also reported by a scholar who first played an important role in the recomposition of Preti’s story and opera omnia, Alfonso Frangipane (Catanzaro, 1881 - Reggio Calabria, 1970). “And in Taverna, more than in any other city of Calabria, seventeenth-century art was able to assert itself, rising to true splendor. ”12 After this hint of praise of the city, however, Frangipane goes on to make a harsh attack on its people, who were guilty of the degradation that raged in 1970, the year of the famous theft that will be mentioned in a moment, because he reports: “they have never understood and loved our art (and he ascribes to them the blame for the lost splendor of primitive beauty because if the churches of Taverna were devastated by the theft of some works) to this blind fury the conscience of our people has [never] rebelled. ” 13 Taverna thus, seems to have two souls, that of a beauty that originated here thanks not only to Mattia Preti, and the more ephemeral one, connoted by a loss of beauty, a treasure that it has not always been able to preserve.

The episode of the theft that took place on the night of February 25-26, 1970, is experienced even by the very young Giuseppe Valentino himself, who with all reasonableness may have developed from that precise moment an interest in Preti’s work and a perhaps unconscious need to return to his city part of a heritage of inestimable artistic and other value. On that night eight paintings by Mattia Preti, the MadonnadellaProvvidenza by his brother Gregorio and two works by unknown 17th-century authors were stolen from the altars of the church of San Domenico. Of this “usurpation,” which represents a dramatic event, even though the works were found two years later, between 1972 and 1973, traces still remain in some of the spaces set aside for the cymatiums that remain empty to this day. But those same “voids,” mute witnesses to an identity theft, are there to tell us much more about what the church of San Domenico can tell us. Sometimes, the marks of damage to beauty vilely done remain for a long time or forever, never to be repaired. Even these traces then, seemingly less obvious and less important of an intangible heritage of memory and identity are just as indicative to speak of a place, a city, a community. What is still surprising is that here, compared to other Italian places, not all of them be it well understood, the “rebellion” is soon stifled, the loss of works of art does not arouse, except for a short time and in a few, a feeling of bewilderment that produces a will to redemption. Mattia Preti, who sacrificed many years of his existence to recompose the prestige taken from his family, and the legitimate rights he was entitled to enjoy, would still have much to teach.

|

| Altar of the church of San Domenico in Taverna where the missing painting of the Holy Family was located |

|

| The missing cymatium |

1 G. Valentino, Configurations of a social redemption. Diaspora in Taverna’s self-portrait, p. 35.

2 G. Leone and G. Valentino (eds.) Caravaggio and Mattia Preti in Taverna: a possible comparison. Gangemi, Rome, 2015, p.53. Catalog of the exhibition of the same name held at the Taverna Civic Museum from March 25 to May 3, 2015.

3 Id. p. 35.

4 Id. p. 32.

5 Id. p. 38.

6 G. Leone and G. Valentino (eds.), Gangemi, 2015, p. 49.

7 G. Valentino (ed.), Art in Mattia Preti’s Hometown. From the saved heritage to the new collections of the Taverna Civic Museum, edited by Museo Civico di Taverna edizioni, printed by Industria Grafica Rubbettino, Soveria Mannelli, 2010, p.9.

8 M. Puleo,The graphic treasure. Inventory of prints in the homeland of Mattia Preti, cittacalabriaedizioni, Rubbettino group, Soveria Mannelli, 2006, p.14.

9 Id. p.11.

10 Id. p. 13.

11 Id. p. 14.

12 G. Valentino (ed.), Soveria Mannelli, 2010, p.9.

13 Id. p. 10.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.