The world has not been the same since Rothko

The article you are about to read was written by Emma RodrÃguez, a Spanish cultural journalist and contributor to newspapers such as El Mundo, El PaÃs, Turia and others, as well as the editor of “Lecturas Sumergidas,” an online magazine from which this article is taken. You can read the original at this link. The translation from Spanish to Italian is by Ilaria Baratta.

It all began one morning a few years ago now during a vacation in London. On a visit to the Tate Gallery, my steps led me to a room where I would stay for quite some time. In Rothko’s room, in front of that multitude of colors typical of the painter, in front of those accesses to the landscapes of the soul, to the mysterious voids, abysses of being, I understood that what was really essential was there, outside the hustle and bustle, the news and the habits, that in that place it was possible to stop everything and begin again, with other rhythms, with eyes and mind open to catch these little flashes of truth that go unnoticed when we are in a hurry, when we follow like automatons the evolution of the world and stop asking questions and listening to ourselves. I see myself sitting in front of the paintings, alone, distraught inside, wishing to stop time, searching for the proper language to express this set of emotion and strength in front of those expansive plains of ochre, brown, reddish, gray, violet, in front of those shaded doors or columns of a temple through which I entered without pre-existing codes, finding, amazed, the keys to access a closeness, a kind of lucidity, a happiness that I now find again when I review the pages of a biography that is about to be published in Spain by the PaÃdos publishing house and that I hastened to read, moved by a yearning to know more about the man who, from that moment on, became one of my favorite painters.

|

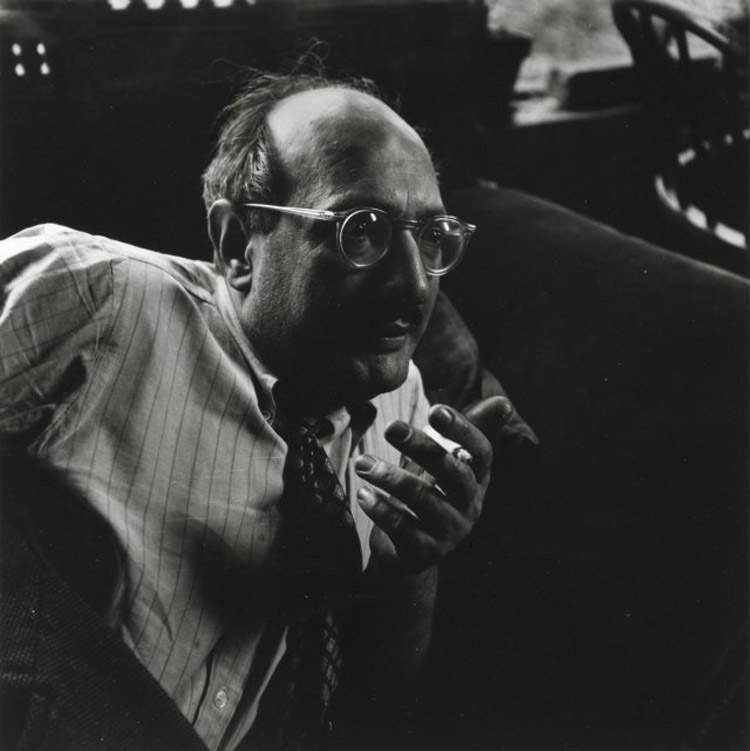

| Mark Rothko photographed by Consuelo Kanaga in 1949 |

|

| Rothko’s room at the Tate in London |

French lecturer and historian Annie Cohen-Solal is the author of Mark Rothko. Buscando la luz de la capilla, an excursus on the life and times of an artist whose value lies not in the high quotations he achieved and continues to achieve for his art, but rather in his ability to amaze us and lead us to a non-reality that affects us. Thanks to the biographer, we have access to the lights and shadows of this man, born in Daugavpils, Latvia, in 1903, who decided to end his life in New York, in 1970, when his name was already one of the greatest in contemporary art.

The artist never stopped searching, never stopped evolving, never stopped believing in art as a language of the sublime, as a tool to penetrate the deepest layers of things. In one of his texts, Space in painting, included in his book Writings on Art, to which I will also refer in this article, the author reflects on the intensity of feeling, the depth of emotion.

When we talk about access to knowledge we are talking about an unveiling; the latter expression implying a stripping away of all veils, a lifting of the depths to different knowledge, or a shifting of the veils that obscure what lies behind them tells us. He adds: There is room in expression to make the obscure clear or, metaphysically, to make the remote close in order to draw it toward the order of my human and intimate intellect (...) This is what my world is composed of: a little bit of sky, a little bit of earth and a little bit of movement....

|

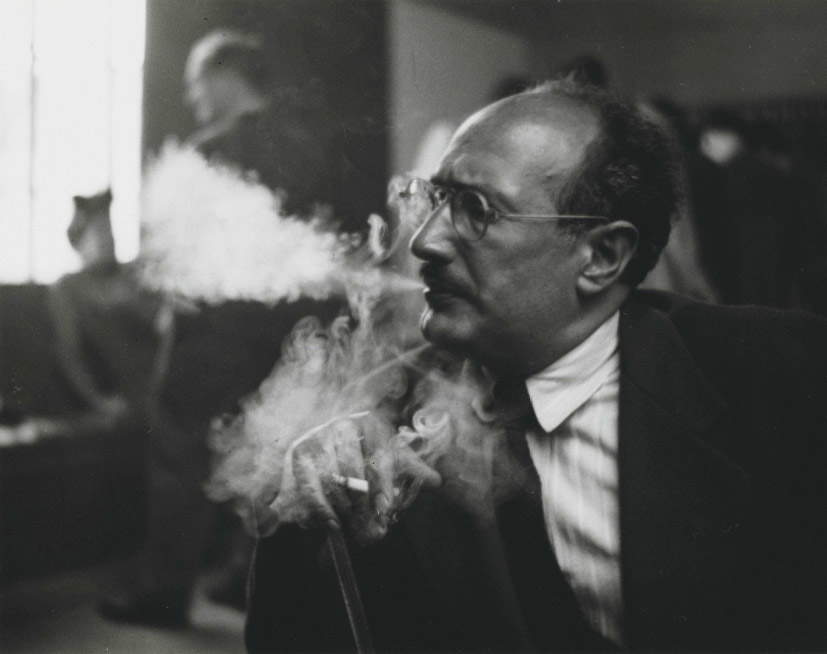

| Mark Rothko photographed by William Heick (1949-1950) |

It seems to me beautiful this argument, which, in a way, reveals in a philosophical key what fascinates us so much about Rothko’s painting: its capacity for unveiling, its access to inaccessible regions, this mystical, spiritual plane, which he did not come to fully recognize, despite the fact that he knew that his works should be appreciated as a whole, in a kind of harmonious dance, in intimate, cozy spaces, suitable for meditation, for calm. That total feeling of serenity imbues the spirit of the visitor to the Tate in London and to the other places dedicated to the painter: to the National Gallery in Washington, to the Houston Chapel or to the Rothko Center in Daugavpils, Latvia, the ancient locality of Dvinsk, where he was born.

As I contemplated and was captivated, that distant day, by Rothko’s expanses, I thought I was calm, balanced, that I must be infected by the miraculous effects of color, but never further from reality. Cohen-Solal’s biography portrays a tormented, contradictory being, constantly struggling between his conception of the purity of art and his desire to achieve success, which was not possible without entering the market game. When I was young, art was something solitary: there were no galleries, no collectors, no critics, no money. In spite of that it was a golden age, there was nothing to lose but a goal to be achieved... declared the artist in 1960, when he was far, far away, from that initial situation; when museums and art galleries were already contending for him, when the passage of time had led him to idealize an era in which, despite that authenticity and freedom he remembered so much, it made him worried that his work was not rightly recognized and valued.

Committed, with a strong social conscience, always on the side of the underprivileged, the excluded, a circumstance he experienced on his own skin, as the son of Jewish emigrants who, at the beginning of the twentieth century, fled the old Russian empire with the fear of persecution and pogroms (the first chapters devoted to the artist’s childhood, to the origins of his family, are very interesting); for him integration was always a difficulty. From the reflexive, critical, combative attitude, it was not easy for him to accept the rules of the university of the time, nor to accept the rules of art, its commercial aspect, a circumstance to which one must add the incomprehension of his era, the attacks, at first fierce, towards a work of rupture, capable of communicating with unknown codes, equal to the great visionary artists, pioneers, who face reticence in exchange for officialdom.

|

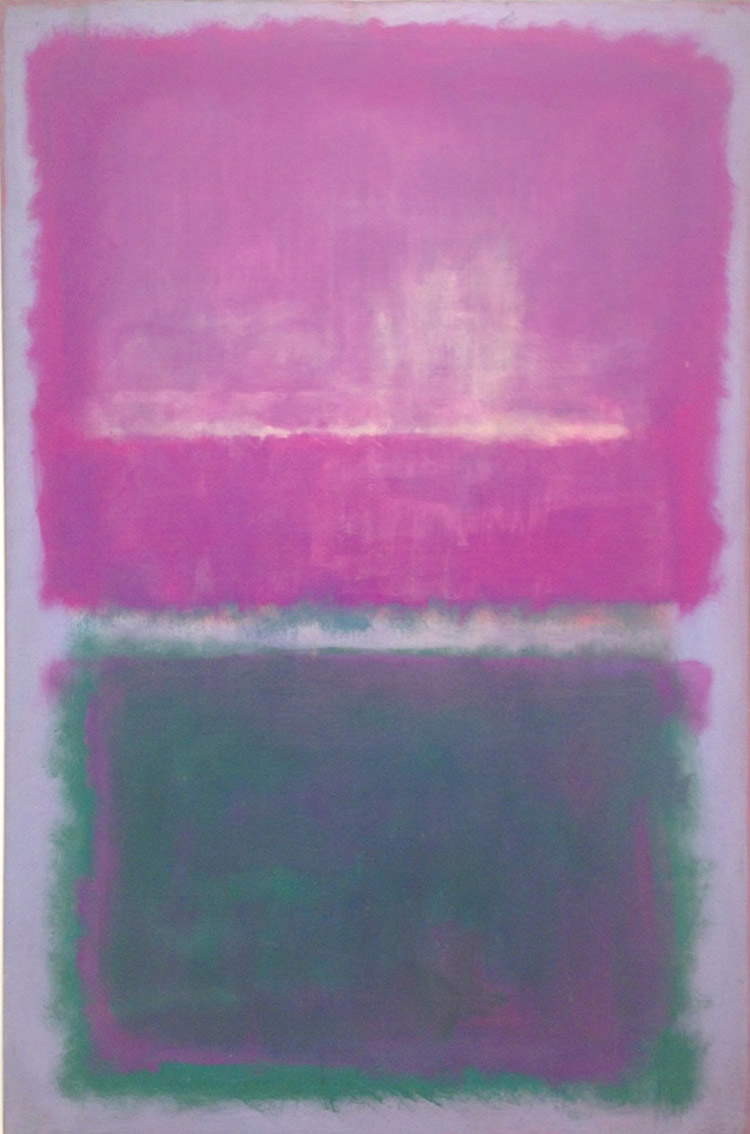

| Mark Rothko, Untitled, Lavender and Green (1952; oil on canvas, 171.7 x 113 cm; Private Collection) |

The portrait of this artist in perpetual crisis, struggling between his convictions and his achievements, amidst overwhelming and intricate commercial maneuverings, as his art grew and rose to planes that were never material, far from the tangible, from the real: it is one of the great purposes of a clarifying dedication. There is a fact in Rothko’s life that says a great deal about the struggle with himself and his environment, about the turmoil it caused him to enter the networks of capitalism. In the biography, one chapter analyzes what happened when he was commissioned to do a series of paintings to decorate the luxurious Four Seasons restaurant, part of a massive, 34-story skyscraper project, home of the Seagram Company, at 375 Park Avenue, a symbol of New York’s wealth, a symbol of U.S. success.

A sales order, reaching the astronomical sum of $35,000, with a $7,000 down payment for decorating the building, sealed the deal. In addition to Rothko’s contribution, works by Picasso, Miró, Stuart Davis and sculptor Richard Lippold were counted on. Our protagonist set to work, but he didn’t feel he fit in, couldn’t find the right way, and tried to figure out what was bothering him so much.

In 1959, on a transatlantic voyage he arrived in Europe, together with his wife and eight-year-old daughter. Mark Rothko became friends with writer John Fischer, with whom he was able to vent freely. Eleven years later, after the painter’s suicide, Fischer, who had carefully transcribed Rothko’s words, aware that he was witnessing an important episode in the life of an already famous artist, recounted Rothko’s confidences to him at a bar counter in an article published in Harper’s magazine. Cohen-Solal mentions it, but we find it whole in Miguel López-Remiro’s edition of Writings on Art (Paidós Estética). It is an absolutely significant account because it reflects that agitation the painter felt at seeing himself inclined to betray his principles. Rothko, according to the author’s account, told him that they had commissioned him to make a series of large canvases to cover the walls of the most exclusive room of a very expensive restaurant in the Seagram Building.

A place where the richest bastards in New York go to eat and brag told him. And he assured him that he would never accept such an assignment, that he had accepted it as a challenge, with the worst intention, with the hope of making something that would ruin the appetites of all the sons of bitches who would be eating in the room, adding that to achieve this oppressive effect he wanted, he was using dark tones, darker than anything he had done before.

The story ended abruptly: the paintings were never hung in the dining room, however, the time invested in the project was a time of research, discovery, and challenge, as Annie Cohen-Solal notes in her essay. After all, the path of research had led Rothko to emulate, in his own way, the claustrophobic effect that Michelangelo had achieved on the walls of the Medicean Library’s staircase room. He had achieved, he told Fischer, exactly the kind of feeling I am looking for: to make viewers feel that they are trapped in a room in which all the doors and windows are bricked up, so that the only thing they can do is to be face to face with the wall.

By depicting the artist as a demiurge, creating an enclosed cell for the viewer, inspired by Michelangelo, Rothko was trying to achieve neither more nor less than a drastically new form of dialogue with the audience, the biographer points out, because that tortured decision, that series that plays with color and vertical lines like columns, pillars of windows to the void, presupposes a source of maturity for the artist, and ended up finding, in the end, a more suitable place to be placed (of the initial seven canvases conceived for the restaurant, the series became about thirty and ended up in several centers, including the Tate Gallery room, a place appropriate to the idea of ensemble, of narrative, of atmosphere conducive to emotion).

I hate and suspect all art historians, experts and critics. They are a gang of parasites who feed off art. Their work is not only useless but also misleading. They say nothing worth listening to either about the art or the artist, except gossip, which I agree can get to be interesting he told John Fischer on another occasion, manifesting a moment of rebellion in his own path, in a certain precise way, since not a few times he felt adulated by positive comments about his work and close to specialists and heads of art institutions.

|

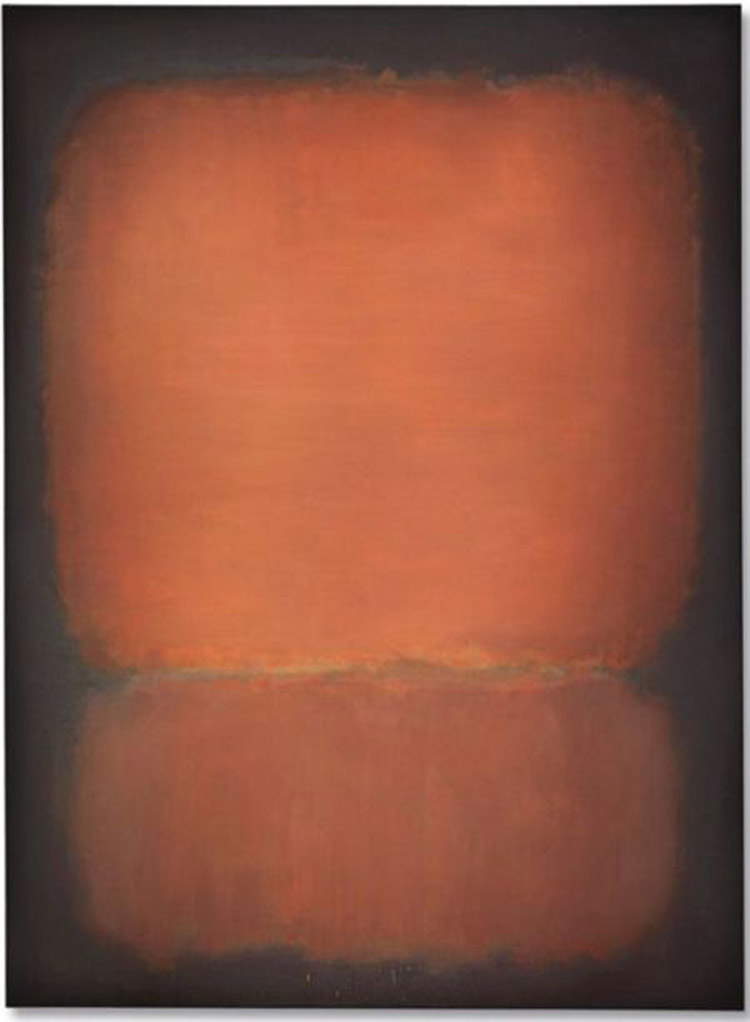

| Mark Rothko, No. 10 (1958; oil on canvas, 239.4 x 175.9 cm; Private Collection) |

Contradictory, complicated, perfectionist, stubborn, insecure, earthly and spiritual at the same time, the artist always experimented, carried on, longed to reach those points of perception, of enlightenment that lay beyond what can be understood. This is how he shows himself in the biography that I comment on here, a narrative that is exciting for all that it brings about the artist and his evolution in solitude, with his own research, but also in the company of his fellow adventurers, the painters of a movement, Abstract Expressionism, capable of shaking the conventional and conservative pillars of North American art and propagating itself beyond geographical frontiers.

The biographer invites us to enter the artist’s studio and follow his steps, from childhood to his last days, when his health began to fail, when he was unable to cope with depression and dissatisfied, despite having achieved the recognition for which he worked so hard, he ended his life in February 1970, at the age of 67. Thanks to him we go through all the stages of his journey (the figurative beginnings, the approach to mythology, the transition to the abstract). We see him as a child studying Talmud, a discipline that marked his character; in his early failures as a student, when he did not settle in a rigid university; in his evolutions and transformations, in his agreements and aversions, in his frustrations and successes. And at the same time we witness the fascinating era in which he lived, for the painter was a key player in the boom of New York as an art capital, opening the door to a refreshing, renewing artistic language.

There is a memorable photograph taken in 1950 by Nina Leen for Life magazine in which the painter appears in the front row, surrounded by fellow adventurers such as Jackson Pollock, Clyfford Still, Robert Motherwell, Willem de Kooning, Walker Tomlin, Ad Reinhardt and Hedda Sterne, the only woman in the group by the way. A total of fifteen rebellious artists came to be known as the irascibles, beginning with a letter of protest sent to the director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and published in the New York Times, in which they criticized the aversion to emerging art by an institution that had no qualms about rejecting the spectacular collection of works by new contemporary U.S. artists offered by patron Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, later founder of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

|

| The irascible group (photo by Nina Leen, 1951). Starting from the bottom, left to right: Theodoros Stamos, Jimmy Ernst, Barnett Newman, James Brooks, Mark Rothko, Richard Pousette-Dart, William Baziotes, Jackson Pollock, Clyfford Still, Rotert Motherwell, Bradley Walker Tomlin, Willem de Kooning, Adolph Gottlied, Ad Reinhardt, Hedda Sterne. |

These irascible artists had yet to know that soon some of them would become highly esteemed figures, appreciated, by dedicated critics, sought after by major museums. The first among them was Pollock, followed soon after by Rothko. He, who had always complained about his financial difficulties, realized in the late 1950s how his sales were increasing and how his paintings were beginning to be priced at figures close to $5,000. This sudden economic availability gave him a new burden to worry about tells Annie Cohen-Solal.

It was a great cause of problems for the artist. Read Mark Rothko. Buscando la luz de la capilla is to witness, I insist, the conflict the artist felt between art as a tool of engagement, of rebellion, of spirituality, and its inevitable commercial component. As he achieved more success, he too felt threatened by the evils he had previously manifested. The conflict left him disheartened, insecure and wracked with guilt declared Katherine Kuh, superintendent of the Art Institute of Chicago, a professional who enjoyed the friendship and respect of an artist whose value, in every sense, did not cease to grow after his death.

In the 2000s, the price of Rothko’s works skyrocketed in auction houses, long exceeding the figures demanded for his contemporaries such as Pollock, De Kooning, Newman and Still, with eye-popping figures around $80 million writes the author of a book that contains such difficult chapters as that of the deception and exploitation of those who managed the artist’s works in the Marlborough gallery, but also others that are absolutely clear where we sense the artist’s excited satisfaction before the realization of what would be his dream, an aconfessional chapel in Houston, built by Jean and Dominique de Menil, two immigrants like Rothko, upper class but strangely with radical leftist ideas, who came to the United States to escape Nazi-occupied France. Both followed the directions of the artist who, at last, had found the desired position that conformed to the mystical, sacred sense we perceive in his large canvases, although, as writer John Fischer says, only once did I hear him imply that his work expressed a religious impulse, deeply hidden.

|

| Rothko Chapel in Houston |

As he worked on the chapel, which was to become the greatest undertaking of his life, his colors grew darker each time, as if he was taking us to the threshold of transcendence, to the mystery of the universe, to the tragic mystery of our perishing condition reported Dominique de Menil in 1972. Critic Robert Rosenblum refers to the abstract sublime in Rothko in this way: Like the mystical trinity of sky, water, and earth that, in Friedrich and Turner, seems to emanate from a hidden source, the floating horizontal layers of veiled light in Rothko seem to conceal a total and remote presence that we can only sense and never fully apprehend. These infinite, brilliant voids lead us beyond reason, to the Sublime. We are left only to surrender to its radiant depths.

The Houston chapel, a minimalist octagonal construction by architects Howard Barnstone and Eugene Aubry, who started from an earlier design by Philip Johnson, brings together much of the research and achievements of Mark Rothko, who wanted to offer the public, as Annie Cohen-Solal puts it, not just a painting but a whole environment; not just a visit, but an authentic experience, not a fleeting moment, but a genuine revelation. His originality was rooted, according to Motherwell, in his concept of representation. He was interested in effect, and the technique was to provoke a specific effect declared his colleague and fellow adventurer. By allowing the viewer to enter his work, Rothko initiated a sophisticated analysis by altering his means and using elaborate methods, almost alchemy, that would not be understood until long after his death, we return to the words of the biographer, who goes on to refer to the artist’s reserve in revealing his techniques and experiments, something those who knew and frequented him noted firsthand.

The Rothko Chapel was opened in 1971. The building is reflected in a pond, from which rises an irregular obelisk, the work of Barnett Newman. A year later the painter took his own life, perhaps aware that his work had already reached the heights he wanted to reach. He had thrown a big party in his studio in 1969, which in retrospect can be interpreted as a farewell. There has been much speculation about the reasons for the suicide, but again the words of John Fischer turn out to be very revealing: Rothko, as I understand it, felt very much that he was obliged to provide matter, whether it was for the del trust that succumbed to the investments, or for the aesthetic exercise. I have been told several versions of why he committed suicide: that he was ill, that he had not been able to produce anything in the last six months, that he felt rejected by an art world that had diverted its inconstant gaze to younger, worse quality painters. Perhaps, among these, something is true, I do not know. I suspect that at least one of the contributing causes was that continuing wrath ( ), the justified wrath of a man who felt he was destined to decorate temples but had to be content with his canvases being treated as commodities.

I cannot end this article without mentioning the epilogue to Cohen-Solal’s biography, dedicated to the Mark Rothko Art Center in Daugavpils, Latvia, his homeland, a profound loss for the artist, who was forced to leave his childhood lands. In 2013, when it was inaugurated, his daughter Kate uttered the following moving words, collected as the introduction to this chapter.

When I was little, my father would come and sit next to me and we would look at a map together. He would show me this territory [between Latvia, Lithuania and Poland] and he would say, You can’t see it now because they have changed the borders and they are completely different from the borders of my time, but this is where I was born.

Simple and beautiful remembrance, as simple and beautiful is the word emotion, mentioned many times in Rothko’s writings: the emotion he wished to convey through his art, to the point of tears; the emotion he found in children’s drawings, which interested him greatly during his long career as a teacher. I do not want to end this article without letting the artist himself speak. I choose one of his texts, one of the simplest, included in his Writings on art, a work that gives an idea of its theoretical, reflective character, its philosophical aspect. It is a transcript of a lecture he gave at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn.

|

| Mark Rothko, No. 17 (1957; oil on canvas, 232.5 x 176.5 cm; private collection) |

I would like to talk about painting a picture. I have never thought that painting a picture has anything to do with self-expression. It is about a communication about the world directed to another human being. When this communication is convincing, the world is transformed. The world never became the same again after Picasso and Miró. Their worldview transformed ours.... We pause when he says: People ask me if I am a Zen Buddhist. I am not. I am not interested in any other culture than our own. The problem with art is rooted solely in concretely fixing the human values of this culture. And later, when asked by someone in the audience about his large paintings, he replies, I try to create a state of intimacy, an immediate transaction. The big paintings put you inside them. Scale is something fundamental to me....

All this brings me back to the Tate Gallery room, to that unforgettable day, fixed in memory, when, really, I was able to get inside Rothko’s backgrounds and believed I was finding new meaning to things behind his open windows. The world did not become the same again after Rothko, I keep thinking.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.