The world before the world. Egyptian cosmogony and the Heliopolitan Ennead.

In the thoughts ofearly man there was a connection between what was part of the nature around him and what he considered supernatural. The advent ofart played a fundamental role in the psychology of Prehistoric man as it was considered the first means of materializing magical ritual. The painting of a bull on a cave wall, for example, assumed occult powers that were able to transform the sacred representation into a concrete image. By thus stopping the animal on the rock, the primitive hunter had the impression that he had succeeded in capturing it even before the hunt. The thought of supernatural benevolence toward humans is thus the fundamental theme of all artistic practice developed during Prehistory. Through the thought of divine power, the first approach to a religion with rudimentary features and the unceasing thirst for curiosity, primitive man gave birth to myth: the only explanation devoid of philosophical and scientific thought capable of explaining the mysteries of existence. Its function is therefore to explain, pass on and provide a complete view of the ancient world and its historical, religious and natural beliefs. Myth was thus born with the intention of interpreting and providing an elucidation to each and every event.

Only with the rise of Greek civilization is the discipline of philosophy described as a system of intellectual principles developed according to investigative rules. The fundamental distinction between Greek character philosophy understood as scientific philosophy and philosophy in the sense of human thought is therefore given by its development in the various pre-Hellenic civilizations. Before Greece, Near Eastern peoples attempted to communicate abstract concepts by understanding philosophy as a religion, and not as a subject to be studied. Pre-Hellenic philosophical thought is based on the experimentation of the individual and the subjectivity of reality, not on objectivity fixed by a rulebook that can be studied. In this case, the Egyptian civilization impressively highlights and connects the relationship between mythology, religion and philosophy as the whole system of human thoughts. In an ancient landscape of cosmogonic and theological mythologies, Egyptian philosophical thought with its initial creation myth attempts to explain the birth of the universe through a concept that is more familiar and easy to understand than the principles of Greek philosophy. Thus, for Egyptian mythology, the visual and communicative content of living beings taking part in the composition of the individual pieces of the universe as distinct individuals and with their own personalities becomes fundamental. Substantial difference with Christian mythology for example, which sees the universe formed by individual physical components created by a single deity and not by the composition of living beings.

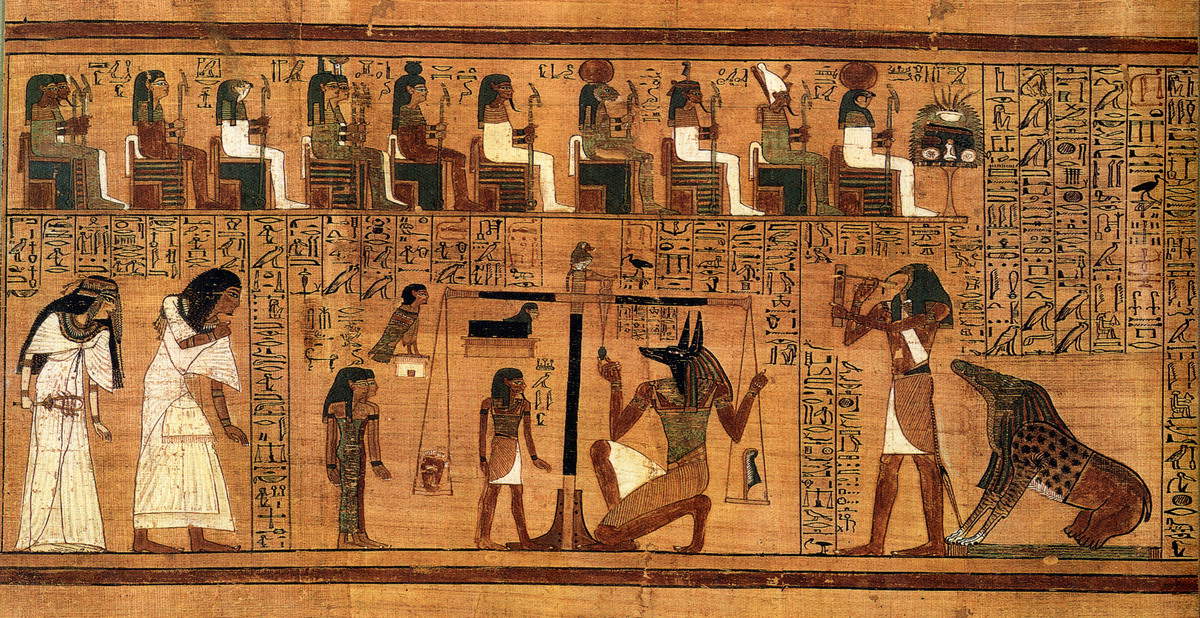

For ancient Egypt, the set of beings who governed the forces of the universe took the name Ennead, which from the Greek ἐνννεάς-άδος and later from the Latin enneas-ădis literally means nine. Tracing the Egyptian cosmogony and the distinct living individuals that make up its universe, the term Ennead can therefore be translated into group of the nine or group of the nine gods. The city of Iunu or Onu “pillar city” later transmuted from Greek to Heliopolis, in Lower Egypt on the eastern bank of the Nile, represents the first focus of cosmogonic veneration toward what is known as the great Heliopolitan Ennead. Beginning with the progress of the culture that developed in the Nile delta areas with the annual phenomena of flooding and drying up, it entrusts the deity Nun therefore with the ancestral concept of the world before the world. Regarded as an early form of literature, the Ennead narrative sees its birth around 2500-2000 BCE. During the end of the Old Kingdom (2700-2192 B.C.) and the beginning of the First Intermediate Kingdom (2192-2055 B.C.) the walls of burial chambers and corridors of pyramids, such as the Pyramid of Thetis, were engraved with rituals, inscriptions and magical-religious formulas in the form of hieroglyphics. These are named the Pyramid Texts and still represent the oldest body of Egyptian religious scriptures. The texts contain different types of incantations that arose for the purpose of protecting the pharaoh on his journey to the afterlife in order to enable him to ascend well among the gods.

Although the pyramid texts were read and chanted only by the priests, who had access to the burial chambers, the entire mortuary room can be considered an early exhibition space of an artistic and historical nature. An object of any nature placed in the space succeeds in framing the space itself. In this case, an Egyptian burial chamber takes on a double significance: it represents the space that displays within it the object-work (the texts), and it becomes the work itself by being part of the huge complex (the pyramid). Pyramids, understood as an initial exhibition space, do not take on the same atmosphere that can be provided by the white, aseptic walls of a particular contemporary art gallery or museum. The history of modern art, closely linked to the concept of space-cell, therefore conflicts with the conception of space in antiquity: if in the former case the gallery or museum is functional as a support for the works, in the latter it merges with the object presented within it, becoming a single artistic organ. Therefore, pyramid texts become important as they communicatively and textually represent Egyptian cosmogonic mythology, are a work of art, serve as archaeological evidence, and are a source of study. According to cosmogony, Heliopolis stood at the place where in a remote time the primordial hill named Tatenen “emerged land” from the chaos of the dark and primitive waters of Nun. In 1841 Ivan Ajvazovsky, (Feodosiya, 1817 - 1900) a Russian painter associated with the Romanticist current, would deal with the theme through the painting Chaos (Creation). Even before the creation of the universe and its components, the interest of Heliopolitan cosmogony fell on the enigmatic figure of Nun: the first original element, the primordial entity not of divine nature, a dark, liquid mass that had no beginning and will never have an end. A watery expanse that covered everything from the beginning of time, as described in the Pyramid Texts (Expression 571):

1466c. before the heavens existed, before the earth existed,

1466d. before men were born, before gods were born, before death was born.

According to myth, the emergence of the first earth from the waters generated the Benben, a sacred pyramid-shaped stone also regarded as the primordial pyramid on which Atum, the father of the gods, resided. The Benben, also known as Pyramidion, has a close connection with sexuality and the sexual act; in fact, from the act of autoeroticism practiced by Atum were generated the deities that make up the Egyptian pantheon.

Expression 527:

1248a. To say: Atum created by his masturbation in Heliopolis.

1248b. He put the phallus in his fist,

1248c. to excite desire in such a way.

1248d. The twins Shu and Tefnut were born.

The genesis of the Heliopolitan universe thus began with the creation of the first divine couple: Shu, primordial personification of air, and Tefnut the moisture; sister and bride of the latter. From the first couple, Geb, the earth, and Nut, the sky were then begotten while in turn from the two brothers were born Osiris, Isis, Seth and Nephthys. Here, then, is the group of nine. The rules governing the world of artistic representation are based on the idea of balance and from the symbolism of shapes and colors. The figure of a deity engraved on a wall possessed its own identity through distinct characteristics that never embodied the subject in a form of human reality, like the Greek deities of the fifth century. Egyptian art is symbolic, represented rather in a primitive form that allows for the most simplified reading. Painting a god larger than another figure symbolically represents his greatness. To depict his body in a specific color is to assign a well-defined symbolism to the figure; in the case of the depiction of the primordial waters Nun, the body of the deity is shown painted blue, the color of water, as is that of Tatenen the primordial hill born from the darkness of its waters.

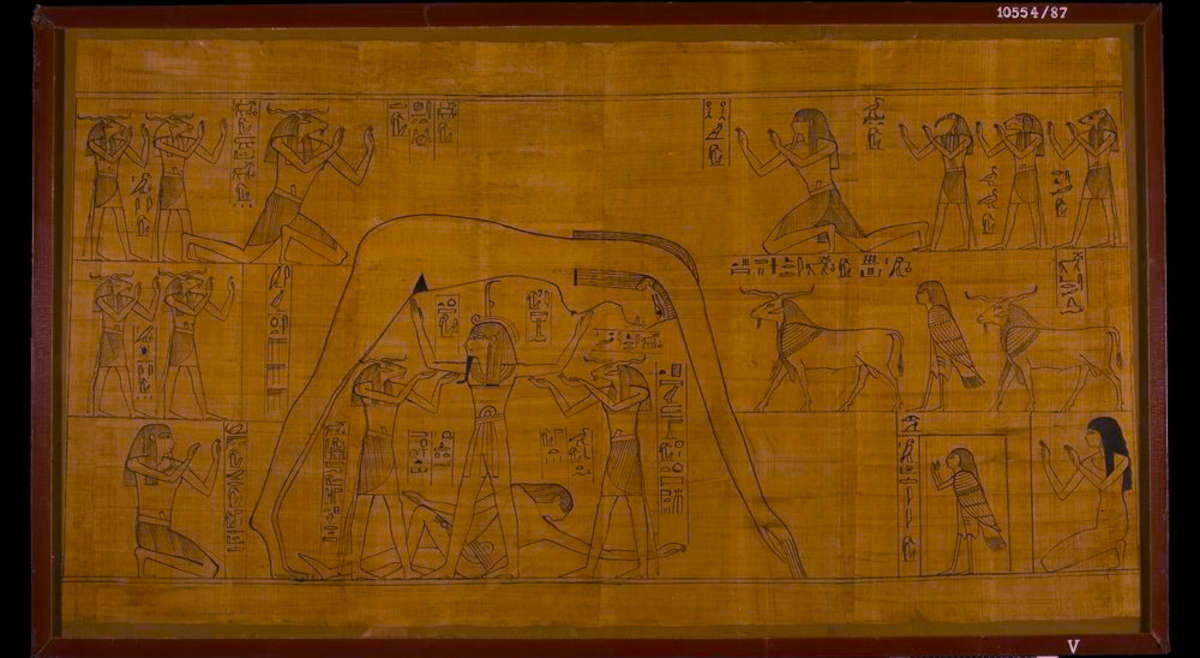

Skin color, detailed symbology or even zoomorphic features of a deity allowed and still allow for the recognition of the analyzed figure. Staying with the Heliopolitan cosmogony, among the most interesting images is surely that of the goddess Nut, the heavenly vault. In her most recognizable figure, the goddess in fact is arched and stretched above Shu and Geb, her body is covered stars and painted blue. In contrast to Greek mythology, where the figure of a suffering Atlas holds up the sky and the weight of the world, Nut who represents of the Milky Way, bent over the earth does not hold up the sky with suffering, for she herself is the sky. Her figure in this way takes on a strong symbolic meaning not only for cosmogony but also for cosmology, which has always been dear to the people of Egypt. However, the primitive Egyptian symbolism begins to falter with the course of the millennia. The developments of the various civilizations vying for the Mediterranean basin bring Egypt’s artistic landscape to a sharp crisis heading toward an end with the founding of Hellenic culture. The entry on the scene of the Greek and Roman peoples thus begins the twilight of the Egyptian gods, their symbolism, and especially the exhibition spaces moving toward a new phase of space and art.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.