“There are undoubted consonances between the mosaic decorations of the Adriatic city and the dazzling visions of the sacred poem: light and colors play a primary role in both cases as the expressive means necessary to represent the indescribable, giving body to incorporeal images and infusing fictitious movement to what is ultimately motionless and eternal.” to hypothesize in these terms the links between the ancient art treasures of Ravenna and the images of Dante Alighieri ’s Paradise (Florence, 1265 - Ravenna, 1321) is scholar Laura Pasquini, author in 2008 of a dense essay on Dante’s iconographies with particular reference to Ravenna. The city lying on the shores of the Adriatic, as is well known, was the Supreme Poet’s last port of call: here Dante died in 1321, having probably arrived in 1319, although the date of his transfer from Cangrande della Scala’s Verona is not known with certainty. The choice of a small and then marginal city like Ravenna was, notes Massimo Medica, curator of the fine exhibition Dante and the Arts at the Time of Exile (Ravenna, Church of San Romualdo, from May 8 to July 4, 2021), is motivated by several factors. First, the political one: Ravenna was ruled by the Da Polenta, a family of the Guelph faith. Then there were purely practical reasons: the lord of Ravenna, Guido Novello da Polenta (Ravenna, c. 1275 - Bologna, 1333), had guaranteed safety to Dante and his family, especially since the city was experiencing a moment of great tranquility at the time.

Probably, there were also cultural reasons: the great scholar Marco Santagata explained, in his recent Dante. Novel, that Ravenna lacked a real court, and the city’s government was rather exercised by a kind of “family” towards which feudal-like bonds of loyalty were “ambiguously mixed with relationships of paid dependence,” but which nevertheless recognized cultural and artistic merits more than elsewhere. “From this point of view,” Santagata explains, “it anticipates to a small extent what will happen in the real courts, which will consider the presence of literati and intellectuals a value in itself (and therefore also a reason for economic investment.” This may also perhaps be the reason why Guido Novello is never mentioned in Paradiso (in Ravenna, Dante would write the last thirteen cantos of the Divine Comedy): a detail “significant of the fact that the relationship with that lord,” we read again in Santagata, “was on a level that could disregard both the blatant courtier encomiums lavished on Cangrande and the more elegant attestations of gratitude issued to the Malaspina.” Boccaccio even went so far as to assert that it was Guido Novello himself who had called Dante to Ravenna, in a gesture proper to a Renaissance gentleman patron, thus rather far from the mentality of the time: in reality, we do not know precisely how the approach occurred.

What is certain is that Dante did not remain insensitive to Ravenna art: this is what the exhibition in the church of San Romualdo tries to illustrate. The Ravenna in which the poet moved was certainly very different from the city that had been the capital of the Exarchate of Italy: nevertheless, Dante could still walk through the great monuments of Byzantine Ravenna, observing their magnificent decorations, the works of art that enriched them, and perhaps even admiring the works of contemporary artists that the newer churches preserved. In his recent L’Italia di Dante, Italianist Giulio Ferroni, quoting Canto VI of Paradise, the one in which the poet meets the emperor Justinian (“Cesare fui e son Iustiniano / che, per voler del primo amor ch’i’ sento, / d’entro le leggi trassi il troppo e ’l vano”), imagines precisely a Dante who, “certainly authoritatively accompanied,” enters the basilica of San Vitale on several occasions, "moving between the mighty vaults and contemplating the mosaics, illuminated as now by natural light, thinking of Canto VI of his Paradise, perhaps then already written or perhaps right here conceived, in front of the procession of the emperor, who, on the left side wall of the presbytery, seems as if staring at the beholder, from an unlimited unfathomable distance, from his golden silence sunk in the beyond.“ The figure of Justinian was also present in the mosaics of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo: for Dante, Justinian represented ”the legitimate empire,“ and that close link between temporal power and religious power that emerges from the Ravenna mosaics also echoes in Dante, for whom the concept of agreement between Church and Empire was dear: an idea for which the artist could find solace, Medica explains, referring in turn to Pasquini’s studies, ”also in other city mosaics such as the lost one in the apse of the church of San Giovanni Evangelista, where we know Arcadius and Theodosius II with their respective wives were depicted, along with the clipeate images of Constantine the Great and the emperors of the Valentinian-Theodosian dynasty symbolically associated with the depiction of the enthroned Savior, placed in the center of the apsidal basin."

To all this can also be added the effect that the splendor of the ancient mosaics might have had on Dante, perhaps animating the image of Paradise that the poet constructed in his mind. Ferroni recalls that probably in the mausoleum of Galla Placidia, perhaps observing the azure vault with the golden stars dotting it and the Latin cross standing out in the center of the dome’s canopy, the poet “would have found suggestions for some of his heavenly visions, for those metamorphic movements of images with which he tries to figure paradise” (Paradiso XXIII: “e così, figurando il paradiso / convien saltar lo sacrato poema / come chi trova suo cammin riciso”). Similarly, Dante must surely have seen the images of Christ enthroned in the various Ravenna churches, such as Sant’Apollinare Nuovo or San Michele in Africisco (the latter stripped of its mosaic decoration following the Napoleonic occupation: the mosaics were dismantled and sold, and a fragment with a head of St. Michael, preserved in the Torcello Museum, came to Ravenna for the San Romualdo exhibition): images that, scholar Gioia Paradisi has suggested, could be related to St. Peter’s invective against the corruption of the Church (Paradise XXVII), in which the image of Christ’s empty throne is evoked that, by antithesis, recalls his triumph (“Those who usurp on earth my place, / my place, my place that vacates / in the presence of the Son of God”).

|

| Basilica of San Vitale. Photo Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Emperor Justinian and his procession, mosaic in the basilica of San Vitale |

|

| The mausoleum of Galla Placidia. Photo Municipality of Ravenna |

|

| The vault of the mausoleum of Galla Placidia. Photo Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Hall of the exhibition Dante and the arts at the time of exile. Photo Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Byzantine masters of San Michele in Africisco, Head of the Archangel Michael (6th century; mosaic fragment from the Byzantine church of San Michele in Africisco in Ravenna, natural stone and glass paste, 36.5 x 24 cm; Torcello, Torcello Museum). Photo by Francesco Bini |

At the time when Dante was in Ravenna, Massimo Medica again recalls, the Polentani had promoted a series of restorations and renovations of the ancient churches in order to assign a “new face to Byzantine Ravenna, as a tangible sign of the new forces at work” (so Fabio Massaccesi), an operation that drew a large number of artists and artisans to the city, so much so that Giorgio Vasari, in his Lives, went so far as to claim that Dante would act as a go-between to bring Giotto to Ravenna: “coming to the ears of Dante the Florentine poet that Giotto was in Ferrara, he operated in such a way that he led him to Ravenna, where he was in exile, and had him make in S. Francesco for the Signori da Polenta some stories in fresco around the church, which are reasonable.” The news of a Giotto being called to Ravenna at Dante’s intercession is obviously unverifiable, and it is likely, Medica explains, that it arose because of the substantial presence in the city of works by Giotto artists. A clear example of this is the splendid dossal (a Madonna and Child with Saints and four stories of Christ, which moreover underwent restoration and cleaning on the occasion of Dante and the Arts in the Time of Exile) that Federico Zeri in 1958 and Alberto Martini in 1959 ascribed to the Master of the Scrovegni Choir, an artist active in Padua in the first half of the 14th century. A work of clear Byzantine setting in the hieratic, solemn and frontal Madonna and Child, and characterized, however, by elements of Giottesque observance in the four stories of Christ (the Nativity, the Adoration of the Magi, the Crucifixion and the Resurrection) that flank the throne, it may have been made in a period situable between 1317 and the early years of the following decade (the term a quo, i.e. 1317, is motivated by the presence of St. Louis of Toulouse at the feet of the Virgin: the French saint was canonized in April of that year by Pope John XXII). The presence of Franciscan saints and the ancient Ravenna presence of this work, now kept at the MAR - Museum of Art of the City of Ravenna, suggest that it was made for the church of Santa Chiara, linked to the Da Polenta family.

“A cycle of 14th-century frescoes attributed to Pietro da Rimini,” recalls art historian Giorgia Salerno, “decorated the apse of the church, evidence of the presence of Giottesque masters in a Ravenna that, mindful of the late-antique and Byzantine splendors, under the power of Ostasio di Bernardino Da Polenta and thanks to the activity of the Franciscan and Dominican orders is in search of a new light. Therefore, the church of St. Clare cannot be ruled out as the place of origin of the panel by the Master of the Choir.” The panel is thus a testament to the interest in the arts nurtured by the Da Polenta family (who were, moreover, very devoted to St. Francis), and after all, their magnificence, the scholar recalls, had also been mentioned by Dante himself in Canto XXVII of theInferno (“Ravenna sta sta come stata è molt’anni / l’aguglia Da Poeltna la si brova / sì che Cervia la ricuopre co’ suoi vanni”).

The aforementioned Pietro da Rimini (documented from 1324 to 1338) was present in Ravenna when Dante was in town: we know from documents that the painter was employed on several occasions in decorative undertakings in the city’s churches (for example, in San Francesco and in Santa Chiara itself: the frescoes of the latter are now preserved in the National Museum of Ravenna), and he is probably also responsible for the frescoes in the refectory of the Pomposa Abbey, dating from 1318, and also perhaps admired by Dante. It is not known whether the Supreme Poet made it in time to see the frescoes in San Francesco, of which only a few fragments survive today (curiously, Pietro da Rimini also painted there a Dream of Innocent III in which the figure watching over the pope in the past was interpreted as an unlikely portrait of Dante Alighieri), but certainly the characters of what Dante could observe are similar to those that Pietro da Rimini demonstrates in a panel (datable to c. 1330) in the Vatican Museums, a Crucifixion of composed drama that Cesare Gnudi had approximated to the manners manifested by the dolenti in the frescoes of San Pietro in Sylvis in Bagnacavallo, widely attributed to Pietro da Rimini, and among the works that Dante may have been able to admire if one admits a date around 1320. Moreover, the motif of the seated St. John in the Crucifixion refers back to the figure of St. Joseph in the frescoes of St. Clare. There seems little doubt that Dante frequented the church, or at any rate knew it. “The nuns of Santa Chiara in Ravenna,” wrote Andrea Emiliani, Giovanni Montanari and Pier Giorgio Pasini in the introduction of a volume entirely devoted to the frescoes of the Ravenna church, were known to Dante "not only because they are in the spiritual direction of the same Franciscan friars with whom Dante, from 1318 to 1321, must have had familiar consortium, but because they commissioned from Pietro da Rimini those pictorial cycles so akin to the ’visible speaking’ (Purgatorio X 95) of the Poet himself in Paradise with the four Doctors, in the vault, associated with the four Evangelists; and with the twelve Saints and Saints, in the medallions of the triumphal arch, divided into six and six on each side, with a hierarchy always reminiscent of the same imaginic-creative archetypes that govern Alighieri’s poetic imagery ’Theologus dogmatis expers’ (John of Virgil) not only in the Sun cycle, with the chorus of the Twelve Doctors, but throughout Paradise."

|

| Master of the Scrovegni Choir, Madonna and Child with Saints and Four Stories of Christ (first half of the 14th century; tempera on panel, 56 x 85 cm; Ravenna, MAR - Museo d’Arte della Città di Ravenna) |

|

| The frescoes of the church of Santa Chiara, by Pietro da Rimini, preserved in the National Museum of Ravenna |

|

| The frescoes of the church of Santa Chiara, by Pietro da Rimini, preserved at the National Museum of Ravenna |

|

| TheLast Supper in the refectory of Pomposa Abbey, attributed to Pietro da Rimini |

|

| Pietro da Rimini, Crucifixion (c. 1330; panel, 24 x 16.6 cm; Vatican City, Vatican Museums) |

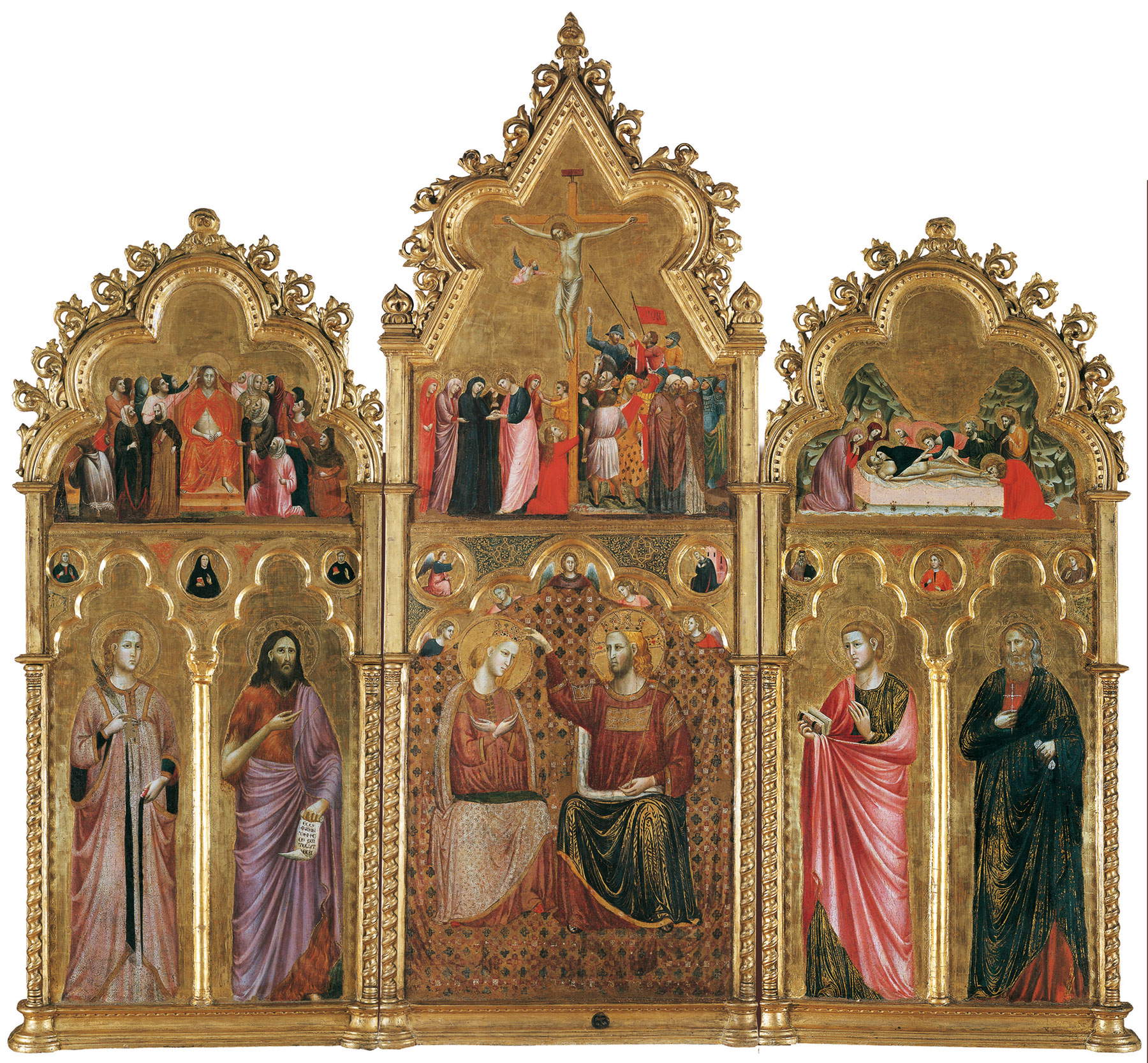

The Ravenna art scene at the time, however, was dominated by Rimini artists: another painter whom Dante may have seen is Giuliano di Martino da Rimini, better known simply as Giuliano da Rimini (documented from 1307 to 1323), another great artist of the Rimini school of Giotto, whose work the City Museum of Rimini preserves, on deposit from the Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio (which purchased it in 1996 at a Christie’s auction), a sumptuous triptych with the Coronation of the Virgin, angels, saints and scenes from the Passion of Christ, a “sophisticated weaving of Giottesque, Byzantine and Gothic elements” (so Alessandro Giovanardi), referable to a period roughly between 1315 and 1320. The documentary history of this triptych begins very late (in 1857, with a description by Gaetano Giordani that sees it in the sumptuous collection of Marquis Audiface Diotallevi, best known as he owned the Raphael Madonna named after him, the Diotallevi Madonna), which is why we do not know the work’s original provenance: the aforementioned Massaccesi’s hypothesis that the triptych came from the vanished church of San Giorgio in Foro in Rimini at the moment would seem to be the most plausible according to critical orientations. The work is one of the pinnacles of the fourteenth-century Rimini school: theCoronation of the Virgin in the central compartment, surmounted by the two roundels with theAnnunciation, is flanked by the figures of the saints (Catherine of Alexandria, Baptist, John and Andrew) according to the model of deesis (“intercession”) whereby the saints proceed toward the central scene, and is closed at the top by the cusps with the scenes of theCoronation of Thorns, the Crucifixion and the Lamentation, to create a work dense with sophisticated liturgical and theological meanings (e.g, the Eucharistic significance of the angel gathering Christ’s blood in the Crucifixion scene, or the two mountains behind the Lamentation scene, derived, Giovanardi explains, from Orthodox Easter symbolism, and signifying “the upheaval of creation following the death of the Redeemer , testified to by the Gospels and a great many passages of Byzantine and Latin liturgy, indicating the double, opposite passage both to death and Hades and to Resurrection and Ascension.”), matched by their exceptional artistic value.

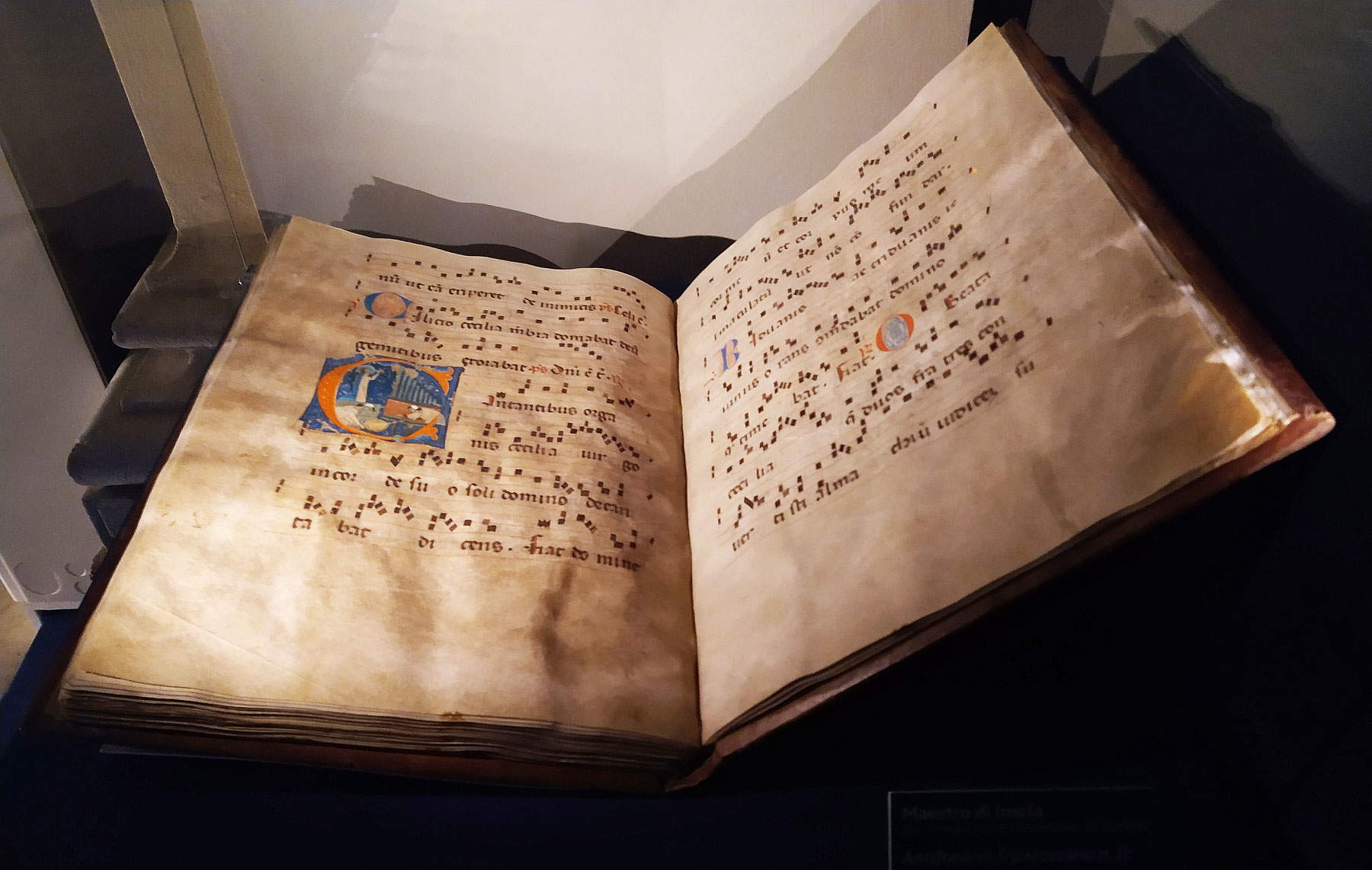

This is not a work that Dante saw (or at least we certainly cannot know), but it is a very high witness to the figurative culture in which the poet was immersed. A figurative culture in the ranks of which we can also include theart of illuminated book decoration, in which, we know for a fact, Dante had a certain interest, and in the seven hundredth anniversary of the poet’s death there is no lack of exhibitions that do not remind us of this (a review at the Museo Civico Medievale in Bologna, Dante and the miniature in Bologna at the time of Oderisi da Gubbio and Franco Bolognese, again edited by Massimo Medica, is expressly dedicated to this theme). And in the activity of cultural revitalization of Ravenna initiated by the Da Polenta family, which was mentioned at the beginning, there was no shortage of commissions concerning the art of illumination: among the most relevant are the antiphonaries now in the Diocesan Historical Archives, which falls within the framework of those operations “in line with the artistic taste that spread in the Po Valley area between the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, always poised between classical cues, Byzantine reminiscences and Gothic novelties” (so Paolo Cova). The antiphonaries were destined for the church of San Francesco: these are five volumes dating from the period 1280-1285, and thus to a time shortly after the installation of Lavagna bishop Bonifacio Fieschi (in 1276). The antiphonaries are due to the Master of Imola, a refined author who was well acquainted with Tuscan book production and who, at the time of the Ravenna works, explains Paolo Cova, “must have developed a prestigious and narrative lexicon, characterized by a greater expressive tension than the more typical formal outcomes of the ’first style,’ capable of adapting to a vast and diversified production.” In Antiphonary II the artist demonstrates characters of great refinement, permeated by a subtle naturalism and close to the innovations introduced by Cimabue, revealing how the miniature was very receptive to what was being produced in the pictorial disciplines. Dante, of course, was up to date with the results of book production, as we learn from the famous passage on Oderisi da Gubbio in the 11th canto of Purgatory.

|

| Giuliano di Martino da Rimini, Coronation of the Virgin, Angels, Saints and Scenes from the Passion of Christ (c. 1315-1320; tempera and gold on panel, 225 x 240 cm; Rimini, Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio, on deposit at the City Museum) |

|

| Giuliano di Martino da Rimini, Coronation of the Virgin, angels, saints and scenes from the Passion of Christ, detail |

|

| Master of Imola, Franciscan Antiphonary No. II, summer sanctoral (1280-1285; membranaceous, 505 x 355 mm; Ravenna, Diocesan Historical Archives) |

|

| Venetian-Ravenna master, Madonna Enthroned with Child (late 13th century; marble, 93.5 x 51.5 x 19.5 cm; Paris, Louvre) |

Finally, it is interesting to mention the singular case of a work of art from Dante’s time that was reused centuries later for his burial. It is a Madonna and Child Enthroned in marble now in the Louvre: it is the work of a Venetian-Ravenna master educated on Byzantine models, as the frontality of the group attests, but not without volumetric values that are more akin to Romanesque sculpture from the Po Valley area, such as that of Benedetto Antelami. A mixture that makes this object particularly interesting, although we do not know where it was originally located. It seems, however, according to a hypothesis formulated in 1921 by Corrado Ricci, that this was the Madonna and Child that surmounted Dante’s original tomb, in a small chapel next to the basilica of San Francesco in Ravenna, in the place where we now find Dante’s present tomb, designed in 1780-1781 by architect Camillo Morigia. It was Morigia himself who removed the Madonna from the ancient chapel, placing it in the new public school building on today’s Via Pasolini. After the removal, traces of the work were lost until 1860, when it was purchased by the French collector Jean-Charles Davillier: later, in 1884, the marble relief, along with many other works in the Davillier collection, became part of the Louvre’s collections following a donation. And, as recalled, it was Ricci who identified it with the Madonna that once adorned the poet’s funeral chapel.

A work, in short, pregnant with meaning and suggestion: it is a bridge between the time when Dante was alive and visiting the churches of Ravenna, and the post-mortem celebration of the poet, with the various and repeated pilgrimages of the great personalities (men of letters, artists... ) who passionately went to Ravenna to remember Dante at his tomb. A cult that was gaining momentum just shortly after Morigia’s reconstruction of the tomb, and which saw one of its earliest and highest moments in Foscolo, in the Last Letters of Jacopo Ortis. The Foscolo character did not have time to see the marble Madonna (for a few years), but the passion that will inspire his extreme gesture constitutes one of the highest tributes that literature has reserved for the Supreme Poet: “Sullurna tua, Padre Dante! Embracing her, I set myself even more in my counsel. Mhai tu veduto? mhai tu forse, Padre, ispirato tanto fortezza di senno e di cuore, mentrio genuflesso, con la fronte appoggiata a tuoi marmi, meditated e l’alto anima tuo, e il tuo amore, e lingrata tua patria, e lesilio, e la povertà, e la tua mente divina? And I escompagnato dall’ombra tua più deliberato e più lieto.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.