WithRenaissance Humanism came a renewed interest in antiquity and the spread of a culture that took its cue from the discoveries made through the numerous translations of Greek and Latin texts. The acquisition of the new knowledge relating to various fields of knowledge and in particular relating to the individual, both of his mere constitution and the essence of his soul, led to fixing thehuman being at the center of the world. Study, investigation and experimentation were the most innovative aspects of the culture of the time, and this caused man himself to become an object of observation and reflection.

Testimony to this consideration is the abundance in that era of portraits: in fact, between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, artists took as models for their works a plethora of well-known figures, such as the exponents of the various seigniories that held control of different areas of Italian territory, but also those who were part of the people, those we would call ordinary people. However, often men and women who revolved around the most powerful families, the lords of the Renaissance courts, were more likely to be immortalized in the paintings and sculptures of artists, since the latter used to frequent the rich residences of the lords, and it was also common for them to be “hired” as official court painters or artists. Courts thus became places of dissemination of the new humanistic culture, where principles, knowledge, and discoveries were promulgated through artists and personalities from the cultural world, from the literary to the scientific.

Among the personalities who worked in one of the most influential courts of the Renaissance, that of the Sforza family in Milan, mention must be made of Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci, 1452 - Amboise, 1519): the great genius, who moved from Florence to Milan, spent more than a decade of his existence, from 1482 to 1499, in the Sforza court, when the lordship was in the hands of Ludovico il Moro (Vigevano, 1452 - Loches, 1508). During those years Leonardo painted some of his greatest masterpieces: the Portrait of a Musician, the Lady with an Ermine, and La Belle Ferronniè;re. The first was made in about 1485 and is now preserved at the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana in Milan: it was initially thought that the subject portrayed was Ludovico il Moro himself, but when, thanks to the 1905 restorations, a musical scroll appeared in the man’s hands, it was realized that he was a musician; several identities have been hypothesized so far: Franchino Gaffurio, maestro di cappella of Milan Cathedral; Josquin Desprez, a Flemish cantor at the court of Ludovico Sforza; and Atalante Migliorotti, a musician friend of Leonardo who came to Milan as a singer and lyre player. The Lady with an Ermine can be dated between 1488 and 1490 and can currently be seen in the National Museum in Krakow; the female figure depicted has been identified as Cecilia Gallerani, Ludovico’s young lover. The identification would also be confirmed by theermine that the girl holds in her arms, since the word ermine in Greek is translated galé, thus recalling the girl’s surname.

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Portrait of a Musician (c. 1485; oil on panel, 44.7 x 32 cm; Milan, Veneranda Biblioteca and Pinacoteca Ambrosiana) |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Lady with an Ermine (1488-1490; oil on panel, 54.8 x 40.3 cm; Krakow, National Museum in Krakow) |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Portrait of a Lady known as La Belle Ferronnière or alleged portrait of Lucrezia Crivelli (1493-1495; oil on panel, 63 x 45 cm; Paris, Louvre) |

In creating the Portrait of a Lady, known as La Belle Ferronnière, Leonardo da Vinci did not merely depict the social position of the lady; rather, he wanted to draw real emotions out of the canvas and convey them to the viewer. In Leonardo’s Treatise on Painting we read, “True it is that the signs of faces show in part the nature of men, their vices and complexions [...] You shall make the figures in such an act, which is sufficient to show what the figure has in its soul; otherwise your art will not be laudable.” Indeed, one can see in the famous painting a meticulous naturalistic rendering in terms of color, but especially in theexpression and gaze of the maiden. A face that fascinates, and that inevitably leads the relative to observe it deeply: anyone who stands before it to admire this masterpiece of the great genius, as well as one of the most beautiful masterpieces in the history of Italian art, will be captivated by the fineness and cool naturalness of this gaze. The muted pink tones of the lady’s cheeks heighten the naturalistic rendering of the portrayed figure even more: it thus seems as if one is not vis-à-vis a person painted on the canvas, but rather seems to be on the verge of interacting with a real, living person.

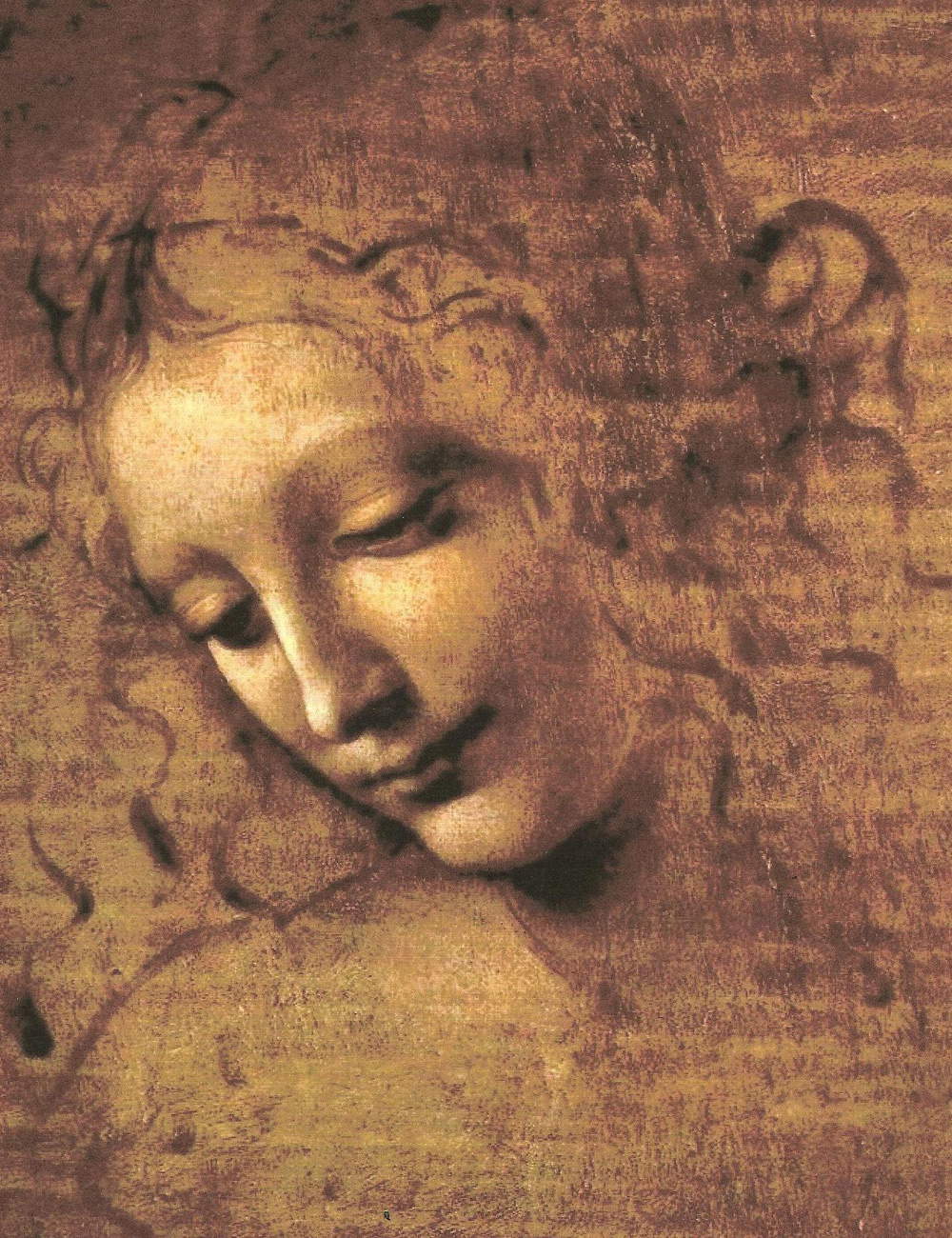

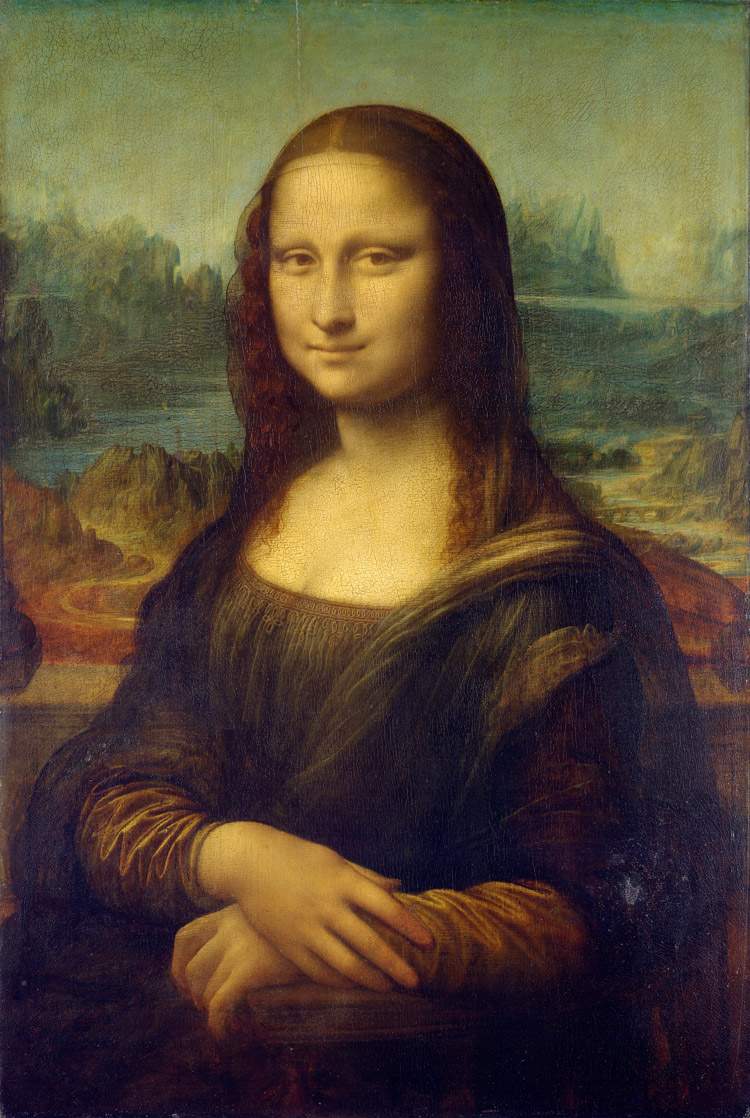

This is precisely Leonardo’s ability, that is, to portray human figures always keeping in mind the naturalistic studies, which he had already made in Florence and which he brought with him to the Milanese area, spreading such knowledge. His portraits are often the result of various studies before arriving at the final realization, one thinks of the Head of Leda, and they are generally united by these looks that “speak”: think of the Mona Lisa, the Scapigliata, although later, or the already mentioned Lady with an Ermine, as well as precisely the Belle Ferronniè;re. The Da Vinci artist gave significant importance to the eyes and the gaze, since these express thesoul of the person himself.

|

| Leonardo da Vinci (with later takes?), Study for Head of Leda (c. 1505-1506; natural red stone on red-pink prepared paper, 200 x 157 mm; Milan, Civico Gabinetto dei Disegni del Castello Sforzesco) |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Head of a Woman Called the Scapigliata (c. 1504-1508; earth shadow and amber inverdita lumeggiata di biacca on panel, 24.7 x 21 cm; Parma, Galleria Nazionale) |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, The Mona Lisa (c. 1503-1513; oil on panel, 77 x 53 cm; Paris, Louvre) |

La Belle Ferronnière is depicted seated, half-length, and turned three-quarters: although the maiden’s gaze appears to be directly facing the viewer, it is actually slightly shifted. This is almost imperceptible, but the eyes of the lady never meet the eyes of the observer. The latter is forced to shift to the right to fully grasp the direction in which the figure is looking: it is in fact an elusive, moving glance. In this regard, the British art historian Martin Kemp has noted how this particular position of the figure and the ambiguously averted gaze lead one to liken it to a sculpture, around which the observer would be led to turn, in an attempt to cross those elusive eyes. This is an expedient that expresses the dynamic sense of volume and is more pronounced in this work than in other portraits completed by Leonardo, as in the case of the Lady with an Ermine, whose face and gaze is evidently turned to her left, in the act of staring at a definite element, off the canvas.

Leonardo da Vinci trained in the workshop of Verrocchio (Andrea di Cione, Florence, 1435 - Venice, 1488), whose activity as a sculptor was more significant than as a painter: he revealed to his pupil the possibility of applying the principles of sculpture to painting and drawing: space, volume and multiplicity of viewpoints. In his workshop, painting and sculpture dialogued: plastic models were used in painting and pictorial specimens could be used for three-dimensional works. La Belle Ferronnière has sculptural characters in it, and it is evident if we compare it with Verrocchio’s Lady with a Bunch . The latter was made by Andrea del Verrocchio between 1475 and 1478, and is now housed in the Museo Nazionale del Bargello in Florence. In the Lady with the Bunch , the naturalism of the face and gesture is grasped, just as the face of the Belle Ferronnière is natural, and in the latter, the strong plastic valences can be seen: thus, the mentioned interchange between painting and sculpture is confirmed through a comparison of the two works mentioned above, giving three-dimensional valence to the painting and at the same time a pictorial treatment to the sculpture.

In Belle Ferronnière, the sense of space is also perceived thanks to the balustrade that stands between the lady and the viewer and thanks to the dark but shaded background against which the portrait is silhouetted. The viewer of the painting is suggested by the impression that that dark background is a fairly large room, bounded frontally by the balustrade, beyond which the maiden is turning her gaze. However, the lady is illuminated by a warm light, which makes her skin heat-sensitive and creates a play of light and shadow on the robes of the precious fabric. In the rosy reflection glimpsed on the left cheek, there is a perceivedapplication of the studies of optics and the studies of shadow and lume of the early 1590s, and in particular the studies of colored shadows.

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, La Belle Ferronnière, detail of the face |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, La Belle Ferronnière, detail of the jewel |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, La Belle Ferronnière, detail of the robe |

|

| Verrocchio, Lady with a Small Bunch (1475-1478; marble, height 61 cm; Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello) |

The maiden wears a red dress with a square neckline, decorated with gold trim; the gold color is also found in the ribbons that tied in bows adorn the sleeves, which according to the fashion of the time were removable; below the sleeves appear the puffs of a white shirt. Her neck is embellished with a necklace that falls over her breast, knotted to a ribbon. Her hair is gathered in a typical Renaissance style: parted in the center and tied in a low ponytail covering her ears. Around the head one notices a kind of thin thread that holds a small jewel placed in the center of the forehead. This jeweled chain was used extensively by ladies in the late fifteenth century and, in addition to adorning the forehead, was very useful for holding the hairstyle firmly in place: it is from the painting that this jewel was named “ferronnière.” The name by which the work is known, literally “the beautiful wife of the ironmonger,” is the result of an error made in an eighteenth-century cataloguing, according to which the lady portrayed depicted Madame Ferron, mistress of Francis I of France.

Regarding the true identity of the girl, several names have been advanced over the years: Cecilia Gallerani, the same maiden whom Leonardo had portrayed in the Lady with an Ermine, perhaps at an older age than the painting in the National Museum in Krakow; Beatrice d’Este, wife of Ludovico il Moro. The lady was later identified, gaining some critical acclaim (though not unanimously), with Lucrezia Crivelli, Beatrice d’Este’s lady-in-waiting and mistress of Ludovico himself, who bore him a son in 1497. The painting is said to have been recognized in three unpublished epigrams by Antonio Tebaldeo (Ferrara, 1462 - Rome, 1537), recorded in the Codex Atlanticus: the second epigram reads “Huius quam cernis nomen Lucretia, Divi / Omnia cui larga contribuere manu. / Rara huic forma data est; pinxit Leonardus, amavit / Maurus, pictorum primus hic, ille ducum.” This is a correspondence that has been emphasized recently, thanks mainly to the work of art historian Carmelo Occhipinti, who has devoted important pages to the relationship between the couplets of the Codex Atlanticus and the portrait: according to the scholar, Leonardo preferred “that the portrait of Lucretia had no soul” (because as of a soulless woman Tebaldeo speaks of it in the first epigram) so that “it was nothing more than a painting, however resembling, thus renouncing to make it, prodigiously and paradoxically, a true living creature on a par with the real Lucretia.” In other words, Occhipinti explains, "none of us, in front of Lucrezia’s portrait, would be able to take possession of Lucrezia’s soul, for the simple and obvious reason that Lucrezia does not look at us. Lucretia is not ours. Her eyes are not for us; they do not meet ours. They escape us. They look elsewhere. If Leonardo had painted them facing us exactly, we would not have been able to withstand so much splendor directly emanating from Lucrezia’s soul: Leonardo thus intended to defend the observer from the power of Lucrezia’s beauty and her inner richness, also showing himself, in doing so, to be maximally respectful towards Ludovico il Moro and his love for Lucrezia.“ As Pietro Marani also remarked, Tebaldeo’s was a ”most subtle literary acrobatics in honor, at one and the same time, of Ludovico il Moro and Leonardo, comparable to a veritable ecfrasis."

The work was completed, as already stated, during Leonardo’s years in Milan, more precisely between 1493 and 1495. On Leonardo’s authorship there are no longer any doubts: the work, which was the subject of heated critical debate between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the next (at the time there were distinguished scholars who preferred to assign it to others: Gustavo Frizzoni and Bernard Berenson, for example, ascribed it to the hand of Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, although Berenson later recanted and argued in favor of Leonardo), was then almost unanimously assigned to Leonardo (the only dissenting voices being those of Jack Wasserman in 1975 and that of Sylvie Béguin in 1983) to be firmly confirmed in 2007 in the Louvre’s catalog of paintings. Indeed, the work is now part of the Louvre’s Paris collections. Currently, however, it has been transferred to the Louvre Abu Dhabi, the museum that the Louvre in Paris opened in the UAE capital in November 2017: the painting will remain there for a period of time as part of a loan program, arousing quite a bit of controversy in the international cultural world.

Reference bibliography

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.