“One day in September 1802, a small group of Greeks, Turks and British gathered on the Acropolis. They had arrived to witness the removal of a metope from the Parthenon structure, a carved panel depicting a woman abducted by a centaur.” This is how scholar Christopher Hitchens describes the beginning of the removal of the Parthenon marbles by the British: eventually, about half of the surviving sculptures in the great temple of Athena would make their way to London, and which had been in situ since 432 B.C., on the two pediments of the great building that towers over theAcropolis in Athens, and along the friezes on the four sides. The modern history of the Parthenon marbles, however, can be made to begin even further back, at least from 1458, when the city of Athens was captured by the Ottomans, who had conquered Constantinople five years earlier and had begun to push into the interior of Greece: by 1460, all Greek territory had come under Ottoman control.

Until the time of the Turkish conquest, the temple had not suffered great losses. It had remained virtually intact until the 3rd century: it suffered its first serious damage in 276, during the Heruli invasion, but was later restored. After Theodosius II’s edict of 435, which stipulated the closure of all pagan temples in the Roman Empire, the Parthenon was closed to worship (although it is likely that the actual closure came much later, perhaps in the 480s), while in the 6th century it was converted into a Christian church, a function it held until the Turkish conquest, after which it was converted into a mosque. Over the centuries, the Parthenon had already suffered the removal of a number of statues, and although there was no intention on the part of the Ottomans to destroy the temple (in fact, the Turks did not take care to protect the monument, but neither did they have nefarious intentions), it was during Ottoman rule that the Parthenon suffered the most damage. In 1687, during the Morean War, the Ottomans set up an ammunition depot inside the Parthenon, hoping that the Venetians, out of respect for a monument that had also been a church in ancient times, would not attack it: their predictions turned out to be wrong, since during the siege of Athens the Venetians’ bombardment did not spare the Parthenon, and their cannons damaged it heavily, causing the central part to collapse. Even today we see the Parthenon with the marks of the damage inflicted by the Venetians’ cannonballs. The Ottomans did not restore it, but after the war ended the still functional part of the temple continued to be used as a mosque. The captain-general da mar (i.e., the commander of the Venetian fleet), Francesco Morosini, was ordered by the Venetian Senate to bring the best sculptures to Venice: due to logistical problems (the Venetian genius did not have the proper equipment to remove such large sculptures and transport them), the Venetians only further damaged the statues, shattering some of them. It was therefore possible to carry away only a few fragments: the most important portion of the Parthenon decorations removed by the Venetians is the so-called “Weber-Laborde head,” a female head now in the Louvre (in the 19th century it ended up in the collection of the German merchant David Weber, and was later sold by him to Count Léon of Laborde, and finally purchased by the Louvre in 1928). Other smaller fragments among those removed during the Venetian attempt were reused partly as building material, and partly ended up in private collections, and from these later in some museums (three fragments are also found in the Vatican Museums). However, most of the sculptures of the pediments had remained in place even after all these events.

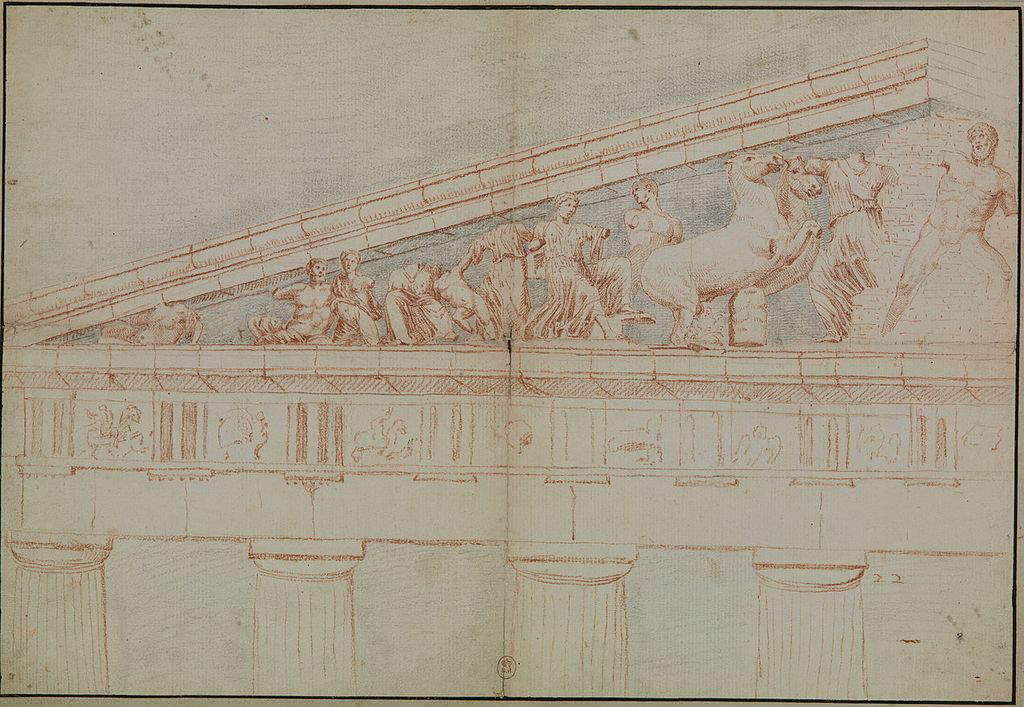

The two pediments of the Parthenon were decorated with two rich complexes of statues, executed between about 440 B.C. and 432 B.C. by Phidias with the help of his workshop: they are considered great masterpieces of classical Greek sculpture. The statues have come down to us in fragmentary condition, and several artists worked on the complex, although the sculptures find their own harmony in the unity of the design conceived by Phidias. We know the themes of the decoration from the rich description provided in the second century CE by Pausanias the Periegeta, a writer, geographer and traveler who, on his way to Athens, dwelt in detail on the statues of the Parthenon pediment, which were so remarkable that they alone were enough to evoke the great temple (of the Parthenon only these sculptures are in fact described). On the east pediment, the iconographic design had envisioned the depiction of the myth of the birth of Athena, delivered from the head of Zeus: the central group, which depicted precisely the birth of the goddess of wisdom, has been lost. On either side of it were sculptures of the gods who had witnessed Athena’s birth, although these were difficult to identify. Finally, at either end stood the depictions of Helios and Selene, the sun and moon gods driving their respective chariots, symbolizing the time space in which the story had unfolded.

The west pediment depicted the struggle between Athena and Poseidon for control of Attica, won by the goddess. With groups with a more pressing rhythm than those on the eastern pediment, Phidias had imagined the story by arranging in the center the figures of the two struggling (lost) gods, followed by the chariots, complete with rearing horses on their hind legs, led by the deities arrayed on either side (Hermes and Nike with Athena, Iris and Amphitrite with Poseidon), while other gods were depicted following their respective processions. At the ends, to suggest the place of contention, Phidias had arranged reclining statues of Cephysus and Ilissus, personifications of two rivers of Attica. As mentioned, the central groups were lost: some drawings made in 1674 and traditionally attributed to Jacques Carrey, an artist in the service of the Marquis de Nointel, French ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, show that by that date the pediments had already suffered extensive damage, and further destruction would have been suffered during the Venetian bombardment and the subsequent attempt to bring the best sculptures to Venice. If the Venetians had failed, a century later would come those who instead successfully completed the mission of removing the Parthenon sculptures: the English diplomat Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin (Broomhall, 1766 - Paris, 1841), who in 1798 had been appointed British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire.

We do not actually know Lord Elgin’s original intentions. What is certain, wrote scholar Robert Browning, is that Elgin found himself in “a position of unprecedented privilege, for after the defeat of the French fleet at the hands of Lord Nelson at the Battle of the Nile in August 1798, the sultan [Selim III, ed.] looked to Britain to protect the Ottoman Empire from France. As a result, Elgin was able to obtain a signan [an Ottoman royal decree, ed.] from the sultan’s ministers, authorizing him to make casts and drawings of the sculptures placed in the ’temple of idols’ in order to carry out excavations to search for fragments, and to remove ’certain stone parts with inscriptions and figures.’” According to Browning, it has never been clarified, given the vagueness of the document (moreover, the original has been lost), whether the signatory was to be understood as an authorization to remove as many sculptures as Elgin wanted, but in fact this was indeed the case: in the spring of 1801, with the supervision of the work entrusted to the painter Giovanni Battista Lusieri (Rome, 1755 - Athens, 1821), recommended to him by the archaeologist William Hamilton, the British diplomat first had fifty entire reliefs removed from the frieze, in addition to two others that had half survived, and fifteen metopes. The frames, during the operations, suffered significant damage.

Later, Elgin began to have the sculptures in the pediments removed as well: indeed, the diplomat had stated during his visit to Athens in the summer of 1802 that the sculptures were in danger of suffering further damage, and therefore should be removed to ensure their preservation. However, Browning writes, “Elgin’s men had begun removing sculptures and packing them for transport as early as six months before his first and only visit to Athens, in the early summer of 1802. His unprecedented privileges seem to have gradually pushed him morally and aesthetically beyond his means.” Expeditions to England began in 1803: eventually, 39 metopes, 56 frieze reliefs and 17 pediment statues left for the British Isles. At first, the sculptures were kept in the residence of Lord Elgin, who decided to open his collection of Parthenon marbles starting in 1807 by invitation. The exhibition was a huge success among the many lovers of ancient arts. But there was also much criticism even at the time: the poet George Byron thought Lord Elgin was a vandal, and in 1812 he published a poem, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, in which he briefly offered his views on the matter: “O beautiful Greece, cold is the heart of he who looks upon thee / and does not feel like the lover on the urn of his beloved, / blind is the eye that will not weep to see / thy walls in ruins, thy shrines plundered / by British hands that would have behaved better / if they had guarded those relics that would never be restored. / Cursed be the hour when they left their island.” Other poets who attacked Lord Elgin include Horace Smith, John Galt and John Hamilton Reynolds (the latter, in one of his satirical writings, called Lord Elgin’s “Greek depredation” a “robbery”).

Other intellectuals of the time were heavily critical: the politician John Newport said that Elgin had “taken advantage of the most unjustified means and carried out the most flagrant plunder,” and he considered it “execrable” that “a representative of our country should have plundered those objects which the Turks and other barbarians had considered sacred.” And again, the painter Edward Dodwell, also an eyewitness, had expressed his “mortification at having been present when the Parthenon was being stripped of its most beautiful sculptures,” with the result that the temple was no longer “a picturesque beauty in an excellent state of preservation,” but had been “reduced to a state of shattered desolation.” Naturalist Edward Daniel Clarke, who had been an eyewitness to the removal of the metopes, had called the operation a “despoliation,” and believed that the temple had suffered more damage from Elgin than from Venetian bombardment. Contemptuous was the scientist Francis Ronalds, inventor of the first electric telegraph, who wrote in 1820 that “if Lord Elgin had really had good taste instead of a greedy spirit, he would have done exactly the opposite of what he did, and that is, he would have removed the debris and left the antiquities.” Few were those who greeted Elgin’s action positively: the most prominent name was Benjamin Robert Haydon, a painter and antiquities enthusiast, who enthusiastically hailed the Parthenon’s collection of marbles. The poets John Keats and William Wadsworth, on the other hand, merely commented on the beauty of the marbles but did not enter into the querelle over the legitimacy of the operation. On one point, however, they all agreed: to avoid restorations that today we would call "integrative." In fact, Lord Elgin had approached Antonio Canova in 1803 to ask if there was any possibility of restorations with touch-ups: Canova expressed strong opposition, explaining that those works “were the work of the ablest artists the world had ever known” and that “it would be a sacrilege for anyone to presume to touch them with a chisel.” Even John Flaxman, prompted by Canova if Lord Elgin had really wanted to get his hands on the sculptures, provided his own objections. Haydon himself objected, believing that any restoration would detract from the beauty of the sculptures.

A parliamentary commission of inquiry was also established to investigate Lord Elgin’s actions: the outcome was favorable toward the diplomat, since parliament had come to the conclusion that the marbles looked better in a “free” country as the United Kingdom was considered at the time. The British Museum expressed almost immediately, that is, from 1810, its desire to purchase the collection, although negotiations at first were hampered by the amount the nobleman asked for, which was considered too exorbitant. A kind of opinion movement was created that supported the British, since the sculptures were fragmentary, and it was felt that it was not worth paying more than 60,000 pounds for these sculptures. In the end, the transaction took place in 1816, for the sum of 35,000 pounds (the equivalent of about 2.3 million euros today), roughly half of what the diplomat had spent to have the works brought to his home, after a further parliamentary committee, set up this time to assess the fairness of the purchase, ruled favorably. The works were shown to the public from 1832 in the “Elgin room”: from that time, the Parthenon marbles became the "Elgin marbles." They remained in this room until 1939, when the Duveen Gallery was completed, a room specially built to house the Parthenon marbles, and where they can still be seen today.

In recent years, a broad opinion movement has emerged promoting a campaign for the return of the Parthenon Marbles to Greece. One can pinpoint 1981 as the starting date of the campaign: an “International Organizing Committee” for the return of the Parthenon Marbles was established on that date in Australia, followed in 1983 by the creation of a British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles. Both committees are still operational today. The position of those who would like the return of the marbles to Greece can be summarized in at least four basic points: the legitimacy of the acquisition, theintegrity with the context, the symbolic character that the marbles hold for Greece, and the precedents.

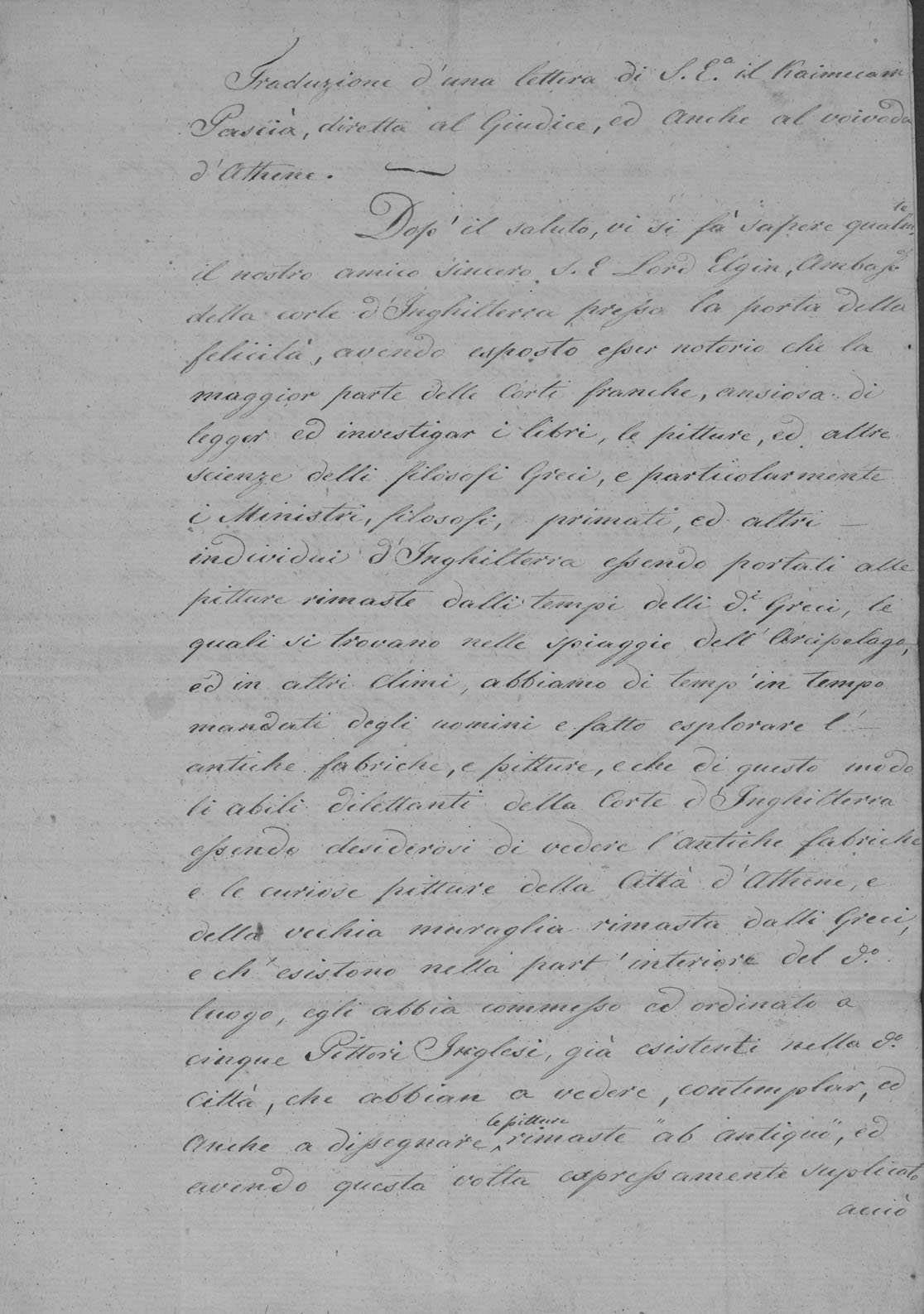

The legitimacy of the acquisition is certainly the most controversial point. The problem lies in the fact that, despite numerous searches, the original signanum granted to Lord Elgin has never been found. To date, we know only an Italian translation of the signanum, which was preserved by Reverend Philip Hunt, Lord Elgin’s chaplain, and was acquired by the British Museum in 2006. The translation is included in a letter from Sejid Abdullah, who in December 1799 had been appointed Kaimakam (i.e., Acting Grand Vizier), and who can be considered the second highest office in the state after the sultan. The letter was addressed to the Cadi and Voivoda of Athens, chief justice and governor of the city administration, respectively. It was translated into Italian by a certain Antonio Dané, as attested in a letter from Hunt dated July 31, 1801. “Our sincere friend, H.E. Lord Elgin, Ambasc.e of the Court of England at the Gate of Happiness,” the translation reads, “having exposed it to be notorious that most of the Frankish Courts, anxious to read and investigate the books, paintings, and other sciences of the Greek philosophers, and particularly the Ministers, philosophers, primates, and other individuals of England being taken to the paintings remaining from the times of d.The Greeks, which are to be found in the beaches of the Archipelago, and in other climes, we have of time sent men and made them explore the ancient fabrications, and paintings, and that by this means the able amateurs of the Court of England being desirous of seeing the ancient fabrications and curious paintings of the City of Athens, of the old wall remaining from the Greeks, and whichsist in the partinteriore of the d.or place, he hath committed and ordered to five English Painters, already existing in the said City, that they should have to see, contemplate, and also to draw [the paintings] remaining ab antiquo, and having this time expressly suplicated so that it may be written and ordered that to the said painters, while they shall be occupied colintrar and exit from the gate of the Castle of the d.a City, which is the place of observation, by forming the stairways around the ancient temple of the Idols, by extracting from the lime (i.e. plaster) the same ornaments, and visible figures, by measuring the leftovers from the other ruined buildings, and by undertaking to excavate as needed, the foundations to find the inscribed bricks, which were left inside the gravel, will not be inconvenienced, nor made an obstacle.o on the side of the Castelano, nor of verunaltro, and that they not singerisca in their stairways, and instruments, which will have formed there; and when they wanted to take away some pieces of stone with vechie inscriptions, and figures, not be made themoposizione [....] since there is no harm in having the aforesaid paintings and fabrications seen, contemplated, and drawn, and after having been accompanied by the appropriate welcome of hospitality towards the above-mentioned painters, in consideration also of the friendly request on this particular one had received, from the aforesaid Amb.King, and in order to beincompatible that no opposition be made to the walking, seeing and contemplating of the same the paintings, and fabrications that they will want to draw, nor to their stairways, and instruments, allarrivo of this letter usiate attention.”

From the form in which the translation is written, scholars have inferred that it is evidently a summary of the original document: there are in fact abbreviations, the names of those in charge are not mentioned, the same greetings are addressed in abbreviated form, and in addition the fact that the document bears the seal of the Kaimakam and not that of the sultan indicates that it is an unrelated document to a possible signan, on which the seal of the sultan was instead affixed. In essence, according to Professor Vassilis Demetriades, professor of Turkish studies at the University of Crete, no document among those that have survived can be assimilated to a signanum. Strong doubts remain, therefore, about the nature of the original document, which never reached England: during the 1816 investigation, in fact, Elgin was asked for the documents, but the diplomat claimed that the original copies had been delivered to the Ottoman authorities in Athens. Despite the major gaps and the impossibility of consulting the Ottoman documentation, the committee nevertheless ruled favorably.

The debate over the legitimacy of the acquisition, however, also calls into question the Italian translation, in the controversial passage in which it is said that “when they wanted to take away some pieces of stone with vechie inscriptions, and figures, let them not be made theiroposition”: according to those who argue the illegality of the operation, it is clear that the locution “to take away some pieces of stone” implies that the authorization was limited to a few fragments. However, this is an ambiguous translation, since the term “figures” could refer to any figures carved on the “pieces of stone,” on a par with the “old inscriptions,” but it could also mean “sculptures,” and in this case the locution would be unrelated to the adjective “a few.” Then there are also those who, like law professor David Rudenstine, have advanced the hypothesis that Elgin and his associates forged the documents submitted to the 1816 commission. The situation is therefore very smoky, and those who support the return to Greece are wont to leverage these arguments to point to the acquisition as illegitimate.

The second reason is that ofintegrity: “the Parthenon Marbles,” explains the British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles, “are not independent works of art, but integral architectural parts of one of the most magnificent and well-known monuments in the world.” For this reason, “it is inconceivable that more than half of its celebrated sculptural elements should be displayed two thousand miles away from the monument for which they were expressly designed and sculpted.” It should be noted that, for preservation as well as historical reasons, it would be impossible to relocate the sculptures to their proper place: the Parthenon statues are very delicate, have suffered damage even at the British Museum (due to pollution and the cleaning methods used by 19th-century restorers), and consequently, if exposed to the open air, would risk rapid and nefarious deterioration. Moreover, to put them back in their place would mean erasing two centuries of history: the empty pediments are very eloquent witnesses to what the Parthenon underwent in the early 19th century. However, this does not mean that the marbles cannot return to Athens, thus at least finding their historical, cultural and geographical context.

There are also symbolic motivations. “The Parthenon is the most important symbol of Greek cultural heritage, and according to the Declaration of Universal Human and Cultural Rights, the Greek state has a duty to preserve its cultural heritage in its entirety, both for its citizens and for the international community,” the British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles further emphasizes. “Therefore, the request for the reunification of the sculptural elements of the Parthenon is ipso facto a just if not legitimate request.” Again, it insists that when the marbles were removed, Greece was occupied by the Ottomans, and the Greek people never gave their consent for the removal of the sculptures. Moreover, the Committee further notes, the Parthenon “was erected to celebrate the victory of Athenian Democracy, which encouraged the creation and development of all the arts as well as politics, philosophy, theater and even science as we know them today. Thus, the Parthenon is a celebration of the achievements of free and democratic people and for this reason it is an important symbol for the whole world.” For this reason, too, the marbles should be brought together, according to those who support this thesis.

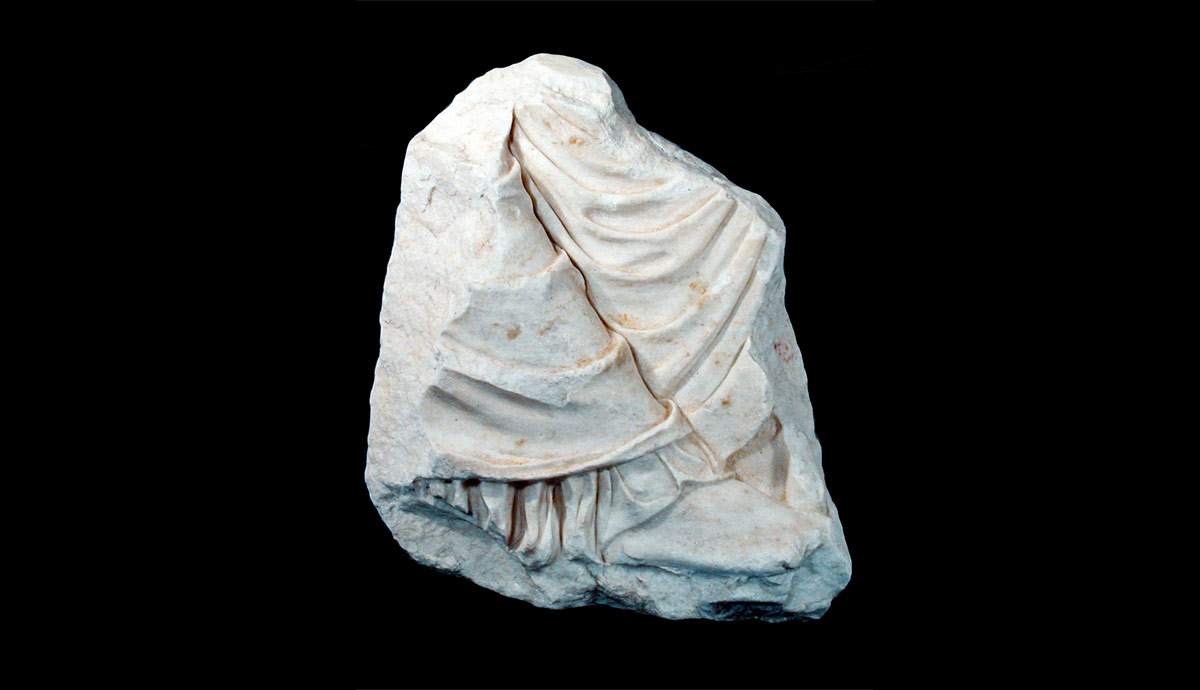

Finally, the precedents: there are many countries that have initiated cultural decolonization processes in recent years, and now returns of works of art to the countries from which they came are commonplace and often also involve legitimately acquired works. However, there is a very important precedent concerning the Parthenon itself: the case of the Palermo fragment, also known as the Fagan Exhibit. It is a fragment of a slab from the eastern frieze of the Parthenon, depicting the foot of the goddess Peitho or Artemis seated on a throne, and until early 2022 kept at the “Antonino Salinas” Archaeological Museum in Palermo. It was given in 1816 by Elgin to Robert Fagan, a collector of antiquities: after his death in 1820, his collection of antiquities flowed to the Museum of the Royal University of Palermo, the “father” of the Salinas Museum. In January 2022, the Region of Sicily and Greece had reached an agreement for an eight-year loan of the fragment to the Acropolis Museum in Athens: in return, Greece stipulated that it would lend Italy a headless statue of Athena from the fifth century BC and a geometric amphora from three centuries earlier. However, the will of Sicily was to return the fragment to Greece: a decision that actually came in May 2022, with the agreement between Sicily and Greece, to which Italy’s Ministry of Culture gave the go-ahead, granting the region permission for the final export. The Palermo fragment has thus been returned to Greece, and this act constitutes, according to experts, the most important precedent for the return of the so-called Elgin marbles, and could possibly unblock the situation.

The British Museum ’s position, however, has always been strongly against the return, and is reiterated by the museum in a statement by its trustees listing all the reasons for the opposition. Meanwhile, according to the British Museum, Lord Elgin “acted with the full knowledge and permission of the legal authorities of the time in both Athens and London. Lord Elgin’s activities were thoroughly studied by a parliamentary committee in 1816 and found to be entirely legal. Following a vote of Parliament, the British Museum was allocated funds to acquire the collection.” Again, on the point of integrity with context, the British Museum argues that “Europe’s complex history has often led to the division and distribution of cultural objects, such as medieval and Renaissance altarpieces from an original place, across museums in many countries. Reuniting the Parthenon sculptures into a unified whole is impossible. The complicated history of the Parthenon meant that by the 19th century about half of the sculptures had been lost or destroyed.” The trustees then believe “that it is a great public benefit to see the sculptures in the context of the British Museum’s world collection in order to deepen our understanding of their significance within world cultural history. This provides an ideal complement to the display in the Acropolis Museum. Both museums together enable the fullest understanding of the meaning and importance of the Parthenon sculptures and maximize the number of people who can appreciate them.” Ultimately, according to the British Museum, “the approach of the Acropolis Museum and that of the British Museum are complementary: the Acropolis Museum offers an in-depth view of the ancient history of its city, the British Museum offers a sense of the broader cultural context and prolonged interaction with the neighboring civilizations of Egypt and the Near East that contributed to the unique achievements of ancient Greece.” For these reasons, the museum says it is right for the Parthenon sculptures to remain in England. Opponents then advance other reasons: the fact that many more people in London see the sculptures (the British has about five times as many visitors as the Acropolis Museum), the fact that since the marbles have been in England since the early 19th century, they have now become part of British cultural heritage, the potential for setting a precedent that could empty all the world’s museums where antiquities from other countries are kept.

In recent years, demands for the return of the marbles to Greece have become increasingly insistent, resulting in friction between Greece and the United Kingdom. An initial clash occurred between 2013 and 2015, when, following a meeting in July 2013 between the then Greek minister of culture and sports, Panos Panagiotopoulos, and the then director-general of UNESCO, Irina Bokova, Greece asked UNESCO to push the UK to participate in a mediation process in order to resolve the issue of the Parthenon marbles. Unesco sent an official letter to the U.K. Secretary of State, the Secretary for Culture, and the Director of the British Museum, requesting that the U.K. facilitate mediation with Greece. The British government and the British Museum responded only, separately in March 2015, rejecting the hypothesis (the British has always stressed the legitimacy of acquiring the sculptures). The Greek minister in turn responded that the UK showed little willingness to cooperate and dialogue, and ignored UNESCO’s recommendations.

The demands intensified starting in late 2018, in the wake of the great international debate on cultural decolonization and the restitutions that several countries have begun to undertake to their countries of origin. In January 2019, the director of the British Museum, Hartwig Fischer, declared in an interview with the Greek newspaper Ta Nea that the museum would not return the sculptures, arguing that the removal itself represented “a creative act,” that the British Museum also gives the sculptures a “specific context,” that removal is part of the history of the marbles, and that “even at the Acropolis Museum there are works that are no longer in their original context.” A few days later, the Greek Minister of Culture, Myrsini Zorba, responded by stating that Fischer’s words “degrade cultural heritage by turning it from a priceless universal asset to a mere bargaining chip,” that “they are reminiscent of colonialism,” and that they “ignore the international debate and the Unesco declarations, especially those concerning mutilated monuments, which deserve to be reunited and restored according to the fundamental principle of integrity, as required by the 1972 Unesco Convention.”

There was also no shortage of speculation about a temporary loan of the marbles to Greece: the British Museum, in this case, responded by arguing that a loan there can only be if Greece acknowledges that the sculptures are legitimate British property. A precondition obviously rejected by Greece. The matter was discussed, in the fall of 2021, at a summit between the two prime ministers of the United Kingdom and Greece, Boris Johnson and Kyriakos Mitsotakis, but the outcome was a cold shower for the Hellenes, since Johnson reiterated the British government’s position that the matter is the responsibility of the British Museum. And the museum, as it turned out, has no intention of returning the works.

An important breakthrough also came in the fall of 2021, when for the first time UNESCO adopted a Decision on the Parthenon Marbles, which came after the 22nd session of theUnesco Intergovernmental Commission for the Promotion of the Restitution of Cultural Property to Countries of Origin (ICPRCP), held between September 27 and 29. In the Decision, #22.COM 17, reads: “The Commission, 1) Recalling Article 4 paragraphs 1 and 2 of its Statute, 2) Noting that the request for the return of the Parthenon sculptures has been on its Agenda since 1984, 3) Recalling its sixteen recommendations on the matter, 4) Recalling also that the Parthenon is an emblematic monument of outstanding universal value inscribed on the World Heritage List, 5) Mindful of Greece’s legitimate and just request, 6) Recognizing that Greece requested the United Kingdom in 2013 to mediate in accordance with the Unesco Procedural Rules on Mediation and Conciliation, 7) Recognizing that the case has an intergovernmental character and that, therefore, the commitment to return the Parthenon sculptures falls on the government of the United Kingdom, 8) Expresses its deep concern that the matter is still on hold, 9) Further expresses its disappointment that its recommendations have not been observed by the United Kingdom, 10) Expresses its strong conviction that states involved in restitution cases brought to the attention of theICPRCP should make use of theUnesco Mediation and Conciliation procedures with a view to their resolution, 11) Calls on the UK to reconsider its position and proceed in a good faith dialogue with Greece on the matter.” This is the first UNESCO Decision to call on the British to reconsider their positions. The Decision, enthusiastically welcomed by the Greeks, could perhaps stir things up, although the British Museum stated shortly afterwards that it did not believe the case could be resolved by going through Unesco, since the museum is not a governmental body. But the issue is increasingly debated and it is not certain that sooner or later a change of direction will not come.

Essential bibliography

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.