“He made the plan and model and then began to have walled up the church of San Marcello de’ frati de’ Servi, a certainly beautiful work.” the church mentioned by Giorgio Vasari in his Lives is that of San Marcello al Corso, formerly known as San Marcello in Via Lata, the splendid building located in the final stretch of Via del Corso, almost arriving in Piazza Venezia, and the author is the Florentine architect Jacopo Sansovino (Jacopo Tatti; Florence, 1486 - Venice, 1570), who in 1519 was in charge of its reconstruction, which then continued for a long time due to various vicissitudes (the sack of Rome that drove Sansovino away from the city, a flood, various delays), so that only in the late seventeenth century could the church be completed with the facade designed by Carlo Fontana (Rancate, 1638 - Rome, 1714). The previous building, which had a different orientation (the facade was on the opposite side from the present one), had been destroyed on the night of May 22-23, 1519: tradition has it that the only artifact to survive from the fire was a wooden crucifix that decorated the high altar.

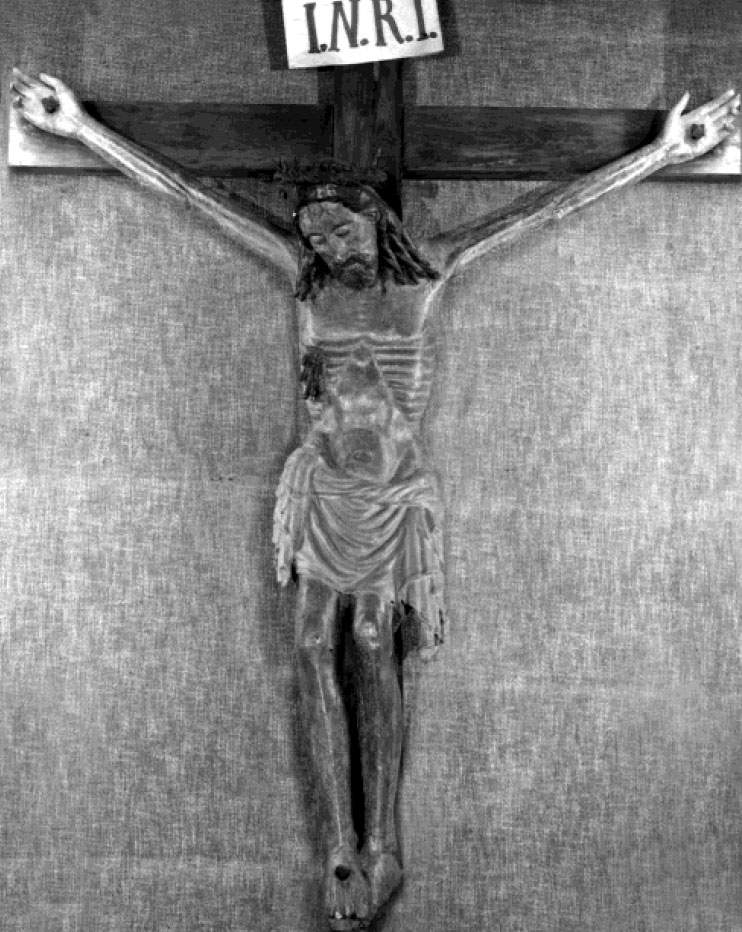

It is a work from the late 14th century, of which, however, we do not know the author: at the time, Rome recorded a conspicuous presence of similar artifacts, works often considered thaumaturgical and for this reason the object of constant devotion, especially in the age of the Counter-Reformation, when the Church had to restore a faith that was faltering under the wave of the Protestant Reformation. The crucifix in San Marcello al Corso, placed by scholars (most recently art historian Claudia D’Alberto) in the 1470s, is embedded in a dense network of cross-references to similar works found in Roman churches and dating to the same period: ours, for example, is placed in a relationship of dependence with the older crucifix in the church of San Lorenzo in Damaso, from which it takes its structure with the upper part of the body forming a triangle, the very strong patheticism of the suffering face, and the highly marked ribs and pectorals. There is a distance of about fifty years between the two works (that of San Lorenzo in Damaso would date from the first decade of the fourteenth century), and consequently the work of San Marcello al corso is stylistically more up-to-date, but the matrix is common: the model, specifically, would seem to come from northern Europe, a circumstance held in high regard at the time since the crucifix of San Lorenzo in Damaso would seem to be connected to the cult of St. Bridget of Sweden. The patron saint of the Scandinavian state, who lived between 1303 and 1373, spent the last part of her existence in Rome, and from her writings (in particular from the Sermo Angelicus) it would appear that she was a devotee of the crucifix of San Lorenzo in Damaso: it is therefore easy to imagine how artists lavished themselves on numerous reproductions of the archetypal image, and the crucifix of San Marcello al Corso itself is proof of this.

|

| Roman artist, Crucifix of San Marc ello al Corso (c. 1370-1379; polychrome wood; Rome, San Marcello al Corso) |

|

| German artist, Crucifix of Lorenzo in Damaso (c. 1300-1325; polychrome wood; Rome, San Lorenzo in Damaso) |

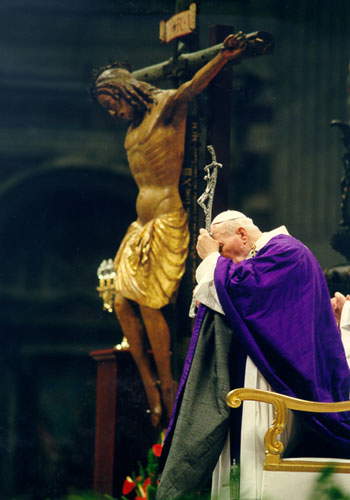

In any case, the crucifix, which escaped unharmed from the flames that destroyed the church of San Marcello al Corso in 1519, was immediately considered miraculous by the population, and this luminous reputation of his grew when, in August 1522, Spanish Cardinal Raimondo Vich, bishop of Valencia and Barcelona, wanted to bring the crucifix in procession throughout the city to ward off a plague that had broken out in Rome. The rite lasted eighteen days and ended with the entry of the crucifix from San Marcello in Corso into St. Peter’s Basilica.In the meantime, the epidemic had slowed down, and this event contributed to the crucifix’s name, which then became the protagonist of further processions, because the custom of carrying the crucifix from San Marcello to the Corso on the occasion of holy years or special events has been maintained ever since. The procession of the crucifix of San Marcello is thus attested during several jubilees: in 1675, the scenic apparatus set up around the procession was taken care of by Carlo Fontana himself, a further procession was organized for the extraordinary jubilee of 1933-1934, and the crucifix was still at the center of religious events for the jubilee of 2000, when it was brought to St. Peter’s and was embraced by John Paul II on the occasion of the Day of Forgiveness. The events then take us to March 27, 2020, when the crucifix still makes the journey from San Marcello al Corso to St. Peter’s, but without a procession because of the containment measures put in place to counter the Covid-19 coronavirus pandemic that has swept the world: on this occasion, Pope Francis has the crucifix placed in front of the entrance to St. Peter’s Basilica to invoke God’s grace against the spread of the pandemic.

Returning to ancient history, the 1522 event prompted a group of the faithful, led by some Roman nobles, to found that same year a confraternity, the Compagnia dei disciplinati, whose statutes were approved by Pope Clement VII in 1526 and confirmed by Julius III in 1550. The confratelli obtained the jus patronage of the fourth chapel on the right of the new church of San Marcello al Corso: this is the room that, to this day, houses the 14th-century crucifix. One of the confreres’ first measures was to adorn the chapel with frescoes, and to do so they decided to turn to one of the most important painters of the time, Perin del Vaga (Piero di Giovanni Bonaccorsi; Florence, 1501 - Rome, 1547). Giorgio Vasari again recounts the story in Lives: “Because of the praise given him in the first work done in San Marcello, it was resolved by the prior of that convent and by certain heads of the Compagnia del Crocifisso, which has a chapel there built by its men to gather there, that she should be painted; and so they allotted this work to Perin, with the hope of having some excellent thing of his own.”

|

| Pope Francis prays before the crucifix in San Marcello al Corso (2020) |

|

| Pope Francis in front of the crucifix in San Marcello al Corso carried to the entrance of St. Peter’s Basilica (2020) |

|

| Pope John Paul II with the crucifix of San Marcello al Corso in St. Peter’s basilica during the Jubilee of 2000 |

|

| The crucifix in front of San Marcello al Corso at the beginning of the jubilee procession in 1934, in an Istituto Luce film |

Perin del Vaga decorated the chapel presumably between 1525 and 1527 before leaving the city, also for the sack of Rome, so much so that it was Daniele da Volterra (Daniele Ricciardelli; Volterra, 1509 - Rome, 1566) who later finished the frescoes, and perhaps the original design underwent changes, because today only the vault of the chapel is decorated, while the rest of the room is unadorned. In addition, a ruinous restoration in 1866 caused the loss of some of the figures that decorated the vault: in particular, we no longer see the angels with the instruments of the Passion and the ignudi arranged on the arch frames (replaced by modern stucco decorations). Perino painted, in the center of the vault, the scene of the Creation of Eve, while on the sides the evangelists: he executed independently the figures of Mark and John, while those of Matthew and Luke were completed by the painter from Volterra. It is Vasari again who clearly describes these works: “he made in the half-barrel vault, in the middle, an istoria quando Dio, fatto Adamo, cava della costa sua Eva sua donna, in quale storia si vede Adamo ignudo, bellissimo et artifizioso, che oppresso dal sonno giace, mentre che Eva vivissima a man giunte si leva in piedi e riceve la benedizzione dal suo fattore: the figure of whom is made of the richest and gravest aspect, in majesty, upright, with many cloths around, which go round with the flaps the naked; and on one side with upright hands two Evangelists, of whom finished all the St. Mark et the St. John, except the head and one arm naked. He made for you in the middle between the one and the other, two cherubs who embrace for ornament a candlestick, which truly are of the most vivid flesh, and similarly the Evangelists very beautiful, in the heads and in the garments and arms and all that he made for them by his hand.”

If the Saints Mark and John are very ruined (infiltrations of moisture have severely damaged the paintings) and the others are partly marked by the intervention of Daniele da Volterra, who at the time of completion (between 1540 and 1543) was a little more than 30 years old helper of Perin del Vaga who, however, was also beginning to mature as an independent artist, the central panel with the Creation of Eve is one of the finest attestations of Perin del Vaga’s art, which bases its style on compositional simplicity, the use of strong iridescence, the monumentality of volumes that hark back to Michelangelo’s precedents (and this is also and especially true of the evangelists), and elaborate poses. The Creation of Eve is moreover a work that aroused the interest of a great art historian such as Giuseppe Fiocco, who in 1913, in one of his essays published in the Bollettino d’arte, after reconstructing the work’s history, first criticized the figure of the Eternal Father, “with a beautiful head freely inspired by Buonarroti’s Moses, but ”who has as if drowned the body in the many wrappings of the cloths,“ and the ”bodacious Eve, though lively in movement,“ and then unreservedly praised ”the artificial nude of the Adam, less slavishly cast over his terrible model, and most successful in the abandonment of sleep and the elegant proportion of the body." A nude that will not be difficult to trace, given the pose, to Michelangelo’s River God now owned by the Accademia delle Arti del Disegno. Fiocco then emphasized Raphaelesque references, particularly in the putti that animate the panels with the evangelists and recall the Raphael of the frescoes in Santa Maria della Pace.

|

| The facade of the church of San Marcello al Corso. Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Perin del Vaga, The Creation of Eve (1525-1527; fresco; Rome, San Marcello al Corso). Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Perin del Vaga, Saints Mark and John (1525-1527; fresco; Rome, San Marcello al Corso). Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Perin del Vaga and Daniale da Volterra, Saints Matthew and Luke (1540-1543; fresco; Rome, San Marcello al Corso) |

However, these are not the only works of art that accompany the story of the crucifix at San Marcello al Corso: there are in fact paintings that even tell the story of the crucifix. In 1564, the Compagnia dei disciplinati was elevated to the rank of archconfraternity and consequently increased the number of members, so that the sodality needed to provide itself with a new headquarters, a place of worship larger than the chapel in the church of San Marcello al Corso: already a few years earlier, in 1556, two members of the confraternity, Cencio Frangipani and Tommaso de’ Cavalieri (Rome, 1509 - 1587), the latter known for his great friendship with Michelangelo, identified the possible site (a piece of land occupied by two stables, not far from the church of San Marcello al Corso) on which theOratory of the Crucifix would be built. The first stone was solemnly laid by Cardinal Ranuccio Farnese (a plaque recalls that the building site was able to start thanks to the resources offered by him and his brother Alessandro) on May 3, 1562, and the construction of the oratory was finished as early as the following year: however, the work was completed in 1568 when the façade was erected, based on the design of the young architect Giacomo della Porta (Porlezza, 1532 - Rome, 1602), who was responsible for the entire building (he was only 30 years old when he provided the design of the oratory to the confraternity). The following years saw a succession of artistic interventions: the wooden lacunar ceiling was finished between 1573 and 1574 (it would later be replaced in 1879), and between 1578 and 1583 the frescoes of the side walls were proceeded with, which were to tell the Stories of the Cross, to which some of the greatest painters of the time, under the supervision of Tommaso de’ Cavalieri himself and the painter Girolamo Muziano (Acquafredda, 1532 - Rome, 1592), attended, namely Giovanni de’ Vecchi (Borgo Sansepolcro, c. 1536 - Rome, 1614), to whom we owe the development of the general scheme, Niccolò Circignani known as il Pomarancio (Pomarance, c. 1530 - after 1597), Cesare Nebbia (Orvieto, 1536 - 1614), the other Pomarancio, namely Cristoforo Roncalli (Pomarance, c. 1553 - 1626), Baldassarre Croce (Bologna, 1558 - Rome, 1628) and Paris Nogari (Rome, c. 1536 - 1601). De’ Vecchi was Alessandro Farnese’s favorite painter, Nebbia was the best of Muziano’s pupils, Circignani had worked with all the other three, while Croce, Nogari and Roncalli were “recruited” from the site of the Vatican’s Gallerie delle Carte Geografiche, where all three were active in the 1580s along with Circignani (it was in all likelihood he who recommended them to his colleagues).

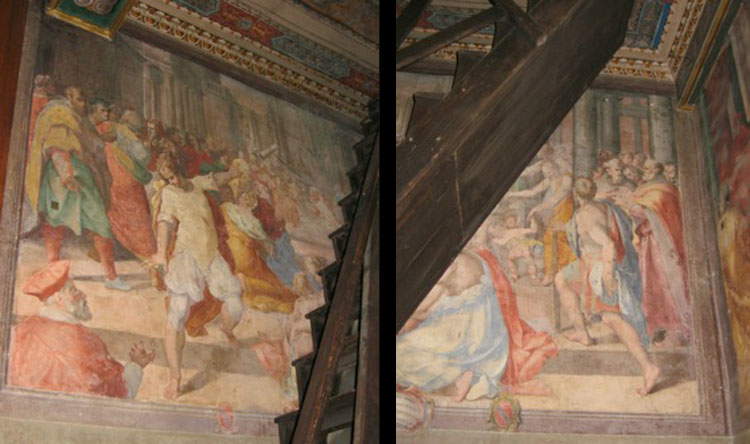

The counterfaçade, on the other hand, was entirely decorated with frescoes telling the stories of the confraternity, in which the vicissitudes of the miraculous crucifix of San Marcello al Corso are obviously included. In order of chronological reading of the narrated events, we have the crucifix of San Marcello surviving the church fire (by Cristoforo Roncalli), the procession of the crucifix in 1522 (by Paris Nogari), the approval of the statutes of the Compagnia dei disciplinati (by Baldassarre Croce), and the foundation of the convent of Capuchin nuns at the Quirinale (by Cristoforo Roncalli): the latter was erected in 1571 by the Compagnia dei disciplinati after receiving the area that would house the building as a gift from the noblewoman Giovanna d’Aragona Colonna, duchess of Tagliacozzo. The decoration of the entrance wall began in 1583, soon after the completion of the side walls (we assume this on the basis of the only payment that is preserved, relating to the scene of the foundation of the convent of the Capuchin nuns of the Quirinal): the frescoes were stylistically conducted in a very homogeneous manner, so much so that the scene with the approval of the statutes was in the past attributed to Nogari, but in 1963, during restoration work involving the entire oratory, the signature of Baldassarre Croce was discovered and it was therefore possible to trace the scene back to the Bolognese. Typical examples of the Roman manner, the frescoes of the Oratory of the Crucifix are distinguished by their great ease of reading, the presence of a few figures endowed with important proportions, and the breadth of the volumes (see the figures in the foreground of the procession scene). On the scenes, those of Cristoforo Roncalli stand out, which differ from those of Croce (the latter, moreover, rather ruined) and from the episode depicted by Nogari in terms of greater formal precision, less stereotyped figures, and more powerful language (see the figure in the foreground of the fire scene).

|

| The Oratory of the Most Holy Crucifix |

|

| The interior of the oratory of the Santissimo Crocifisso |

|

|

| Paris Nogari, The procession of 1522 (1583-1584; fresco; Rome, Oratory of the Crucifix) |

The Oratory continued to undergo remodeling over the following centuries, beginning with the high altar, rearranged in 1740 to better accommodate the 16th-century crucifix, inspired by the one in San Marcello al Corso, donated by a faithful in 1561. Several restorations followed in the nineteenth century, since the little church was damaged during the Napoleonic occupation, while between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries the loss of worshippers and the reduced activity of the confraternity threw the oratory into oblivion: only in 1963, when the building was entrusted to the care of the Sisters of Bethany, was it revived with a restoration directed by Arnolfo Crucianelli, and further interventions were conducted in 1989 and 2000, the latter on the occasion of that year’s jubilee, with the restoration of the facade. Today, the Oratory of the Crucifix is home to theRoman Musical Oratory, which continues the centuries-old tradition of sacred music concerts that have always been held inside the building since the 16th century.

As for the crucifix of San Marcello al Corso, the work continues to be an object of strong veneration. And keeping the cult of the miraculous work alive today is theArchconfraternity of the Most Holy Crucifix in Urbe, heir to the Compagnia dei disciplinati, and active in the building of worship on Via del Corso, which continues to welcome thousands of faithful and devotees who flock to pray before this sculpture. As it has for the past five hundred years.

Reference bibliography

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.