“Alice was dying of boredom [...], she had peeked a few times at the book her sister was reading, but there were no figures or dialogue.” Yayoi Kusama was also bored to death as a child, forced to read a life not her own through lenses tarnished by oppressive family teachings and upbringing, steeped in heavy socio-cultural taboos, antiquated traditional values, and Eastern patriarchal legacies. Education, taboos, backwardness: an explosive fuse that, more often than not, deflagrates into “insane” existences spent amid episodes of hysteria, hallucinations and psychic disorders. Such cases, especially for women, harassed for millennia by cramped living conditions, have dark and ominous or, at best, annihilating outcomes. But the unexpected is just around the corner and, as in the best fairy tales, can turn into something real. Because sometimes, it is precisely imagination, art and creativity that take over, acting as escape routes, or rather, in the words of Lewis Carroll, manage to catapult us down the “rabbit hole,” allowing extraordinary things to happen. The story of Yayoi Kusama is one such case.

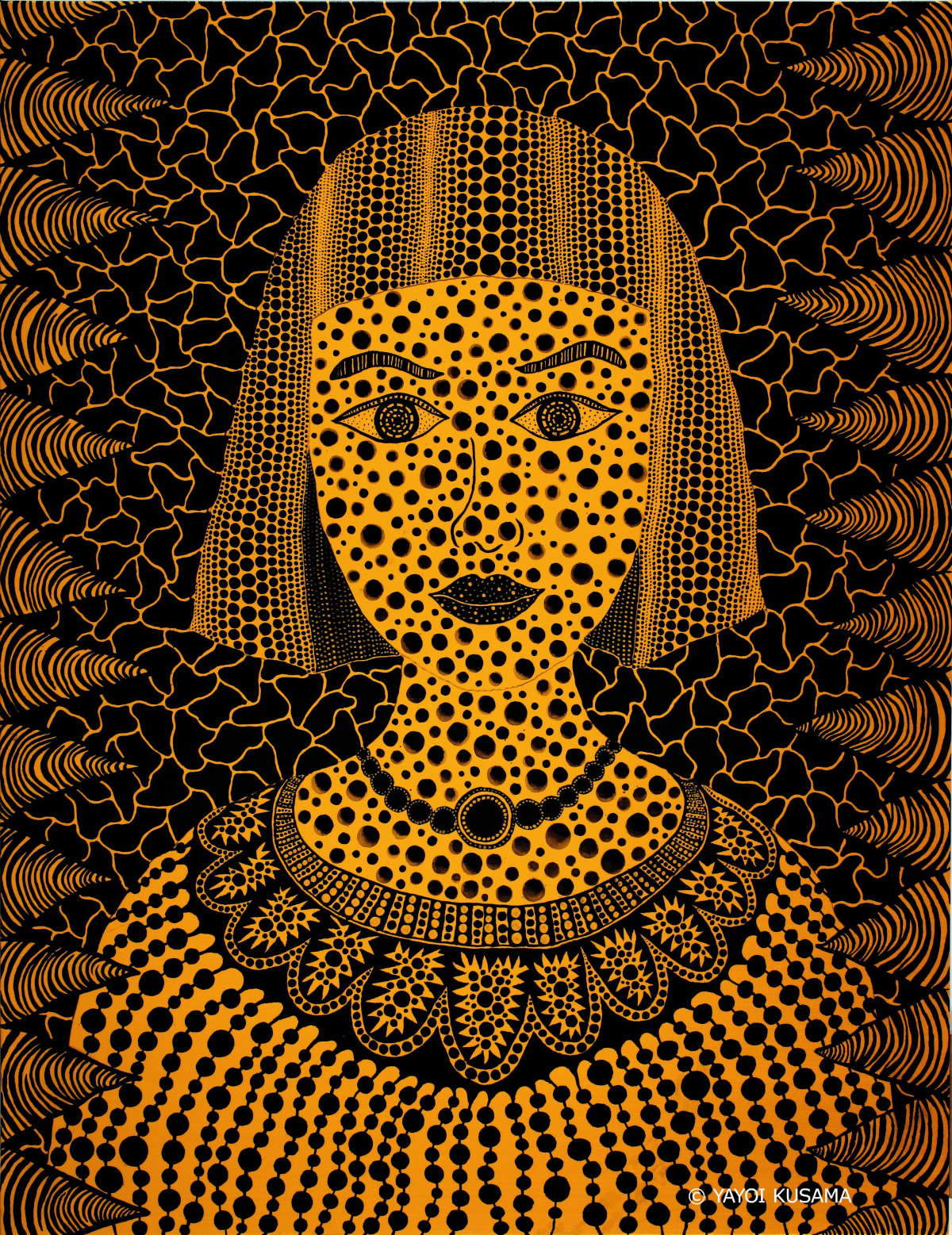

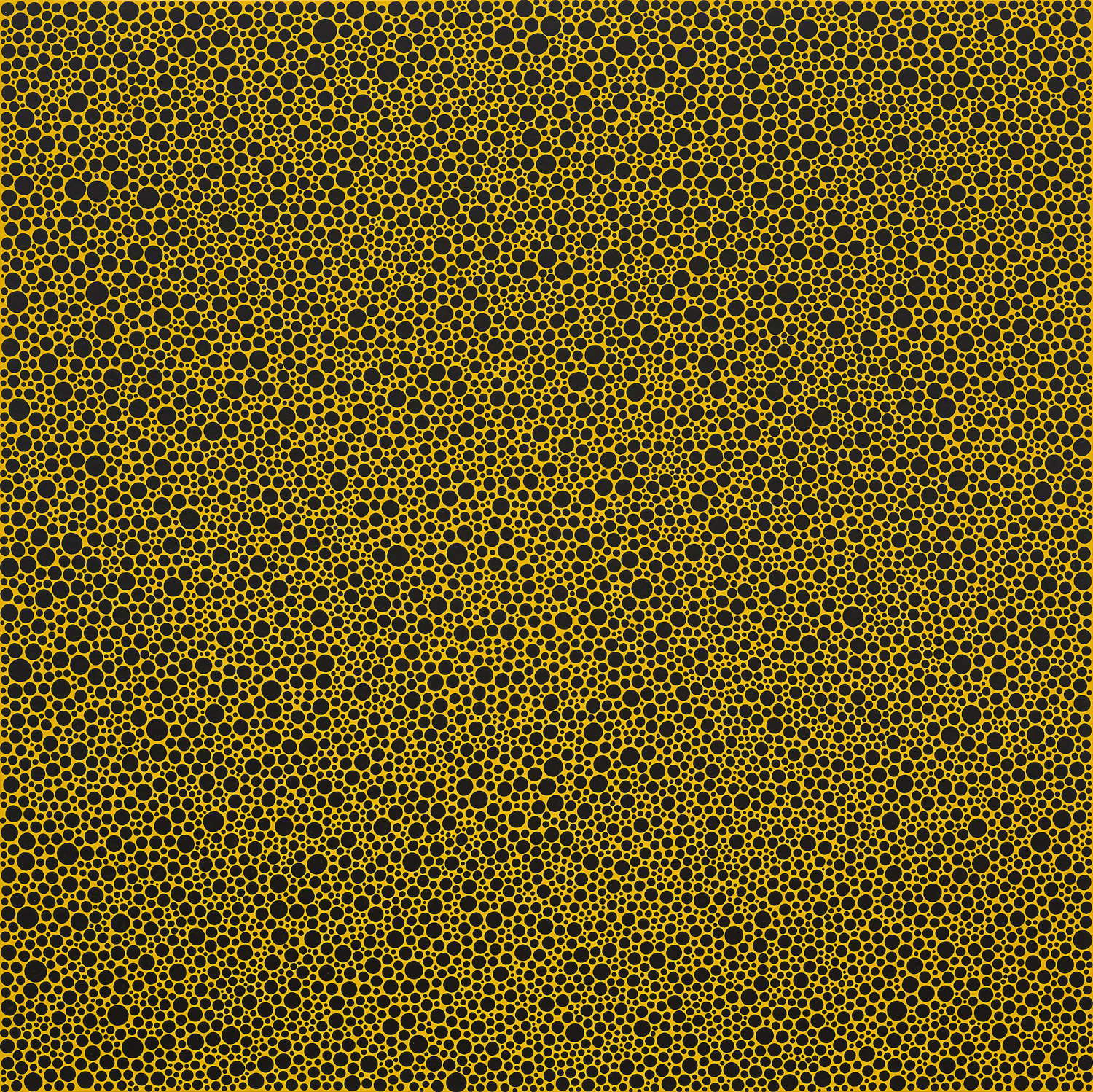

A little girl who looked at the world with different eyes, all her own, where even the laws of nature are suspended; and so, shrinking or enlarging herself, in the shape of polka dots or with giant, colorful pumpkins, this wonderful inner country she recreated it through hypnotic, powerful and magnetic works, inclusive, these yes, of figures, symbols, flowers, words and phalluses, all elements that the taboos she had suffered had at first driven back.

Born in 1929 in Japan, drawing polka dots precisely, quick elements to wrest from family control, she soon realized how artistic expression was a cathartic tool that could transform her life from stifling to free self-expression. In her hometown of Matsumoto, where a place, unrelated to her, was reserved for her in the seed planting of the family estate and where, just as she was strolling through one of the flower fields, a dazzling light caused her first hallucinations, a fortuitous “stumble”, as in the best fairy tales, changes her perspective by totally reversing her situation: reading a book featuring the paintings of Georgia O’Keeffe, wife of photographer Alfred Stieglitz. Everything flows at lightning speed, Kusama contacts her and finds an answer.

From this moment on she “sinks” down, just like Alice, into Wonderland, while still continuing to this day to live in an asylum. It is the beginning of a fabulous, parallel world and a dazzling career, until just before opposed by her family, which destroys her early work.

Seattle, in fact, is the first stop, where in 1957 she exhibited at Zoe Dusanne’s gallery, then New York, the coveted destination, a city where, thanks to O’Keeffe’s referrals, she would meet art dealer Edith Halpert of the Downtown Gallery. Two years later, in 1959, in the halls of Brata Gallery he opened his first solo exhibition, Obsessional Mono chrome where his large monochrome canvases, Infinity Nets, were also presented. Then would come the walls of the famous Leo Castelli Galley and in 1963, the exhibition of the installation that would appeal to Andy Warhol, Aggregation: One Thousand Boats Show. And still other solo exhibitions-Driving Image Show in 1964, Infinity Mirror Room-Phalli’s Field in 1965, Love Forever in 1969, and on and on, up to the happening Anatomic Explosion, the illustrations of the latest edition (Fandango, 2013) of Alice in Wonderland, and finally the exhibition of the year, Infinity Present open from November 17, 2023 at the Palazzo della Ragione in Bergamo: an exhibition that has already driven the booking system “crazy” and forced the organizers, The Blank, to extend the opening hours, guaranteeing 10,000 more admissions.

Modern Alice (“the ancestor of the hippies,” as she calls herself), Yayoi Kusama, after years of great success experienced in the U.S. where she exhibited alongside the greatest of the time, minimalists and conceptual artists above all, such as Claes Oldenburg, Robert Morris and the Italian Piero Manzoni, returned to Japan and went to live, voluntarily, in a Tokyo asylum, since 1977. Here she will be forgotten for a while, until younger generations of artists recognize her work as inescapable and identify with it, especially as it is marked by the “connection between the personal and the formal, the organic and the mechanical, the physical and the intellectual given” (so Graham W. J. Beal, Director of the Los Angeles County Museum of art).

It is his comeback. New successes and exhibitions will crown the artist’s fame, with even the opening of a museum dedicated to her. New generations but not only that, new trends, studiesî, interpretations and attention to the female world also contribute to this ascent. Obliteration and semi-cancellation of the object, reduction to the degree zero of the sign, subversive exorcizing of the taboo of sex, small colored dots, that is, a pointillism that becomes “environmental” and physical (I am referring to the Body Painting Happenings, in which naked male and female bodies were thus painted), works with a spider’s web effect that we see again later in more monstrous and gigantic forms in the artist Louise Bourgeois, or again, the performance against the art market set up thanks to Lucio Fontana’s intervention as an “off-show” at the Biennale in 1966: reading the upside-down world correctly, the “soft and formless universe” (Fabriano Fabbri) of Yayoi Kusama is not an exercise in style, nor an easy task. And in modern criticism, her work unravels in a double vision, which on the one hand would reflect Bonito Oliva’s Transavantgarde process, i.e., that artistic context in which “every work presupposes an experimental dexterity, the artist’s surprise at a work, is constructed no longer according to the anticipated certainty of a project and ideology, but is formed before his eyes and under the impulse of a hand that sinks into the matter of art, in an imaginary made up of an embodiment between idea and sensibility,” while, on the other hand, he opens up to the aesthetic perspective formulated by Tosa Mitsuoki, according to whom his “principles are based on the relationship between perceptible reality and the projection of it in art. Art has the task of ’imitating nature’ but, at some point, the artist must depart from it and even distort it.”

The great, first and foremost public triumph of the latest exhibitions, however, raises at least one further question: is her artistic production really well understood, absorbed, or, as is often the case, is it her biography, extravagant, subversive, that dictates the law, intrigues and makes heady numbers even at auctions? For a long time Kusama risked (and still does) getting entangled in this controversial misunderstanding, a querelle that runs throughout art history, ancient and contemporary.

One certainty remains. Between adventure and method, to create like the Mad Hatter with one’s own life, however complex, and with one’s own work, however multifaceted, dystopian and misunderstood, a world unto itself, is not a common operation; it requires, instead, a capacity for fairy-tale invention that few know how to make their own and real.

All the more so if rewriting it all over again means turning traditions upside down, routing taboos, conditioning, and asserting, as Yayoi Kusama stubbornly did, with courage, beyond her illness, her own freedom, especially for a woman, and especially if she was born in a country like Japan in those years still imbued with a culture that sustained a backward and stifling system of values and traditions.

Just as the story of Alice Liddell, the little girl who inspired Carroll’s novel, tells us of a country like England that at that time imposed a childhood upbringing based on a “proper” entrance to the adult world, Yayoi Kusama’s story also tells us that overthrowing an order established by oppressive rules and an imposition of values that does not take into account the innermost essence of the child’s world and, in general, the nature of human beings, is possible. Alice in Wonderland and Yayoi Kusama’s fairy tale, out of all distortion, has this profound meaning: inventing an upside-down world can be done, because a more human and dreamy look is just around the corner. All you have to do is close your eyes.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.