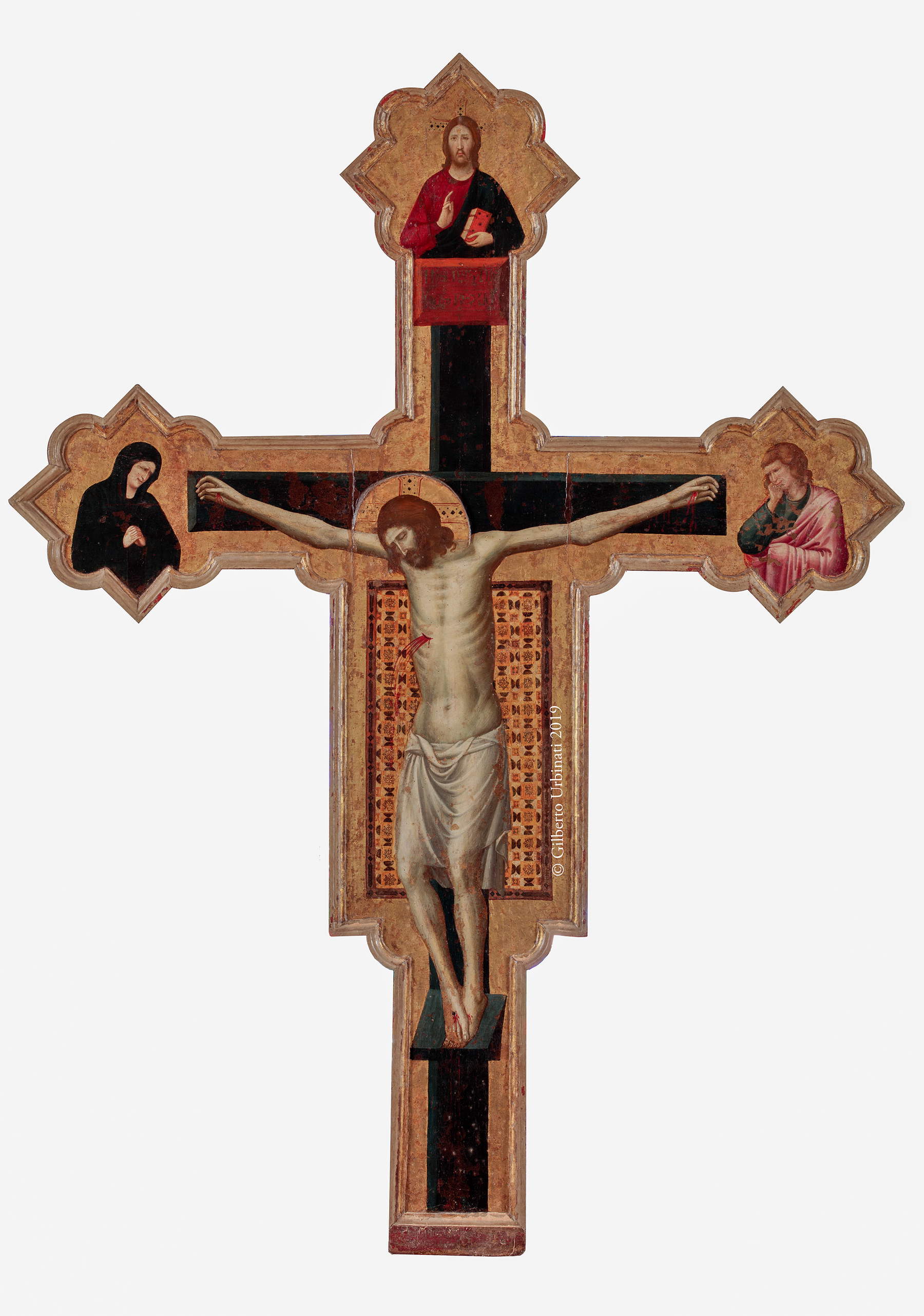

By the signature on its vertical arm alone, the painted cross preserved in the church of San Francesco in Mercatello sul Metauro, a village in the Marche Apennines halfway between Urbino and Sansepolcro, could be considered an exceptional work, because signed and dated works by Rimini Giottesque painters are rare, and the Mercatello cross is moreover the only work signed and dated by the artist who was the progenitor of the Rimini School, Giovanni da Rimini (documented from 1292 to 1309/1314): a circumstance that transforms the work, to use Alessandro Giovanardi’s expression, into the “cornerstone of an entire cultural-historical edifice.” The “Mercatello Cross” has recently been restored: the exhibition The Gold of John. The Restoration of the Cross of Mercatello (curated by Daniele Benati and Alessandro Giovanardi, in Rimini, at Palazzo Buonadrata, from September 18 to November 7, 2021), an extraordinary opportunity to see together several painted crosses produced in early fourteenth-century Rimini, has shed further light on this masterpiece, bringing the work back to Rimini eighty-six years after the last exhibition, which was held in 1935 and in which a first reconstruction of the events of the Rimini school was proposed. The inscription that appears on the plaque placed at the bottom of the work reads “JOH[ANN]ES PICTOR FECIT [HO]C OPUS / FRA[TRIS] TOBALDI MILL.O CCCVIII” (although the year has been read as “XIII” as well) and thus provides us with several pieces of information: the author (Giovanni), the year of completion (either 1309 or 1314: in either case it would be the least ancient work in the corpus of Giovanni da Rimini) and the commissioner (the otherwise unknown Friar Tobaldo, the Franciscan father who commissioned Giovanni to execute the cross for the order’s convent church at Mercatello).

The work was only made known in 1913, by Lionello Venturi who, believing he was reading the year 1344 in the date, thought it was executed by Giovanni Baronzio. At that time, the figure of the elusive Giovanni da Rimini was not yet known: only in 1965, the discovery by Carlo Volpe of documents dating back to 1292 that identified him as a different person than the already known Giovanni Baronzio, succeeded in demonstrating that at that date there already appeared to be active a “Johannes pictor” to whose hand could therefore be ascribed the work, which, because of its manner, was incompatible with an advanced dating such as the one read by Venturi, but which in any case had already been assigned to Giovanni da Rimini in 1937: the insight was due to Cesare Brandi, who that year compiled an initial core of Giovanni’s works, including the Mercatello Cross. In the same year, scholar Augusto Campana also solved the date problem, first noting that the inscription bore the year 1309 or at most 1314. The cross’s subsequent history has been somewhat troubled: in 1966 it was brought to Florence to be restored in the superintendence’s laboratories, but it fell victim to the November 4 flood (showing damage that is still visible on the pictorial surface), and only in 1971 was it returned to the Mercatello church. Recently, the photographer Gilberto Urbinati, having to document the cross for a photographic campaign, realized that it was suffering a ruinous attack by xylophagous insects: the need to repair the work from the damage caused by woodworms therefore entailed a new restoration, the one carried out by the company Ikuvium R.C. of Gubbio and directed by Tommaso Castaldi, the results of which are presented in the exhibition at Palazzo Buonadrata.

Already at the time of its rediscovery in 1913, the work was badly battered, with widespread color fading (especially on the gold background around Christ Pantocrator and the figures of the mourners) and with marks traceable to the action of rainwater on the face and bust of Christ. The work was in fact not on display in the church, but crammed into a woodshed, and had probably been there since the time of the Napoleonic suppressions of the monastic orders: after the discovery, it was restored by the Arezzo painter Gualtiero De Bacci Venuti (chosen by Venturi himself, then director of the Urbino Galleries) and repositioned in the church. “The Crucifix,” De Bacci Venuti reported in a 1926 article, “was broken down because of numerous scratches” and “for having been various times abandoned in a woodshed among logs and bundles and destined for fire.” Even during the 1935 exhibition, however, the work continued to look shabby, and its conservation vicissitudes were not helped by the events of World War II, during which the cross was taken by Pasquale Rotondi to the storage rooms of the Ducal Palace in Urbino, where it was still registered in 1948. Years later, in 1965, a campaign by the Soprintendenza delle Marche documented its critical state, and as anticipated the Mercatello Cross was taken to Florence for restoration.

The intervention was already finished and the work ready to return from the Marche when, on November 4, 1966, the flood of the Arno swept through the workshops in Via della Ninna, not far from the Uffizi: “its location a few steps from theArno and in a basement environment,” Castaldi writes in the 2021 exhibition catalog, “is sufficient to describe the force with which the waters of the river had to strike the works.” According to the report of Umberto Baldini, then director of the Restoration Cabinet of the Superintendency of the Galleries of Florence, the cross of John lost 15 percent of the pictorial surface, although, fortunately, the losses were not concentrated in a single point, but were small and widespread. The work was therefore hospitalized in the Limonaia of Palazzo Pitti until October 1967 (i.e., for as long as it took to dry), after which it was assigned to the Palazzo Pitti restoration laboratories: the delicate intervention lasted, as mentioned above, until 1971, and the Mercatello Cross in 1973 was ready for a new exhibition, held at the Palazzo Ducale in Urbino and in which some recently restored works were displayed.

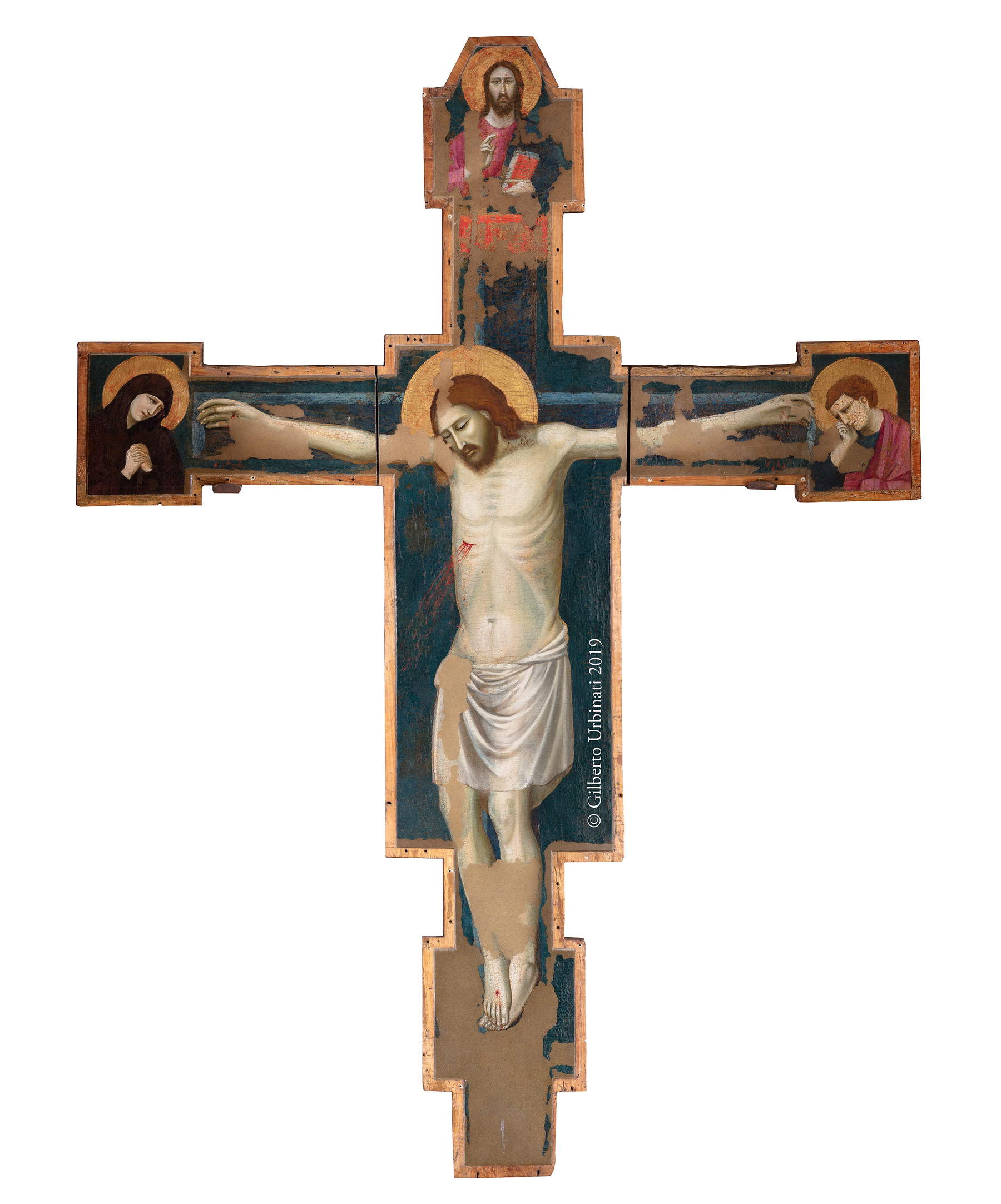

Exactly fifty years have therefore passed since the last restoration, and there are many new features of the one in 2021: to give an idea of how demanding the work was, suffice it to say that the removal of the cross from the apse of the church of San Francesco alone took a whole day and nine people. And the restoration itself was long and painstaking. For the first time, a thorough campaign of diagnostic investigations was conducted( multispectralimaging, X-fluorescence, optical microscopy, recognition of the wooden essence, namely maple wood for the table and cypress wood for the crossbeams), which made it possible to detect the repainting conducted following the flood, to discover the preparatory drawing done in charcoal (“from the effects of surprising softness.” writes Castaldi, “well detectable in the hair and tunic of St. John, in the book of the Blessing Eternal and in the details of Mary’s praying face and hands”), to understand what kind of pigments the painter had used (cinnabar for the red parts, azurite for the blue, use of white lead to obtain brighter effects and vice versa of earth to have darker tones, copper green, all on a plaster preparation). Once the diagnostic campaign was finished, the restorers carried out the biological restoration of the panel by subjecting the wood to biocidal intervention to eliminate woodworms (a double intervention of this type was necessary, since after the first one the insects had returned), and then proceeded with the removal of the protective varnish, which had yellowed (this last operation allowed the recovery of the legibility of the chromes used by Giovanni). The pictorial additions (“although they were of good quality,” Castaldi says) made during the post-flood restoration were then removed, and this was because they gave an effect of disharmony. “In keeping with the skillful previous restoration,” Castaldi further explains, “the intervention just completed was guided by the objective of rebalancing the additions to neutral with each other and in their relationship with the original pictorial surfaces, in order to harmonize the visual impact of the work, which was still marked by abrupt dissonant areas.” The gaps were therefore restored in the smaller areas, while for the larger areas, since these gaps “were now sedimented in the collective image of the work,” the restorers opted to respect the conservation history, which was therefore not concealed: “the blemishes still present on the pictorial surface or the chromatic falls,” explained the director of restoration, “are in fact the result of the damage inflicted on the Cross by time and events.” Finally, last operations, the completion of the wooden frame with stucco inserts in the missing parts, the integration of the gilding and the rebalancing with the neutral-treated areas. The back of the work (formerly protected with a layer of red ochre) was also meticulously investigated. Unfortunately, it was not possible to shed light on the date given in the inscription: the flood damage was too heavy to resolve the question of the year of execution of the cross.

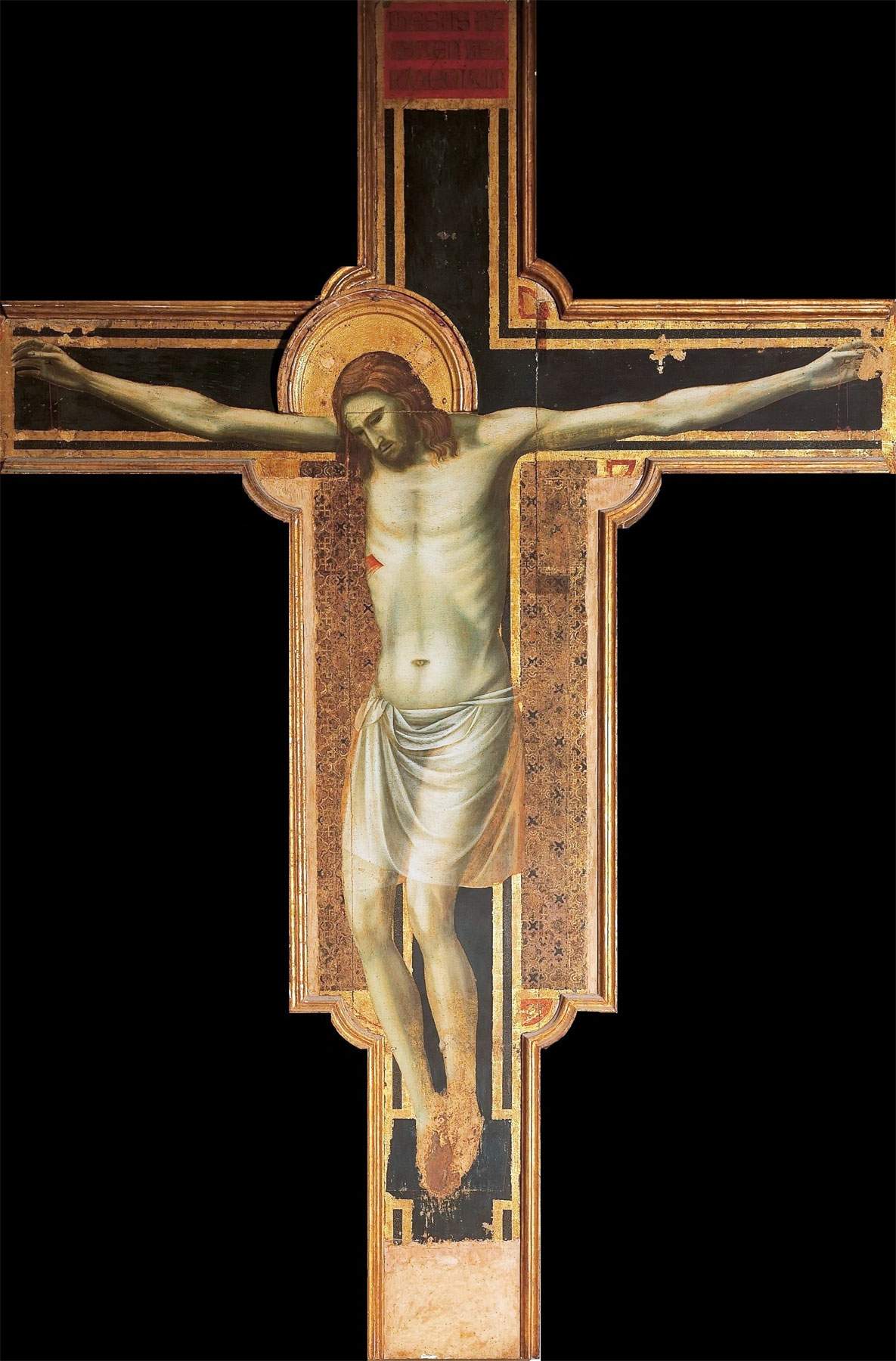

What is the importance of the Mercatello Cross in the context of studies on the 14th-century Riminese School? It is explained by Daniele Benati: it is in fact thanks to this work "that we are able to restore a name to one of the highest protagonists not only of that event, but of the entire Italian Gothic: an artist for whom the very qualification of ’Giottesque’ seems reductive, since, putting the accent on his albeit enthusiastic adherence to Giotto’s new language, it leaves in the shade the motives that must have presided over the early formation of a painter whom we are obliged to believe was active at least from the late 1380s onward." It is in fact from the Marche cross that we derive the artist’s name, and it is also a work that allows us to better understand the evolution of his language. It is in fact the last work in chronological order among those that can be assigned to Giovanni da Rimini (if we make an exception for the Talamello cross, of uncertain dating), and it is not his first painted cross. The oldest of those known is the Diotallevi Cross, so known from the name of the collection where it was located before Marquis Adauto Diotallevi donated it to the City of Rimini (today it is part of the City Museum). Like the Mercatello Cross, it belongs to the Christus patiens typology, with the suffering Christ on the cross, and like the Marches panel has at the ends of the horizontal arm the figures of the mourners, the Virgin and St. John, and on the cymatium the figure of the Pantocrator. The Diotallevi Cross is dependent on Giotto’s cross preserved in the Malatesta Temple, but at the same time it does not lose its connection with the Byzantine tradition (and it is because of such relationships that it is considered earlier than the Mercatello Cross), and it reveals a certain closeness to the frescoes in the church of Sant’Agostino in Rimini: “The diaphanous beauty of Christ’s tapering body, untouched by shadows,” Benati writes about the Diotallevi Cross, “is in fact found in the figures that populate the walls of the chapel of the Virgin, as if enclosed in a luminescent cocoon, while to choices of Byzantine matrix, destined to be later set aside, refers the triple embroidery of the loincloth on the belt, which alludes to the cingulum of thirteenth-century crosses.” In the Diotallevi Cross, then, Giovanni da Rimini uses for the background the same decorative scheme employed by Giotto in the cross of the Malatesta Temple, and like Giotto he decided to place the figures in a mixtilinear frame instead of the traditional rectangular layout of the crosses of Cimabue and Giunta Pisano: although the figures in Giotto’s cross are no longer together with the rest of the work (the cymatium with the Redeemer in particular is in a private collection in London), his work was, to our knowledge, the first to introduce this innovation, to which Giovanni immediately adhered.

Preceding the Mercatello Cross is a further painted cross by Giovanni da Rimini, owned by the Moretti Gallery in London, which, unlike Giovanni’s other known crosses, turns out to have been heavily curtailed: we are left with only the figure of the Crucified One nailed to his cross, lacking the mourners and the background. This work, purchased in 2007 by Fabrizio Moretti in an auction at Christie’s (the work in the past has had tormented travails: it belonged in fact to the collection of the Jewish merchant Jacques Goudstikker, from whom the collection was taken by the Nazis, only to be returned to the family in 2006 and put up for sale soon after) had previously been assigned to Baronzio: later traced back more correctly to Giovanni, it differs from the Diotallevi Cross in a more natural rendering of Christ’s body, where, Benati explains, the side and belly are “described with a very fine, opalescent brushstroke,” while the loincloth is no longer rolled up like that of the cross preserved in the Museum of the City of Rimini, but more delicately wraps around Christ’s hips as is the case in Giotto’s cross.

The Mercatello Cross comes at the apex of a path during which Giovanni da Rimini increasingly freed himself from his dependence on the Byzantine modes that, writes the art historian, “must have animated his thirteenth-century activity, unfortunately unknown to us, in favor of an increasingly convinced adherence to Giotto’s new language.” These are cues that are not lost in his works: “indeed,” Benati continues, “his never interrupted link with this older oriental substratum to give substance to his progressive choice of field. That is, it is his early convictions that provided him with a yardstick by which to assess the scope of the language he was gradually embracing; and it is in this ability to weigh the various options open to him by coeval painting and to choose with reason the one that appeared most convincing to him that Giovanni’s greatness ultimately lies” compared to the Giottismo of another great artist of the local Giottesque school, Giuliano da Rimini, a Giottismo that scholar Giovanna Ragionieri has described as “enthusiastic and somewhat uncritical.” The Mercatello Cross is an example of how his adherence is, on the contrary, “painfully critical,” Benati points out. It is a work of great naturalism, but also of great refinement (see, for example, the drapery of Christ’s loincloth, the decoration of the cloth on the background, the face of Christ where one notices a “brushstroke of a still neo-Hellenistic taste” but not for that reason incapable of restoring the naturalness of Jesus’ profile, and then again the gesture of John holding his fist covered under his cloak as a sign of mourning), is the most monumental of Giovanni da Rimini’s painted crosses, capable of declining Giottesque naturalism into a more dramatic style but without renouncing the delineation of an image of supreme elegance. The Rimini exhibition then underscored the need to study a fourth cross, that of the church of San Lorenzo in Talamello, first attributed to Giovanni in 1965 by Carlo Volpe. In fact, the complete authorship of this work, which is poorer than the others (due to its Augustinian commission, on the basis of which its more archaic appearance, complete with rectangular boards at the ends, can also be justified: the volumetries of the body of the crucifix, however, reveal a late realization, so much so that it is thought to date it to after the Mercatello Cross), and which presents some features that have suggested the presence of a collaborator.

The iconography of the Mercatello Cross, investigated by Alessandro Giovanardi, who in the catalog of the Palazzo Buonadrata exhibition returns an accurate study of the figures that appear in this and other crosses by Giovanni, does not differ from that of the other painted crosses that, the scholar writes, “participate in the symbolic role of separation-conjunction proper to the tent of the Temple , and are therefore employed in the veiling-disclosing operation of the Eucharistic mystery, celebrated by the priests on the altars, to which they introduce or on which they loom vertically, summarizing in their own iconographic structure the cosmic sense of the bloody sacrifice of the man-God of which the sacrament is a real and bloodless re-proposition.” On the top appears the blessing Christ, with his three fingers (thumb, little finger and ring finger) gathered to symbolize the Trinity, the purple tunic alluding at once to his kingship and his human nature (red is the color of blood), while the blue cloak is on the contrary a reference to his divine dimension (the color of heaven). The book, on the other hand, is symbolic of the Divine Law, and is closed since only he is allowed to open it. Shifting the eye downward, Christ suffering on the cross, writes Giovanardi, is "a direct child of Byzantine iconography, coming from the sequence of the paschal mystery, with all its sacramental and mystagogic implications; an initiatory path of the gaze and intelligence that John, with the co-presence of the Patiens and the blessing Pantokrator, does not seem to have lost.“ On the sides, finally, the Virgin and St. John, dismayed, at the same time invite the viewer to participate in the sorrowful scene, and being woman and man ”also represent the two opposite poles of the cosmos, the totality of the earthly horizon, to which the sacrifice of the Cross is addressed." As is the case in many crucifixes, blood runs down the vertical arm and bathes the ground of Golgotha, where according to medieval legend Adam was buried: this is an allusion to Christ’s descent into Limbo, from where the Savior would return to take to Paradise the righteous who had disappeared before his coming, but it is also a reference to the idea of Christ as the new Adam.

Finally, it is interesting to understand where the cross was originally located inside the Mercatello church, a subject that scholar Fabio Massaccesi addressed at the Rimini exhibition. In 1840 the church, after a period spent in the chapel of the Crucifix, it was hung on the counter-façade, while in 1910 it was placed, Massaccesi writes, “on the closure of the new back-chorus, which was accessed by two curtained openings, next to the high altar,” and placed in axis with the polyptych by Giovanni Baronzio that was on the altar mensa. Originally, however, it must have been placed on a beam (as we see it today) arranged at the entrance to the apse, in a location, Massaccesi writes, “connected to the presence or absence from the origin of the choir in the main chapel,” and from which the partitioning that instead characterized other Franciscan buildings of worship was perhaps absent. In a triumphal position therefore, in front of the eyes of all the faithful: “in an axial dynamic,” Massaccesi writes, "prospectively the cross became increasingly coincident with the high altar (placed, however, in the sanctuary proper) and liturgically served to emphasize the renewal of the Eucharistic sacrifices on those tables on which the Time of salvation was scanned, tripartite: ’ante legem,’ ’sub lege,’ and ’sub gratia.’" Reconstructing these relationships, contexts and their origins, at a time when many works (especially medieval) are decontextualized, is one of the most interesting and exciting aspects of art history. The Mercatello Cross, not enough of the many reasons why it is a work of supreme interest, also offers this possibility.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.