The total project. A brief history of the dialogue between art and design

Talking about the relationships between artists and designer-designers is both easy and complex at the same time. There are many Italian and international examples, and now even in design history textbooks the paths and implications have begun to be delineated and explored. Our, all-Italian, idea that there is an art with a capital “a” and a type of cultural expression that from the project has as its goal only large-scale industrial production, is a moralistic and provincial attitude that has no counterpart, I dare say, anywhere else in the world. I say moralistic because it is linked to the relationship between creativity and the market (something considered improper and vaguely immoral), as if capital art did not live by the market, but only by air and intuition. The loss of the aura described by Walter Benjamin goes back to the 1930s, and also refers to the relationship between art and photography, art and film, precisely because of that reproducibility of the mechanical medium and the viewer’s perception compared to, say, a painting on canvas. He died long before the emergence of explosive phenomena, such as Pop Art for example, which veered into unexpected routes and gave birth to a language in which the word pop can be extended to everything, just as for a film you can say “Fellini-like,” and we all understand what is meant.

But we had Leon Battista Alberti and his “categories,” and we have not reformed much from there. After all, the invention, in the 19th century, of Arts & Crafts was born in England by a brilliant William Morris together with his fellow travelers, the Pre-Raphaelites, who have been despised by us for a long time, considered “minor,” niche artists, as they say. Mr. Morris was thinking yes of an art that invested the cultural and social universe in all its declinations (as it was, though in a different way in the better-known Bauhaus in which there were also masters such as Kandinsky and Klee), but he was trying to counteract a development of industrialization launched toward goals of economic and productive leveling, as we know, to widen the market to the demand of the masses.

Of course, the concept of design was still in its infancy, and craftsmanship was the experience that survived the growing bulimia of assembly lines in factories. But if design means project, then things and phenomena need to be viewed differently, more broadly, and more cross-culturally.

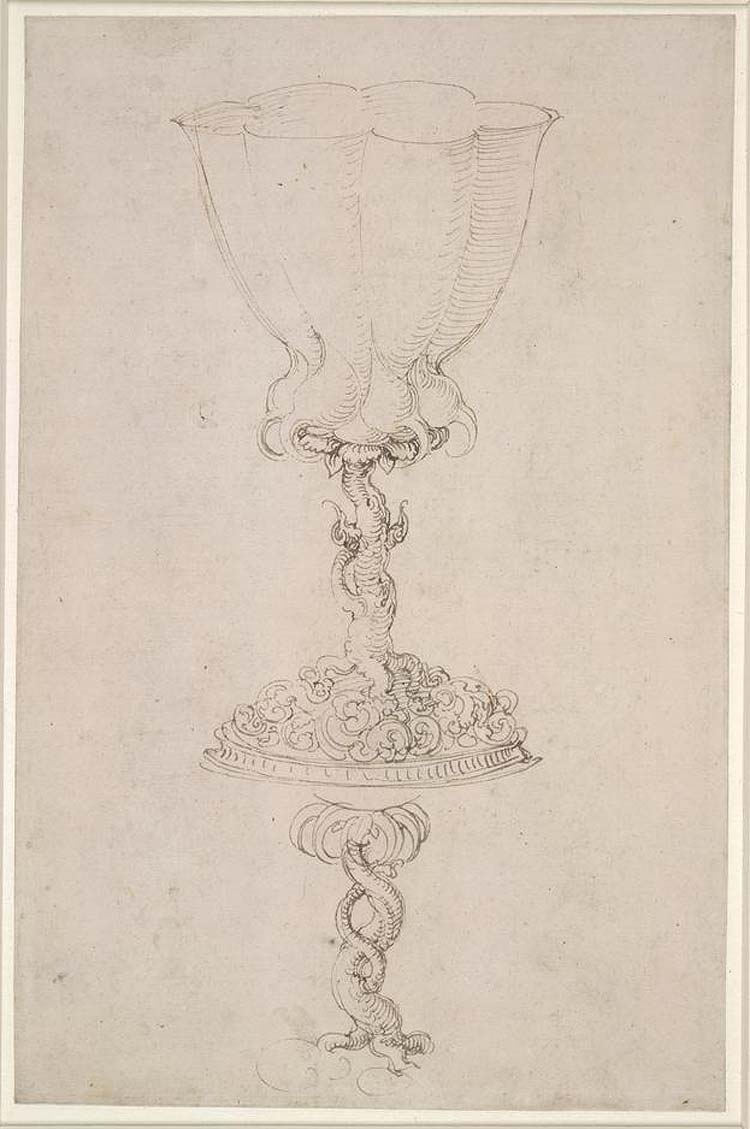

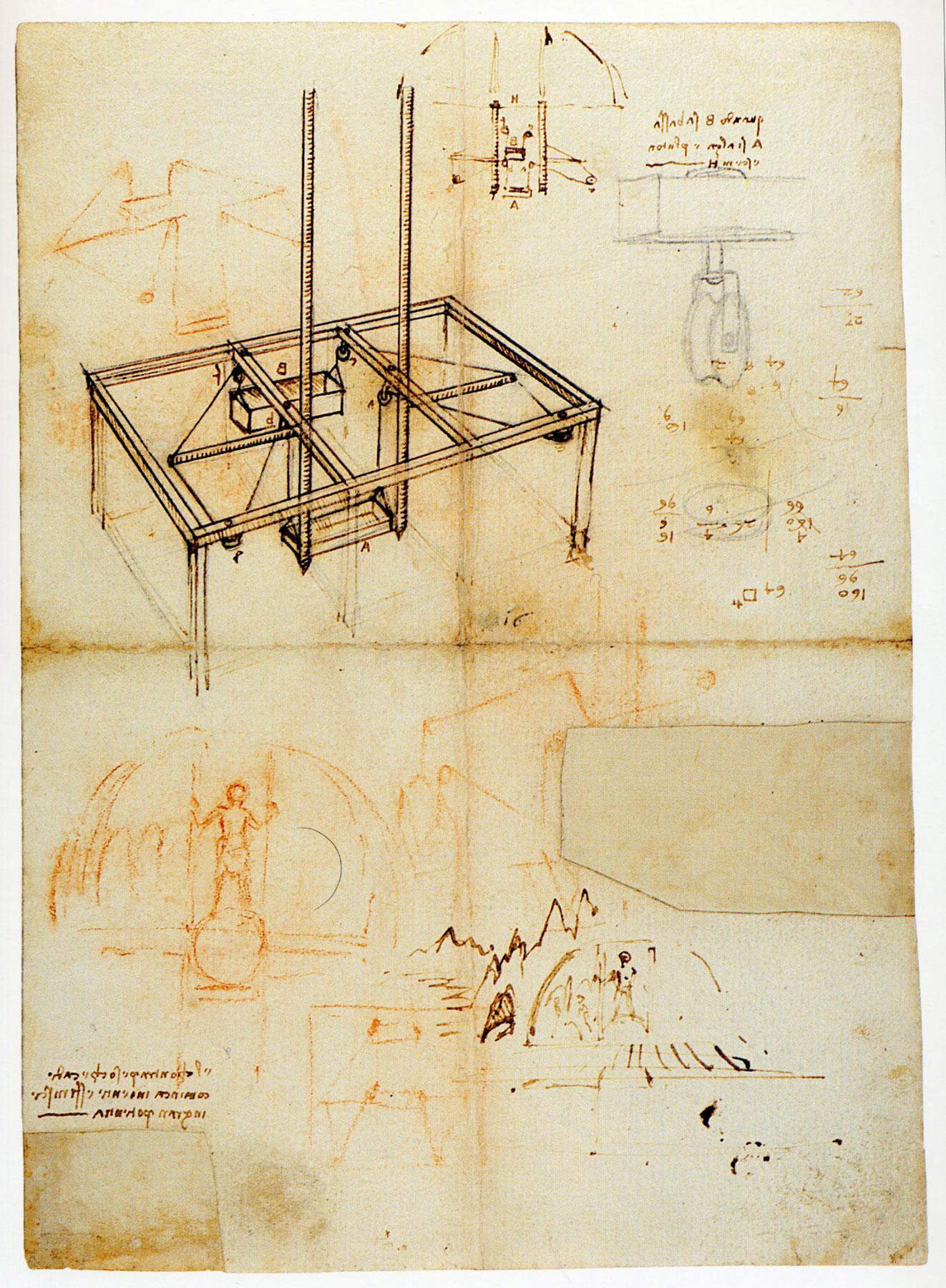

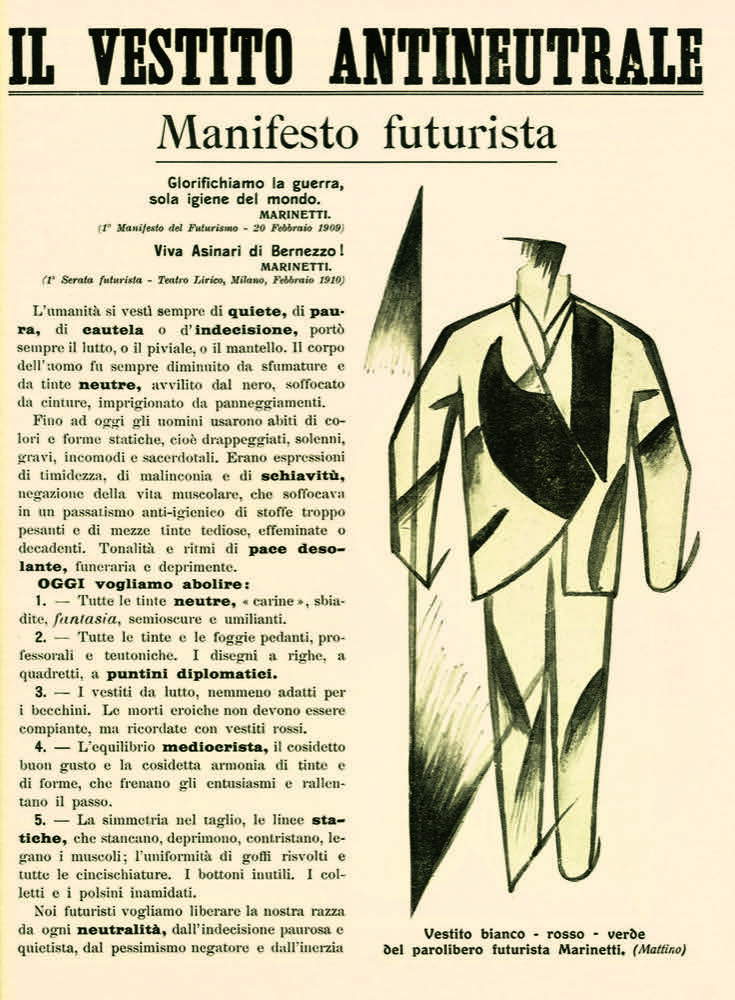

Artists have always given life to their own designs, made “serial” engravings in their own right, and it seems that Dürer had also created jewelry, not to mention Leonardo, as far as organizing themed parties for the King of France was concerned, and we cannot fail to mention, much later, Mr. and Mrs. Delaunay, and especially Sonya, “designer of paintings, wallpapers and dresses.” Speaking of clothes, I am reminded of the collaboration of Elsa Schiaparelli, Coco Chanel’s rival, with Salvador Dalí and Jean Cocteau. In short, I want to say that artists are artists, and the more experimental ones have become freely curious about different techniques and artifacts in the name of design and freedom of thought. The art/life binomial is not the heritage of research in the 1960s, but goes back much earlier and refers to cultural, social, political values in a general sense. Isn’t the ideology of Futurism one that embraces everyone and everything and declares its avant-garde thought even in an Antineutral Dress designed by Giacomo Balla, the painter? Is it not true that Fortunato Depero, in addition to painting, had created screens, toys, chairs, precisely in the name of that utopian idea of a total work of art?

Speaking of design, it must be said that a very young Bruno Munari approached the poetics of Futurism and then broke away and went down other paths such as that of the Concrete Art Movement, together with a Gillo Dorfles who, then, in turn, would be celebrated art critic at the international level. Bruno Munari is the one who best embodies the eclectic spirit that makes him a designer perfectly integrated with the world of industrial production, but he is also the one who gives life to the Useless Machines, and he is always the one who addresses the world of children by creating the prelibri with the advice of Gianni Rodari.

Today design is also interior design, land design, light design, dressing design, graphic design, urban design and much more. Artists have looked to design and designers have exhaled to art, each according to their own air of the time.

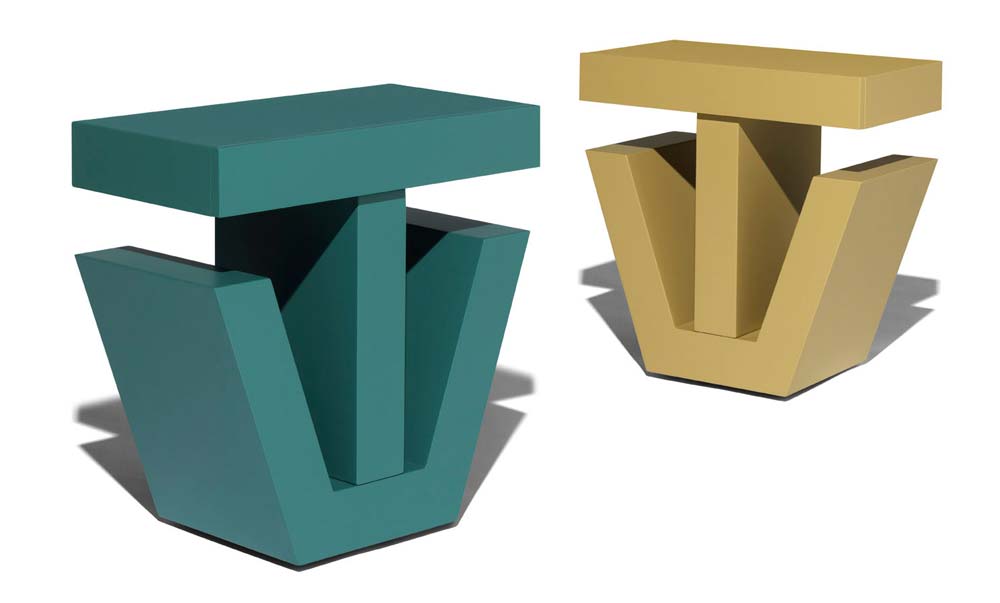

The two families remain minimal and pop research and have alternated over the decades while, today, they coexist in the globalized world without bothering each other, so Bolidism has in the figure of Massimo Iosa Ghini, a designer-architect who was ideally born from an affinity with Futurism, as he himself declares, and Gufram continues to produce the sofa Bocca by Studio 65, created in the early 1970s, inspired by Savador Dali’s portrait of Mae West ( who should be remembered not only as a painter, but also as a sculptor, filmmaker, screenwriter, writer, photographer, and designer) who, for his part, had made surreal objects and furnishings from Mae West’s own Room such as the Lobster Phone.

![Meret Oppenheim, Tavolino traccia (1938-1939 [1972-1984]; legno dorato e bronzo, 63,8 x 68 x 53,2 cm; Londra, Victoria and Albert Museum) Meret Oppenheim, Tavolino traccia (1938-1939 [1972-1984]; legno dorato e bronzo, 63,8 x 68 x 53,2 cm; Londra, Victoria and Albert Museum)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2023/2259/meret-oppenheim-tavolino-traccia.jpg)

The

The

Another artist-artist, Meret Oppenheim, in 1939, had designed the Traccia Coffee Table, with legs made in the shape of bird’s feet, reissued in the 1970s for the Ultramobile collection commissioned by Bologna entrepreneur Dino Gavina. One of the most significant minimal artists Donald Judd inspired many designers including Ron Arad and his Bookworms of the 1990s, not to mention Stefano Giannoni’s 1990 TV cabinet that looked to theunmistakable icon-logo of Robert Indiana, Love, from the 1960s, as well as Tejo Remy, with his Rag Chair, which denounces an obvious affinity with Michelangelo Pistoletto’s Venus of Rags , and recycles natural materials in the name of sustainable design. In this sense, one cannot help but compare Jurgen Bey’s 1999 Tree - Trunk - Bench with some of Giuseppe Penone’s works. After all, the celebrated Ingo Maurer for his System Ya Ya Ho is a clear reference to Calder and his suspended sculptures.

With the pop use of plastic, or rather plastics, here pop up Gino Marotta’s installations and Carla Accardi’s Sicofoils. New York’s MOMA, temple of modern and contemporary art, welcomed, in 1972, the first exhibition on Italian design, entitled Italy, The New Domestic Landscape. The museum, a pioneer in this, has its own section devoted to design.

The manifesto of what I have exhibited so far remains Gerrit Rietveld’s chair that pays homage to Piet Mondrian, in 1921, that same Mondrian who becomes a motif in a famous dress created by Yves Saint Laurent, fashion designer and art collector.

There are some figures, more complex than others, in the art world, Yayoi Kusama and her universe of polka dots, interactive polka dots and polka dots featured in Louis Vuitton’s latest ad campaign. Provocatively I ask: Is Kusama an artist-artist, interior designer, fashion brand? Artist period.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.